MOBA (multiplayer online battle arena) games are strategic, highly competitive PvP experiences that popularized a niche game mode from the RTS genre. The MOBA design industry is a challenging arena to enter, as new developers walk in the footsteps of industry titans. Riot Games has become a multi-billion dollar business through League of Legends’ mainstream popularity. Blizzard entered the genre with Heroes of the Storm, but they’ve since stopped supporting new content for the game, showing that even AAA studios struggle to maintain service for these experiences in the long term.

The popularity of MOBAs means there’s always room to find a niche, though. Hi-Rez’s Smite 2 beta pulls in thousands of players each day with its roster of mythological figures and limited third person perspective, even if it’s not a League of Legends killer. However, knowing where to begin making a MOBA is a challenge. Read on for a deep dive into the mechanics, character design, and balancing process that make a MOBA a MOBA, broken down by a former Riot Games designer, and come away with templates for getting started.

What are the fundamentals of MOBA game design?

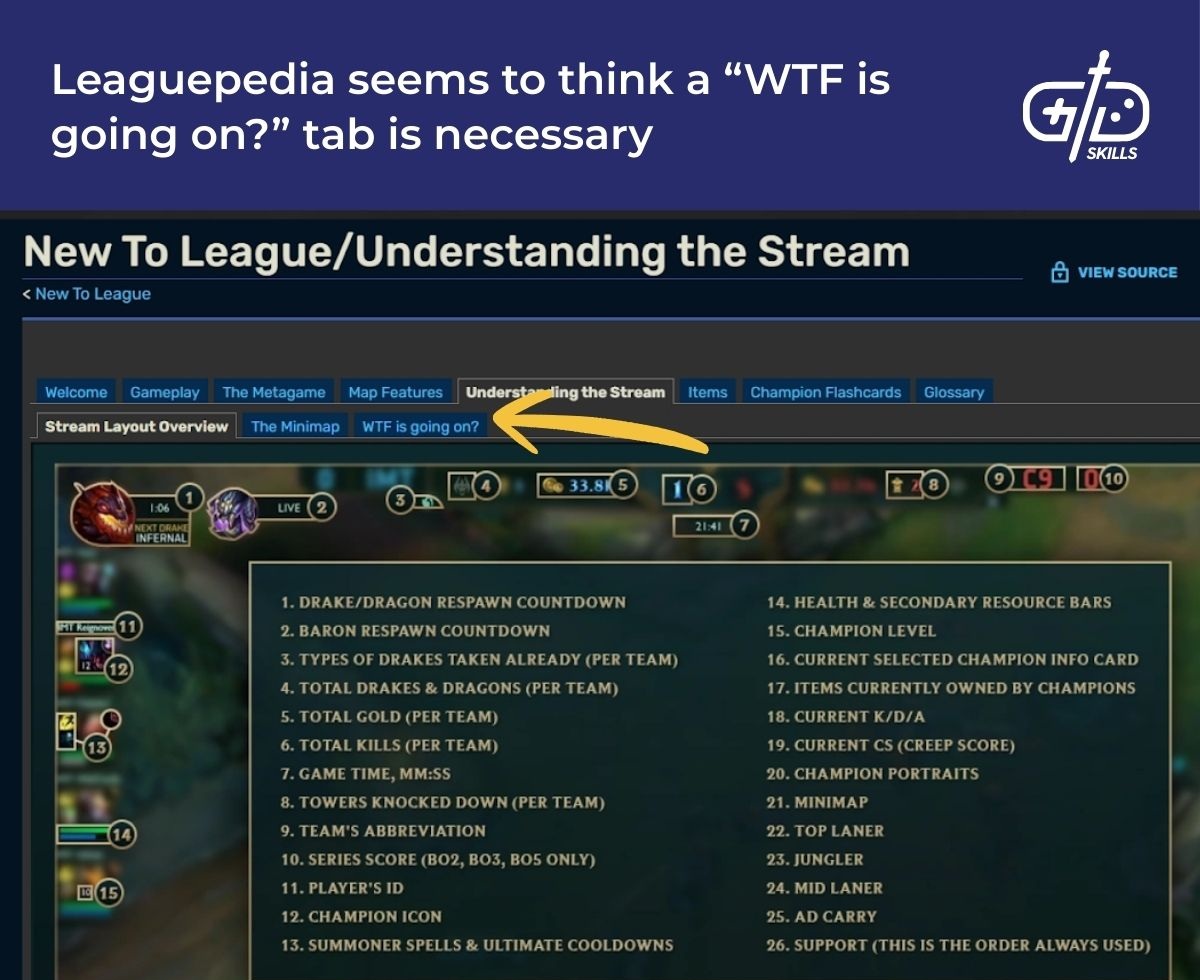

The fundamentals of MOBA game design are strategic gameplay, team-based competition, and a consistency that makes that strategy and teamwork possible. The moment-to-moment gameplay isn’t totally straightforward, as even knowing which team is winning requires knowing how many deaths the team has, how much gold they’ve earned, how many towers they’ve destroyed, and the number of NPCs they’ve killed. Consistency between MOBAs and visual clarity alleviate the issues with onboarding that these complex games have.

A MOBA is a team PvP experience, which means it comes with the following special challenges.

- Balancing a large cast of characters so there aren’t clearly effective and ineffective champions

- Making a champion not only fun to play but fun to play against

- Onboarding new players when much of the community is very skilled and the game is complicated to learn

PvP games have the potential to be intimidating and frustrating to newcomers, which is a crucial challenge for MOBAs to overcome. Players put many skills into practice during a match. Each player must choose from a selection of over 100 champions, know how to communicate with their team by pinging, understand the different roles for each champion in a match, and then decide what abilities and items to invest in as the match continues. This is without mentioning the jargon that comes with playing a MOBA, like last-hitting, poking, ADC, and jungling, that’s likely to be unfamiliar to new players.

The popularity of MOBAs as an esport gives them a reputation for sweaty competition and makes them even more intimidating. The player pool is a mixture of players who just want a fun distraction and those who take the game very seriously. After all, top players have a real chance of earning money by playing for a competitive team.

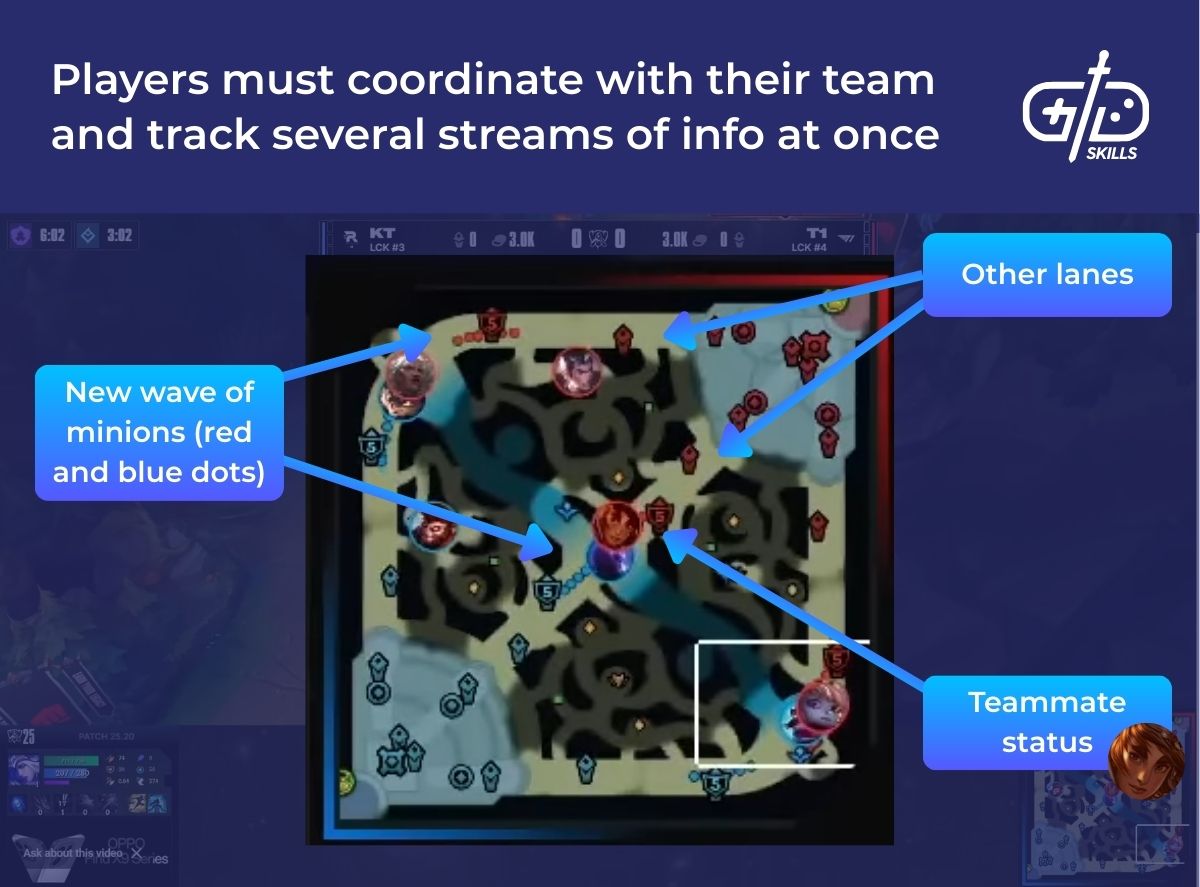

The fact that the PvP is team-based adds another level of potential frustration for players who’ve surmounted the learning curve. The objectives are simply too many for one player to carry. In a shooter deathmatch, there’s one objective – kill the enemy. In a MOBA, each match has three lanes to push down, five enemy champions, computer-controlled enemies scattered around the map, and high-value objectives to keep an eye on. Victory requires players to use their champions effectively and work together to break down the enemy’s position.

Poor teamwork is even more frustrating because the team that gets ahead usually stays ahead in a MOBA. Champions increase in power as a result of victory, giving them an advantage over the other team. Each neutral enemy and opponent defeated brings in gold and XP, which unlock powerful items, better stats, and new tiers of abilities. Victory is a positive feedback loop, where winning gives the team more power which makes winning even easier. If the enemy team makes a mistake, there’s a chance to catch back up, but a highly skilled enemy team is unlikely to make a mistake and the match is effectively over a long time before the actual defeat.

A MOBA designer has their work cut out for them: they must manage the frustrations and create a strategic, engaging experience out of the complex, team-based gameplay. Clarity is one guiding principle to start with when working to bridge the gap. Clarity means paring down the UI and game field so the player receives only the most relevant information. Combat must be as readable as possible. Animations, VFX, and sound work together to make sure that the moment when an attack comes out, does damage, and ends are each very clear to players.

Clarity also means giving players clear methods for learning the game. Tutorials, matches against bots, and watching high-level players stream are all valid ways for learning new strategies and getting better at the game in low-pressure environments.

A full description of how a MOBA communicates the game state needs to wait for an understanding of the mechanics. The fact that MOBAs have dozens or even over a hundred champions with different ability sets complicates the situation. The genre also has many preset roles that players need to learn before getting into a match.

What mechanics are used in MOBA game design?

The mechanics used in MOBA game design are centered around combat, intelligence-gathering, and boosting the power of their playable champion. MOBAs are strategic games, so much more than combat ability goes into the mechanics. Skillful movement and ability usage in combat is the core around which the other mechanics build. Managing the fog of war with wards, engaging with the jungle to gain gold, and leveling up over the course of the match are crucial components to consider too.

