The Unity game engine is easy to learn, but finding the right learning materials is a challenge for learners when there’s so much content out there. Similarly to beginners learning other big game engines, Unity novices often get stuck in tutorial hell, spending time completing tutorials but never moving on to making finished projects. The projects they do complete using tutorials don’t always combine well with other assets, either, and a complete beginner just ends up frustrated.

Whether Unity is easy to learn is going to depend on the user’s experience. I learned Unity with a computer science background but no experience with game engines, so I have the ability to speak to that perspective. Read on to understand the aspects of Unity that make it accessible and the aspects that make it challenging for beginners.

Is Unity game engine hard to learn?

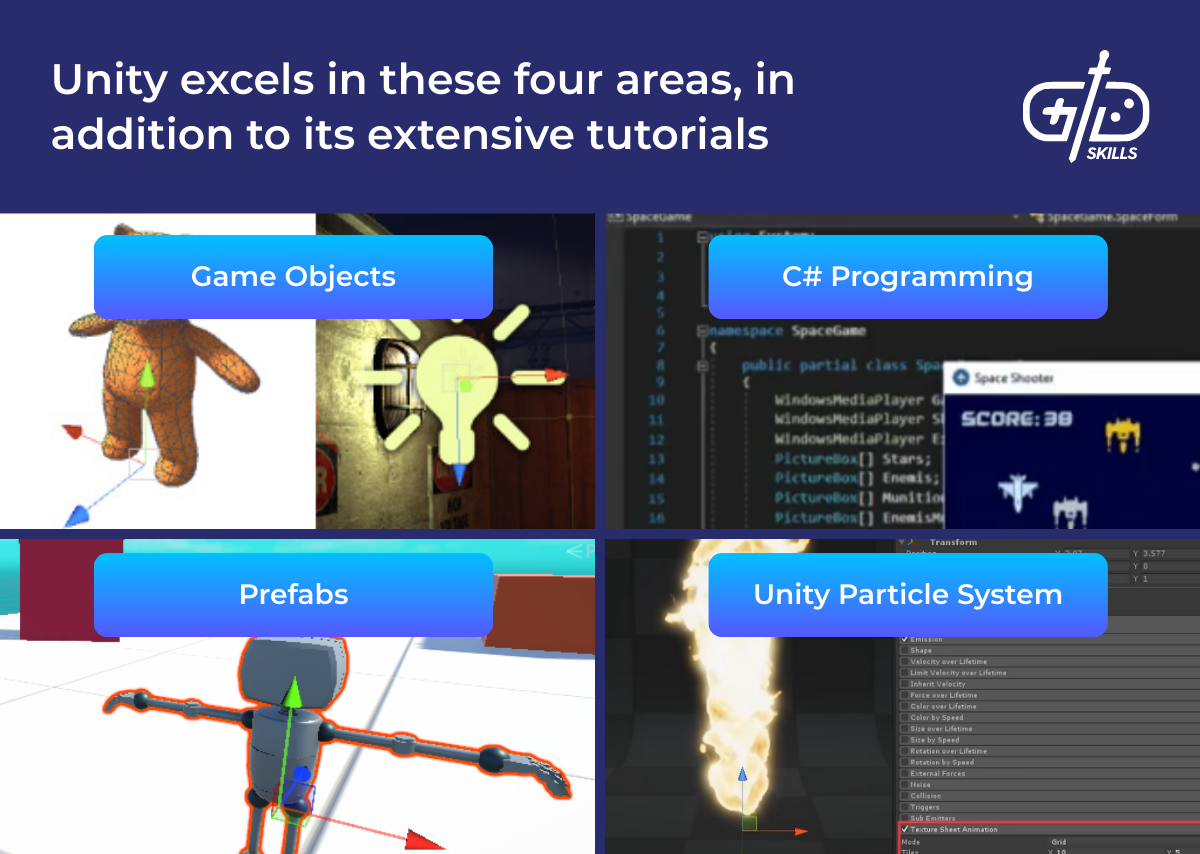

Unity is challenging to learn but more accessible than other game engines with the same capabilities. The advantages of Unity for learning are their industry-standard user interface, GameObjects, prefabs, easy-to-use particle systems, a longer tradition of 2D development than its competitors, coding with the accessible C# language, and the Asset Store full of free and cheap offerings for getting started. Each of these advantages comes with caveats, though. The choice of engine is going to depend on whether the user has experience with code, whether they’ve used other game engines, and how large the scope of their project is.

The interface is challenging for a designer to learn if they haven’t worked with another game engine before. I came to Unity from video editing software, so while I felt confident with coding, I was much less confident with the interface itself. The UI is split into different views, and understanding the purpose each one serves takes some time.

A new user needs to understand the four main views in Unity: the Project panel, the Hierarchy panel, the Inspector, and the Scene View. Each panel works closely with each other. The Project panel is an asset browser for dragging and dropping game objects directly into the scene, whether they’re models, materials, animations, or any other asset. The Scene View is essentially the level, and this panel is where the user views the level’s environment in 2D or 3D space. The Inspector panel lists the properties of the selected Game Object and lets you modify it. The hierarchy panel is for selecting objects, but it has other uses which aren’t as obvious to a new user.

The hierarchy panel lists all the objects in the scene, as not every object is easy to select in Scene View. Some don’t even have a physical body to click on. The hierarchy view comes in handy as a result. Beyond selection, the hierarchy panel allows for creating parent-child relationships between objects. These relationships come quite in handy beyond being a mere organizational tool. A child object stays relative to a parent’s position, rotation and scale. If there’s an object for a character, and a sub-object for their arm, shrinking the character automatically shrinks their arm. Child objects are also useful for visually marking different points of the main object. An example is parenting a child object to a gun’s muzzle, that way there’s a marker to tell bullets where to spawn. All of this sounds pretty useful, now that I’ve said how much utility the parent-child hierarchy has. However, as a beginner, you might still be doing all of this the old fashioned way.

Unity’s interface is also easier to deal with as a new user than its main competitor, Unreal’s. Unreal is the in-house engine built first for Epic Games’ Unreal shooters and then extended over the years as they developed Gears of War and Fortnite. As a result, the engine is more idiosyncratic. Unity has three advantages we’ll discuss here in its interface: the ability to modify the scene during gameplay, more configuration options, and consistent controls across different windows.

Modifying the scene and seeing adjustments real-time in gameplay is a helpful feature for Unity. Iterating on a project and fixing mistakes live makes the learning process a little bit easier. While Unreal does support the ability to modify the scene during gameplay using F8, the changes aren’t saved by default and the user isn’t allowed to open a separate scene window alongside the gameplay.

