A video game script is a written document containing all the spoken lines of a video game. Dialogue, audio recordings, player character narration, cutscenes, and contextual information to help actors and directors are included. Write a video game script by combining classical elements of storytelling such as character, drama, tension, and narrative payoff, with the interactivity and player agency that games require.

Video games differ from other media in that the player determines the outcome. This determination boils down to binary play-or-fail choice in bullet hell shooters to complex, branching narrative choices in story-heavy RPGs. Game scripts aren’t always produced before the gameplay. The role of the game writer is to create narrative reasons for set pieces and gameplay events already created by the team. Effective game scripts involve understanding the game’s core loop, researching its theme, building its game world, and more. Read on to learn how to write a script for a video game and how the practice differs from other media.

1. Understand the core gameplay loop

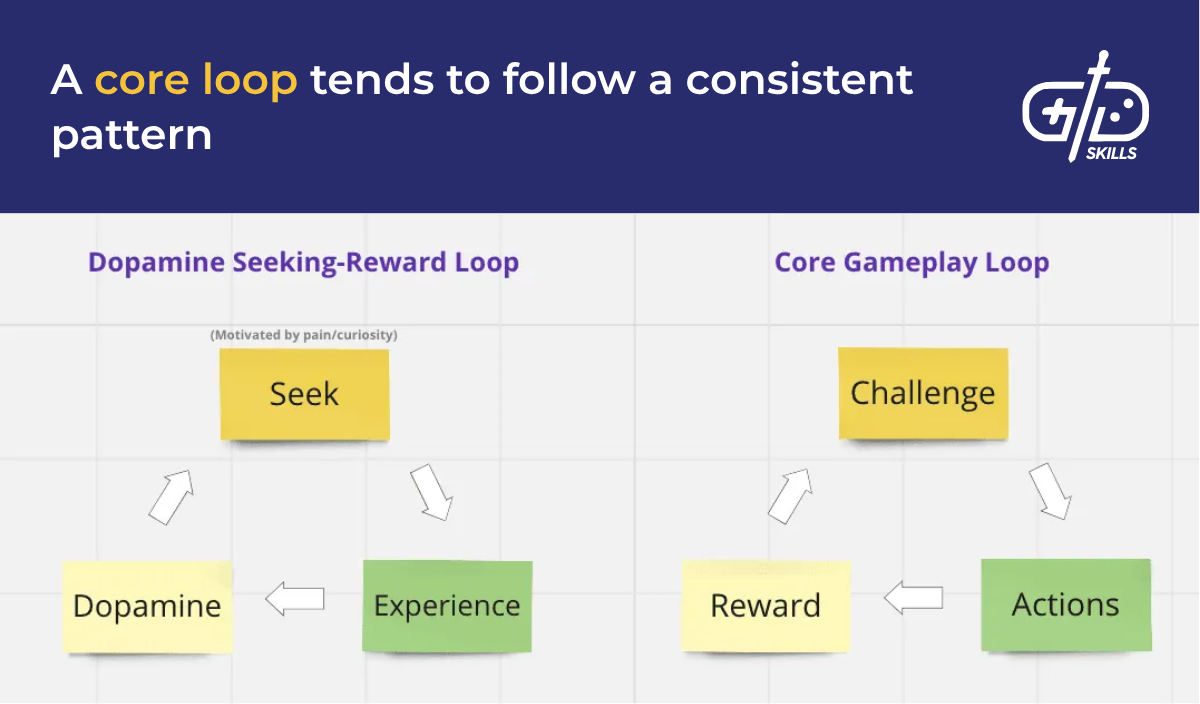

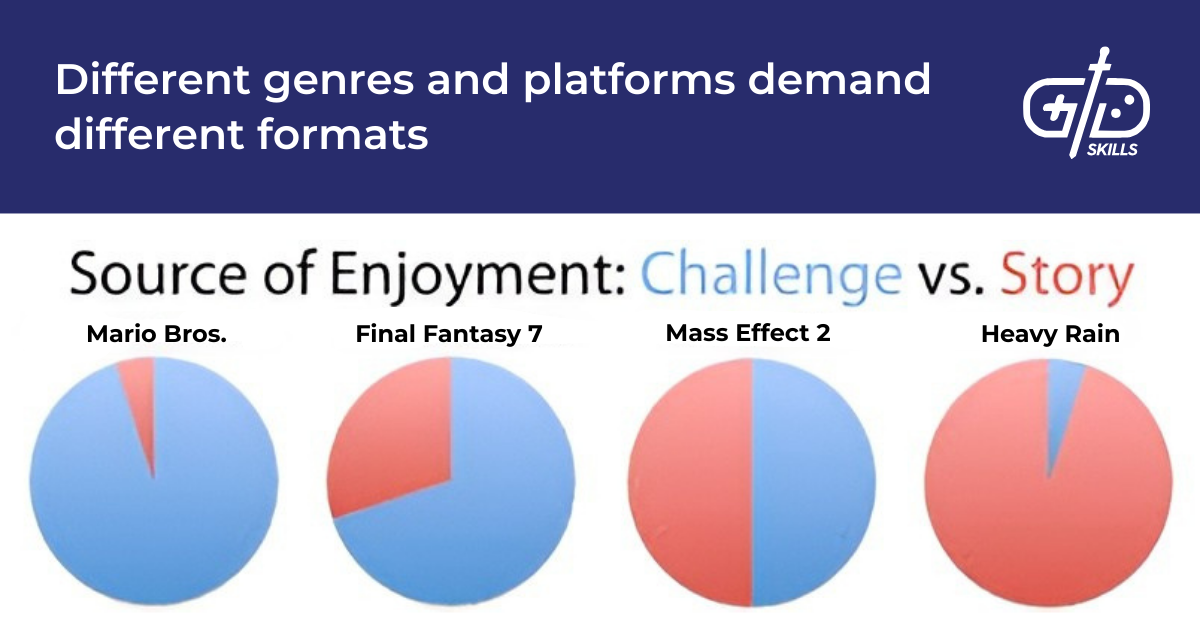

Understanding a game’s core gameplay loop helps to determine what type of script best serves the project. A game’s core loop is the series of actions that represent the bulk of the gameplay. Different core loops create different genres which, in turn, demand different script formats. The purpose of a game’s dialogue is to connect the game’s core gameplay loop to the emotions and motivations of its characters and plot. Different gameplay loops place specific demands on dialogue.

