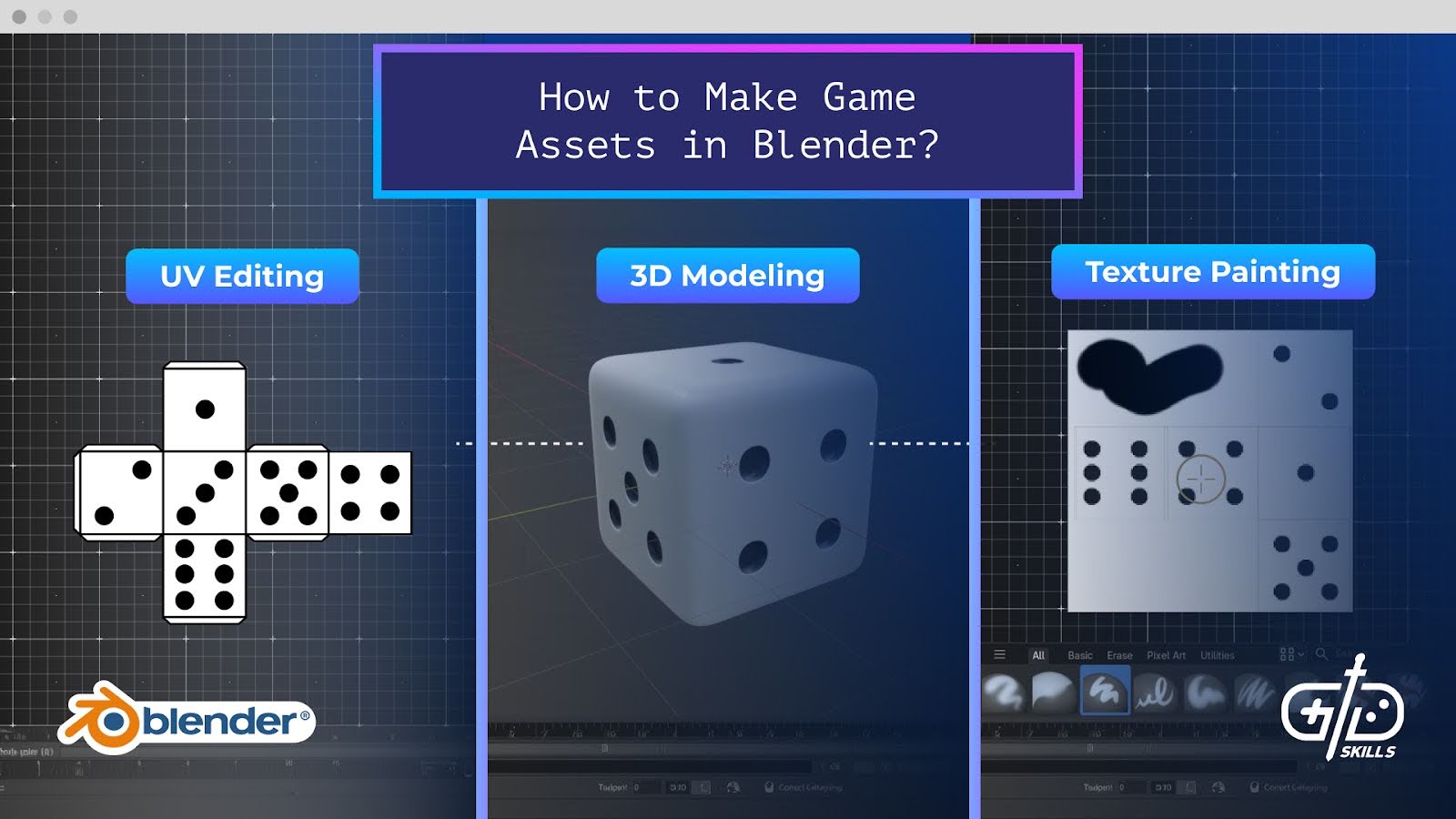

Making game assets in Blender has become popular as Blender has slowly improved the software’s 3D modeling, sculpting, and texturing workflows. Many artists in the industry, including myself, continue to use paid software like Maya and Zbrush, but the methods are similar across all 3D software, just with changes to the UI/UX. Learn how to make game-ready assets in Blender by understanding the process of blocking out, modeling, retopologizing, unwrapping, texturing, and exporting your work.

I’ve been working as a 3D artist in the industry for 5 years on over 40 titles. I’ve researched the implementation of the workflow in Blender, and I’ll share with you how a model goes from initial concept to 3D model to game-ready asset. Read on for a brief tutorial for Blender’s game asset workflow that’s accessible even to users new to Blender and game art.

1. Gather example images and concept art

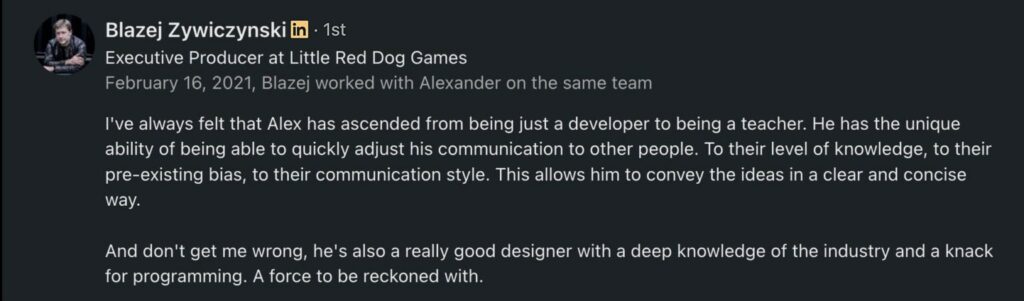

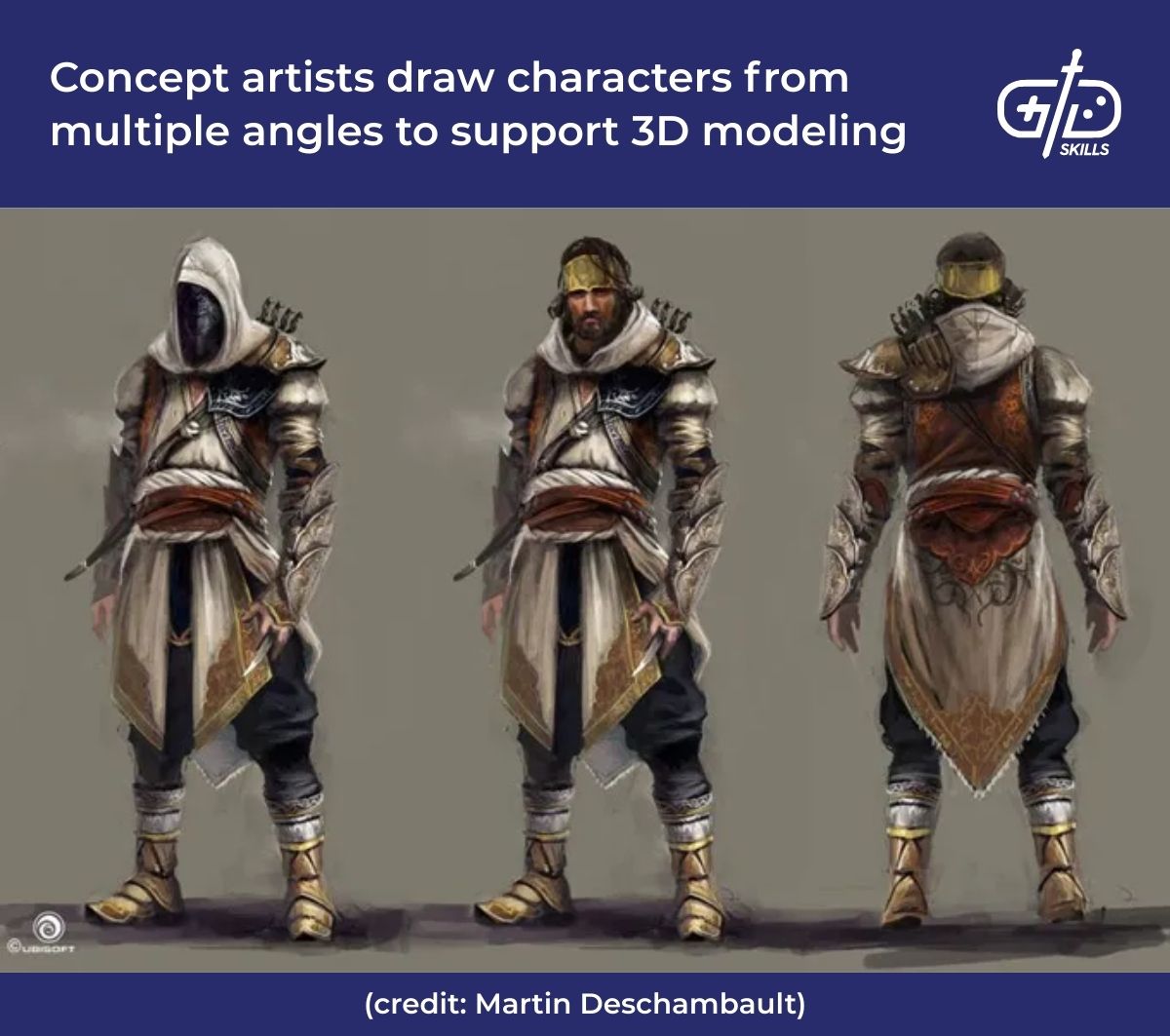

Gather example images and concept art to supplement the designer’s vision with as much detail as necessary. The designers and concept artists have already worked together to create references for you in a studio, so gathering references involves finding inspiration for the small details or getting references from other games to emulate their style.