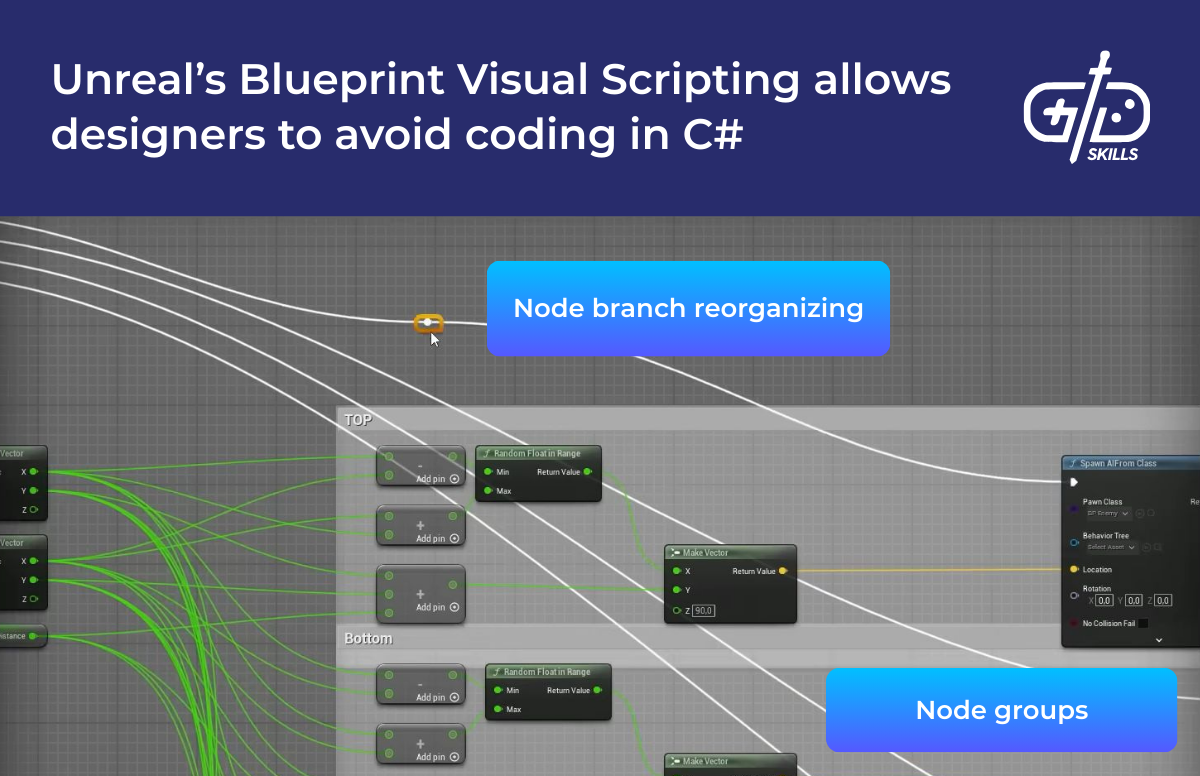

Unity’s user interface is more configurable as well, meaning new users have the option to customize the view to what suits them best. Unity lets users save their project layout when they’re done. Unreal does have the option to save docked windows, but it doesn’t open old layouts by default, nor does it save a layout with multiple windows correctly. The controls between windows in the layout change, too. Shift + Click selects multiple objects in one interface, while Ctrl + Click does in another. The editor for prefabs, which Unity calls Blueprints, doesn’t support box selection like the 3D view, requiring the user to select objects in a scene one-by-one.

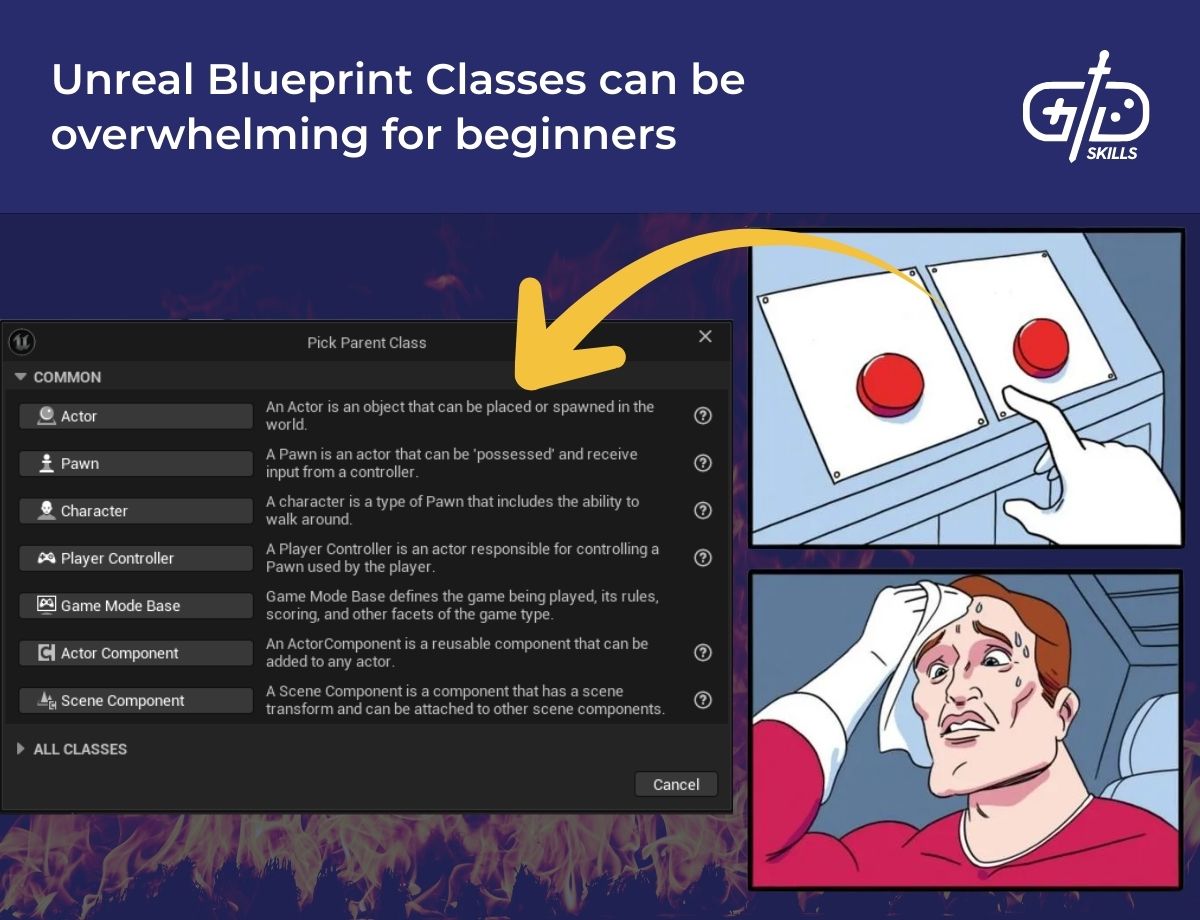

Unity’s Game Objects make it possible to build games in a way that’s more intuitive for beginners. Everything that goes into the scene is a Game Object in Unity and goes into the same hierarchy. Relevant components attach themselves to each game object via the Inspector and are editable from there. Creating and modifying objects is similar for most elements in a game as a result. Unreal, on the other hand, has many different interfaces for different types of assets, which are themselves inconsistently named. Blueprints refer to Blueprint Visual Scripts, prefabs, Blueprint classes, and UI Widget blueprints. The interface for a Blueprint prefab and visual scripts look different from each other, as do other non-Blueprint tools like the particle system. The system is confusing for learners or users coming from a different engine.

Unity’s particle system, 2D development, and UI systems are easier to learn than the alternatives in Unreal. The Shuriken particle system in Unity is integrated directly into the Inspector panel and presents all the options to the user up front. Since Shuriken runs on the CPU, it also interfaces well with other objects in the Unity scene, most notably having the ability to collide with physics objects. Unreal’s Niagara is more powerful given its ability to simulate millions of particles, but using it requires more technical knowledge. Unity’s Particle System gets the job done well enough for a beginner. A Unity dev doesn’t lose anything regardless. The more advanced VFX Graph is available, Unity’s most recent solution for particle systems.