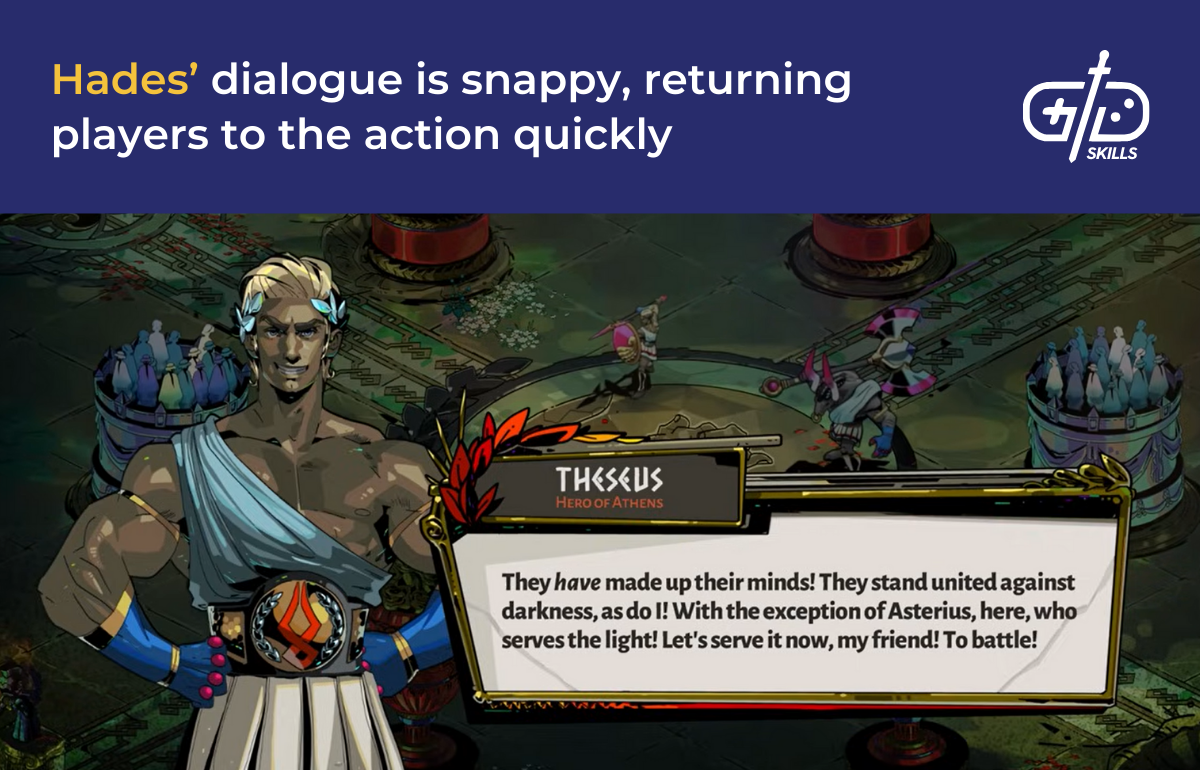

Take the roguelike genre as an example. Roguelikes follow a talk → fight → loot → upgrade → talk loop, where the player experiences short bursts of dialogue to tell them where to go and who to fight, before pursuing the quest through combat then returning to the quest giver. This format demands snappy dialogue that sets up gameplay quickly. A more narrative-focused RPG uses deeper, slower-burning dialogue and a less rigidly structured loop. An open-world RPG might include scripted moments along the way, longer character arcs, moments of environmental storytelling, and dialogue with branching choices.

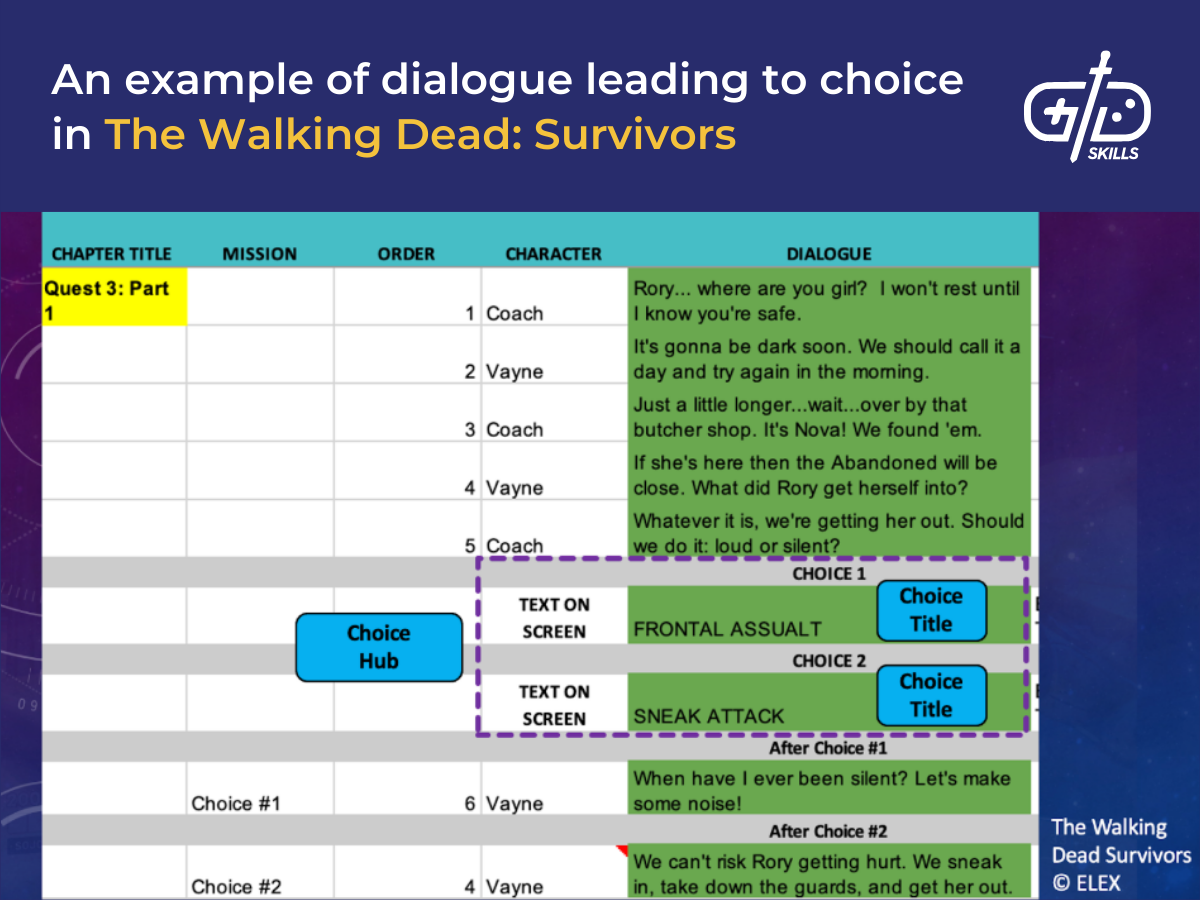

The Walking Dead: Survivors, for example, uses dialogue to set up quests, but also to introduce the elements of a new gameplay mode. When I created the scripts for situations preceding a new gameplay element, I had to ensure the player was clear on what’s new and how it affects gameplay. The airhorn (used to attract zombies or draw them away) had to be explained through dialogue before the player engages with the mechanic, for example. Dialogue in video games isn’t just about plot exposition. Writers must also explain mechanics, signpost objectives, and connect gameplay to the characters’ motivations and emotions.

2. Research the theme to determine the story

Research the theme to determine the appropriate style, tone, and story arc. The plot is what happens in a story, the theme is what that story says. A video game’s theme is the underlying message that its story explores through narrative, characters, tone, and gameplay. Research is important to ensure the theme is reflected in the writing. Cyberpunk 2077’s theme is (in my opinion) – What does it mean to be human in a world of rampant inequality, virtual reality, and cybernetic modification?

Cyberpunk’s theme of human identity in a world of technological intervention, corporate wealth, and widespread, relative poverty suggest a specific style of writing and dialogue. Players expect the NPCs of a gameworld like Cyberpunk’s to be streetwise, cynical, and slow to trust. The expectations for story and character arcs in this style of game require the writing to highlight the human effects of blurring the line between man/machine and reality/the virtual.