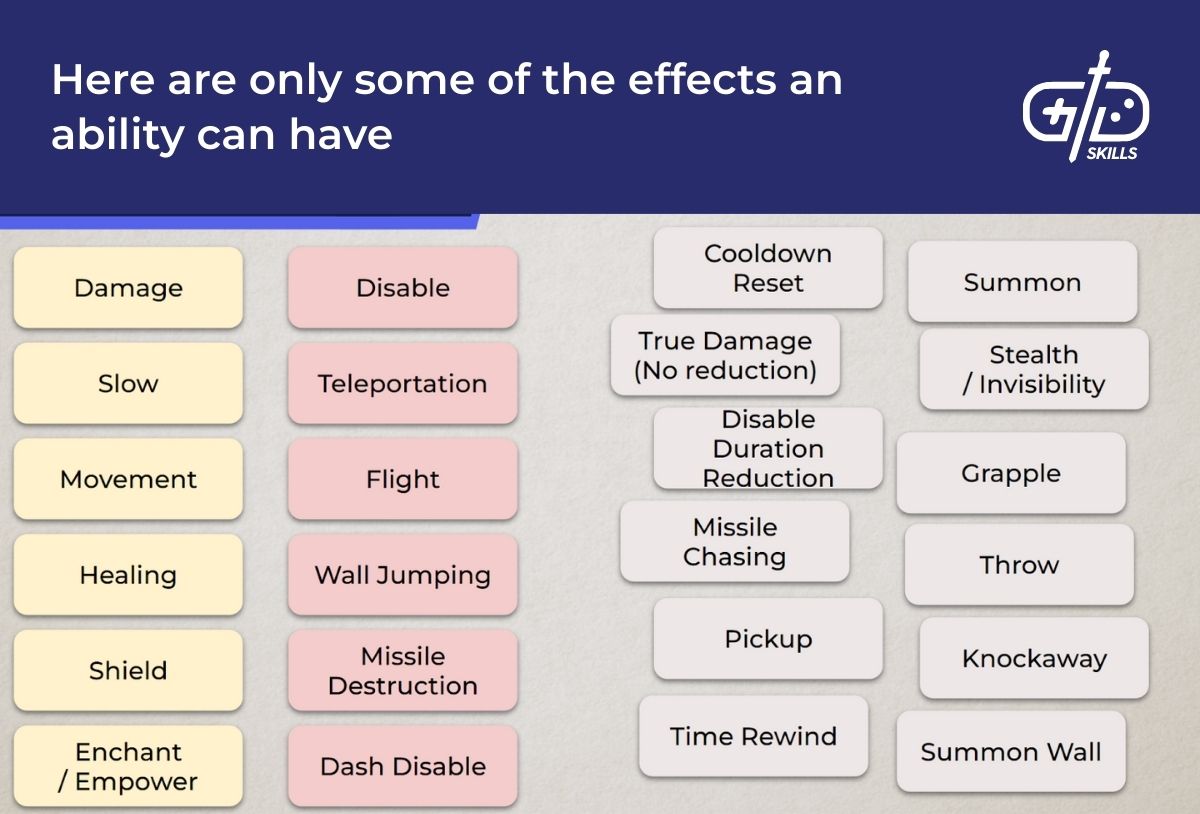

Players in MOBAs engage in combat largely through their set of abilities. The player has a choice of hero at the beginning of each match, and each hero has a role, or series of roles, that are defined by what abilities they have access to. There are too many mechanics to list all of them, but some deal damage, others stun enemies, debuff them, or buff your champion. The standard number of abilities is four, usually named after the key they’re mapped to: Q, W, E, and R. The R is the ultimate, often the most powerful ability, which is locked until later in the match.

The interaction of abilities creates a rhythm of play for each champion. A buff and a stun sets up the perfect circumstances to use an ultimate, or the same buff gives the player wiggle room to escape. To take the champion Garen as an example, his spin attack on E is already deadly enough, but has the bonus effect of silencing the enemy (that is, preventing them from using abilities or items). His Q ability increases his movement speed, so attacking, hitting Q, then E sets him up to attack a helpless victim and escape from attack range with the speed buff.

Much like an RTS, players control their character from above and click where they want them to go. Movement control is a crucial skill for success in combat, since being able to disengage is as important for survival as knowing when to join the battle. League of Legends differentiates a right click, which simply moves the champion to a location, from an A + left-click, which tells the champion to attack the nearest or selected target.

The setup is simple but results in a lot of nuance. The way players click and how they chain actions changes their survivability in a fight, as most offensive abilities in the game are skillshots. In other words, abilities require manual aiming and don’t track the target. Tying both attack and movement to the mouse buttons makes simultaneously dodging and attacking a test of skill. Top level players know to keep the mouse close to their player avatar, hover it to the side for quick dodges, and switch between left and right clicking when escaping to get some pot shots off.

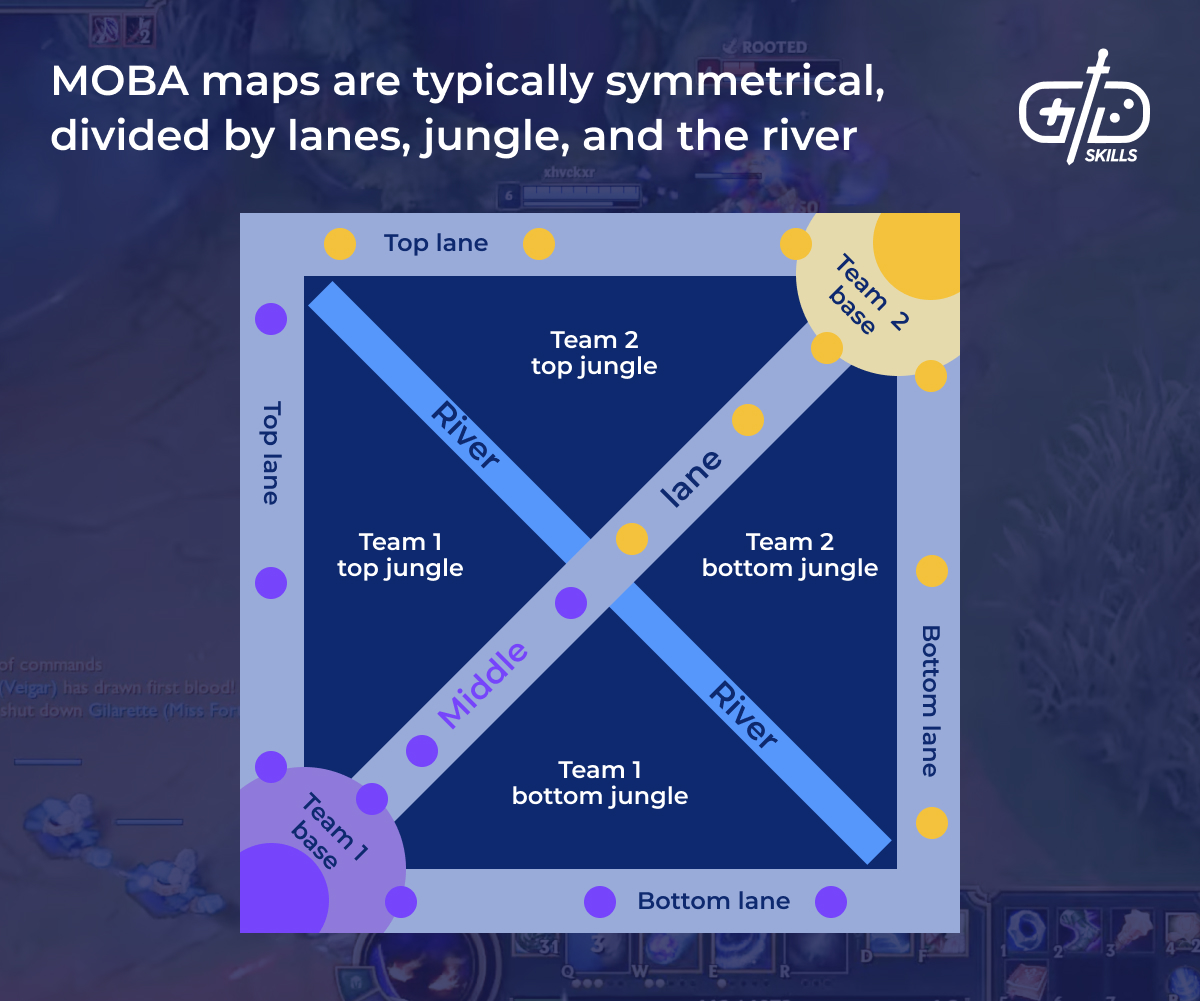

The map layout these battles take place in is consistent across MOBAs. The map has three lanes: top, mid, and bot (short for “bottom”). The lanes feature the biggest obstacles between the team and victory. Lanes have defenses along them including turrets and minions that prevent players from accessing their opponent’s base. The area between lanes is a labyrinthine zone called the jungle, which includes side objectives. Most MOBAs have a single map, as DotA 2 does, although Heroes of the Storm breaks the mold with a selection of maps and objectives.

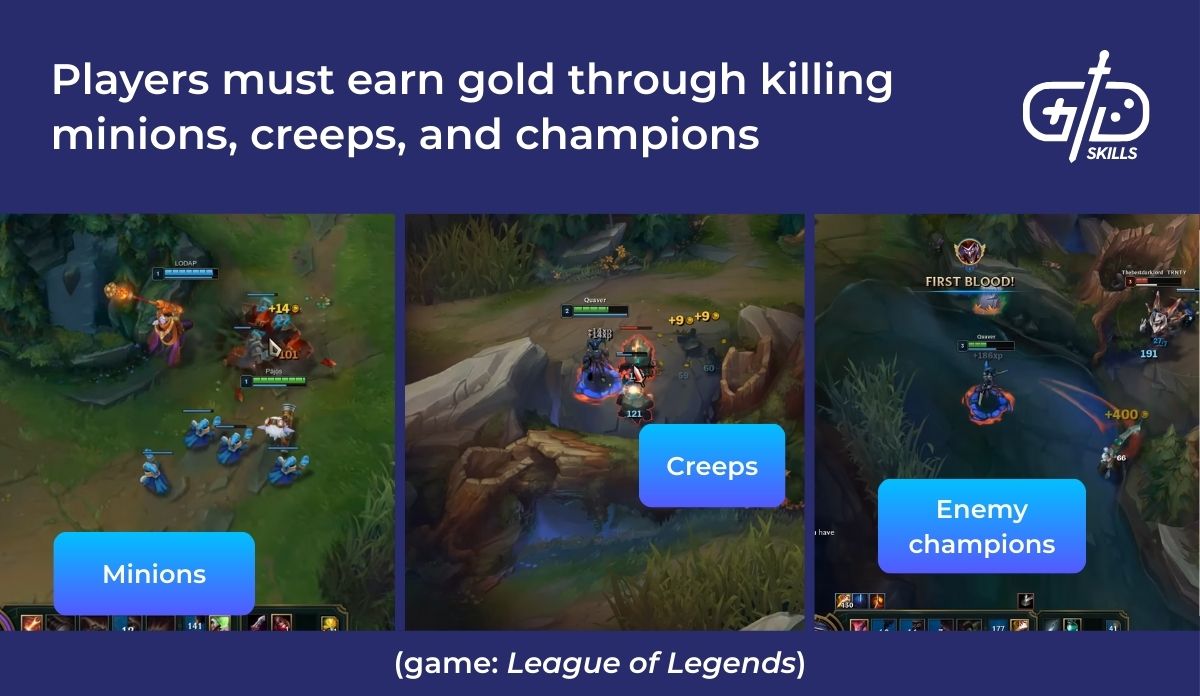

Each team also has Minions which come from their base and march down lanes attacking defenses and enemy players. Minions are an important component because they’re a source of gold and XP for players who kill them. Players outside of the lanes instead have the option to fight neutral creeps and other powerful NPCs for team buffs, XP, or gold.

The jungle is a maze-like zone which gives players the opportunity to escape or to ambush their opponents. The numerous hiding spots and levels of terrain open up opportunities for players to interact with their environment. The jungle in Dota 2 is split up by trees, which in most circumstances represent an unsurpassable barrier. Gankers such as Pudge and Nyx Assassin specialize in ambushing champions between these trees. Champions like Timbersaw or purchasible items such as Tango offer even more control over the map: they destroy trees and effectively reshape the map for a quick escape.