The concept artist works with the design team and leadership to make sure the 3D artist has everything required to match the game’s needs. Concept artists usually start in 2D, although they have the option to block out in 3D for projects in smaller studios with less manpower. The concept covers the asset from different angles and in different states. A character, for example, needs to appear in multiple poses so the modeler is able to create something which bends, twists, and poses the way the designers want it to. This is another reason why consistent communication between designers, the concept artists, and the modelers is crucial.

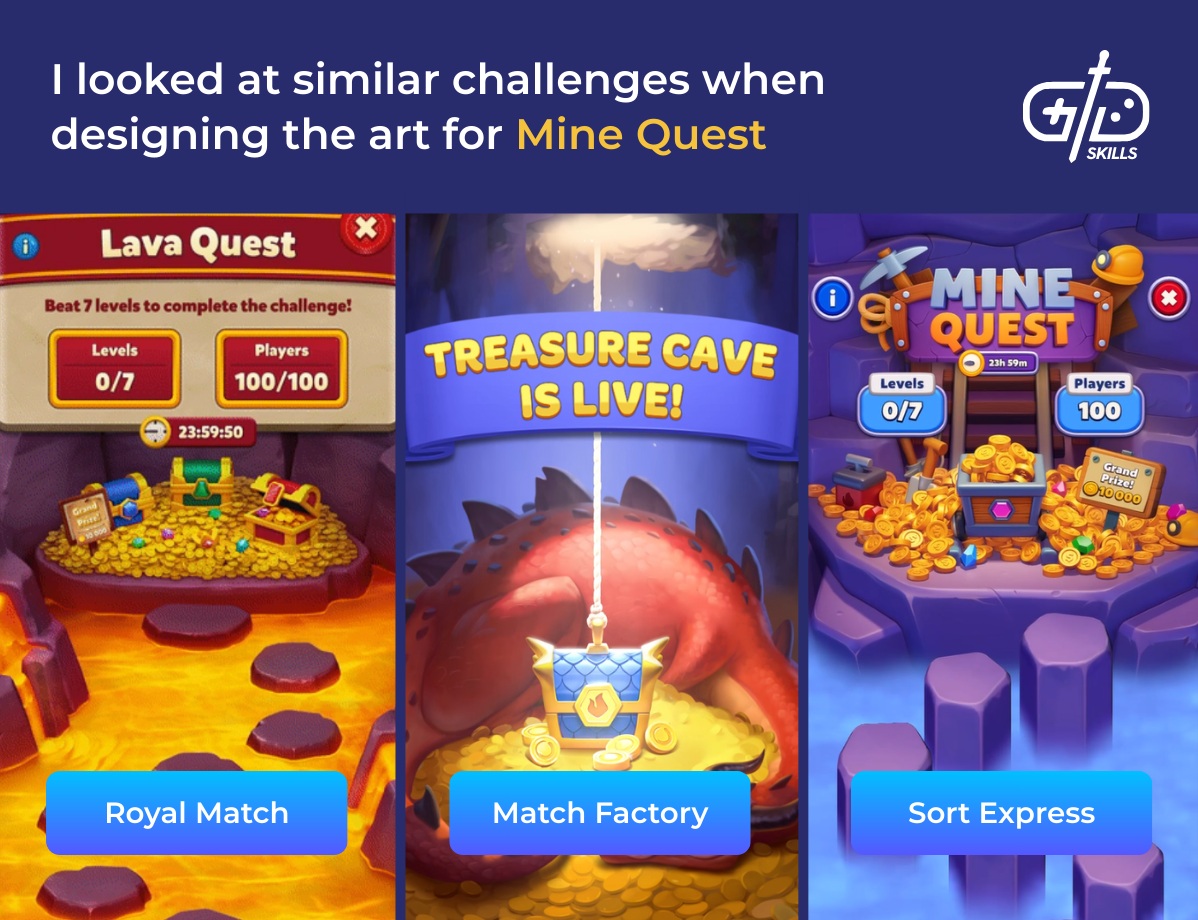

Creating artwork without references is a challenge because game audiences expect genres to look a certain way. Casual puzzle games are a genre where players have deeply ingrained expectations. They often have a reward for getting seven victories in a row, for example. The reward is a large prize pool, and, the more players win the prize, the smaller share each player gets. The event is exciting and tense because there’s an element of luck, but matching that level of excitement and tension with the artwork is a challenge.

I’ve gathered references from other games in similar genres before to make sure the game matches player expectations. I looked at how Royal Match and other similar games handled player failure and how they represented each additional win in the streak. Royal Match calls it Lava Quest, and players step along stones over lava and fall in if they fail. Using this as an inspiration, we decided to use a foggy mine to represent the same event. Players dive deeper and deeper into a mine as they continue, but they fall apart when they fail the quest. This type of quest makes it clear that the event is dangerous, and also that losing means losing all your progress.

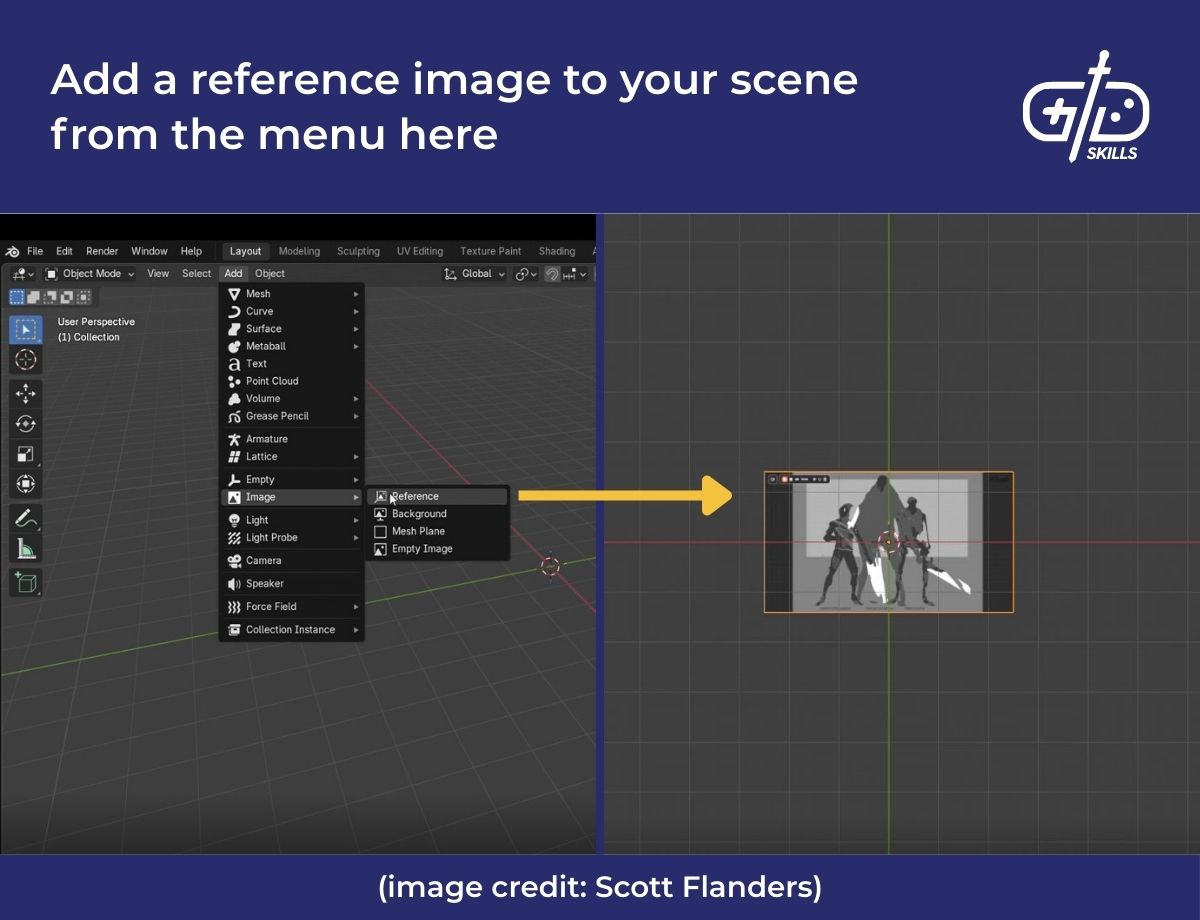

Getting references into blender and annotating them is fairly simple. With a Blender scene open, hit Shift-A to open the mesh menu and then click “Image.” “Add Background” lets you add an image that is only viewable from one angle, while “Add Reference” means it’s viewable from any angle.