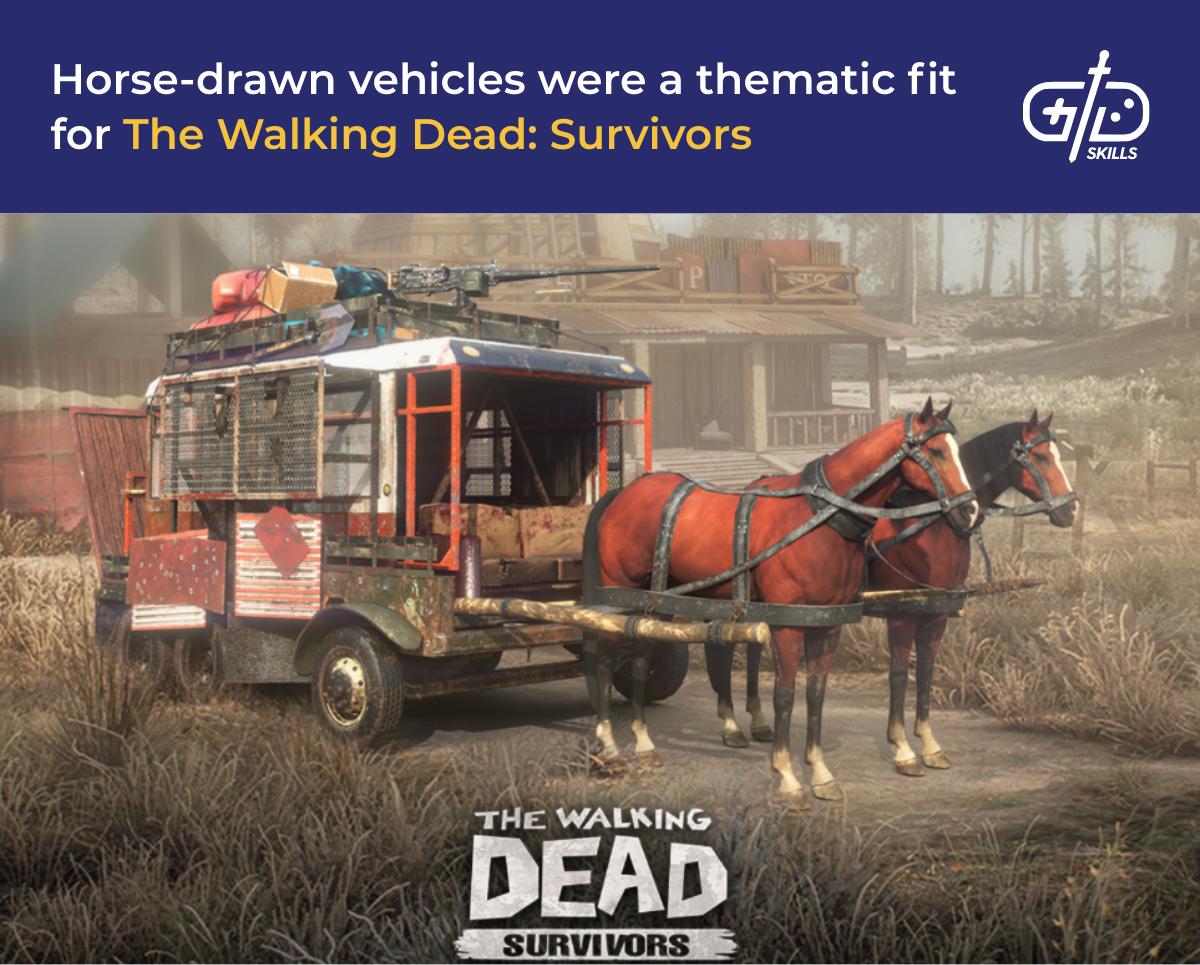

Themes are the impressions art leaves after specifics fade. This concept is important in video game writing because games are beloved for the feelings they give us, and rarely for the stories they tell. Great plots, characters, factions, and quests are crucial elements of effective video games, but must serve the power fantasy inherent in the game’s promise. IPs have brand bibles that help writing teams stick within parameters. When it came to The Walking Dead’s vehicle system, I knew that gasoline was scarce and our team had to design alternate “propulsion” methods. After researching the brand, I designed a storyline where the player could use modified vehicles that were pulled by horses (of varying sizes and types), and that was approved by SKYBOUND ENT. (the IP holder).

3. Build the game world to connect the story to its features

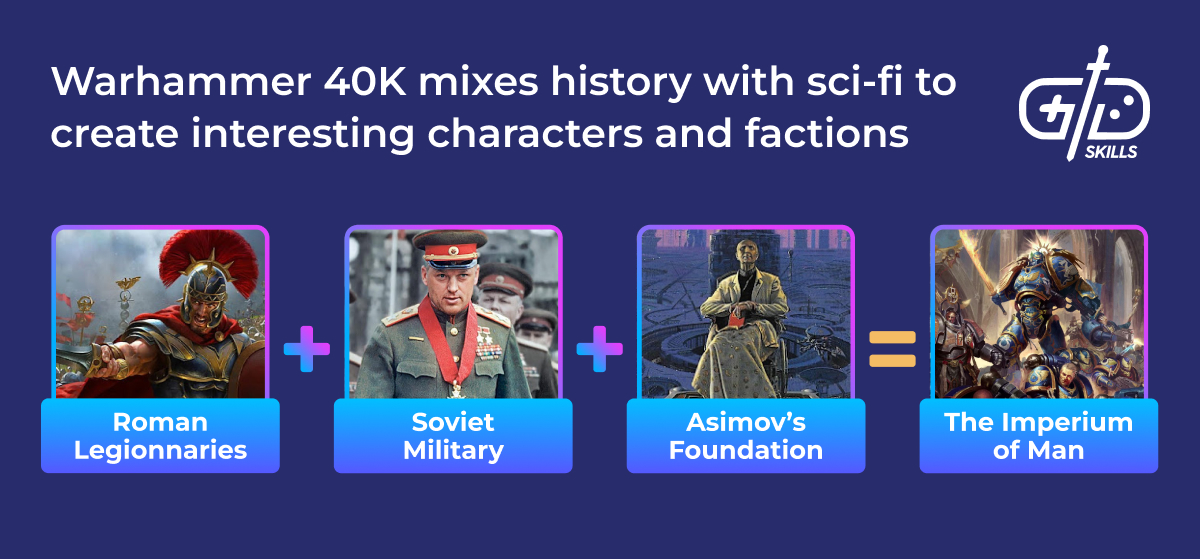

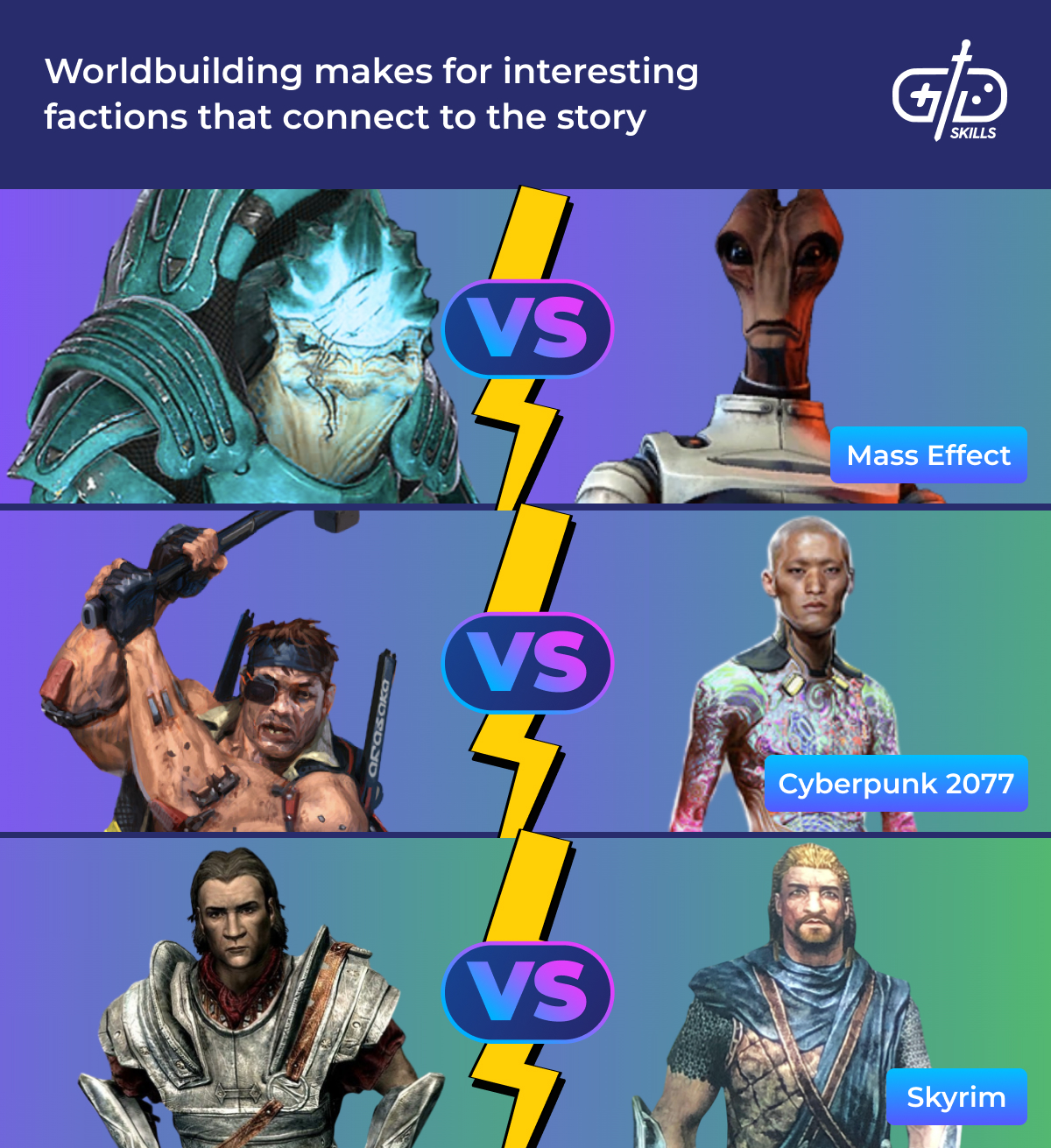

Building the game world means creating the factions, biomes, creatures, levels of technology, and a simple map. Creating these elements before writing the dialogues means the story doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and characters have coherent loyalties, motivations, and backgrounds. Stories are about people, conflict, resources, and ideological differences. Building a game world distils these elements, inspiring ideas for quests, relationships, and dialogues.