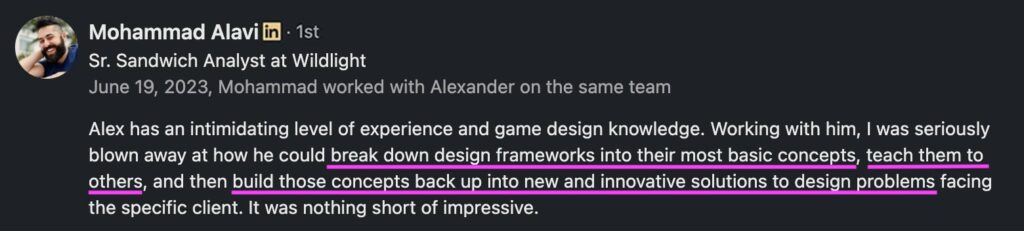

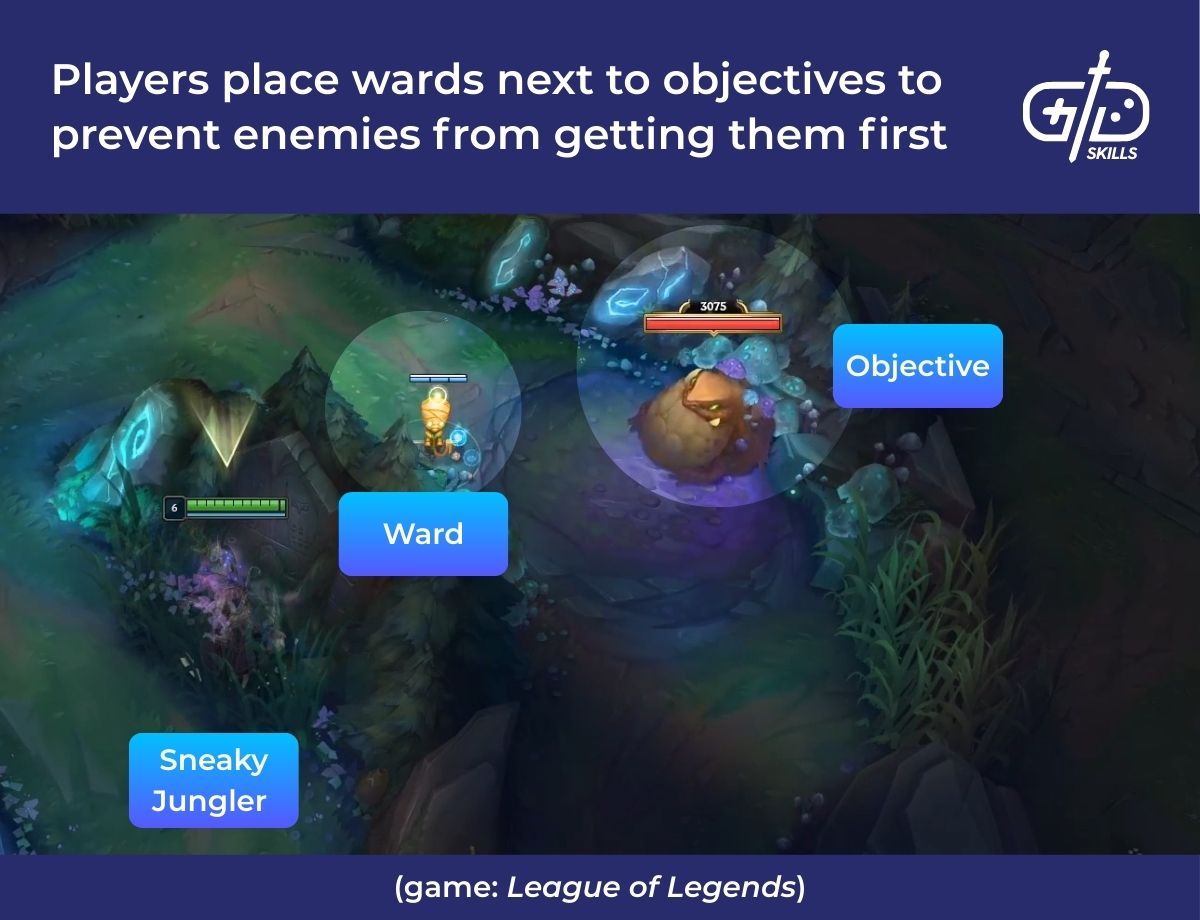

The fog of war obscuring unseen parts of the map limits the player’s ability to decide when and where to attack. The fog of war acts like it does in an RTS. Areas outside of their team’s line of sight are darkened and enemy movements in the fog of war are invisible. Players must manage fog of war to avoid ambushes and make sure enemies don’t steal an objective. Some champions are able to create wards which grant sight around them, so teams have to choose where to place wards and heroes to get vision on crucial areas of the map.

Players upgrade their character over the course of a match through buying items and leveling up their abilities with XP. Leveling up lets players rank up abilities or unlock their ultimate. Items in the shop are a challenge for players because they add another system to learn on top of abilities, game rules, and leveling up. For this reason, more beginner-friendly MOBAs like Heroes of the Storm do without the item store. Items in MOBAs that do include them tend to come with basic buffs to movement, damage, health, regeneration, resistances, and any other hero statistics.

The gold and XP motivate players to strategize. Computer controlled enemies, whether minions in lanes or creeps in the jungle, provide XP and gold on defeat. The match doesn’t just come down to skill in PvP combat as a result. A team that more effectively farms NPCs gains power quicker and therefore an advantage earlier.

How to design characters for a MOBA game?

To design characters for a MOBA, have a clear role in mind for the champion. Each champion has a specific lane they’re most effective in, or a type of combat they specialize in (ranged, melee, magic). What this role looks like in practice is determined largely by the character’s kit, which is the set of abilities available to them.

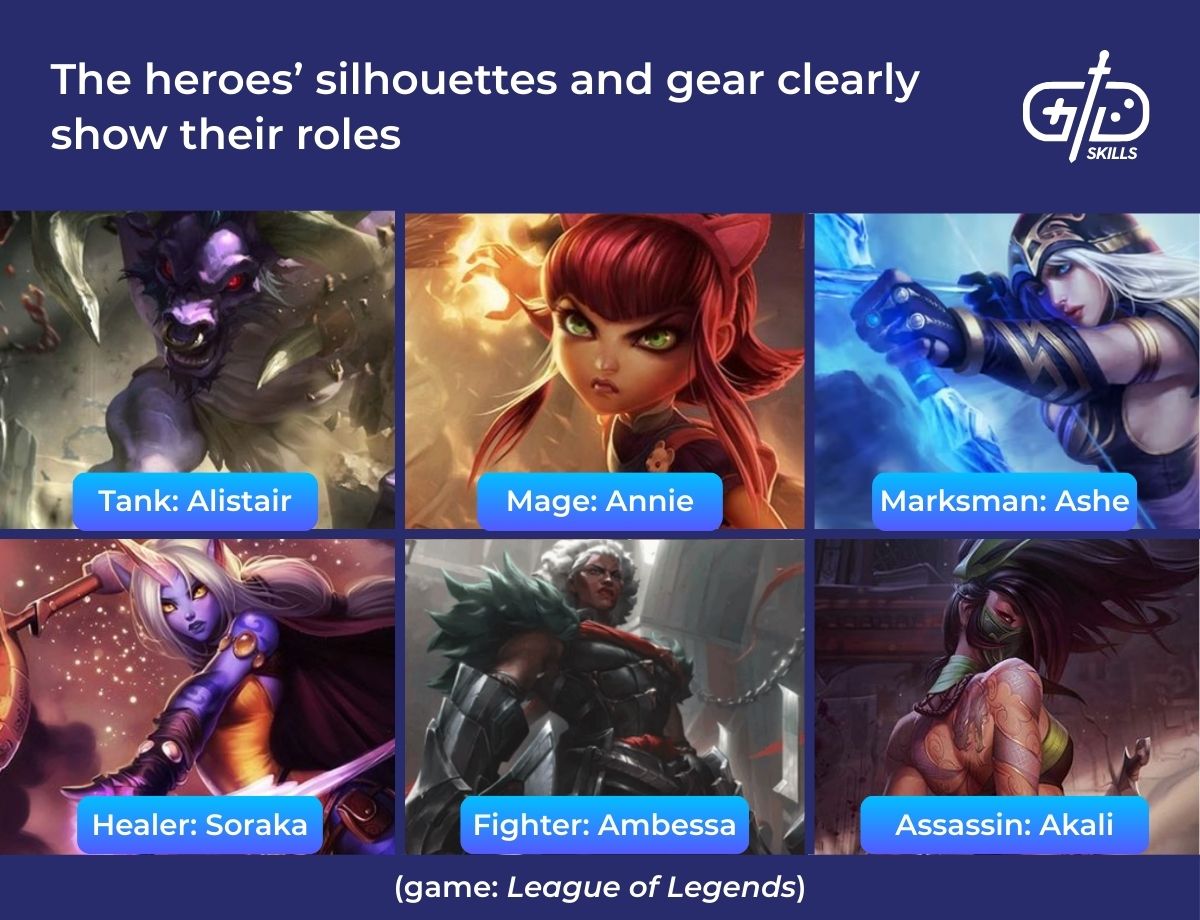

The basic roles are a tank, mage, marksman, healer, assassin, and fighter. MOBAs have dozens or over even a hundred characters, so roles often intersect. Urgot, for example, is a tank but also a marksman, an unusual combination.

MOBAs have genre-specific roles as well which respond to their lane-based map design. The specific roles vary from MOBA to MOBA, but the concept of a jungler and a support is fairly common. A jungler, named after the fact they work best in the jungle, is effective at clearing out creeps and ambushing players. Focusing attention on gaining gold and XP in the jungle leaves more resources for the champions in their own lanes without having to share. Having an extra champion in play anywhere also makes for a strategic advantage if another hero needs help. The support helps other champions by buffing them or joining team fights. In League of Legends, they tend to stick in bot lane so they’re able to support the other champion there.

Champions are often categorized by which lane they’re most effective in. League of Legends and Dota 2 both have solidified the idea of a flexible mid-laner, a powerful, solo off lane champion, and a Carry who takes the last lane with the help of support. The Carry needs support because they’re a weak hero in the early game, but, with enough gold and XP, they become very powerful. In League of Legends, the five roles on the team are called Top Lane, Mid Lane, ADC (Carry), Jungler, and Support. With these preset roles, players know where they’re expected to go and how they’ll contribute to team victory. Dota 2 has similar roles, but it reverses the placement for each team, with the top and bottom lanes each having a solo champion going against the Support/Carry pair.

Champion roles intersect, with position-based roles (top lane, jungler, etc.) mixing together with the traditional classes (tank, marksman, assassin); some heroes also switch roles depending on how they’re played. Xerath, for example, is a mage just as Zyra is, but the role they fill in the game is different. Xerath has the potential to deal a lot of damage at long range, so he does well both in mid lane and as a support in the bottom lane. Zyra works well as a support because of her crowd control abilities, but her pets and high damage also work well for clearing the jungle.