The Grease Pencil and Annotators are two other tools for drawing attention to points or sketching in 2D in the scene itself. However, the grease pencil is designed for creating separate, renderable artwork, and members of the community suggest just annotating the image directly before importing it into Blender

2. Determine modeling type

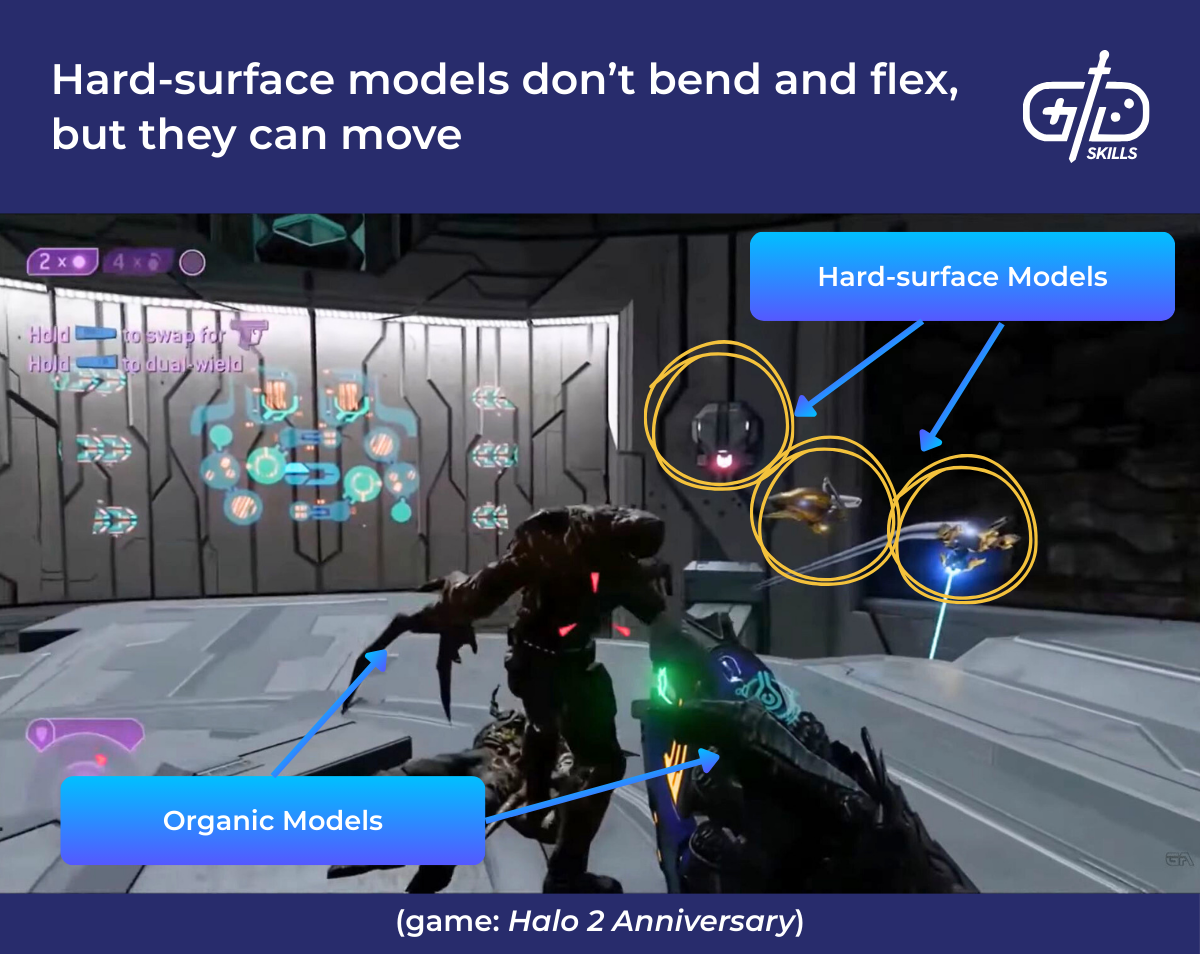

Determine whether the modeling type is hard-surface modeling or organic modeling. Models are hard-surface when they don’t deform. This doesn’t mean that they’re jagged or that they don’t move. A robot, for example, is hard surface: the whole character moves and has curved surfaces, but the surfaces don’t bend, warp, or deform. Organic modeling is the term for creating models that deform like humans, animals, and plants.

Knowing the type is important because it changes the workflow. Artists tend to start either with box modeling for a hard surface model or with sculpting for an organic one. Box modeling means starting with a primitive shape like a cube, sphere, or cylinder and adding, cutting, extruding faces, and combining it with other shapes to create a model. Sculpting is a style that is more intuitive and lets the artist modify the model as if it were clay, which they’re able to do by subdividing the model into millions of vertices.

3. Model the high-poly version

Model the high-poly version using Blender’s box modeling and sculpting workflows. Box modeling for hard-surface models involves some trickery to make the model look smooth and high-res, but Blender has several tools for faking this level of detail. Organic-surface modeling requires advanced sculpting tools, and Blender delivers detailed sculpts through advanced features like dynamic topology and voxel remeshing.

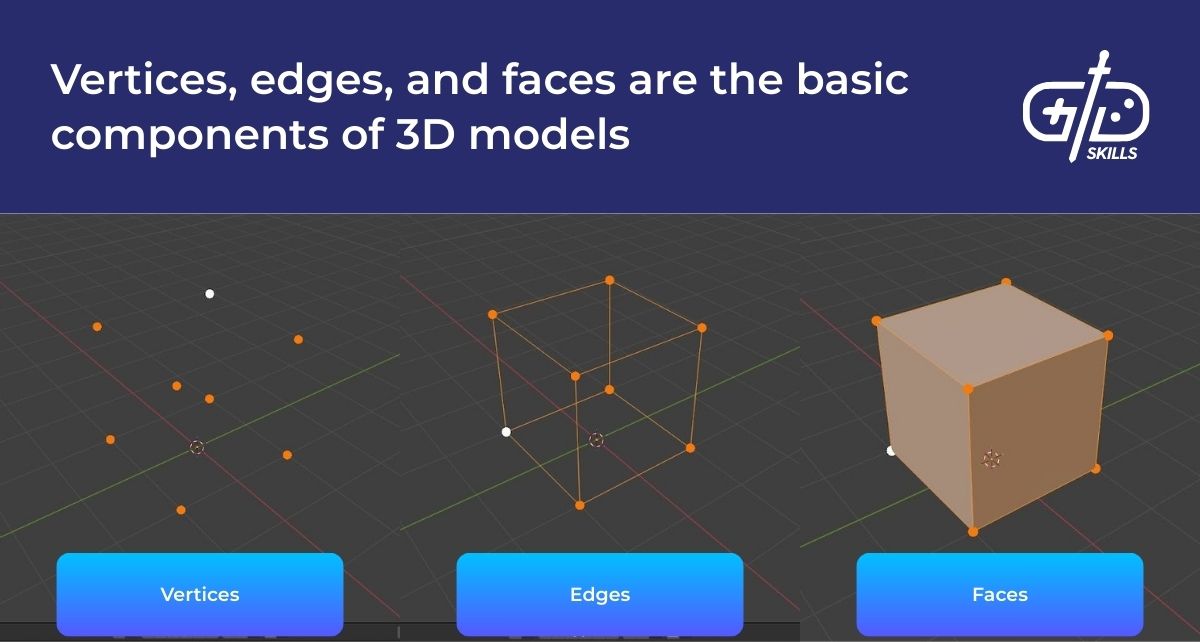

Box modeling is Blender’s oldest and most basic tool. Artists start with a basic shape like a cube and shape it into a more complex model. Understanding this modeling technique first requires knowing how a computer understands 3D models. Each model is made up of vertices (singular vertex), which are a series of points in 3D space. Vertices are only locations, and each model has a series of edges which combine those points into a recognizable shape.

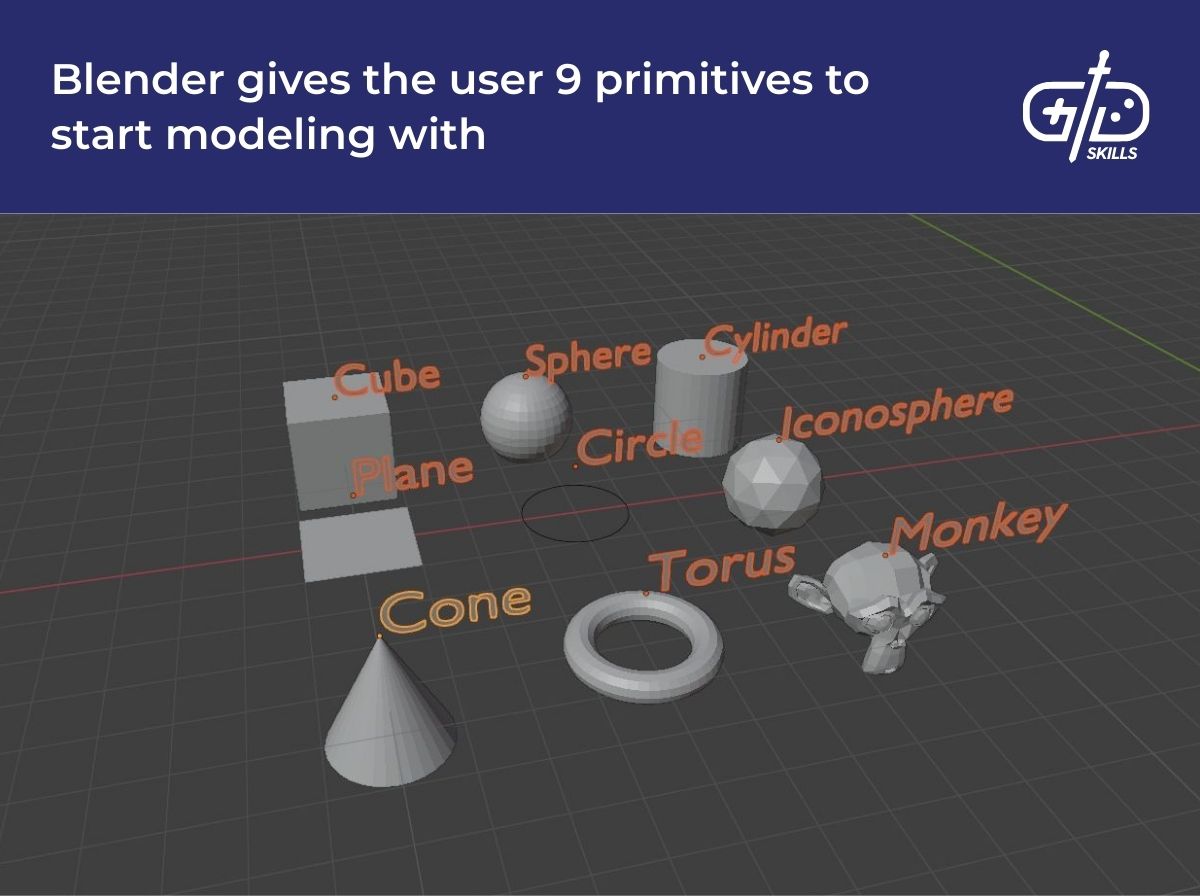

Blender has a box modeling workflow for turning a series of vertices into a model we recognize. Most 3D software already has a few templates of simple shapes called “primitives” made out of vertices and edges. The Blender primitives are accessible through the Shift-A “Add” menu, where users start with flat planes, cubes, spheres, cylinders, cones, and toruses. There’s no room for an in-depth tutorial here, but Blender has shortcuts for many common operations, including adding new vertices, bridging vertices together, adding loops of edges around a model, beveling the edges, and so on.