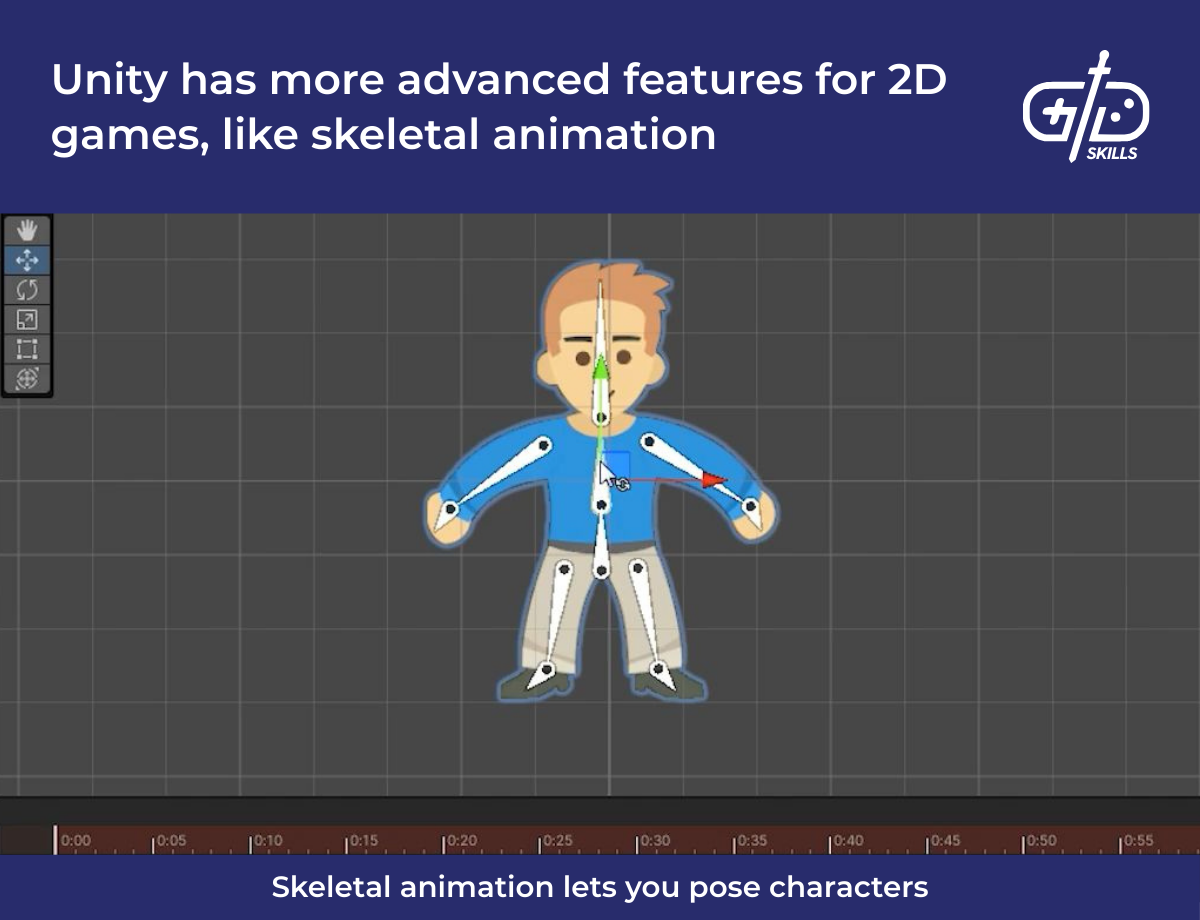

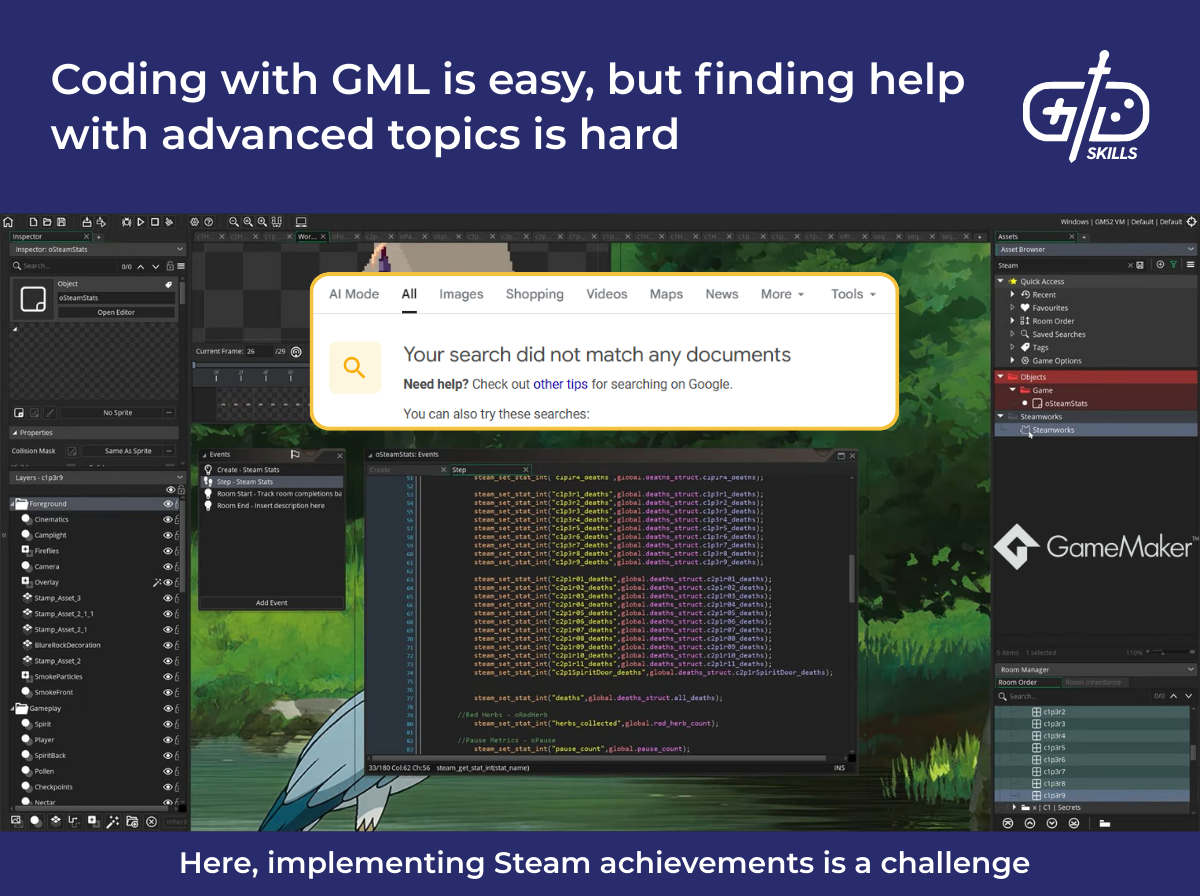

2D development in Unity has such a long history that its tools for sprites, 2D animation, and building 2D scenes are more thoroughly developed than its competitors’. The alternatives are Godot, GameMaker and Unreal. I haven’t personally used Godot, but from the tutorials I’ve seen, it’s a great starter engine! Godot just doesn’t have external tool support like Unity, with ads and user metrics. I’ve tested GameMaker in a game jam setting and found it fun to learn and use, but anything beyond simple concepts gets more challenging to develop. Unreal is difficult to develop with in 2D as it doesn’t support 2D object types, such as sprites, by default. A plugin called Paper2D is required for developing 2D games with Unreal, and the user is locked into this default workflow since there aren’t as many 2D plugins as Unity has for customizing the experience.

Creating UI with Unity’s Canvases (called uGUI by Unity) is simple and easy. Canvases feel rough around the edges at times, but I developed an appreciation for them after I dipped my toes into web-dev to make my own portfolio website. Unity’s system is far more accessible to beginners than Unreal’s. To build UI in Unreal, the user has to follow a specific set of steps to achieve what they want. When changing text, there’s no option to simply modify a component value as with Unity’s C#. The user needs to reference specific names of widgets in code, and some widgets aren’t modifiable. The widget system’s difficulty opens the user up to pitfalls which result in tech debt. Adding a new button instead of creating new instances of the same button, for example, means the designer needs to update each one if they change the style later.

Unity’s Canvases are a system that interfaces well with the rest of Unity. The user adds a button or other UI element into the hierarchy, and the purpose of each element is clear. Since uGUI realizes the UI elements as Game Objects, the user is interacting with and learning the same systems they need to add players and other objects to the scene.