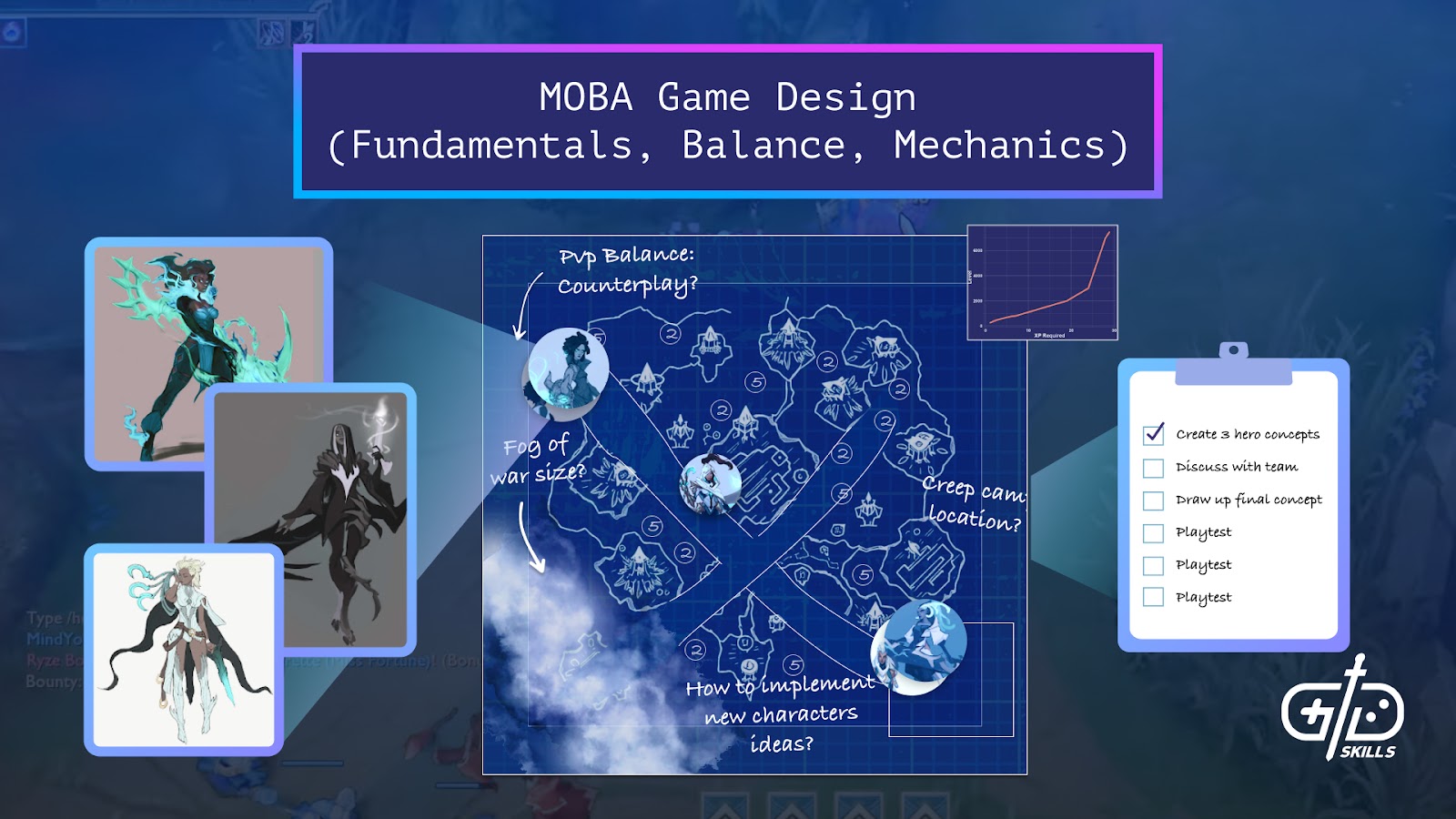

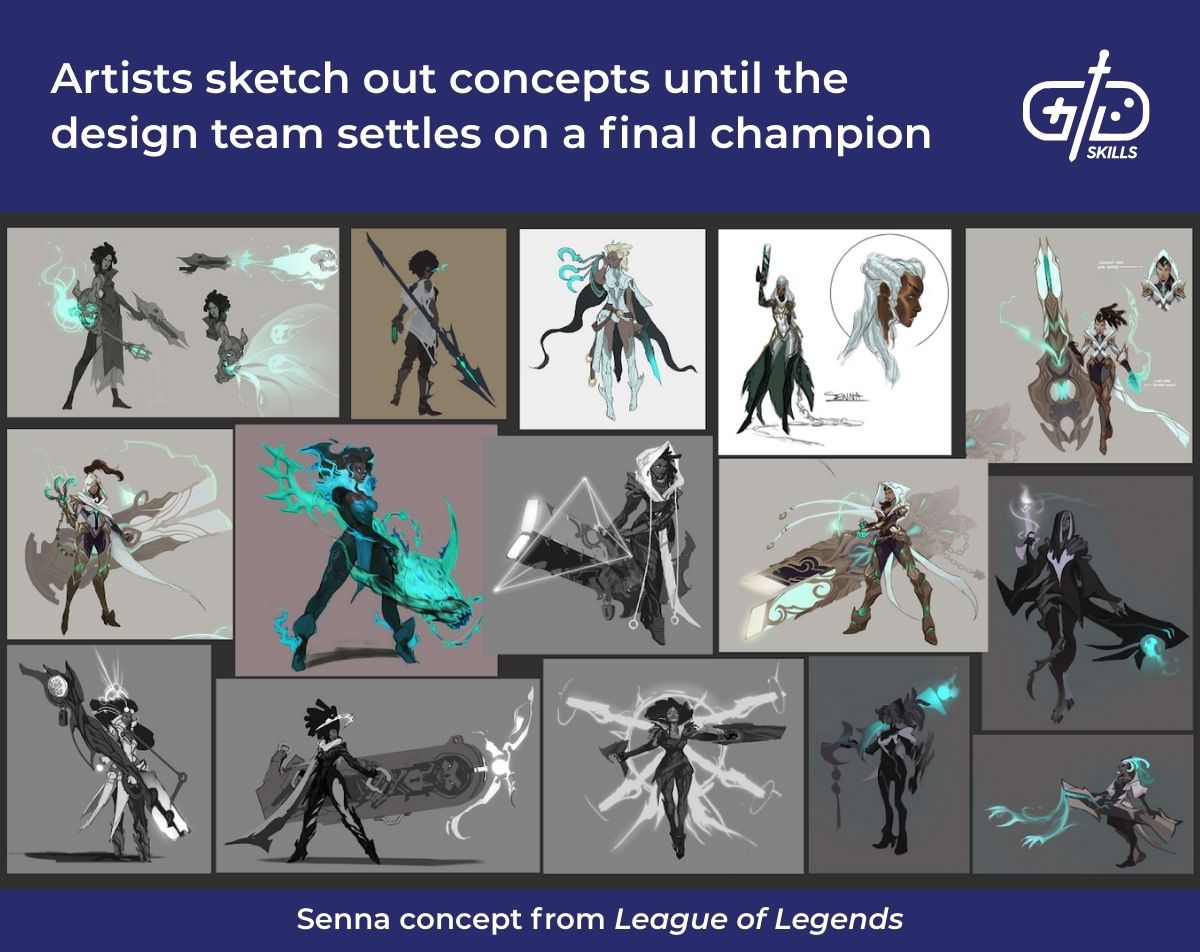

When I worked with Riot, the creation process for a champion went through several stages of ideation, experimentation, playtesting, and polish. Creating a new character often starts with one of these roles or even just a new concept. The team considers how long it’s been since a jungler has been added to the roster, or whether it’s been too long since a monster-type champion has joined the ranks. The narrative team and concept artists then narrow down to three concepts, which they build a second round of concepts on before making a final selection.

The champion designers at this point take multiple concepts internally, playing around with mockups of different ideas — all very rough. When a kit (or set of abilities) starts to come together, multiple designers work together to help the point designer, who is ultimately responsible for that champion until release, refine the idea until it has both gameplay and conceptual polish.

The visual design for a champion needs a distinct silhouette that makes them easily identifiable in the battlefield and also sells what that champion is about. The silhouette features the major source of their power. A major feature of Senna’s silhouette is her gun; the most identifiable part of Graves, his shotgun, is the primary source of his strength. When the silhouette isn’t clear enough to show the champion’s strength, distinct animations help sell the silhouette.

The artists in the early stage put in a rough model with simple block-out animations for the designers. All of the VFX are copied from other characters, and it’s frankly a huge mess! Until the gameplay gets locked in, the animators, vfx artists and technical designer work together to refine the concept.

The timeline for character design varies, as any number of unpredictable events has the potential to push back release. Champions usually have a target date, but sometimes you find showstoppers. While the champion goes into a few months of lane and teamfight testing, balance issues have the potential to crop up. Azir was redone multiple times, Xerath’s ult changed to a simplified ICBM only a few weeks before release, and sometimes champions will even be revised after launching. That’s okay though, as it’s all part of the process. Just know that there’s less and less flexibility the longer the cycle goes.

How to design essential elements of MOBA games?

To design the essential elements of MOBAs, look to other MOBAs like League of Legends for inspiration. The basic layout of a map and the elements in it are universal. A map consists of a base at either end, lanes between the two bases, and defensive towers along the lanes. The objective is to destroy the enemy base, but the team also worries about defending their own lanes and earning gold through optional objectives. The way players earn gold and bust defenses is what alters the pacing of a match and sets your MOBA apart.

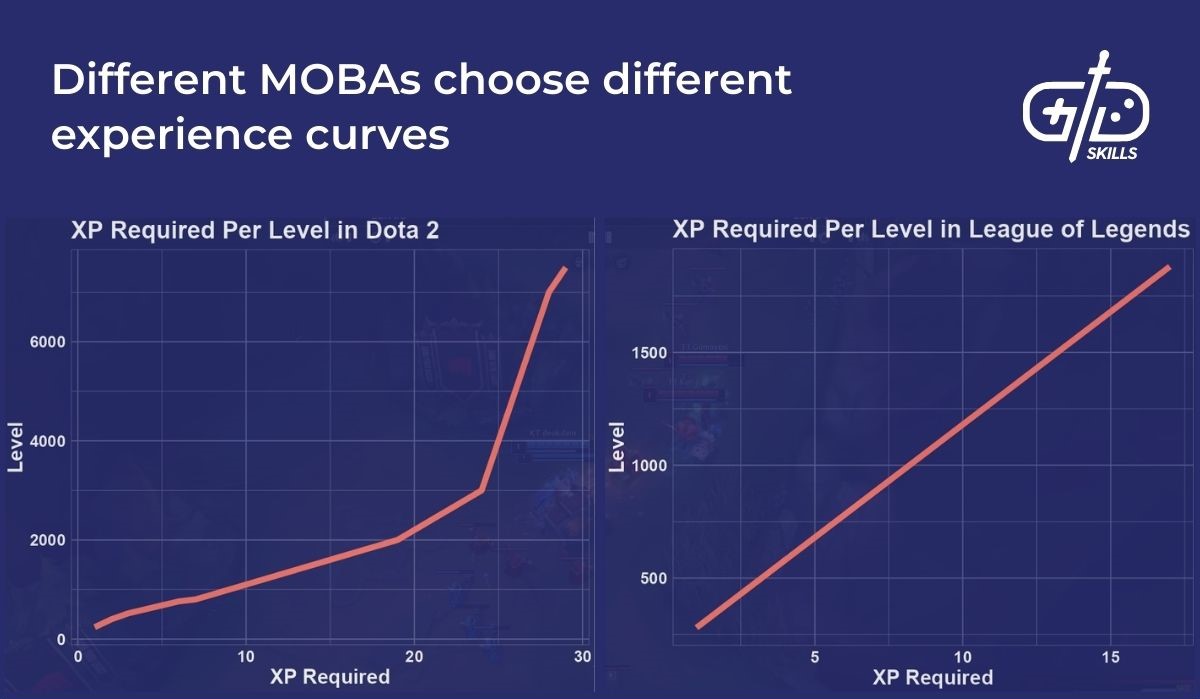

A MOBA match starts out at lower intensity and builds up as characters level up and wear down the enemy’s defenses. Players earn two resources regularly through playing the game, gold and XP. XP directly increases the power of player abilities and also unlocks ultimate abilities as champions progress through the match. The ultimate tends to unlock at specific level breaks: in the case of LoL, it becomes available at level 6 and upgradeable at 11 and 16. Players supplement these increases with items from the shop, which apply additional buffs and cost gold to purchase.

XP tends to have specific limitations in MOBA games. XP is only earned by killing enemies. The player doesn’t even have to be directly involved in killing the enemy, as they earn XP for standing nearby when death occurs. Once the player has earned XP, MOBAs limit how many points the player’s able to spend on one ability in a row as well (e.g. not being allowed to spend more than half their level ups on one ability).

Most MOBAs have one map, but Heroes of the Storm experiments with multiple maps, which makes it an appropriate model for looking at how to differentiate maps in a MOBA. Each map experiments with different objectives that force the team to leave or focus certain lanes to achieve victory. Warhead Junction spawns nukes at intervals around the map, which are items that players have the option to activate for massive damage, especially around enemy structures. The Towers of Doom spawns an altar periodically at set locations around the map, and the team that captures them causes bell towers to fire on the enemy core, the only way to achieve the victory condition on this map.

The fog of war covers all areas of the map not covered by members of the player’s team or other vision-granting units like minions, towers, turrets, and the player’s base itself. The vision around each unit is usually smallest for wards, as they’re the most flexible in their placement, while champions reveal the largest segment. League of Legends has only four tiers of vision. The lowest is 500 units for Farsight wards, 900 for other ward types, 1200 for ordinary minions, and 1350 for champions. Dota 2 adds variety to the system through its day/night cycle, which decreases vision granted for everything at night, although some wards still keep their daytime vision radius.