Blender offers shortcuts to more complex operations in the form of modifiers. Modifiers perform a procedure on the mesh which adds new vertices or changes the shape of the model. The advantage isn’t only that it does a complex task, but that the modifier is removable at any time and instantly reverts to the original model.

Some of the most helpful modifiers at this stage are Mirror and Boolean. Mirror creates a mirror copy of the model in a chosen direction, letting you model only half a symmetrical object and having Blender mirror all changes to the other side. The Boolean modifier lets you create objects by combining them. The power of the tool is that you have the option to combine meshes in different ways. You have the ability to join two objects together into one and build something more complex. You’re also able to subtract from one object by using another. Think of the feature like an old Looney Toons cartoon where Wile E. Coyote smashes through a wall, leaving a coyote-shaped hole. Placing a mesh in another and using the boolean modifier lets you do just that, cutting a hole in a model using another shape.

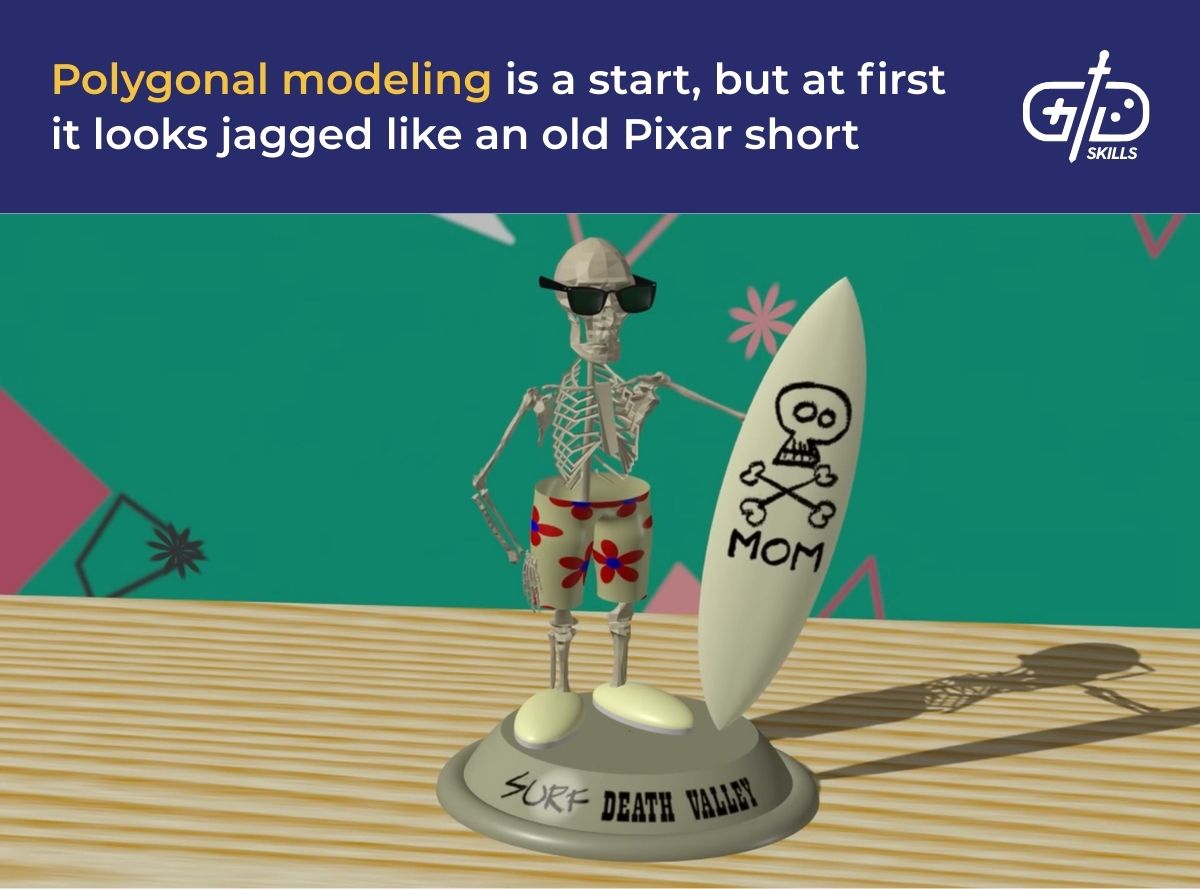

The basic shapes look blocky after box modeling, which is jarring when a hard surface includes curves. Enabling smooth shading on a mesh renders harsh edges as smooth so the final product looks higher quality than it actually is. The model from Pixar’s Knick Knack below shows both styles: the skull isn’t smoothed, but his swim trunks are.

Increasing the number of vertices and faces makes the model look smoother too. Another way to model is to start with box modeling, subdivide the model to double the number of faces, adjust the model, subdivide again, and so on until the final, detailed model is ready. The Subdivision Surface modifier is the tool Blender uses for dividing a model into more faces.

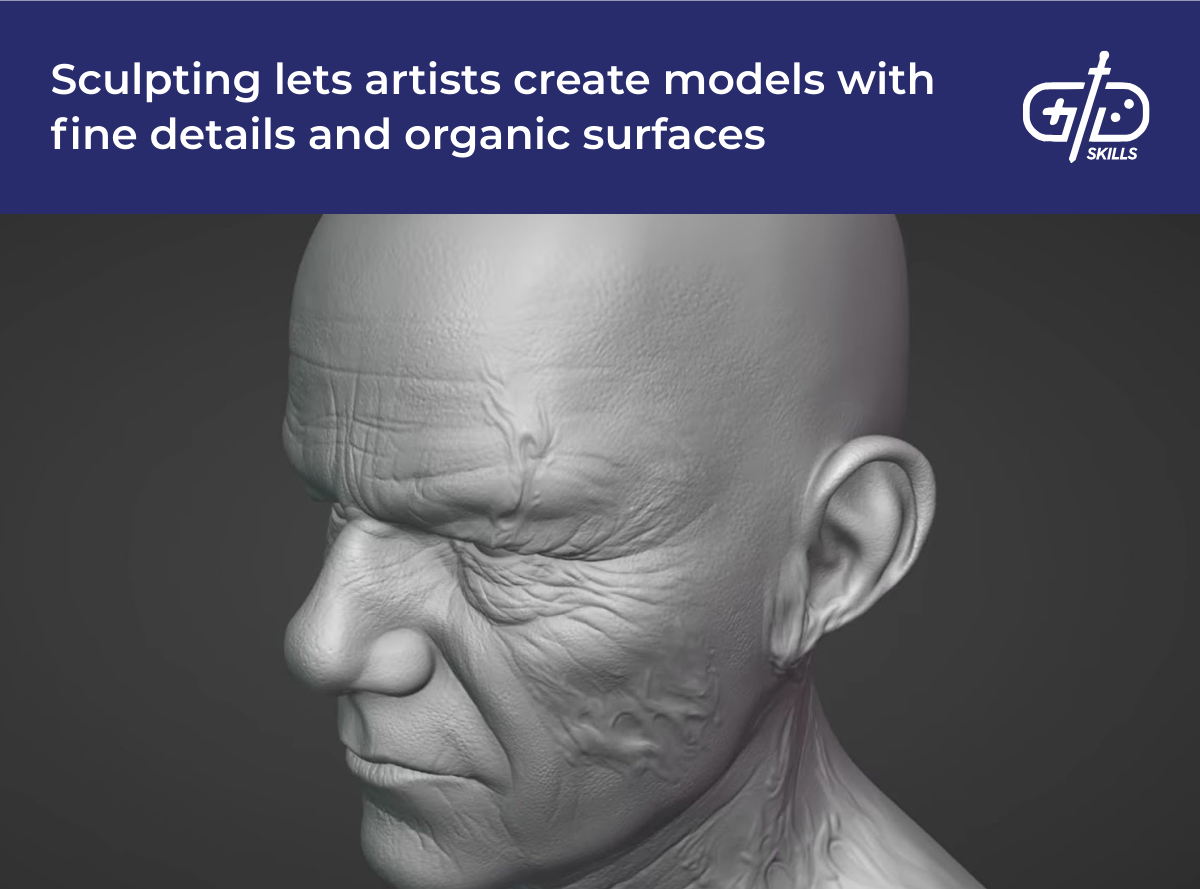

Sculpting is another method for modeling detailed, textured organic shapes like the human up above, since modeling small details like pores one by one isn’t practical. Sculpting lets the artist modify models with brushes. The user drags a mouse (or stylus on a tablet) to edit a model. Brushes crease, flatten, build up, and mold the model like an artist does with clay.

Professionals tend to use other programs like Zbrush for sculpting, but sculpting is possible in Blender too. Blender’s features are just not as detailed as Zbrush. Dynamic topology is a feature of Blender that increases the number of vertices and faces on a mesh, but it only adds detail where you are using the brush. Dynamic topology works well when building up the model with a brush or extruding pieces out since it doesn’t cause stretching. However, Dynamic Topology is a taxing feature, and it also results in a mesh with a chaotic topology. Blender’s Voxel Remesh, done with Ctrl + R in Sculpt mode, lets you retopologize the entire model with evenly sized quads (four-sided faces).