Conflicting factions are a cornerstone of video game worlds and their stories. Stormcloak versus Imperial, Nilfgaardian versus Redanian, or Krogan versus Salarian – video games connect their personal stories to wider struggles in the game’s fiction. Thematic factions give writers room to explore ideas that fit the tone. Take Cyberpunk 2077 as an example. The story expectations for its gameworld are built around factions like supranational corporations, streetpunk-inspired, cybernetically modified gangs, luddite, anti-technology factions, and cults that blend the technological with the mystical. The player expects complex moral choices with few clear-cut good guys or bad guys.

Build biomes that reflect the tone of the story at the point when the player encounters them. Effective games use a change of location to underline a shift in narrative, tone, or the parameters of gameplay. The famous Bethesda RPG the rails are off and the world is open moment is an example of a shift in location and gameplay options. Different locations and factions typically have different levels of technology. The technologically superior force versus the more ideologically committed inferior force is a classic trope. Use a map to keep track of where the factions are and what zones they threaten. Simple, effective map makers are available for free (with optional paid features) from Inkarnate, Wonderdraft, and Dungeondraft.

4. Design character profiles to create new characters

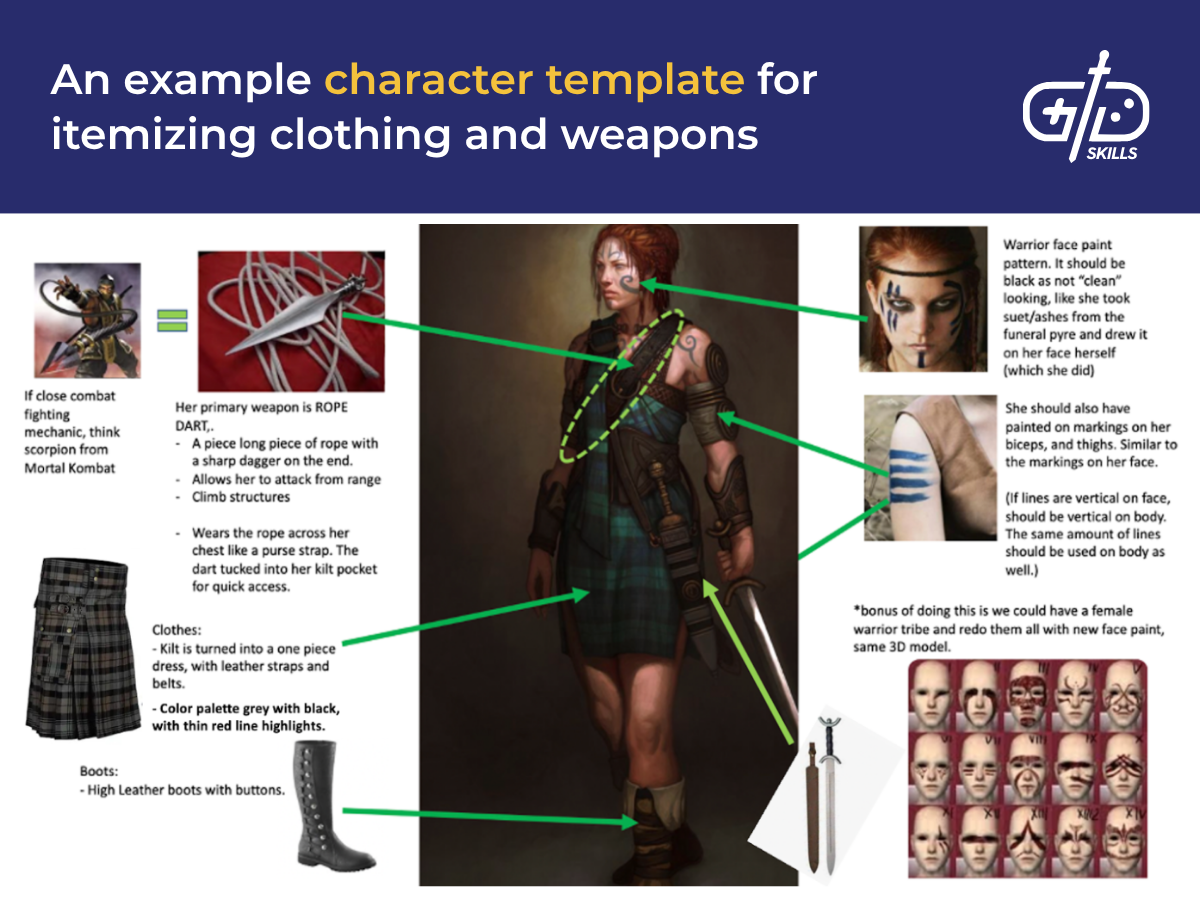

Design character profiles to fill your game world with memorable, individual visual styles and personalities. Start with the most striking visual and personality elements and work down. Use a template to detail each character’s face and head, torso, arms, legs, and footwear. A 3-line backstory for every named character is enough to transmit character archetype, loyalties, and motivation. Consider a list of data points for each character entry depending on genre. Typical examples are age, gender, personality, occupation, and faction.

When creating characters’ visual designs, using reference material from other media is an effective way to transmit details. Don’t depend on any single licensed image. Swap and alter features and colors by referencing multiple images to create something unique. Depending on the genre conventions, include a second copy of the template to cover weapons and attacks. The goal is to create characters that fit the theme whose personalities are reflected in their aesthetic, clothing, gear, and attacks (if applicable).

The level of detail given to each character’s backstory is linked to how prominent they are in the plot. A suggested formula: named characters get a specified number of data points (age, gender, occupation, etc. ), and a maximum of 3 lines explaining their backstory as it relates to personality, loyalties, and motivations. More prominent NPCs, playable characters, and companions require more detailed notes. Remember, the ideal number of words is the fewest possible to transmit the information required. You want the rest of the dev team to read this stuff, so keep it brief.

5. Develop the main plot

Develop the main plot to determine the ultimate stakes that exist between the player character(s) and the antagonist(s). You’ve established a theme, built the game world, and designed characters to inhabit it – now you need a resource, person, or point of ideological conflict standing between those interests. The process boils down to determining who the conflict’s with, what the conflict’s over, how the player character fits in, and what’s ultimately at stake? Refer back to your game world notes and map to create a timeline of events that works for the game and genre expectations. Open-world RPGs, for example, typically feature self-contained faction and region quests with their own smaller-scale conflict resolutions. More linear experiences follow a single arc of conflict→ escalation→ resolution.

Antagonists are a cornerstone of effective video game plots. Game villains vary in their moral complexity and nuance according to genre and tone. The key is to make the bad guy(s) the antithesis of the player character, a plausible threat, and give them a coherent reason to stand in opposition to the player over a key issue. Resources, land, and political disputes are only as interesting as the characters behind them. Creating the main plot comes after creating characters for this reason. Not every game demands a complex plot. Our princess is in another castle is more than enough narrative alongside the fun challenge of Super Mario Bros.