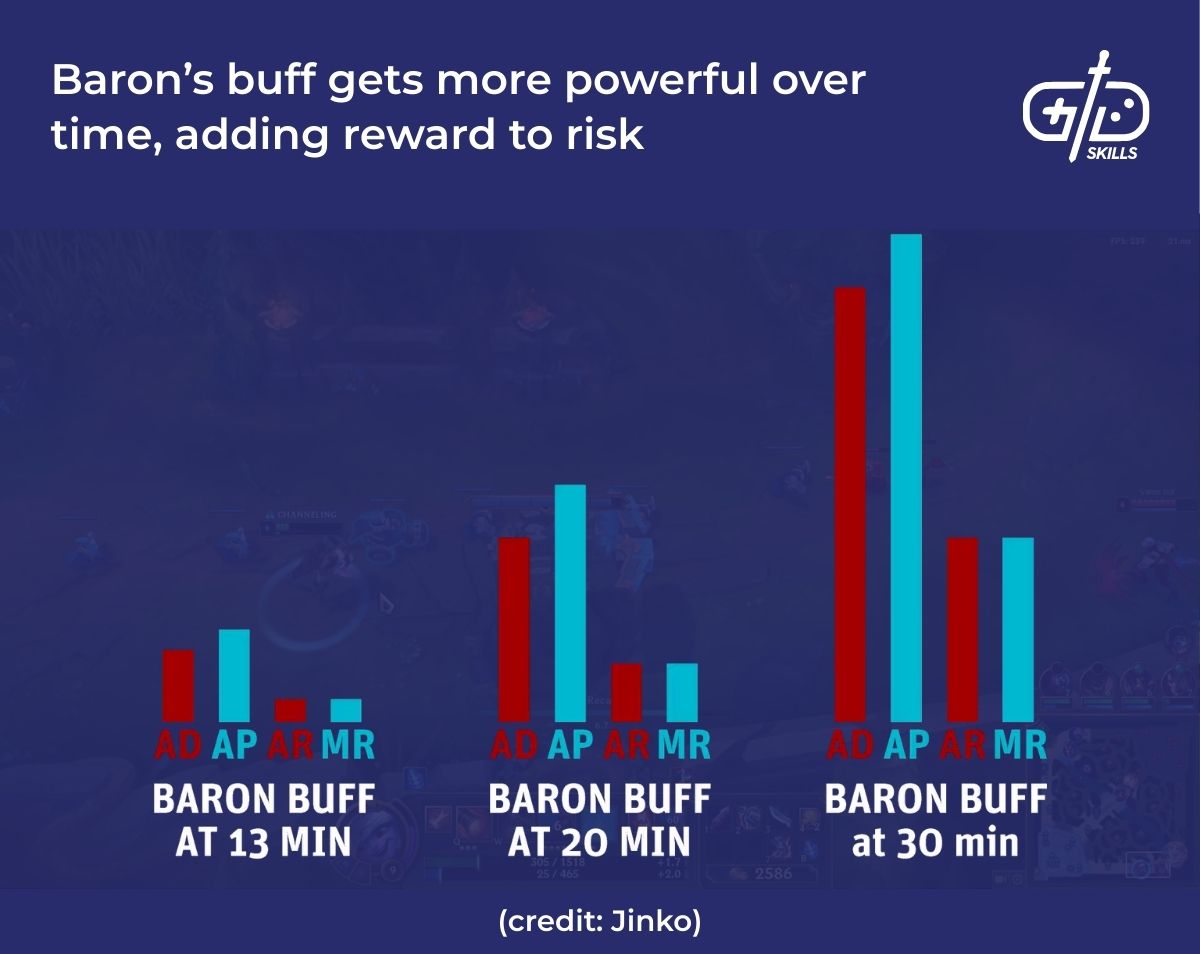

Objectives need to appear at regular intervals throughout the match to encourage players to wander from their lane and engage in player battles with high stakes. Objectives in League of Legends are usually monsters in the jungle. These monsters spawn on preset timers which start as soon as the camp is cleared.

Epic monsters like Drakes and Baron Nashor in League grant special buffs to the whole team on kill, making them a valuable target when they spawn. Drakes spawn at five minute intervals, although no new drakes spawn if the old one is still present. Baron Nashor is the most powerful neutral monster, and he only spawns at 25 minutes. Killing Baron earns the team a huge buff which increases the longer Baron has been alive.

How to design economy in MOBA games?

Design the in-match and premium item economy in MOBA games to ensure matches remain engaging for everyone. The economy has two distinct meanings for a free-to-play MOBA: the cost of utility items in the game, and the cost of in-app purchases for cosmetics, boosters, and champions. The latter of these two systems I’ll always refer to as in-app purchases to keep them distinct. Designers ought to set a line between the two economies, because the tier of players that don’t pay money suffer when other players are able to pay for items that boost their power.

The in-game economy is based around earning gold. Players use gold to buy items in the shop, which provide useful new abilities, buffs, or utility items like wards, which reveal areas to player vision. All players earn a certain amount of gold passively in League and Dota 2, but players must take action in order to earn more gold than their opponents. Players have three options for earning gold actively: killing enemy players, killing neutral NPCs in the jungle (creeps), and killing minions.

The gold system encourages players to go after objectives and play strategically. The more gold players have, the more powerful items they have access to. Leaving powerful creeps to the enemy team doesn’t only reduce the gold the player has access to, but increases the income of the other team. Rather than rely on pure combat and tactical skill, the team must think ahead and keep an eye on major objectives to ensure they’re able to contest them.

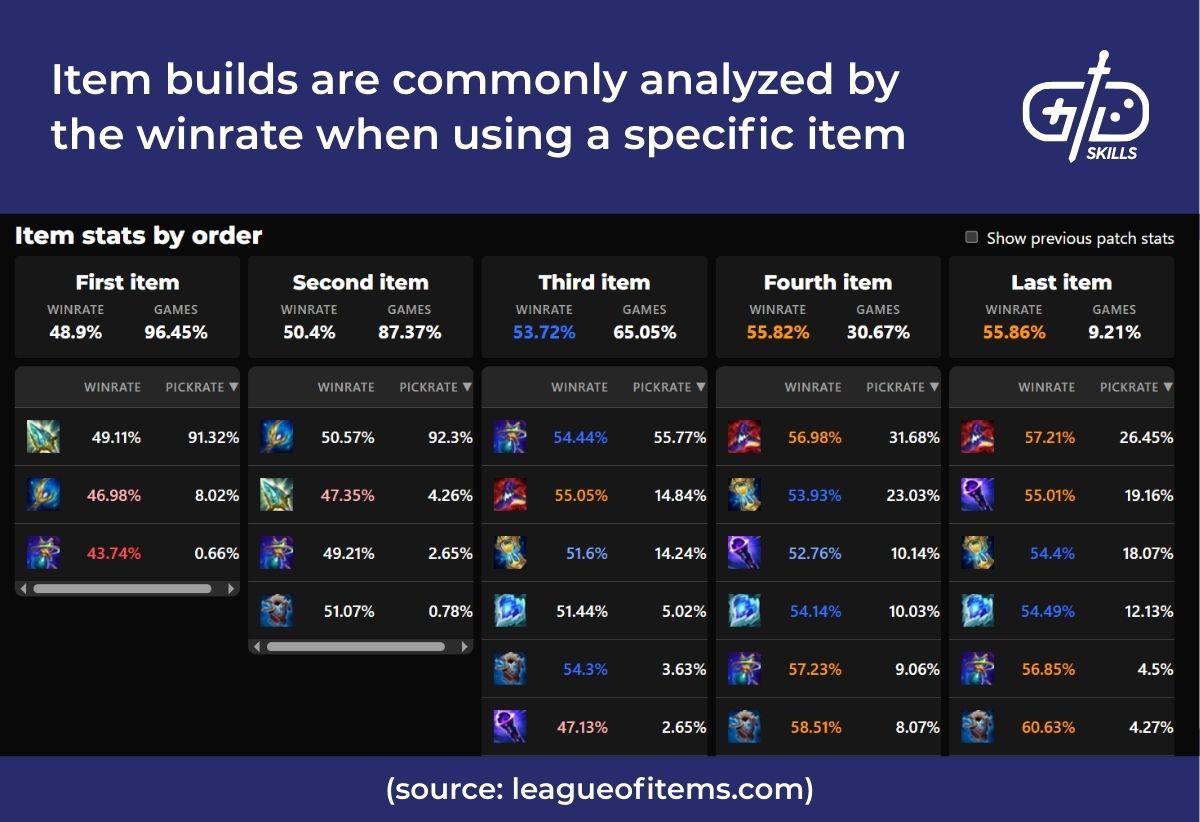

The cost of the items in the store is designed around types of builds. In League of Legends and Dota 2, these are builds consisting of 6 items, although Dota 2 players are able to store extra, inactive items in their backpack. The ideal build is generally balanced around the type of champion that uses it. An item build for Marksmen is the most expensive, while a build for support classes is the cheapest. To take a specific case, an ideal build for the ranged champion Jinx costs about 20,000 gold total, whereas an ideal build for the support Seraphine is around 13,000. Otherwise, the general principle is that tier 2 items are 50% more expensive than the base, beginner items.

In-app purchases are for the most part restricted to cosmetics such as skins and emotes to ensure gameplay is fair for paying and non-paying players. League of Legends does sell champions, but there are a few systems in place to make sure the shop is fair. Champions have two costs. The first price is in Blue Essence, which is the currency players earn just through playing the game, and the second is in Riot Points, which are the premium currency. Any champion (or XP booster) is earnable through gameplay alone via Blue Essence. Additionally, Riot has a weekly rotation of 20 champions that are free to use, so no champions are closed off to the free tier of players.

Champions are priced according to when they were released and how difficult they are to learn. Riot Games discusses the pricing of champions further in their digital content FAQs. The most expensive tier of champions is reserved for ones that have been out for two seasons or fewer (typically 8 months). After that, Riot sorts champions into 6 tiers, with more expensive champions being harder to master and the cheapest tiers being the most beginner-friendly.

How to design a UI for a MOBA game?

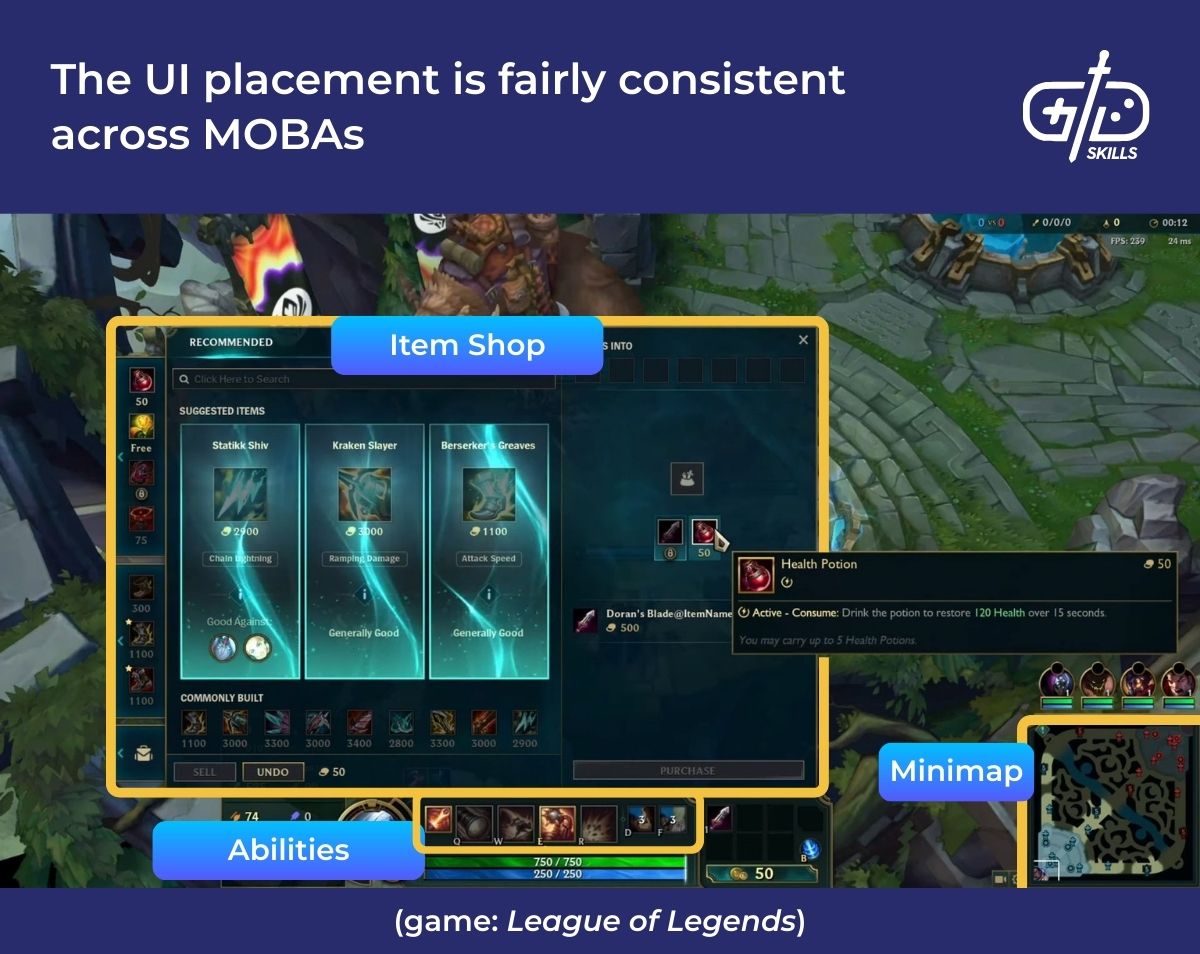

Design a UI for a MOBA that’s consistent with the features players expect from the genre. A MOBA needs clarity, and players have deeply ingrained expectations about how to access information. The minimap, abilities bar, and inventory are core components of the genre, just like the QWER mapping is for abilities. The game UI must be as clear and simple as possible otherwise to manage the player’s cognitive load.