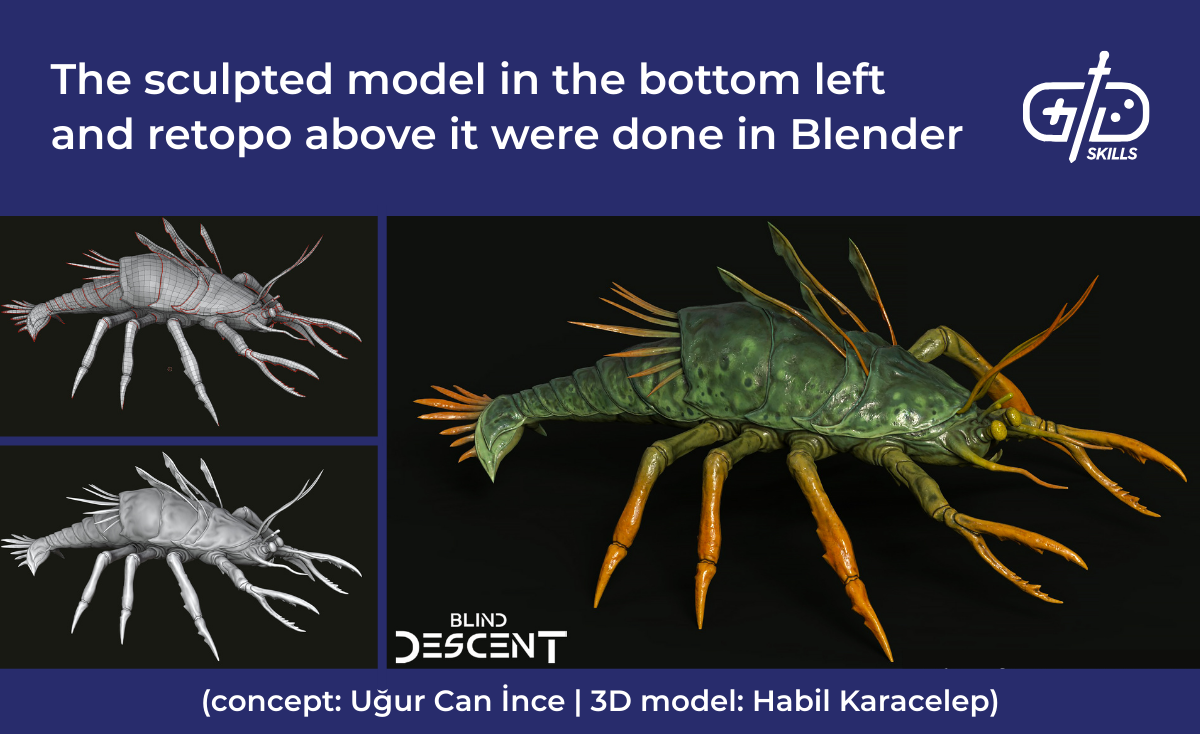

4. Create a low-poly version using retopology

Create a low-poly version using retopology, which means creating a new version of the same mesh with fewer vertices. The low-poly step coming after the high-poly step is a bit unintuitive, but it’s crucial for game development. The high-poly model has up to millions of vertices, which is too many for a game to deal with at 60 FPS. Creating the high-poly model first is both easier because the artist is unrestricted by optimization and lets you save the extra detail to a 2D image later. Blender has three main tools for retopology: remeshing, decimating, and manual retopology with the Shrinkwrap modifier. Before moving on, hold on to the original model, as we want to save the extra detail for the next step.

Remesh and Decimation are both similar tools because they use algorithms to create a lower-poly version of the original. Neither one is effective for models that are going to be animated, since they don’t create extra detail around the parts of the model that deform. Decimate is the simplest modifier, as it only works by collapsing vertices together and then repositioning them as close as possible to the outer boundaries of the mesh. Details that poke out from the surface like ears or noses tend to collapse by this method. Remesh surrounds the object with a series of voxels to generate a new mesh with relatively even topology.

Retopo the hard way with Blender is done with the Shrinkwrap modifier. Retopo this way is a pain (and caused me to start smoking again), but it’s the only way to make a model that is ready for animation. A mesh that isn’t retopologized properly has issues with lighting and deforming convincingly. It’ll look irregular and bumpy like the surface of a crushed car if the topology isn’t solid and simple. Retopology in Blender starts with adding a plane, giving it the Shrinkwrap modifier so it sticks to the surface of the high-poly sculpted mesh, and building on it almost like you are making a cast of the original model.

Add seams around hidden parts of the model as you work on the retopologized version. Seams tell the computer how to unwrap the 3D model and place it flat. This flat projection is called a UV map. The reason for this is that you need to apply a 2D image to a 3D object, which you know is a complex task if you’ve looked at a Mercator projection map and noticed how distorted it becomes toward the poles. A 2D image is going to take an abstract 3D model and make it look like stone, wood, skin, leather, and any other material you have an image for. Artists add seams in hidden areas of the model because, like the poles in a Mercator projection, the most distortion occurs near seams. Hit Ctrl + E to add a seam to the model.

5. Unwrap the low-poly model’s UVs

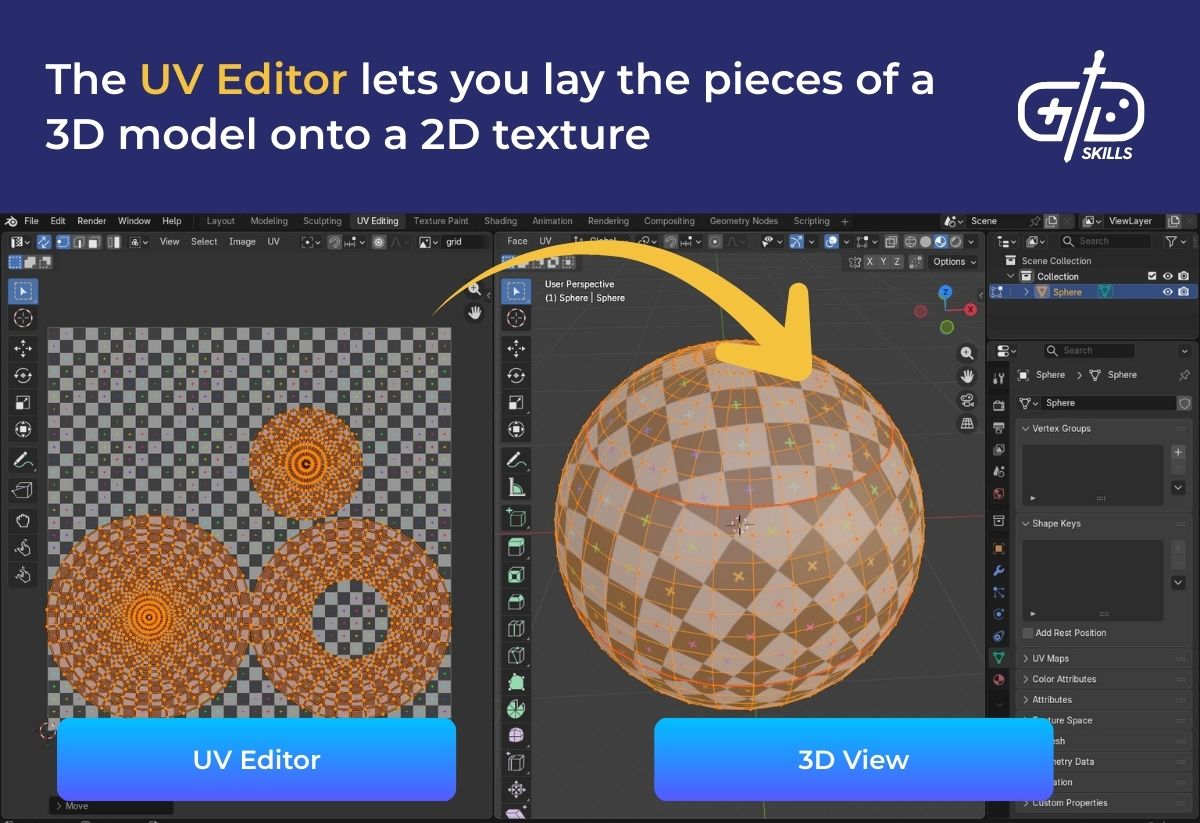

Unwrap the low poly model’s UVs using the seams set in the retopology stage. Recall that UVs are the way a 3D object is mapped to a flat surface. Think of them like stretching and pushing an orange peel to make it lie flat. Blender has a UV Editor for looking at and modifying the unwrapped version of the object. The basic UV editor does miss some of the nicer features in Maya and other professional software, so add-ons like Zen UV help make the process much easier.

Enter the UV editor either by creating a new area and selecting UV Editor from the top left, or hit the “UV Editing” layout at the top. A detailed look at every feature of the UV editor is beyond us here, but the UV editor works similarly to 3D modeling in Blender. You select individual vertices, edges, and faces, pushing them around so they fit on the image texture. Using a default texture like a grid helps you make sure the texture isn’t stretched or doesn’t have visible seams like the one in the image below.

Blender’s built-in UV tools do make getting ideal UVs a challenge. Blender’s automatic unwrapping algorithm struggles with complex and organic shapes, or areas with fine details. The UV editor is also inconsistent when it comes to synced selection, which is when selecting in the UV Editor on the left selects the same part of the object on the right (like in the image above). Not every feature works with synced selection enabled, so it’s a guessing game for the end user whether a feature requires them to turn synced selection off. Other basic workflow tools, like copying UVs between similar objects or changing the order of multiple UVs on export make Blender less efficient than other tools.