A common source of confusion for beginners is which of Unity’s three UI systems to use. Each system is capable of creating in-game UI, so the choice comes down to personal preference. Canvases are already useful in all situations, so there’s no need to use the others if their workflows don’t sound useful. The other two UI kits are IMGUI and UI Toolkit. Users coming from a web development background are likely to find UI Toolkit easier because it mimics web development, where one file has the UI’s structure, another has the styling information, and another has the code. The asset store has a project called QuizU which demonstrates the system in action for beginners, too. IMGUI requires users to implement UI entirely with code. Being a code-only solution makes it quick for this rough-and-ready UI, especially for debugging purposes, but not for a menu visible in-game.

The user’s background determines whether coding in Unity is easier than Unreal. The downside of Unity is that a beginner needs to learn to code to make a game with it, while the downside of Unreal is that, although coding isn’t required, coding is done in C++. C# in Unity is accessible to coders because of Visual Studio’s IntelliSense, which helps streamline the coding workflow with its suggestions. For non-coders, coding at all is intimidating, so Unreal has the advantage. I haven’t used it personally, but the community considers Unreal’s visual scripting to be more user-friendly. Unity’s visual scripting lacks many features such as the ability to organize connections between nodes or add breakpoints for debugging. The only real downside to Unreal’s Blueprints is that they’re less optimized than code, but this only matters for making large-scale games or optimizing small-scale games for less performant devices.

The Asset Store is a huge advantage for learning Unity because it’s full of freely or cheaply available assets. Unity is a bare bones engine by default, relying on the user to add plugins and extra functionality, but the Asset Store means there’s likely already an extension that helps accomplish your goals. Advanced tools like DOTween make moving objects and animating them ridiculously easy through shortcuts and code.

Implementing assets from the marketplace is quicker and more accessible in Unity than it is in Unreal. My personal experience has been that Asset Store items in Unity are easier to set up. A car controller downloaded from the store isn’t likely to drive how it needs to from the start, but there’s at least a drivable asset available in Scene View. Unreal asset store items tend to require technical knowledge to get working in the scene at all. For example, Unreal’s Combat Fury is a combat asset that implements helpful features like melee combat animations, hit detection, parrying, lock-on, and other features useful for an action game. The asset is pretty similar to the melee assets for Unity, but you only see people using Combat Fury posting killer level stuff they made with it on Twitter.

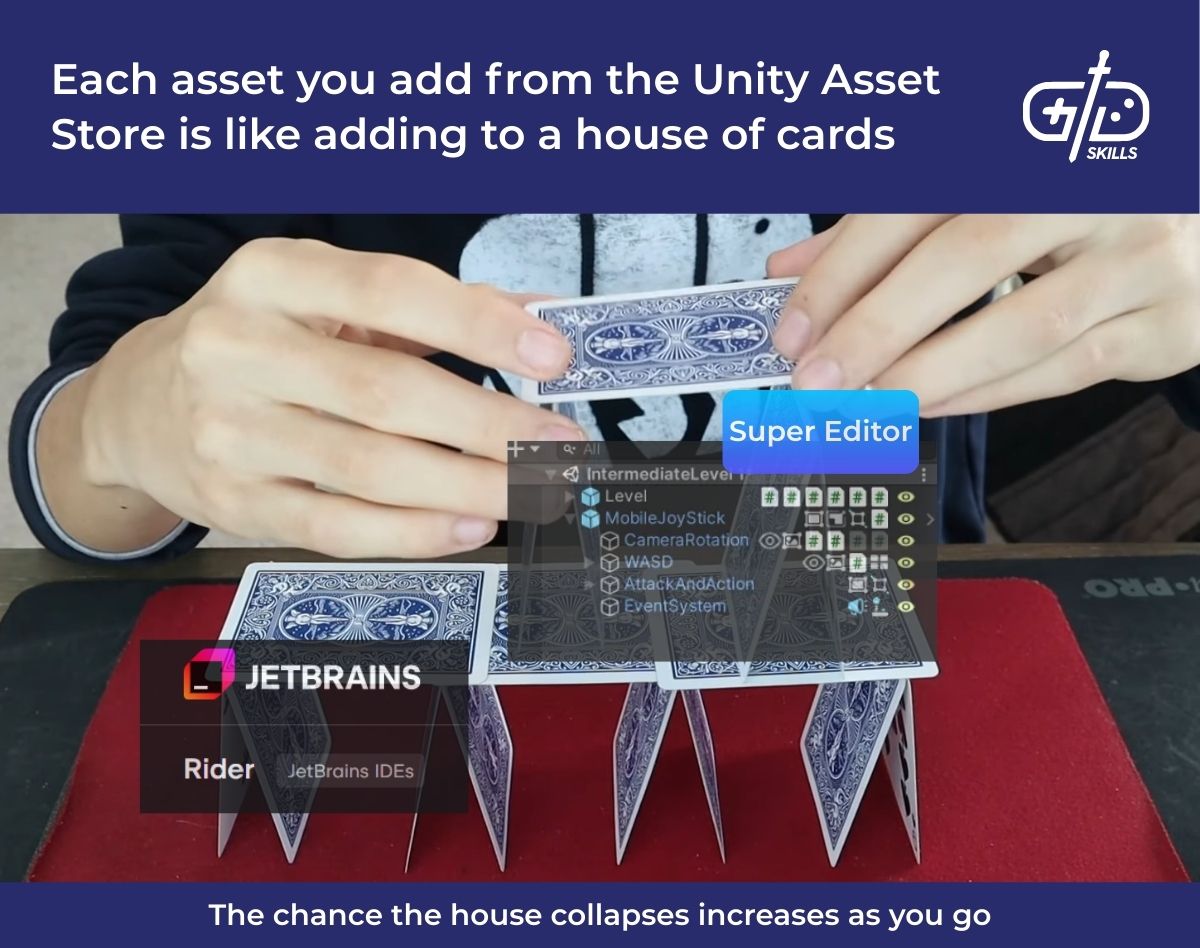

The Asset Store is the perfect segue to Unity’s disadvantages for learners, since it shows how a massive amount of information doesn’t equal accessibility. Unity allows users to take any number of paths to accomplish something, but this means that Asset Store items aren’t extensible or scalable. Adding the system you got from the Asset Store to an existing project is likely to break the whole game and cause plenty of bugs. The lack of scalability is an issue with tutorials as well. Unity has over a decade of extensive tutorials and documentation behind it, but mechanics you build with a tutorial aren’t necessarily going to work in your game as-is. Each new feature and asset has the potential to conflict with old ones and cause failures. This is especially true when new assets have conflicting functions and features, like the Jetbrains Rider and Super Editor IDEs for Unity.