With game plots, the higher you can make the stakes, the better. Not every game is about saving humanity from an existential threat, but every game is about potential loss and the value of action over inaction. Games are games because we play to win. Plots create an emotional reason to want that victory. On The Walking Dead: Survivors Season 2, I worked on the Queen of the Dead to introduce a new antagonist, Caroline Harper. The conflict was clear: she was using walkers to threaten settlements for protection money. The player’s role as a settlement leader creates a clear point of contention. The fun is in unravelling the plot and figuring out defensive techniques and ways to turn Caroline’s walkers against her.

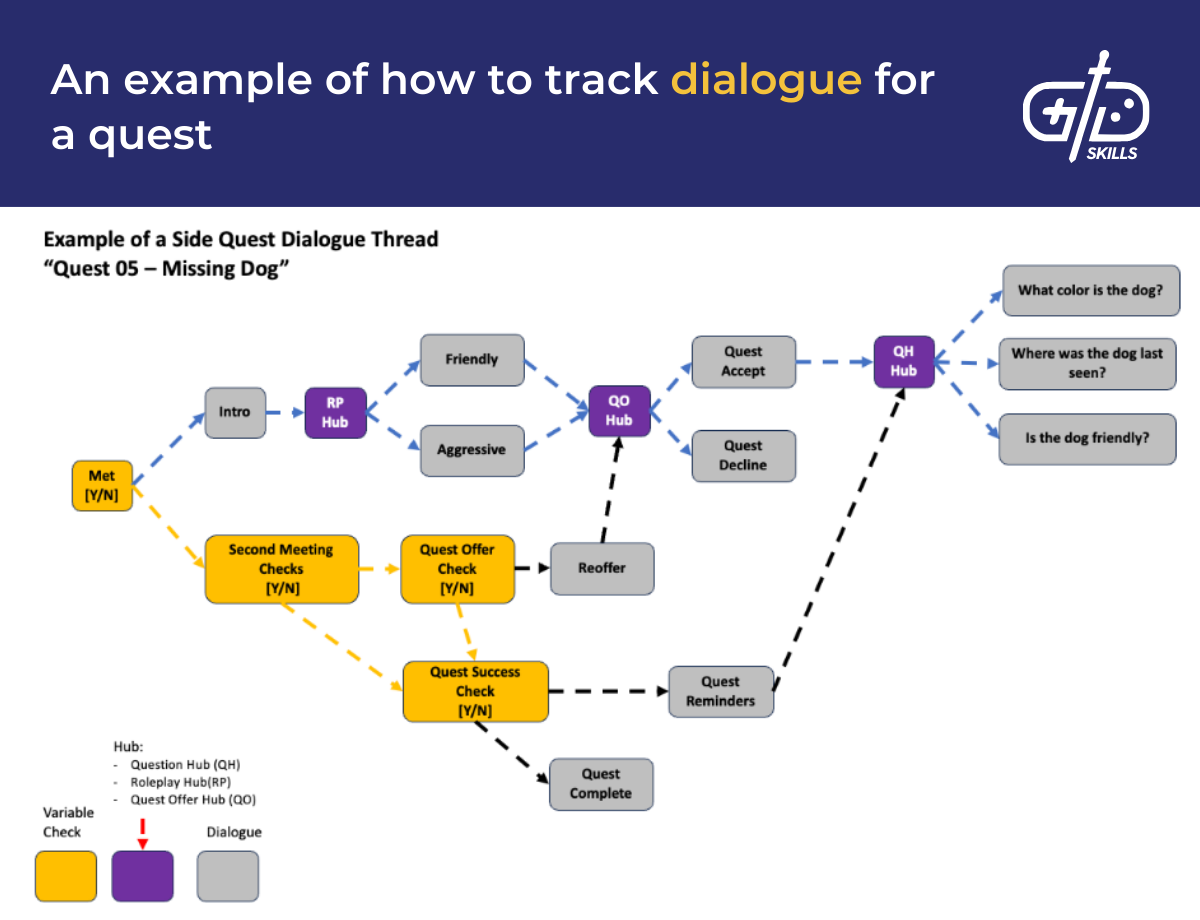

6. Design the narrative system

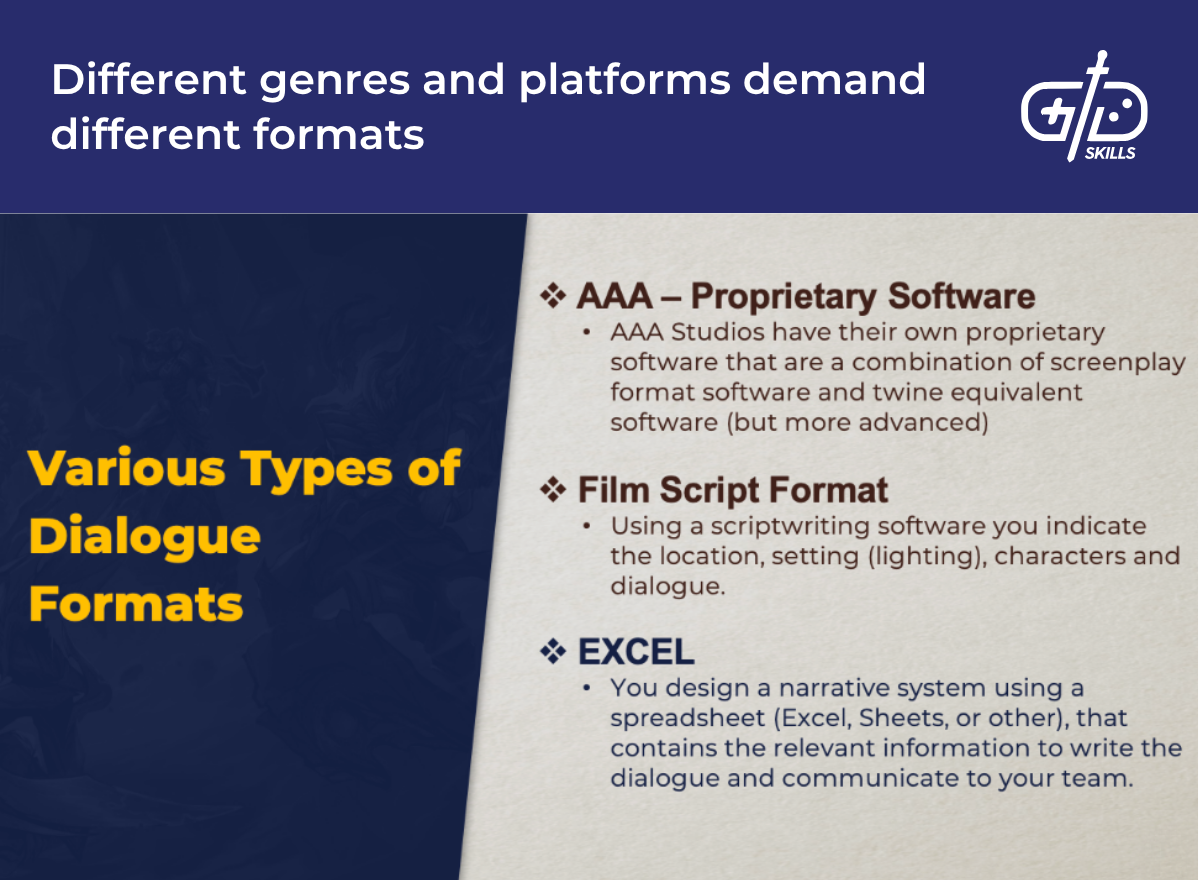

Design the narrative system to fit the genre, format, and unique needs of the project. Players of AAA, AA, indie, and mobile games have different expectations of dialogue systems according to the type of game. Branching dialogue for an RPG works differently to a linear puzzle game’s dialogue, and demands a different form of narrative system, as an example. A game’s narrative system determines how the story is structured, how it’s delivered, and what states are tracked by the game and its NPCs. Determining the goal of the narrative system helps determine the most effective fit.

The goal of the narrative system in an open-world RPG like Skyrim is to integrate a narrative into its open-ended gameplay. Skyrim features modular quest states that categorize quests into not started, active, and completed definitions. The game’s emergent world event system triggers ambient stories and encounters while exploring, and fits inactive quests around nearby settlements and NPCs in a modular system. An NPC state manager means the NPCs remember events and actions the player takes while core lore and story elements are revealed through notebooks and overheard conversations. Skyrim’s narrative system (like any game) is a series of trade-offs. The game’s freedom is part of the fun but limits the game’s ability to tell a strong, traditional story.