Blender is customizable and has several add-ons available for making UV unwrapping easier. A member of the Subnautica 2 team highly recommended Zen UV on Reddit, as he said that the lack of features in the UV Editor was the biggest adjustment new Blender users had to make. UV Packmaster 3 is another tool the community recommends which helps with changing the order of different parts of a model in the UV Editor.

6. Bake texture maps from the high-poly to the low-poly model

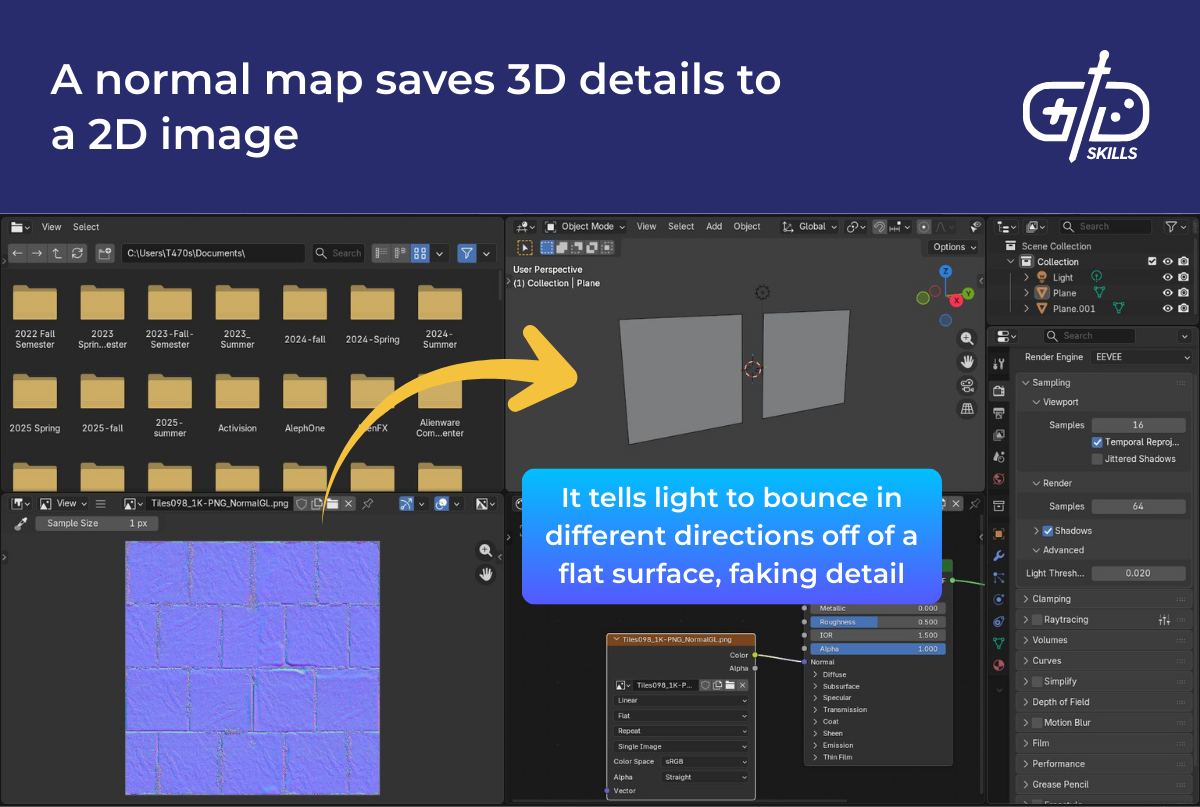

Bake texture maps from the high poly to the low poly model using Blender’s built-in bake feature. Baking is the process of saving the shape details of an object to a 2D image. Saving the detail to an image lets you have the best of both worlds: a well-optimized model with few polygons but many small lighting details.

The step-by-step process for baking from the original sculpt to the final retopologized model is fairly simple.

- On Properties tab to the right, set the Render Engine to Cycles

- In the Material Node Editor for the low-poly object, add an “Image Texture” node, hit “New”, and add an image with a high enough resolution for your project

- Select the high poly model, then Ctrl + click the retopologized model

- Click on Bake in the Properties panel on the Render tab (looks like a Camera)

- Save the image texture with its baked normals

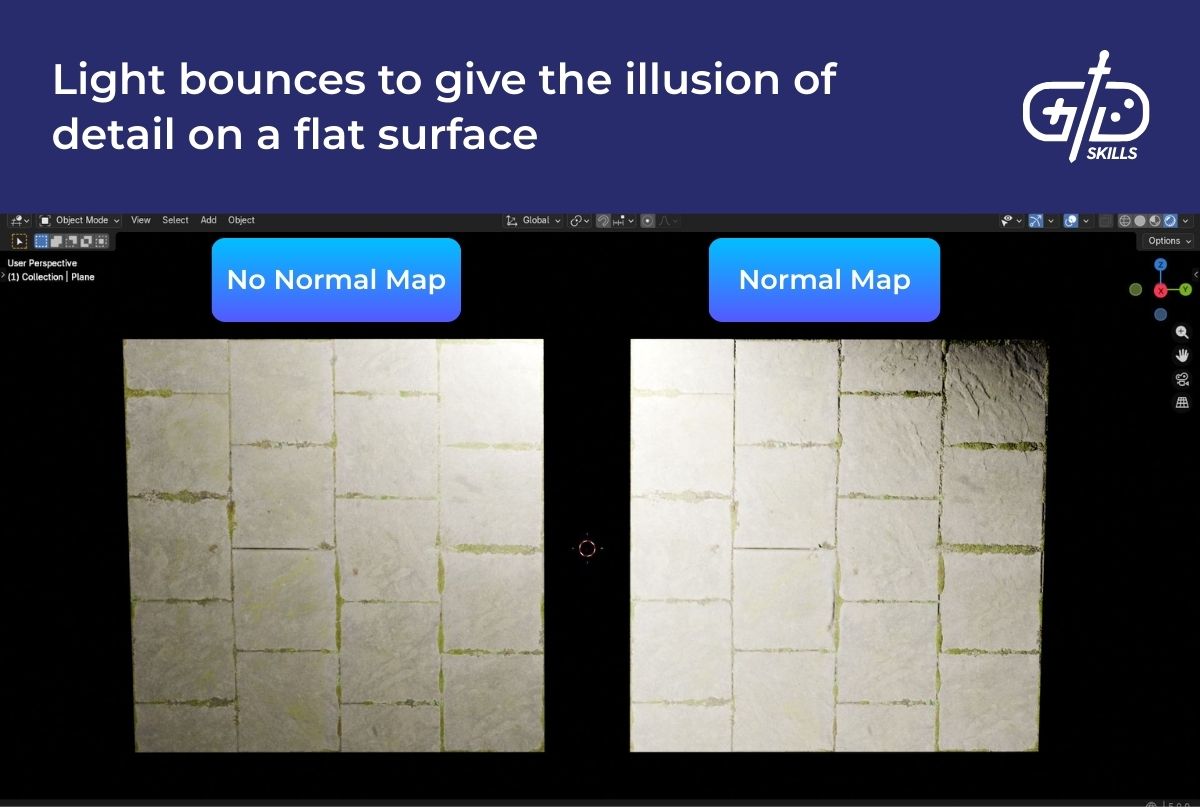

The final image is a normal map. Normal maps make the lighting think there’s extra detail on the model when it’s actually a low-poly version. Each pixel in the image is a 3D X, Y, Z vector that tells light what direction to bounce. The two flat planes in the image below are the exact same as the previous image. All the detail in the version on the right comes from the normal map.

7. Create textures via painting or PBR workflows

Create textures via painting or PBR workflows, which is a separate process from baking maps and means creating the textures that make the model look like a real object. The textures work with the object’s material to make it look realistic. A material says how an object interacts with light, whether it’s shiny or matte, and whether it’s bumpy or flat. Creating these materials and textures within Blender is a challenge, but it’s possible by configuring custom brushes for the texture paint tool.