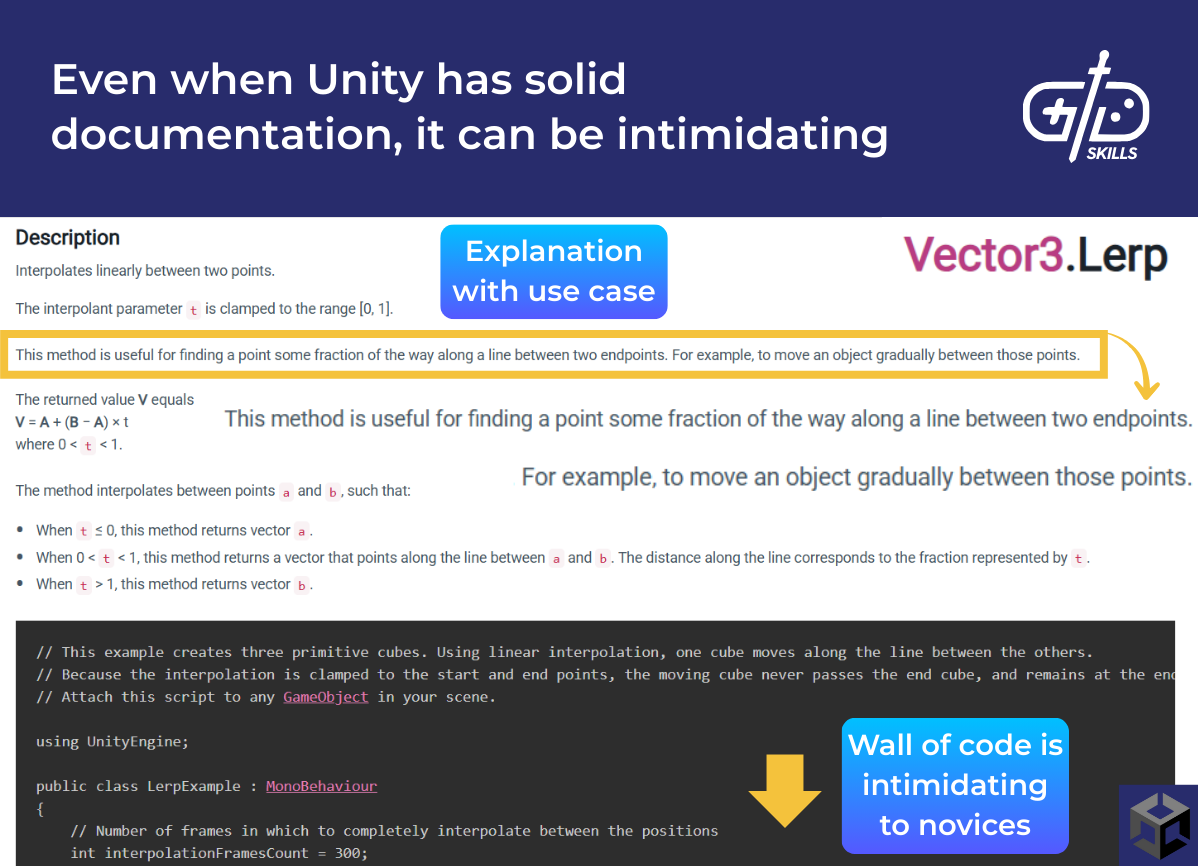

Unity’s documentation is not exactly accessible to a beginner, which means users must go to tutorials or experiment on their own to figure out how to create certain systems and mechanics. To use an example from Unity’s own staff, EditorUtility.CopySerialized() has a one-sentence descriptor in the documentation: “Copy all settings of a Unity Object.” Where it copies the settings, what settings it copies, and what it means for the settings to be serialized all require the user to experiment and figure out. I’ve found Unreal especially unhelpful, with even the best part of the documentation giving only abstract information and no examples of what the feature is good for and how to use it.

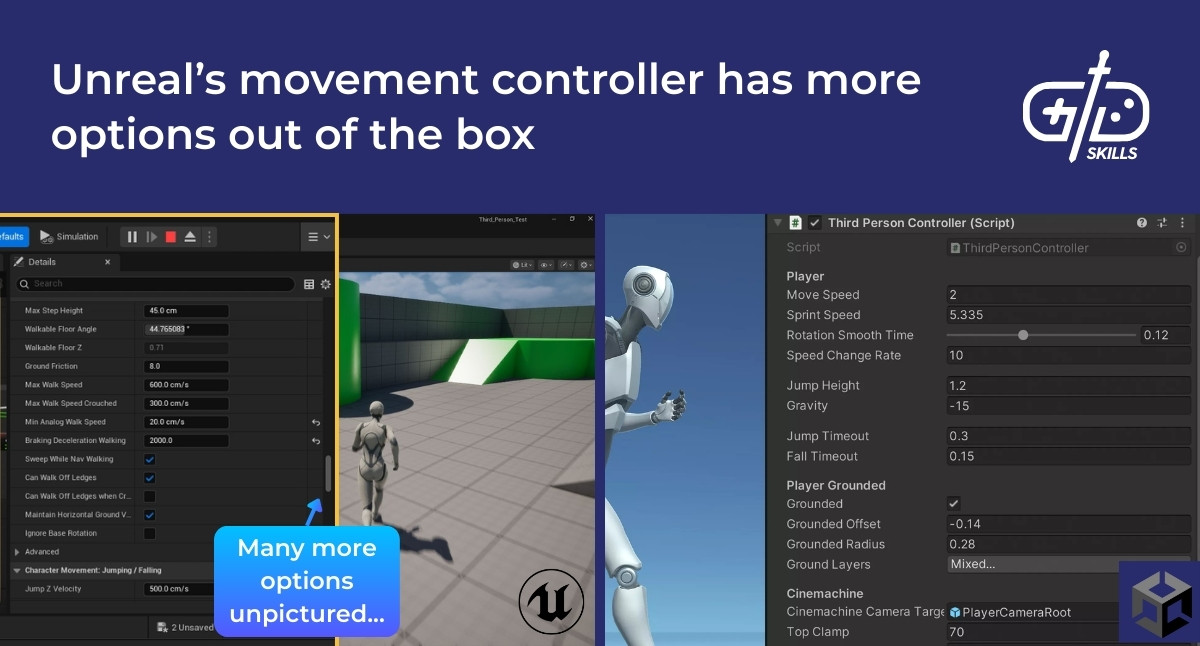

Creating in Unity requires building or installing many custom packages to create all the features a game needs. The advantage to Unity’s approach is that it doesn’t overwhelm beginners with its options like Unreal does. The disadvantage is that getting started with simple features like movement controllers, vehicles, or inventory systems requires finding solutions in the asset store or building from scratch. Unity asset store items aren’t always the most compatible, performant, or useful for a particular project, so the most advanced functionality is challenging with Unity. Getting a movement controller working in Unreal, for example, is dead easy in comparison to Unity once the user’s learned the engine. Unreal comes with first and third person controllers built-in with settings for step height, drag, protection from walking off ledges, and so on.

Unity is enough of a barebones template that a purpose-built engine is better in some cases. I found Game Maker very easy to learn for the game jam I worked on. Game Maker is designed for 2D games, so it’s streamlined to make the process of creating in 2D as easy as possible. The engine has its own scripting language called GML which is forgiving for beginners. The visual scripting is even easier, and converting it into GML code makes it easy to get familiar with the code part.

RPG Maker is a simple solution that pares features down to only those relevant for top-down, 2D RPGs, making it a quicker solution than Unity in that case. The engine is designed for ease of use much like GameMaker. Virtually all modifications are done through an interface rather than code, whether creating new abilities, enemies, or level layouts. The toolset is limiting, as it locks you into certain features like grid-based movement, but this makes it a better tool for those who have the money for the one-time fee required to install.