Dialogue and narrative systems introduce the crisis behind a quest, direct us towards its resolution, and then back to the quest giver for reward. The design philosophy of the game determines how this works. On Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, the remit was to work with designers on an area of the map, creating quests to fit. The Arkalochori Axe sidequest is one example. The object existed before the quest. (The real one is at the Heraklion Museum.) The player learns that the axe is required by a priestess for a ritual, demanded by the local overlord, Swordfish (who happens to be standing in our way). Bandits have stolen the item, however. Once the player returns from the combat/stealth mission with the axe, they learn the next step in tracking down the overlord.

7. Draft dialogues

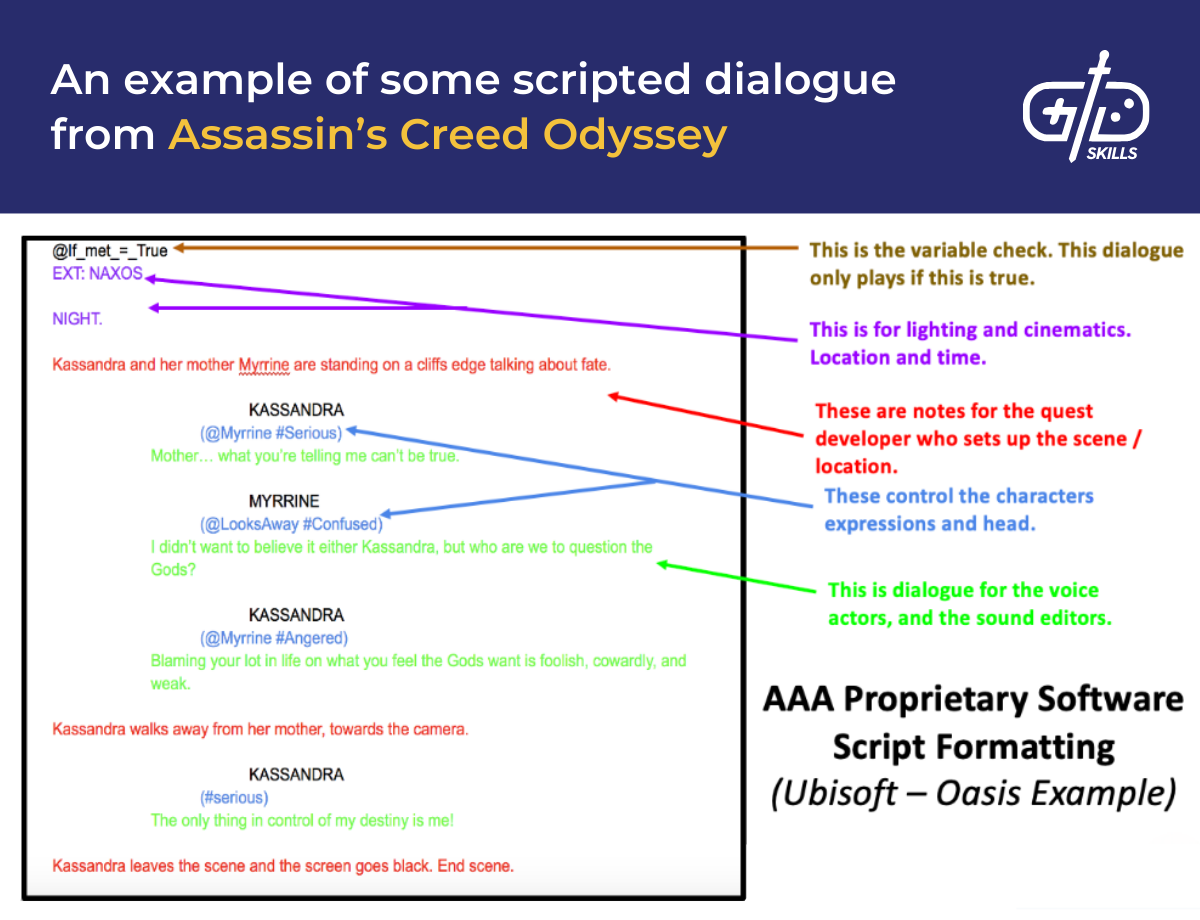

Draft the dialogue scripts once you’ve established the plot and narrative system. The types of dialogue in video games are grouped into the categories linear, branching, hub and spoke, environmental, barks, and ambient. Linear dialogues progress in response to a button press, branching dialogues take players down a specific path based on choice, and hub and spoke systems return players to a central topic hub. Environmental and ambient dialogues are location-based speech from radios, audio logs, or NPCs. Barks are the lines player characters, companions, and NPCs reuse in appropriate repeated situations (eg. after a battle, on drinking a potion, or when in need of healing). Each type of dialogue requires a different approach and format.

Once a draft is written – write a second to check over. Remember dialogue fulfils several functions in video games – plot exposition and player guidance, characterization, tone-setting, and emotion, and facilitating player agency and choice. Include only dialogue that steers players, builds characters and tone, or offers players choice and agency. After you’re happy with a draft, submit it to the producer/lead director. (If a licensed IP, the holder has veto and will check at this point.) Iterate on feedback from your producer/lead to improve before having the team play the level/section. Use their feedback to add tutorial text barks or leading player character dialogue in sections where the objectives, systems, or mechanics are unclear.

Remembering that the player is the center of a game’s action is important when writing dialogue for video games. Scripts for non-interactive visual media allow for the protagonist to react to what other characters in the film/TV/play are doing. Video games must keep the player at the center, largely depending on NPCs to react to player action, and not the other way around. A similar principle applies to world building through dialogue. World building dialogue feels unnatural when it forgets the “what’s in it for me?” principle. Connect world building to what the player is doing and avoid the kind of lore dumping that leads to players skipping dialogue.

8. Write cutscenes

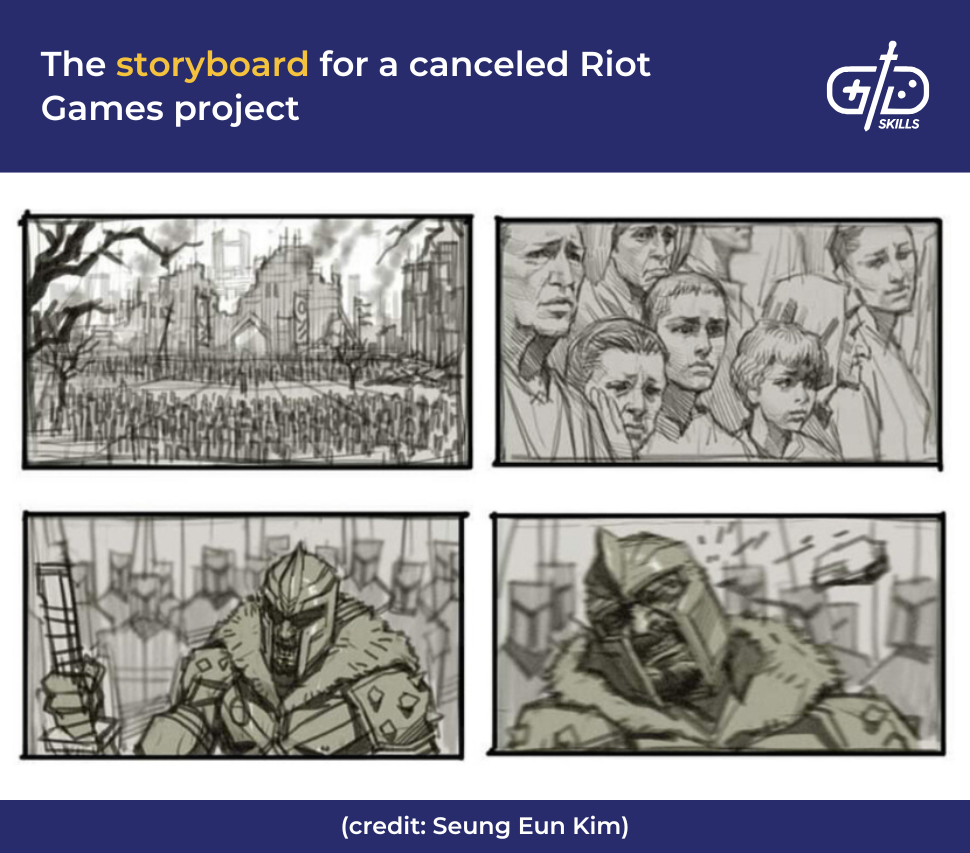

Write cutscenes by brainstorming scripts that stick within the project’s scope and budget. For game cutscenes, scope and budget determine the number of characters, art assets, and effects of both in-game and outsourced 3D model clips. Once the content is approved by your producer/lead, the finalized script is entered as a PowerPoint presentation, Excel Doc, or any other production tracking system the team uses.