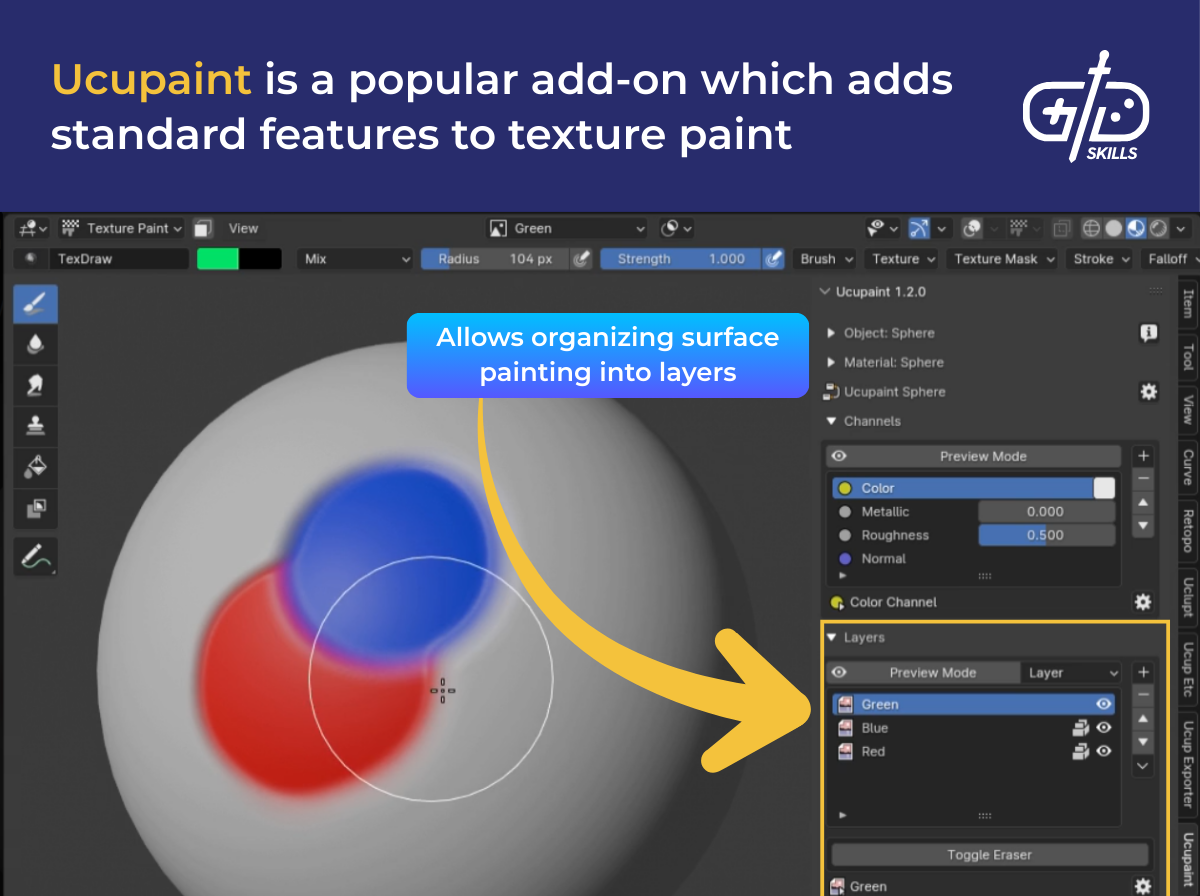

Blender’s texture painting mode is accessed just like Object Mode through the top of the interface. Texture painting lets you paint directly onto the object and have Blender handle matching it up to the UVs. Each brush lets you select a color or texture, and you paint it on with your mouse or stylus. Blender’s texture paint isn’t as advanced as other software like Substance Painter, as it doesn’t support common features like layers by default. Ucupaint is a popular add-on for texture paint that lets you organize textures and shaders into layers if you stay in Blender for the texturing phase.

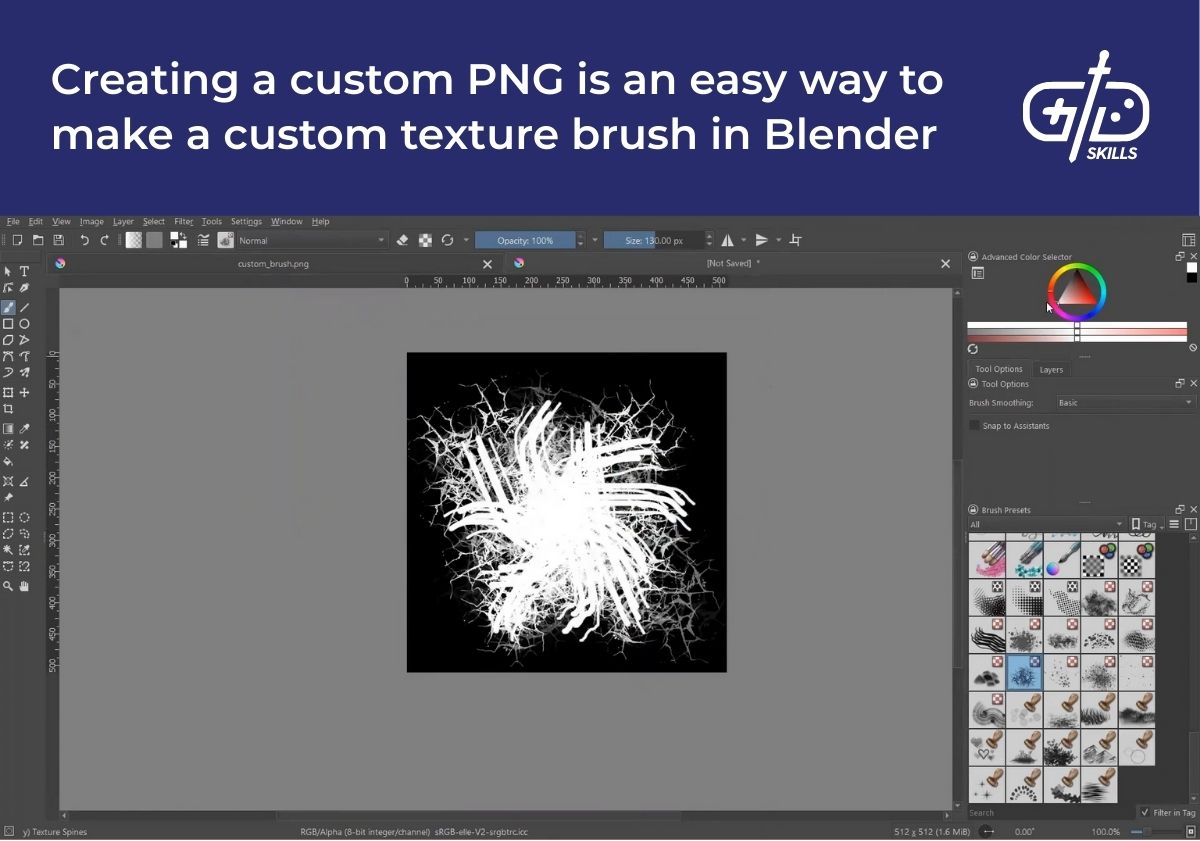

Creating custom brushes for Blender’s texture paint is relatively easy, but you must use third-party software for it. A brush is simply an image where the colored sections are full strength and the transparent sections are minimal strength. Free painting programs like Krita or GIMP let you paint on a transparent surface to create the desired brush from scratch. The format must support transparency, so exporting as a PNG is recommended.

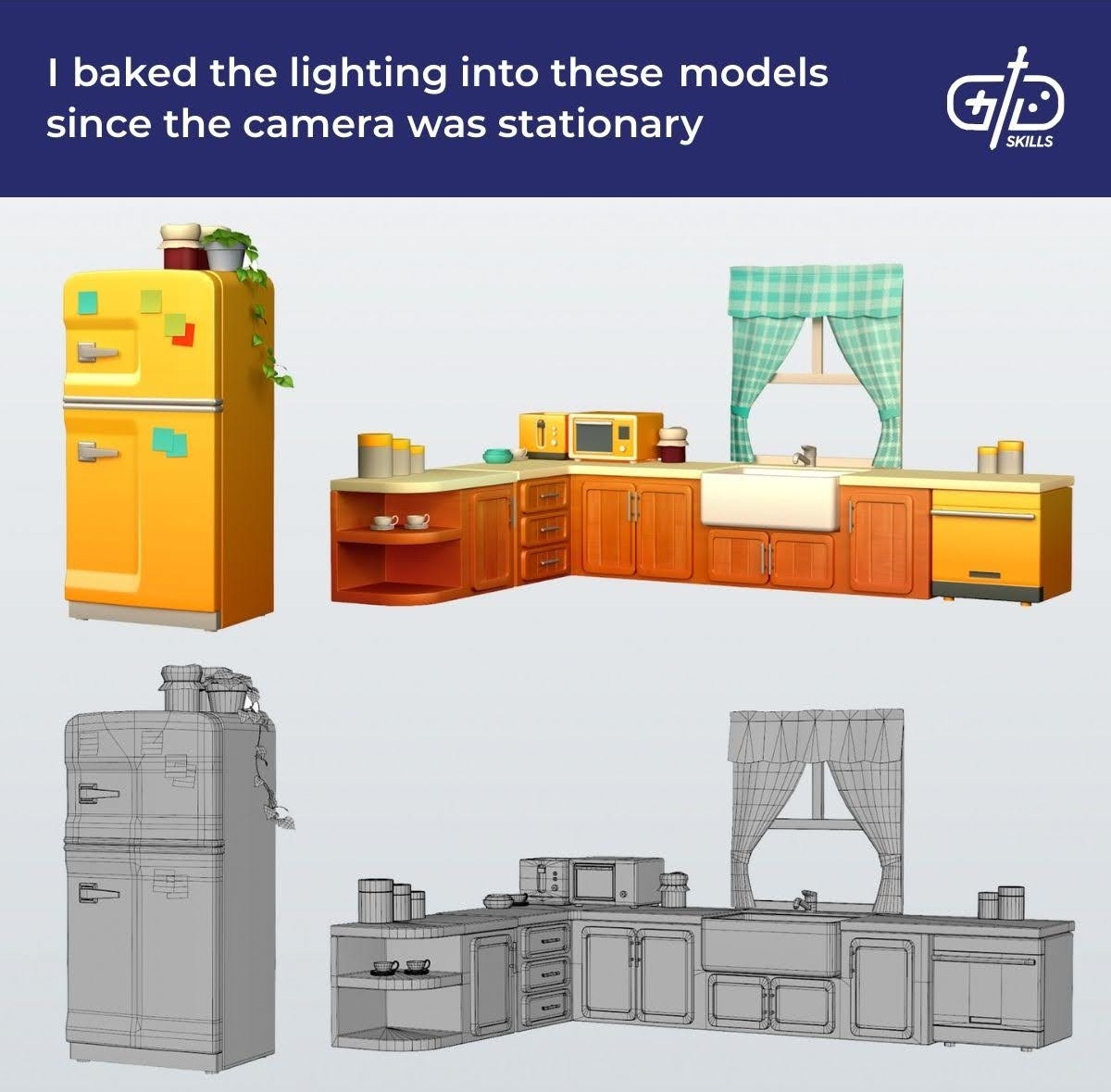

One method I’ve used to create detailed but optimized textures is baking the lighting. The process is similar to baking the normal maps, but instead of just baking the surface details, you bake all the lighting to an image. When I’ve used this technique, I started with no base color textures but just solid colors and normal maps for objects. I created a variety of materials that made each object look like wood, metal, and so on. Once the scene was composed, we baked all the lighting to a texture.The texture stored the color, reflections, and shadows for each object. That way, the game doesn’t need to do any lighting calculations but just loads a texture.