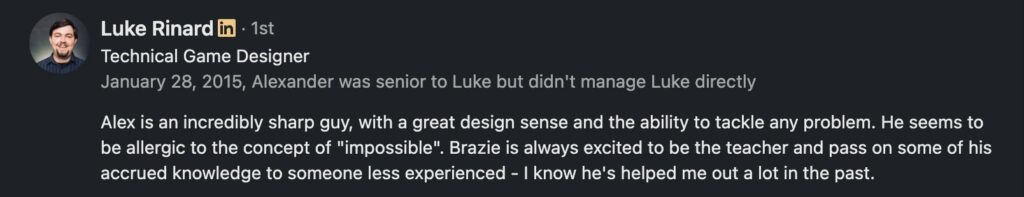

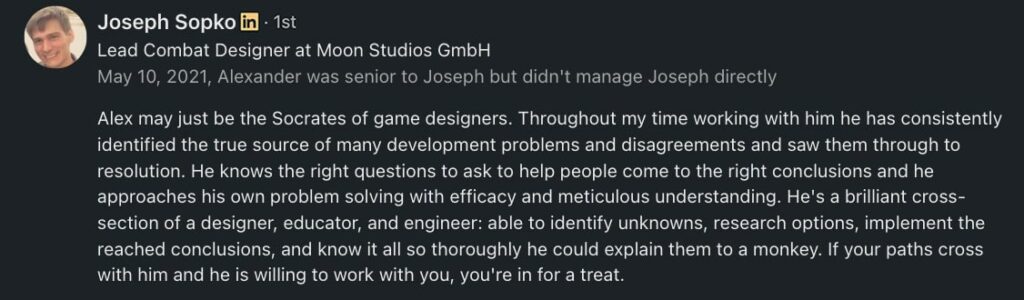

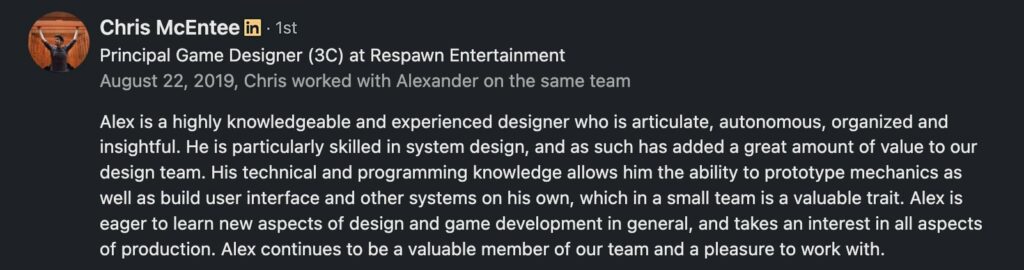

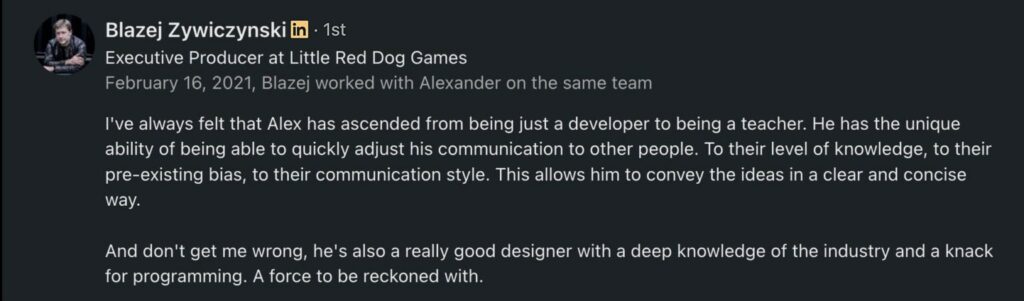

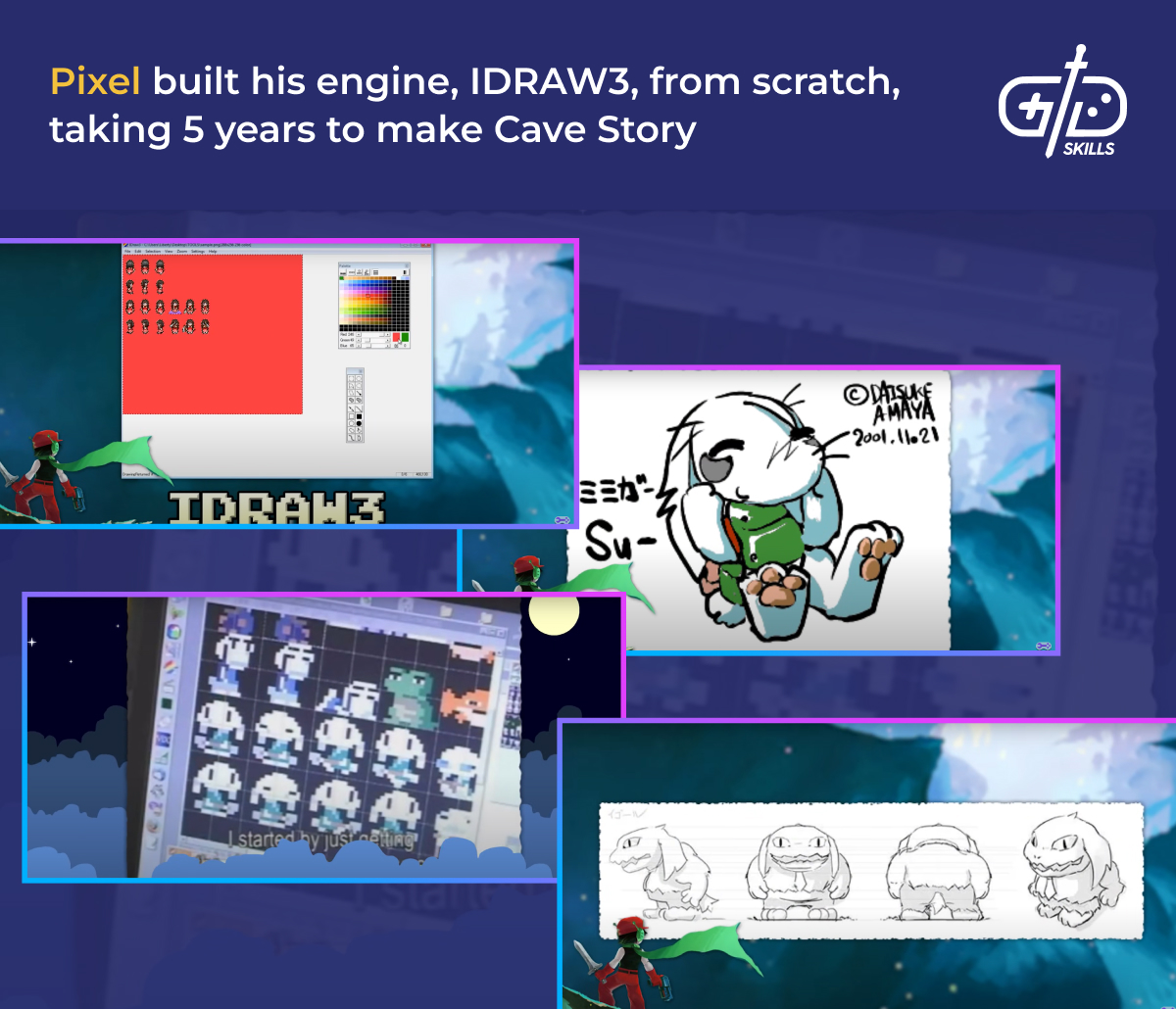

Unity was my first engine, so I’ve tagged in Alex Brazie to give his own two cents here as a designer who moved from other engines to Unity for Ori and No Rest for the Wicked. As he says, Unity is easier for the most basic 80% of functions. The advantage is that it’s prebuilt. Building an engine from scratch requires building systems for rendering, input management, and editing functions. The majority of developers have no reason to go through this time investment when tools like Unity are available. A hobbyist like Pixel, who spent 5 years making Cave Story, has time to start from nothing, but most game developers don’t have the resources to devote to making custom tools.

The fact Unity is prebuilt locks learners into an inefficient workflow, though, which causes problems when high performance is required. Unity’s entities are based on MonoBehaviors, which handle updates such as when an entity appears, when a button is pressed, when a new frame begins, and so on. A new Unity designer handling events through MonoBehaviors is going to put a burden on performance. Capable programmers with source code access have the ability to disable the worst of Unity’s events – OnUpdate(), OnFixedUpdate(), OnEvent(), among others – and create a custom event registration system, like Alex’s team did on Ori and No Rest for the Wicked. Most designers don’t have to worry about these issues, but a complex or large project is going to need custom solutions for Unity.

Is Unity engine good for beginners?