The team creates a stick figure storyboard to confirm pacing, framing, flow, and number of shots. Once everyone is happy with this version, submit it to the IP holder for review (if applicable). The idea is to avoid spending time and resources on something that won’t make the final cut. An official storyboard comes next, giving more detail on composition, movement, and framing. Once this storyboard is complete, an animatic is produced. An animatic is a pre-production video that acts as an animated storyboard with sound and primitive effects. Once the animatic is approved and iterated upon, the final cinematic begins to be crafted.

Cutscenes are an important part of the players’ journey where some autonomy is sacrificed for narrative and cinematic purposes. Use cutscenes to introduce characters or locations, build tension, introduce gameplay set pieces, or act as payoff for completing gameplay challenges. Game cutscenes fall broadly into one of 3 categories: completely cinematic (Final Fantasy series) interactive cinematic (Mass Effect), in-engine cinematic (camera takes control seamlessly like in God Of War), or environmental cinematics like Dark Souls where player POV doesn’t break.

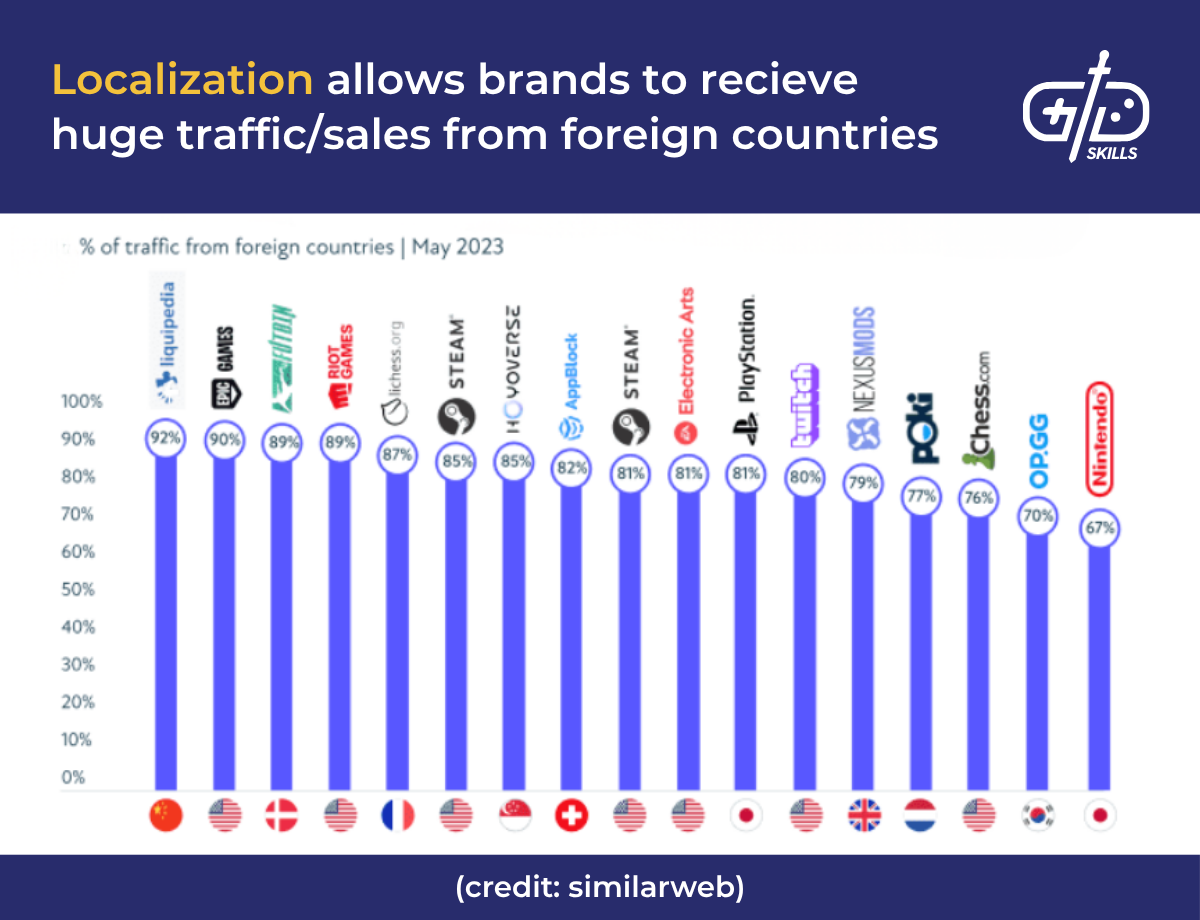

9. Design localization document

Design the localization document once all elements of the script are finalized. A localization document is a structured guide that ensures the game, and all related content, can be seamlessly translated into multiple languages. A localization document includes all in-game text along with essential context and notes on technical constraints. An overview, style guide, and glossary are core components of the document that help translators retain the spirit of the original script and writing. The large volume of international sales makes localization an essential step for studios of every size.

All in-game text and dialogue must be included in the localization document. This dialogue must be accompanied by relevant context such as who is speaking, where the dialogue is happening, and any other background information pertinent to the scene. It’s important to include UI constraints like character limits or space limitations in this section of the document. Different languages may require a different number of characters to achieve the same meaning and hard parameters avoid confusion.

An overview, style guide, and glossary help with clarity of tone, theme, and intention across multiple translations. The overview must give a succinct but tonally coherent synopsis of the game’s setting and central conflict. The style guide helps to guide translators identify the target audience, maintain the intended atmosphere, and outlines the preferred writing style and tone. The glossary section includes key characters, terms, items, factions, and other crucial terminology to the game world. Gaming’s many sci-fi and fantasy naming conventions mean an easy to understand glossary is essential for effective localization.

10. Design voiceover actor document

Design the voiceover (VO) actor document to give the actors all the spoken lines, standardize pronunciation, give context like emotion, tone, and pacing, and detail technical guidelines. The purpose of a VO document is to help the actors deliver consistent performances that match the theme and tone of the game. The document gives the actors background details that help them frame their performances in the broader narrative. The capture booth of a recording studio isn’t an especially inspiring place. A good VO document helps to inspire by mentally placing the actors in their scenes.

The character profiles in a VO document contain personality traits, relationship information, motivations, and background details like occupation or special training. Many VO documents contain pre-recorded sample lines to give actors an idea of accent and delivery. The details in the character profiles help the actors to interpret the scene details through their characters’ eyes, increasing the emotional authenticity of the performances. Authentic performances are further encouraged by notes on where dialogues are taking place, what the context is, and what the current relationship is between the speakers present.

Technical and performance guidelines in a VO document include notes on pronunciation, pacing, standard volume levels, file formatting, and naming conventions. The pronunciation and pacing guidelines help with maintaining consistent performances across multiple sessions and actors. Details on volume levels, compression rates, and the type of microphones used helps maintain consistent sounding voice capture, even when working across multiple continents. The file naming conventions help teams keep shared workspaces tidy and allow for easy cataloguing and searching.

How long does it take to write a game script?

The length of time it takes to write a game script depends on the scope and genre of the project, the amount of dialogue expected, and the level of complexity and branching options. The script for a retro or side-scrolling shooter potentially takes an afternoon to come up with a protagonist, antagonist, and some fun verbal sparring between the two to set up action. These kinds of twitchy games are primarily enjoyed for their challenge and player expectations for detailed plot and dialogue are low. RPGs, adventure games, immersive sims, and others come with expectations of more detailed characters, dialogues, and plots.