A HUD in a MOBA has the following core components.

- Minimap

- Abilities

- Inventory

- Character stats

- Store

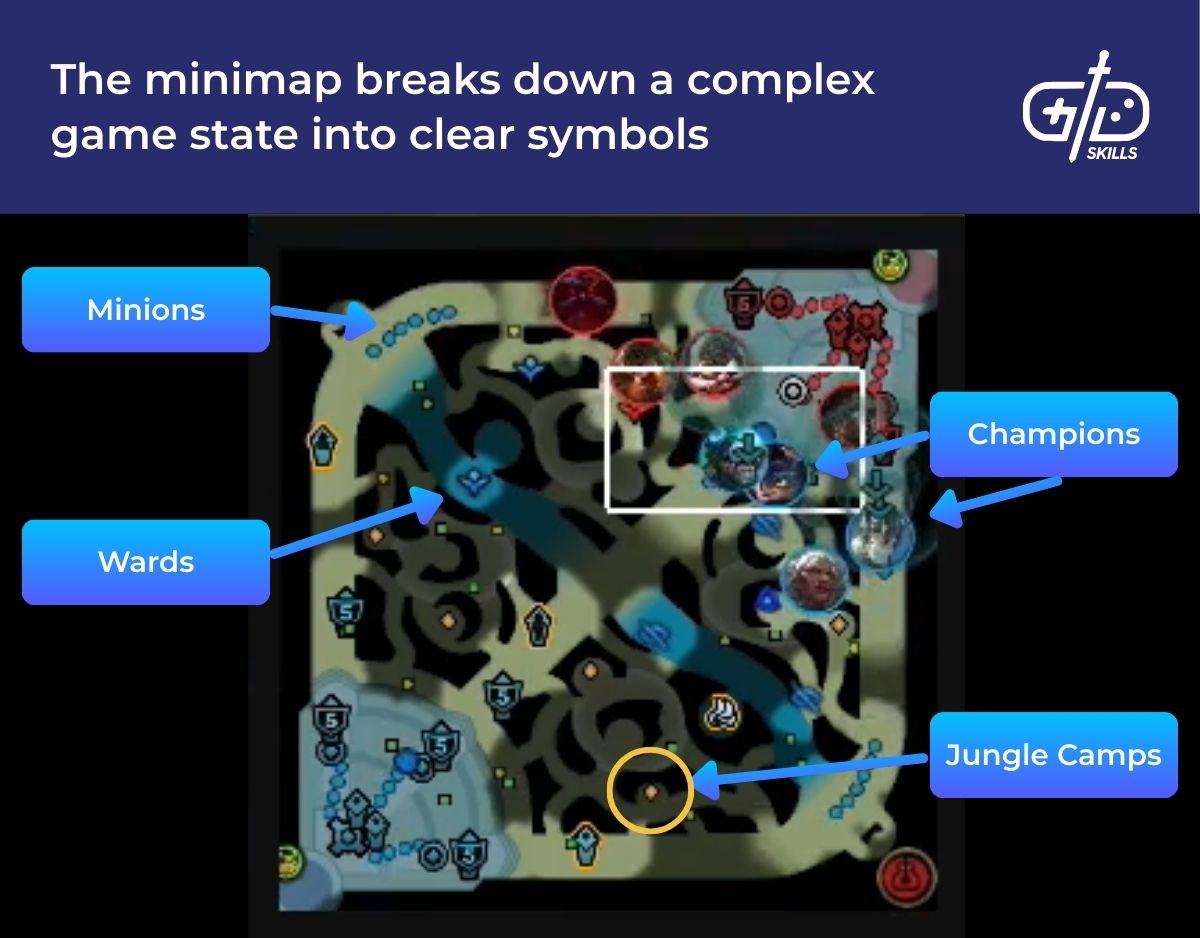

The minimap has its place in managing the player’s cognitive load. The concept of cognitive load comes from education, and it refers to the max number of pieces of information the brain is able to manage at once. MOBAs put a great strain on cognitive load, requiring the player to think about teammates, objectives, abilities, shop items, and leveling up. A player who’s mastered a MOBA lowers their cognitive load, because the skill of managing these tasks is so ingrained they don’t even think about it, like when riding a bike or driving a car.

A consistent UI design lets these veterans go on auto-pilot, and they know from a quick glance at the minimap whether the next wave of minions is coming, which towers are still up, where teammates are, and whether enemies have entered visible sections of the map. Each champion is able to focus on only the information on the map that’s important for their role. A bot lane champion only cares about when new waves of minions are coming and where the other bot lane champions are, and the map helps them manage that information.

The bar at the bottom centers around the player’s abilities, matching the expectations set by previous generations of RTS games, action RPGs, and MMOs. The UI here is consistent with other genres, just like the minimap, so experienced players know exactly what they’re getting. The most important information to communicate here is the status of cooldowns. The solution is obvious, but not entirely trivial. An ability on cooldown typically turns dark and a cooldown swipe begins to tick down until the ability is ready to use again.

A subset of abilities have multiple cooldowns, which complicates the situation. For example, Darius’ W ability boosts the next auto attack he does in the next four seconds. The game needs a less subtle graphic to communicate this isn’t a cooldown where the player’s expected to wait, but where the player’s expected to act. The game uses a gold swipe around the edge of the ability’s icon to show how much time the player has to execute the move, before switching to a blue swipe over the whole icon to indicate the player must wait to use it again.

The inventory and character stats occupy the same section of the screen as the abilities. The only menus that cover the game screen are the shop, so players are free to look at their stats and manage their inventory without opening new menus. The inventory is simple, but its implementation does have an effect on gameplay. For example, in Dota 2, gaining charges which replenish an item is done giving priority to the top-leftmost item that needs it.

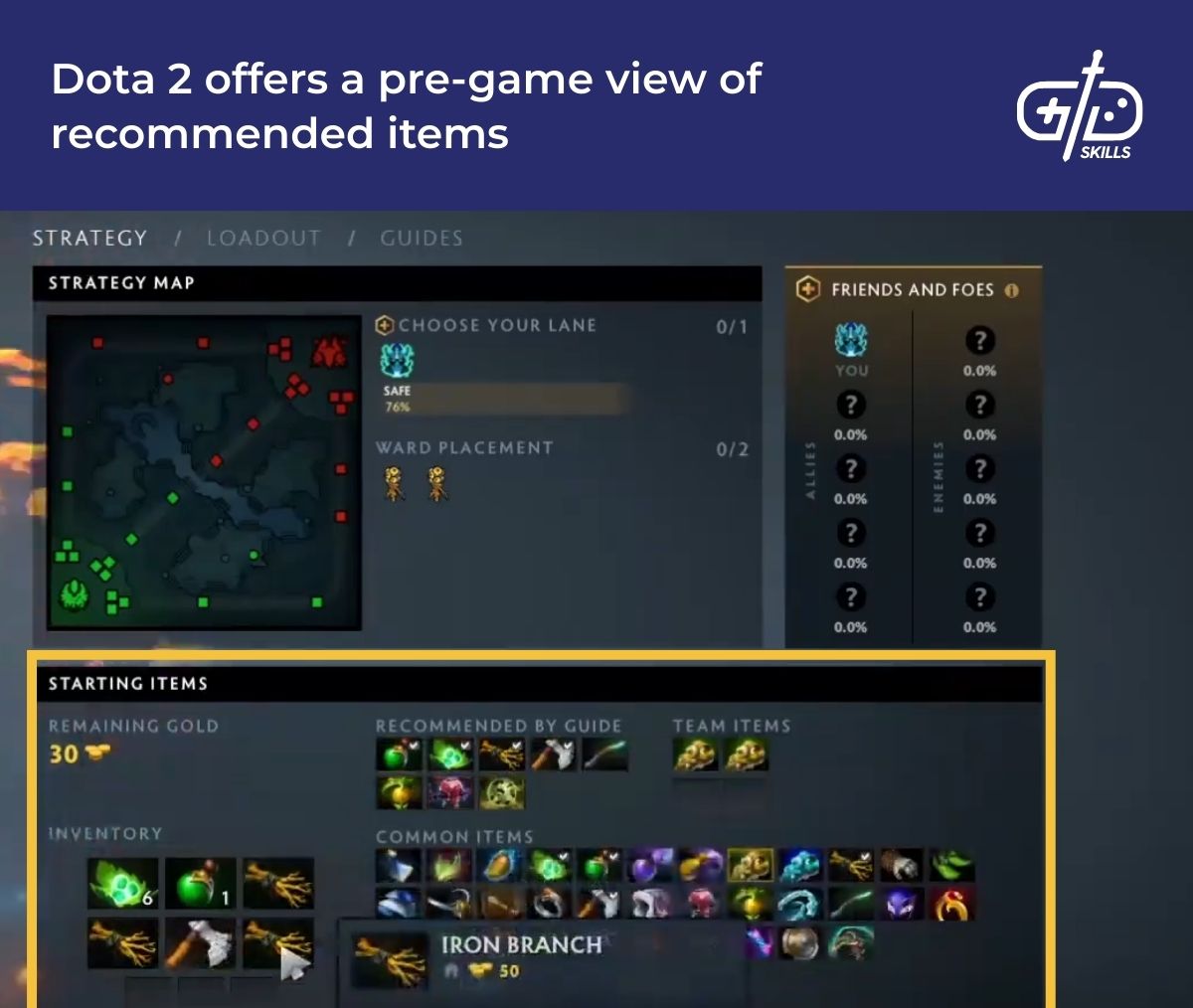

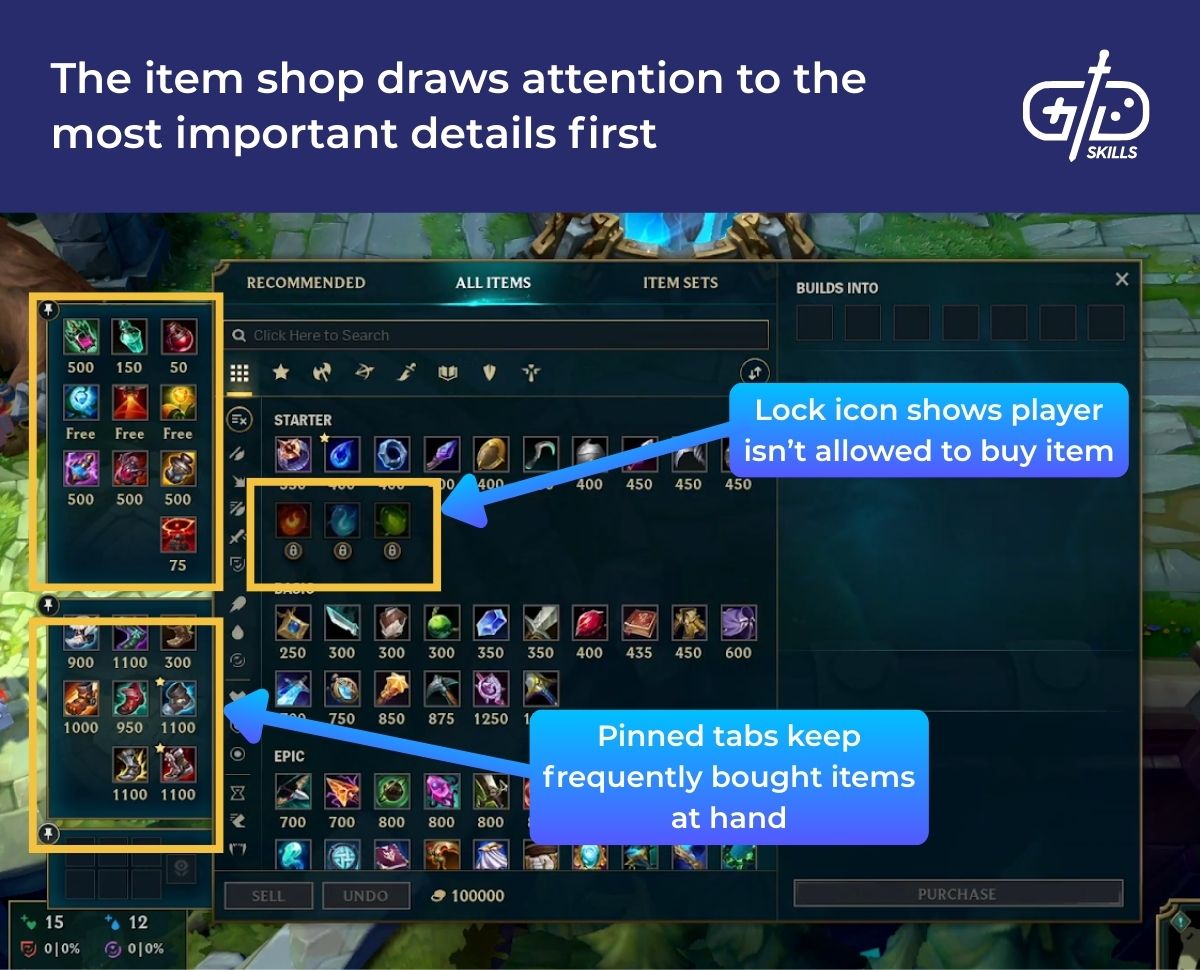

The Store interface includes several tabs and panels that help players manage their time. League of Legends has 306 items at the time of writing. This mass of items is too much to manage as a new player, so the shop tends to have a “Recommended” tab that filters down to only the items most beneficial for their champion or most useful against the heroes on the enemy team. Common consumable items also have their own tab that gives the player instant access to items they’ll need to refill frequently.