The disadvantage to this approach is that all the lighting effects are saved and will never change. We got away with it here because the scene is viewed from a camera that doesn’t move positions, it only rotates. In that case, there’s no disadvantages to baked lighting. In a game where players are able to close the curtains to block out light or turn on a flashlight, baked lighting alone won’t work because the lighting won’t change.

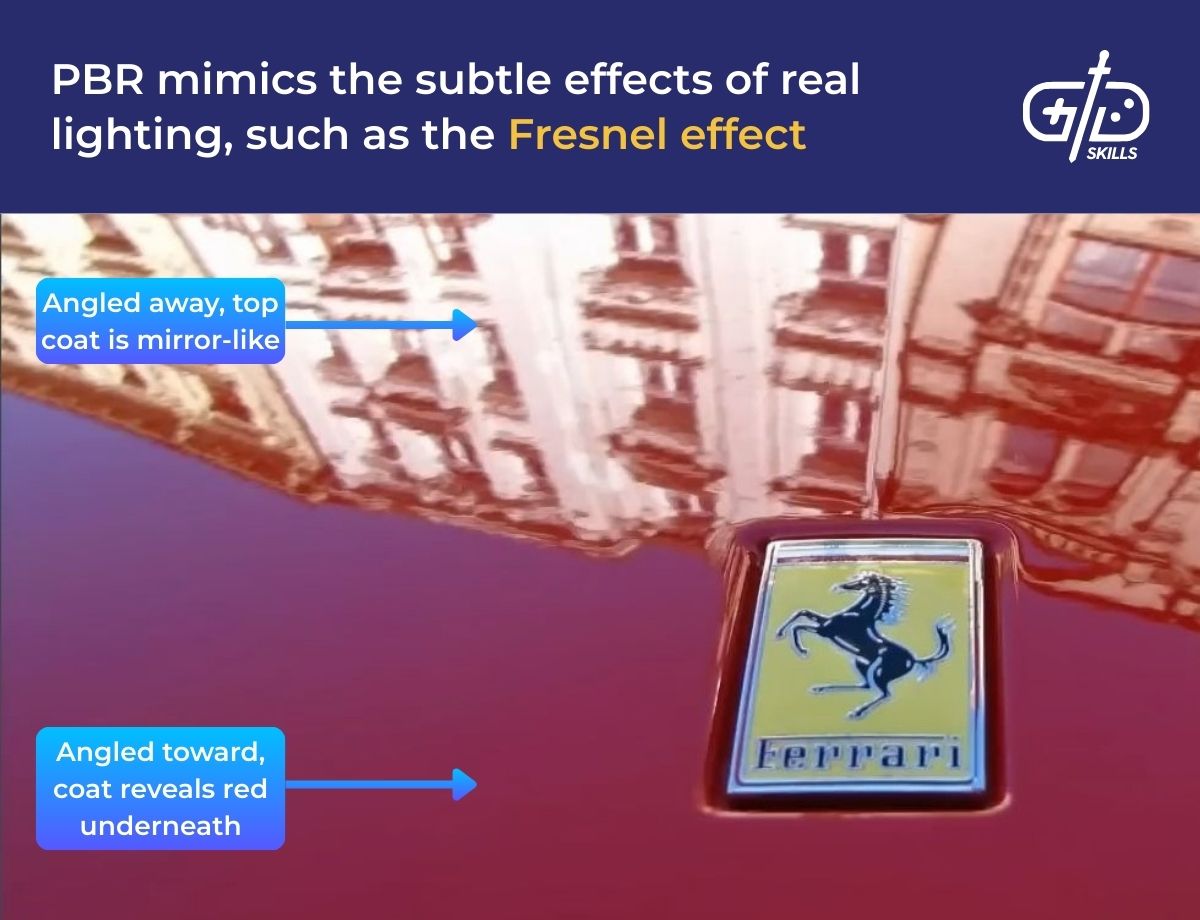

Creating realistic materials and textures takes the increasingly popular PBR (Physically-Based Rendering) approach. PBR is an approach the computer uses to replicate the way lighting works in real-life. Real-time rendering used to use fake reflections with cubemaps or take shortcuts to calculating light. PBR mimics the way light bounces and replicates the subtle realities of lighting. One example is the Fresnel effect, which makes shiny surfaces more reflective when angled away from the viewer.

PBR is possible through Blender’s shaders. The Node Graph lets you change how metallic objects are, how reflective, how rough, and what image textures affect each of these values. Many advanced tutorials are available out there just for shading in Blender, so check out our other GDS articles and resources like Blender Guru and Blender Cookie for information on this specific aspect of the shading process. Using these nodes lets you create the advanced materials I just mentioned and bake the lighting to replicate it in-engine.

8. Export the final asset

Export the final asset using Blender’s extensive export tools to bring it into the game engine or software of your choice. Exporting means dealing with two different file types: the 3D models and the images. Each comes in different formats and will go to the engine separately.

Blender supports exporting 3D models to two common file formats, FBX and OBJ. FBX is the best solution because it stores animation data as well, and it’s the format used by other standard industry software like Maya. Add-ons are available for other formats at Blender’s extensions site online.

The textures used for the assets are a separate file and are exportable from Blender’s image editor. Most game engines support several file formats, so the choice is going to depend on your workflow. JPGs are compressed images and low detail as a result, so they’re not often the best choice. PNG, Targa, and DDS images are all uncompressed and support transparency, meaning they support the highest level of detail. DDS is designed specifically for games and supports mipmaps, which are multiple lower quality versions of the texture. This feature allows the game to switch to lower quality versions when an object is far away, helping the game perform well.

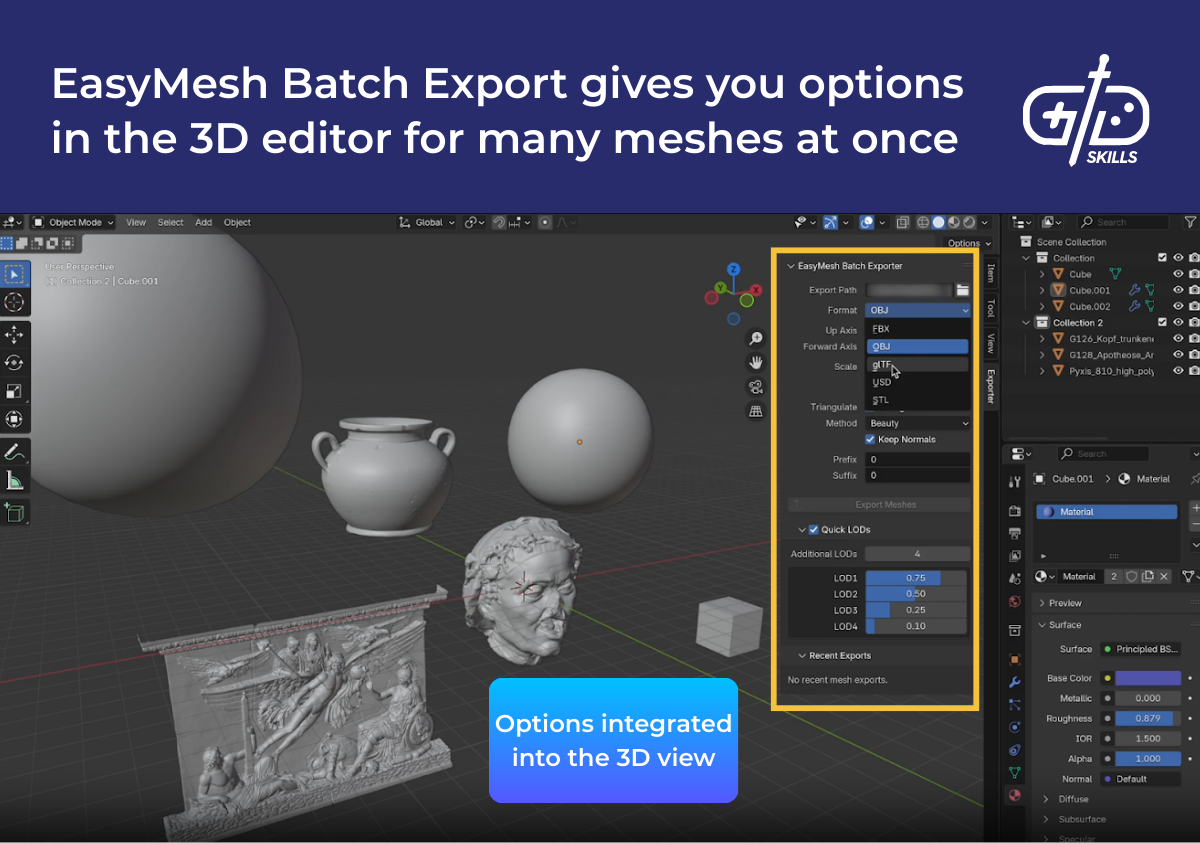

Blender’s library of add-ons helps with exporting these assets to the game engine quickly. Test out several and see which one fits your workflow. Sudip-Soni’s add-on has functions for building LoDs, optimizing meshes, and merging doubled-up vertices. Spec-arte’s EasyMesh Batch Export has pipelines for exporting either to Unreal or Unity.