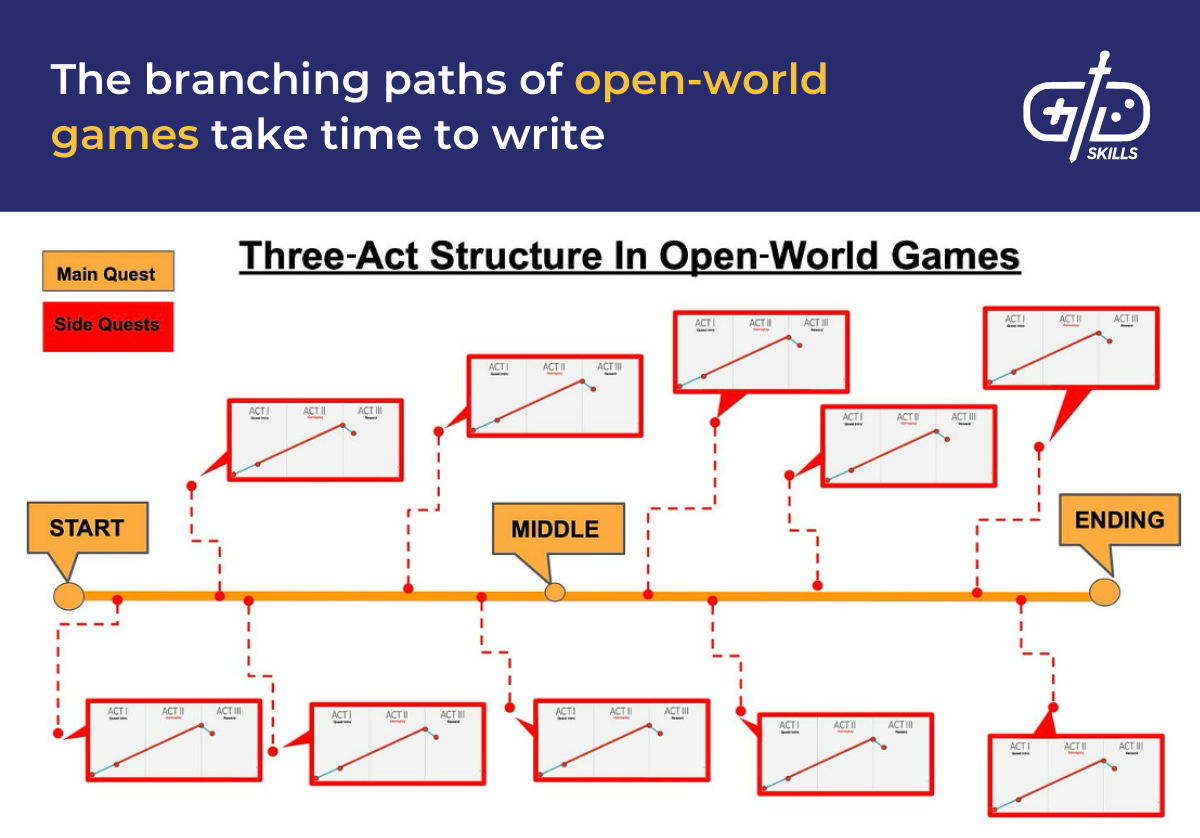

Games that feature branching paths in dialogue and plot take significant time and effort to write because the writing must support multiple outcomes without overstretching plausibility. Similarly, open world games must support ways for players to pick up and complete (many) quests in any order without breaking the game. It’s also worth mentioning that writers often continue to work after production has begun. When I worked on Age of Mythology Retold, I created dialogues and scenarios around cutscenes and conflicts the dev team had already created.

What is the best software for writing game scripts?

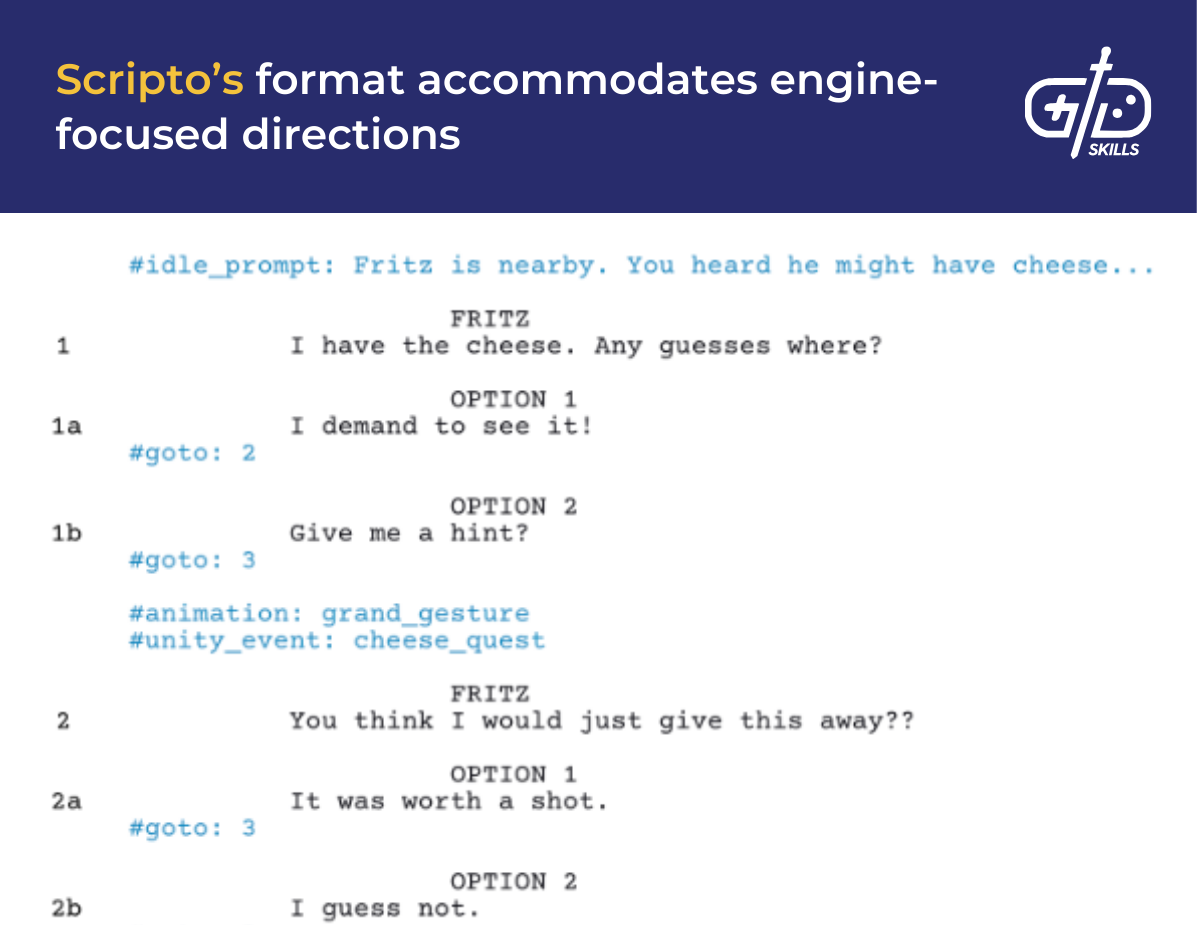

The best script writing software depends on team size, engine integration requirements, and workflow preference. For smaller teams who don’t require engine integration, non-game script-specific options like Excel or PowerPoint are relatively simple to use and allow for detailed contextual notes. Script writing software like Twine allows users to create fully interactive fiction experiences with branching paths and choices. Twine is useful for prototyping game scripts as well as standalone projects.

Celtx is an inexpensive, dedicated piece of scriptwriting software featuring a game friendly format with options for branching dialogues, hub-and-spoke nodes, and story-map visualization options to track events. Celtx suits writers looking for something more game-specific than general scriptwriting software. Scripto is an inexpensive (with limited free plan) scriptwriting software with API integration so writers and developers stay connected inside the game engine. Scripto is the best option for those requiring integration between the writing and production teams.