The shop uses symbols and shorthand to further narrow the player’s attention on the most relevant information. Graying out items players aren’t able to buy isn’t enough to help players make strategic decisions. Items are locked for more than one reason, whether because their champion isn’t able to afford the item, they don’t have the necessary components for it, or they already have too many items of that type. League of Legends grays out items the player doesn’t have enough gold for, but they use a lock icon to show the player doesn’t meet the item’s other requirements. That way, the players know at a glance what items are unavailable and why.

MOBAs rely on pinging systems to allow teammates to communicate without using voice or text chat. Pings place an icon on the map which sends a certain message to teammates. The ping usually sends out a chat or alert to other player’s that it’s been placed, and it shows up on the ground and on the minimap. Not every MOBA relies on pinging alone, but Smite also has its Voice-Guided System (VGS). Players hit a key combination to cause their player to say a certain message out loud. The system is much more complex, but each button press shows the options on the left side of the screen so they don’t have to memorize the combinations.

How to balance gameplay in MOBAs?

Balance gameplay in MOBAs by maximizing player agency through careful ability design. A balanced MOBA ensures the player has the tools they need to deal with disruptions. No opposing champions ought to do something the player has no way to deal with. On the same token, balance means keeping the game from getting too easy as well. There’s no single solution to balance, so a crucial component is having clear goals when making changes to a hero. Without a clear goal (making a champion more effective in the early game, increasing the win rate of a hero at the top level, etc.), there’s no way to know what to change nor to know whether the change succeeded.

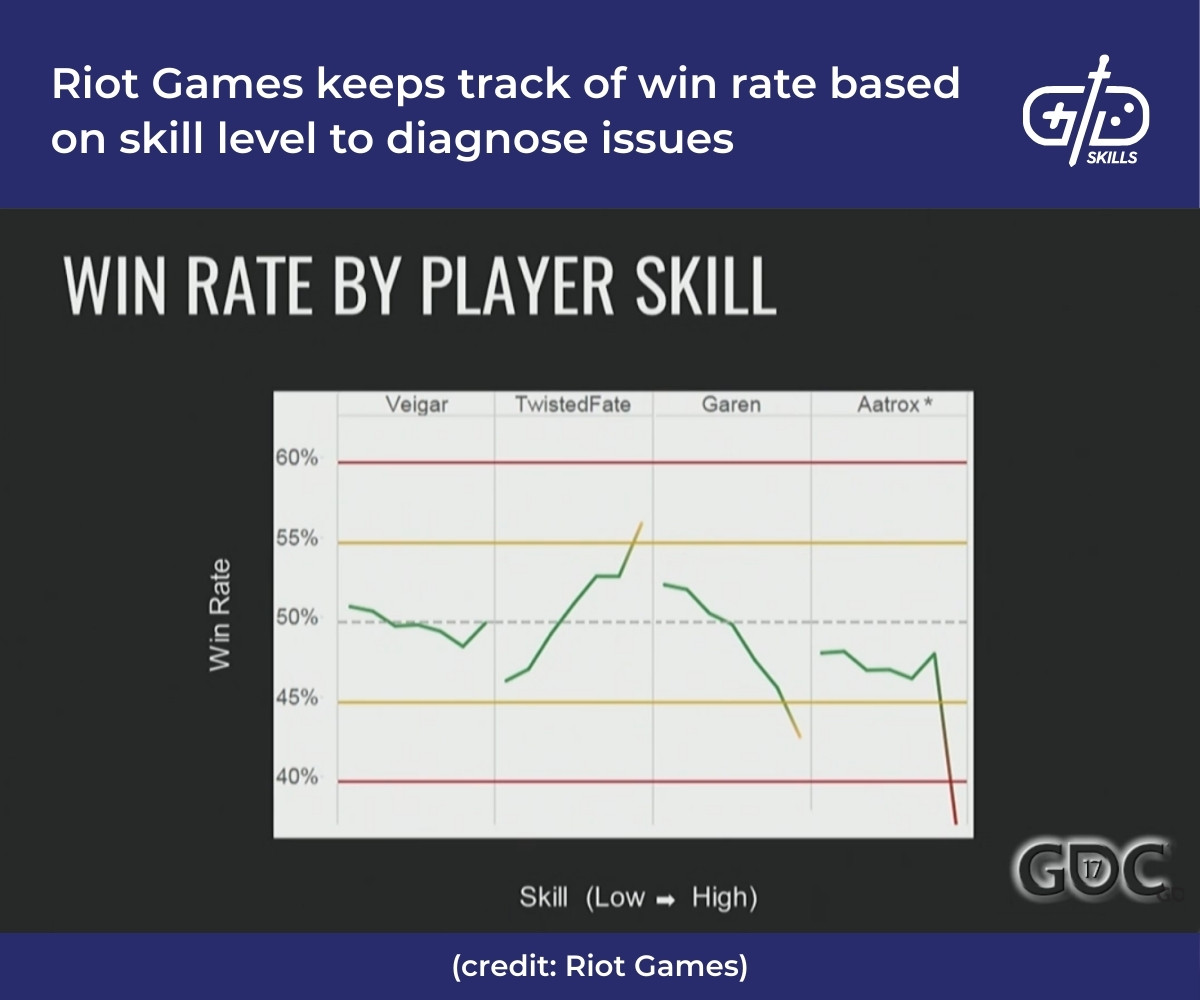

Data collection is therefore crucial for pinpointing these issues. Using the data correctly requires approaching it with a critical eye. For example, Riot targets a 50% win rate for all League champions at all skill levels. However, the global win rate for a champion isn’t enough to identify a problem, as the popularity of the player or the player’s experience is also going to affect the win rate. A player who played a champion five times and has a low win rate isn’t evidence of an issue; a low win rate after playing 50 times is.

Reaching out directly to the community is another option for making sensitive changes to champions. Any champion is possibly someone’s favorite, so any radical changes ought to align with what the current players enjoy about the champion. That’s not to say it’s possible to avoid stepping on everyone’s toes, but having an idea of what the core fantasy of a character is requires knowing what the community thinks. This solution comes with caveats, though. In my Blizzard days, I needed to keep my discussions with top players as secretive as possible, both because the company was restrictive on direct communication with the community and because the community didn’t completely trust the studio to handle a rework properly.

A key concept to balancing abilities for a MOBA is counterplay. An ability with counterplay is, intuitively, one an opponent’s able to counter. Counterplay is key for multiplayer: singleplayer experiences are allowed to cheat in the player’s favor, but competitive multiplayer must be fair to both sides. The question a designer ought to ask when creating the ability is, “Does using this ability open up options for the opponent, or shut them down?” Ideally, a player has choices when they see an enemy use an ability. They’re able to dodge out of the way, dispel its effect, or cancel the ability while it’s in progress.

A classic example of an ability with low counterplay is the older version of Teemo’s Noxious Trap. Noxious Trap lays down a mushroom which becomes invisible a few seconds after placement. The original trap lasted 10 minutes (nearly half the game for shorter matches), did up to 750 damage, and had 100% AP scaling, meaning that one AP equal one point of damage. Such a high-damaging item with a long lifetime was difficult to avoid, and a champion that stepped on one received damage immediately with no recourse.

An ability with counterplay is either avoidable or dispellable, to start with two basic ways of adding counterplay. Most offensive abilities in League of Legends are skillshots to ensure they’re avoidable by default. A skillshot is an ability that’s targeted by the player and doesn’t home in on the enemy. This way, the game maintains a closer correspondence between player execution (aiming/dodging skills) and success (hitting the enemy).

Buffs, debuffs, and traps have their own methods of counterplay too. Noxious Trap, like most stealthed objects, becomes visible under wards; combined with a lower lifetime and damage, Teemo’s ultimate ability is more avoidable than it used to be. The immediate damage isn’t as severe, and side effects from the trap like Slow are dispellable by abilities with the Cleanse characteristic, which remove all debuffs that suppress movement or ability usage.

Counterplay is important for a balanced ability, but fundamental changes to abilities tend to occur while the champion is in development or during a major rework. As live service support for the game continues, balancing also means making small adjustments to the efficacy of effects as issues crop up. As the game’s meta changes, so do the heroes and their viability. The following stats are values designers frequently adjust as new player data comes in.

- Damage

- Cooldown

- Cost (mana, energy, health)

- Range

- Cast time

- Type and effectiveness of other special effects

Where to find a MOBA game design template?