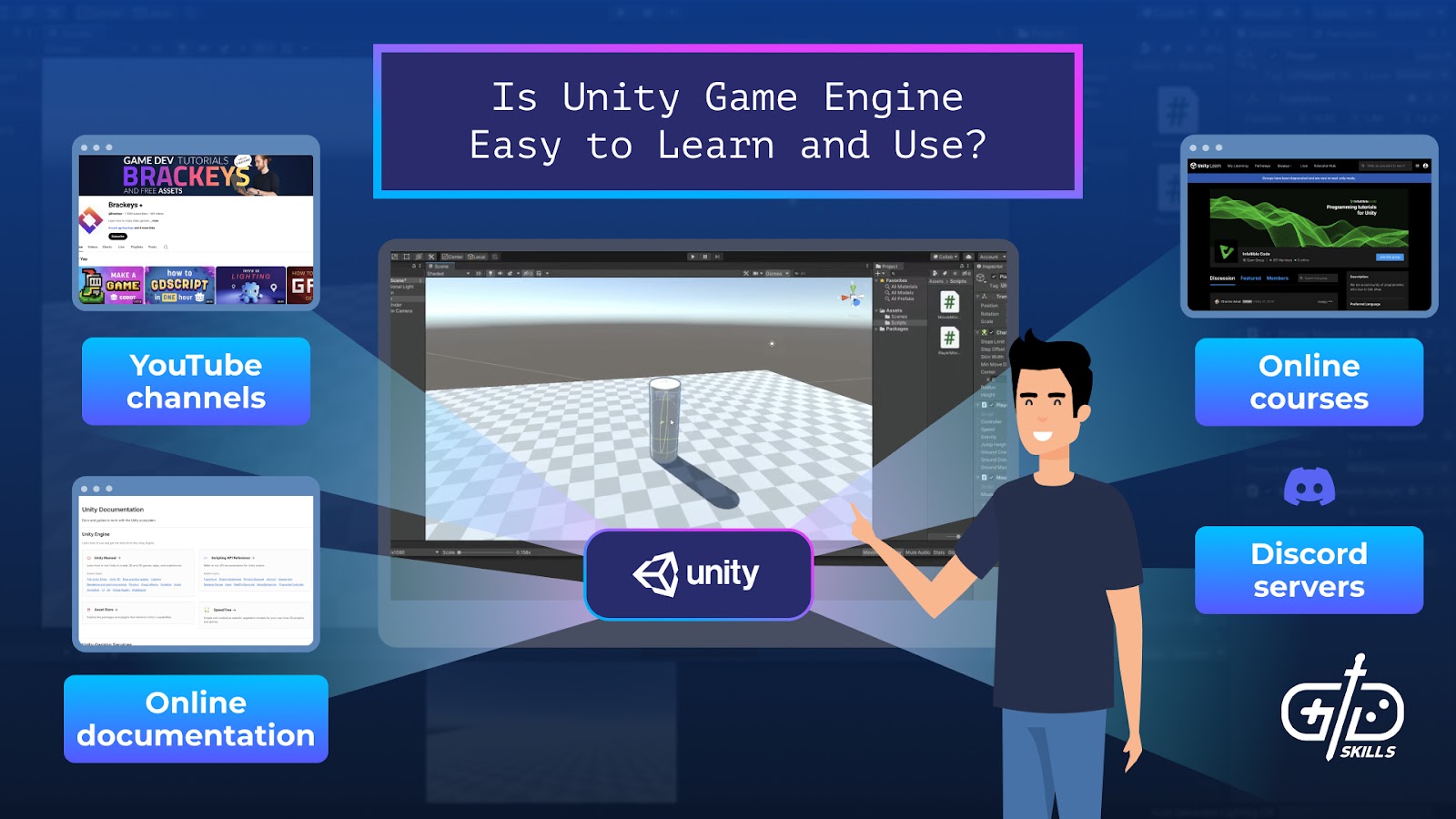

Unity is challenging to learn but a powerful tool for beginners because the resources for learning are so extensive. Discord servers, YouTube channels, and courses have been growing and improving for nearly 20 years now. Beginners have thousands of tutorials to learn from, but the mass of content makes finding the right material daunting. A beginner has no way of knowing which tutorial caters to their learning style, as many tutorials cover irrelevant information, use too much jargon, and assume knowledge the viewer doesn’t have. Every experience is different, but I found a selection of Unity’s official learning resources to be the best for a designer learning Unity as their first engine.

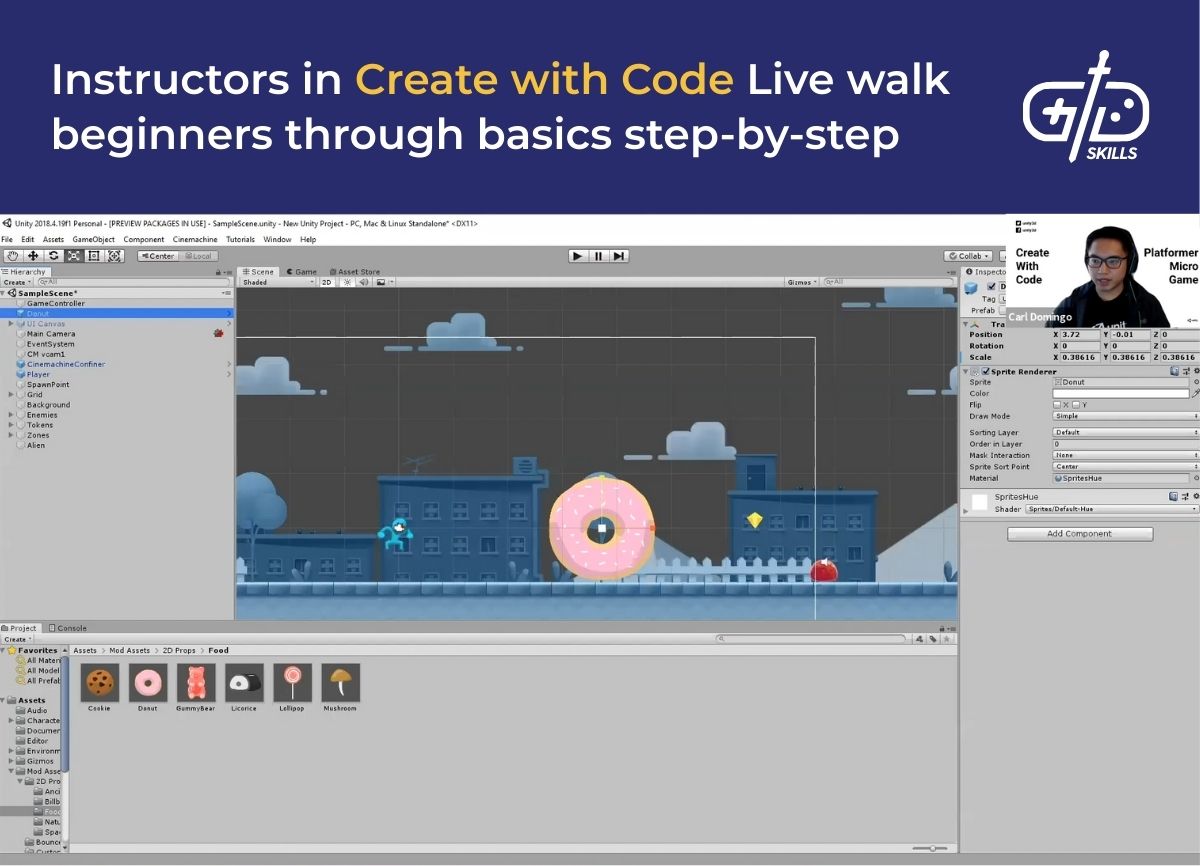

I felt I was able to actually create something with Unity once I took the Create with Code Live course. Some other official Unity courses were descriptive in ways that did not show me the ropes and had a presentation style that was hard to follow along, but Create with Code Live was one of Unity’s best courses. The course guides users through the main features of Unity and builds in room to explore the tools as well. It’s composed of a series of livestreams and homework assignments intended to be completed over seven weeks. Unity hasn’t taught the course since 2021, but all the old versions are available for free online. I attended the one in 2020 and highly recommend it.

YouTube is a deep resource for tutorials but a large amount of the content doesn’t teach practices that are applicable to many projects, and, when you’re just starting out, it struggles to break concepts down to a beginner level. Even popular channels like Brackeys seem too fast paced for a beginner. As a more experienced developer, the content doesn’t always apply to your project either, since it’s built in a very simple and non-scalable fashion.

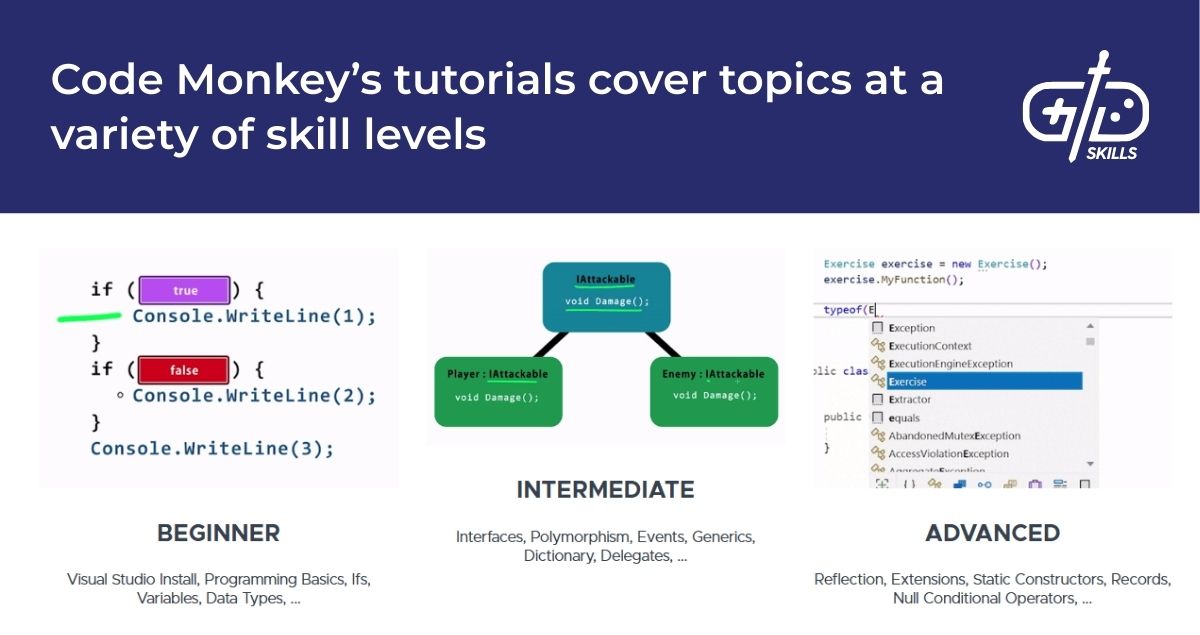

InfallibleCode and Code Monkey are two of the most helpful YouTube channels for breaking concepts down in a practical way. Infallible Code’s tutorials focus on more than just building example projects. He discusses and explains best practices for implementing a feature. Most Unity tutorials show a method for building a game but don’t do so in a way that is the most efficient or likely to work well in a larger project. Infallible Code discusses writing clean code, using paradigms in Unity like Entity-Component Systems, or just breaks down programming concepts in short, to-the-point tutorials.

Code Monkey is still active, unlike InfallibleCode, and has beginner-friendly resources on his website for learning to write C# in Unity. The course on his website is paid, but all the videos in the course are accessible for free through his YouTube channel. The course adds an interactive Unity project with exercises and access to Hugo Cardoso, the channel’s creator, for help, but they aren’t required to start learning.

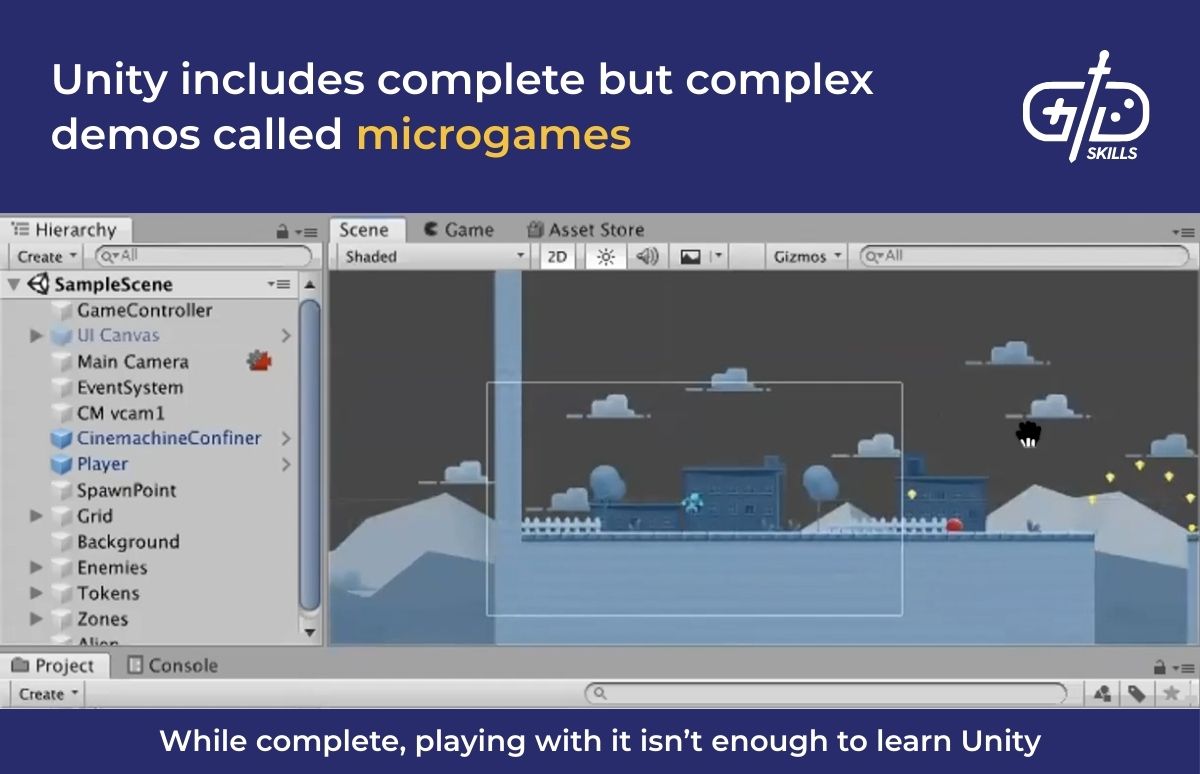

Unity includes micro-projects which are small, complete experiences that are meant to teach Unity but are too basic to teach anything useful while too complex to be easily broken down from their code. Exploring the project is valuable since it lets you see how a full game is put together, but the code is impenetrable even looking back on it now. Instead I recommend following along a course to build a specific project, then making changes to it after you’re done to make your first game. That’s what laid the foundation for my first commercial game Hunting Spree.

The Unite Conference is another learning resource available for users. The annual conference holds talks, courses, and gives attendees an opportunity to network with other Unity devs. The ticket price changes from year to year, but it’s often above $500. Most who go to the conference do so with funding from their employer. If there’s the opportunity to go, the advantage isn’t seeing the talks as much as it is getting to talk directly with the people who work on the engine.