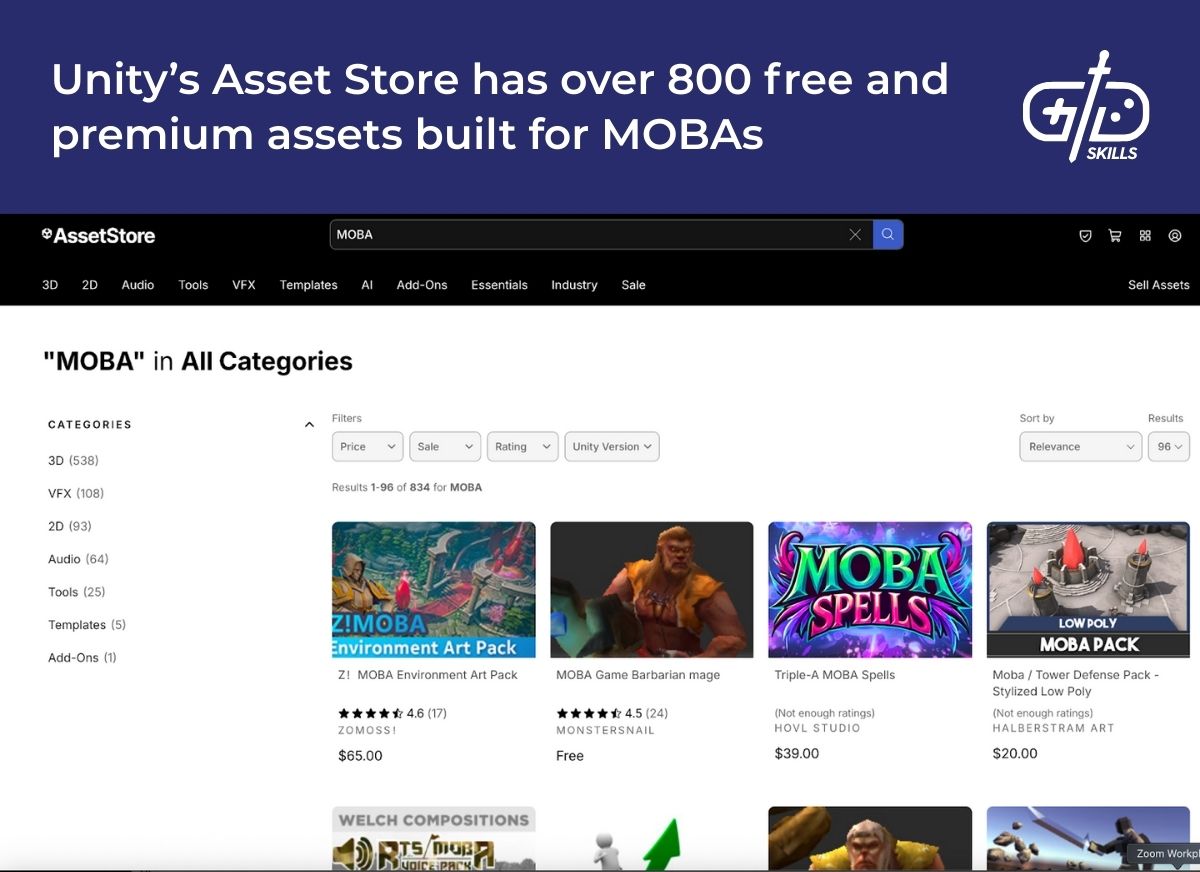

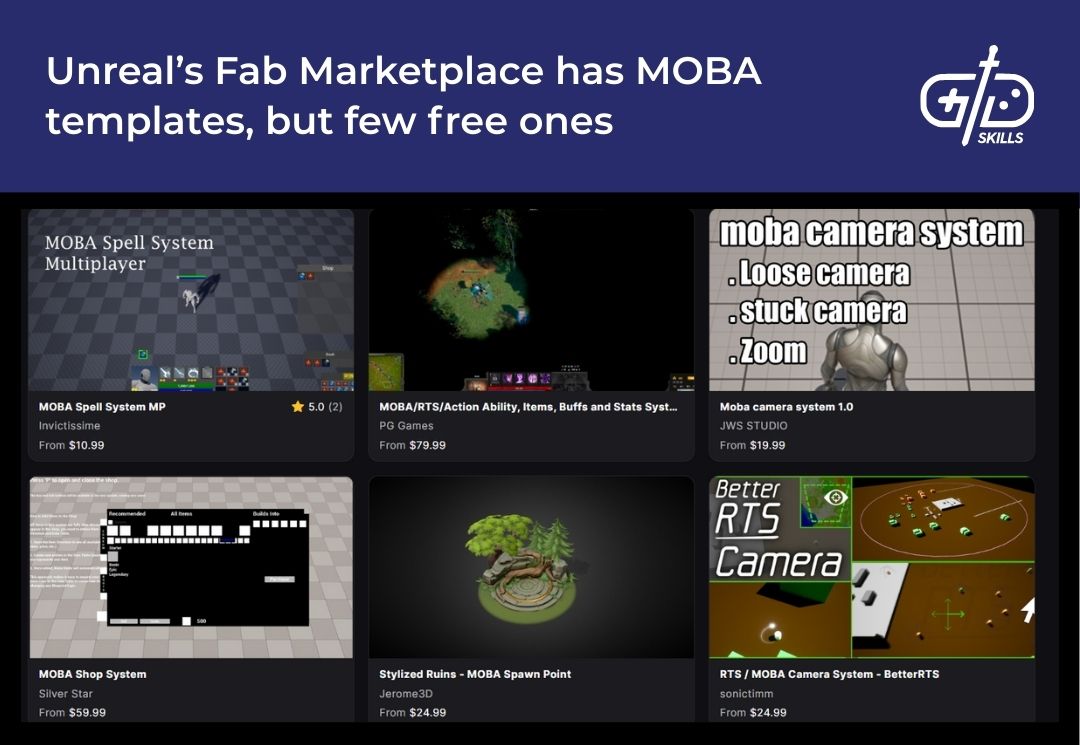

Find a MOBA game design template in Photon Quantum’s game samples, in asset stores, or just get started with modding an existing game. The Unity Asset Store and Epic Games’ Fab Marketplace are two of the most popular asset stores, although other options like itch.io are available with 2D and sound assets.

Photon Quantum includes a multiplayer-ready template for a MOBA on their website. Quantum is a plugin for Unity which implements multiplayer netcode and lets the user hook their game up to Photon’s hosting services. The service is essentially a whole new game engine under the hood, as it includes new Game Objects in place of Unity’s defaults (a Quantum Rigid Body instead of Unity’s default Rigid Body, for example). The MOBA included with Quantum shows the implementation of custom Quantum entities in motion. Player movement, inventory items, and the in-game lobby for character selection come built and ready. The template also comes with 6 example heroes, minions, neutral creeps, and the concept of visibility coded-in. Designers are able to start with multiplayer as early as the prototype phase with this template.

The Unity Asset Store has 800 MOBA-specific assets, the majority of which are 3D character models. The large number of art assets works well for a live service model where new cosmetics are a large portion of the business. The standard Unity EULA allows use of models for in-app purchases and marketing, so bringing assets in from the store for a MOBA isn’t legally problematic. However, a designer just getting started needs assets for pathfinding, character controllers, and game rules, which only the Photon Quantum solution provides. The Fab Marketplace does feature a MOBA Template from the seller Wild Sparrow which includes the map, movement, and creep AI, but this template is pricier at $299.99.

itch.io has similar terms and covers other assets that aren’t as common in the Unity asset store. itch.io doesn’t have as many 3D assets, but does contain voiceover files, male and female, for use in strategy games. The other advantage is the fact that itch.io has 83,000 assets available for $15 or less, including free offerings. The Graphicriver.net is another art marketplace with plenty of 2D assets available, including item, ability, and spell icons.

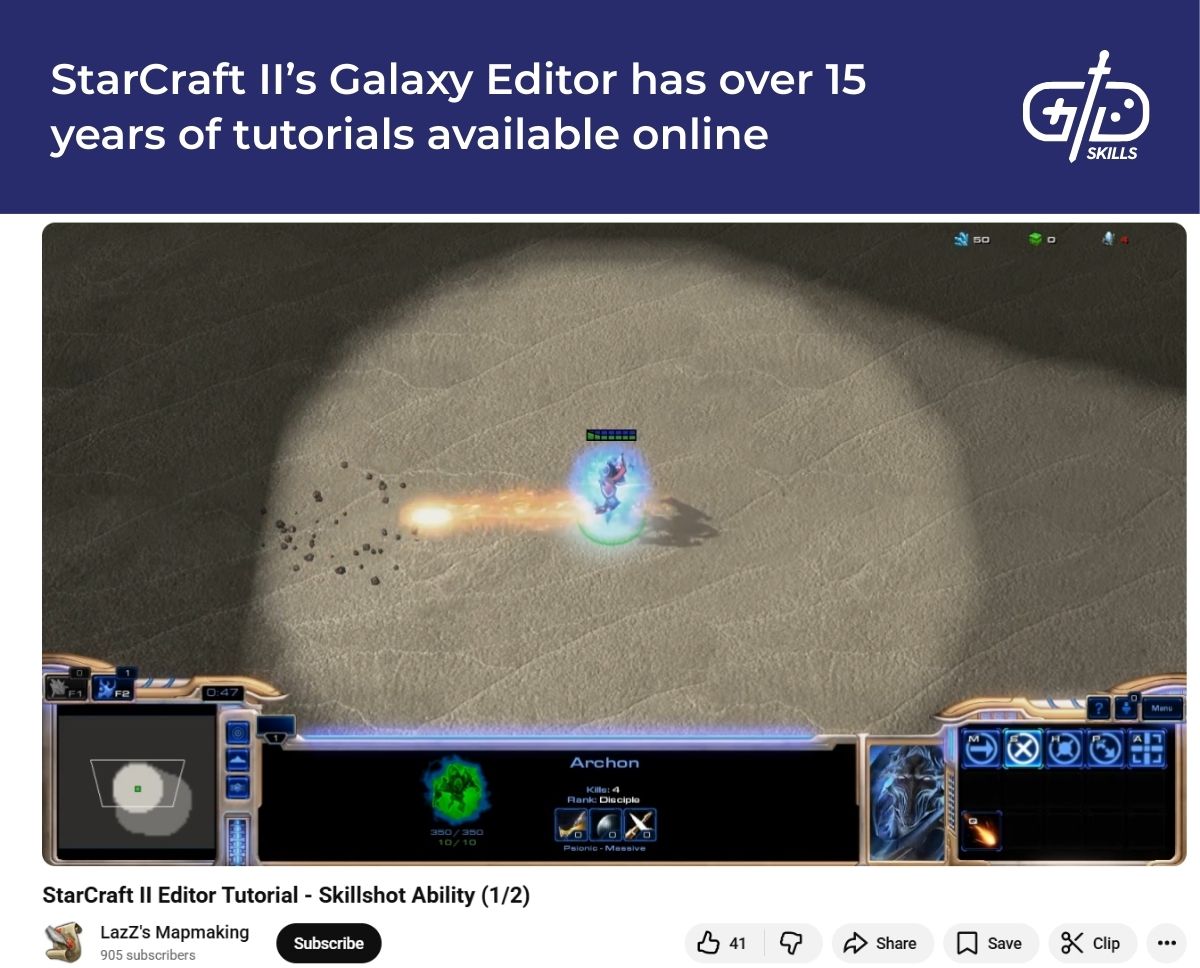

Modding is another way to build a MOBA without upfront investment. After all, the genre began as a mod, first as the 2002 map Aeon of Strife for StarCraft where players control only hero units, unlike the larger battles and economy management that’s normal for an RTS. The DotA series started as the mod Defense of the Ancients for WarCraft III, which led to imitators and the release of Dota 2 itself after Valve hired one of the modders maintaining it.

The older RTS games that spawned the genre are a suitable place to start with modding. WarCraft III’s editor is still functional and StarCraft II’s Galaxy Editor is a robust solution with extensive support through the sc2mapster Discord server. In fact, Heroes of the Storm is built on the same foundation as StarCraft II, so it’s possible to make mods for that MOBA using the same tools.

What is an example of a MOBA game design document?

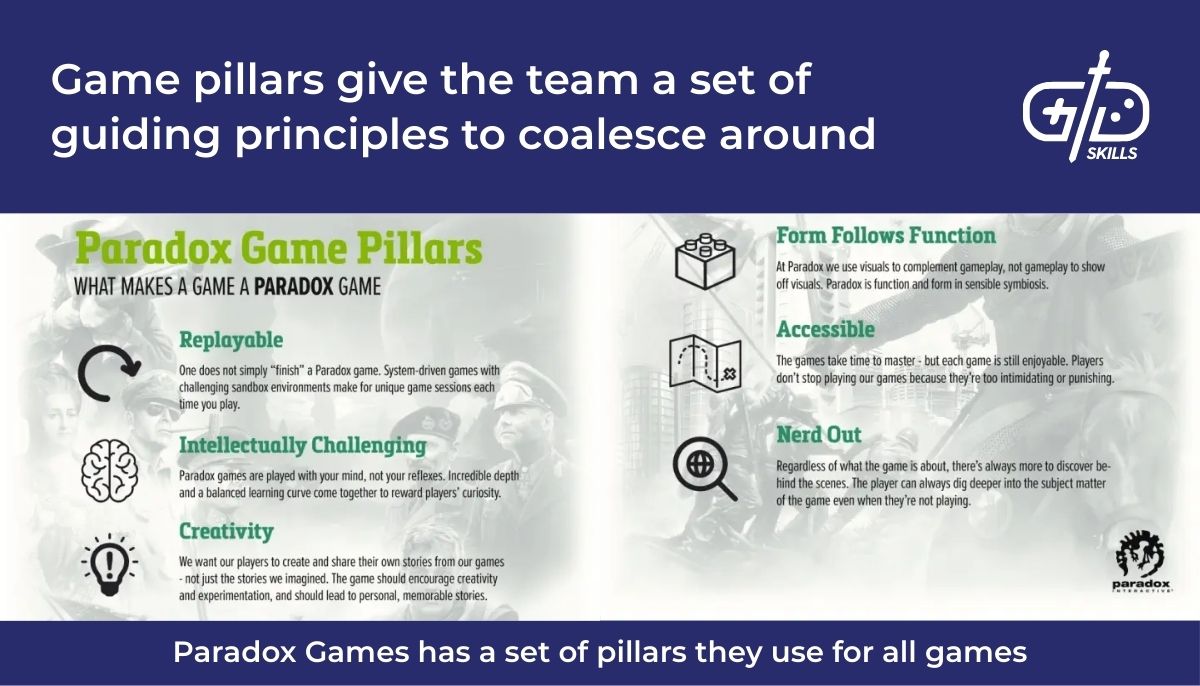

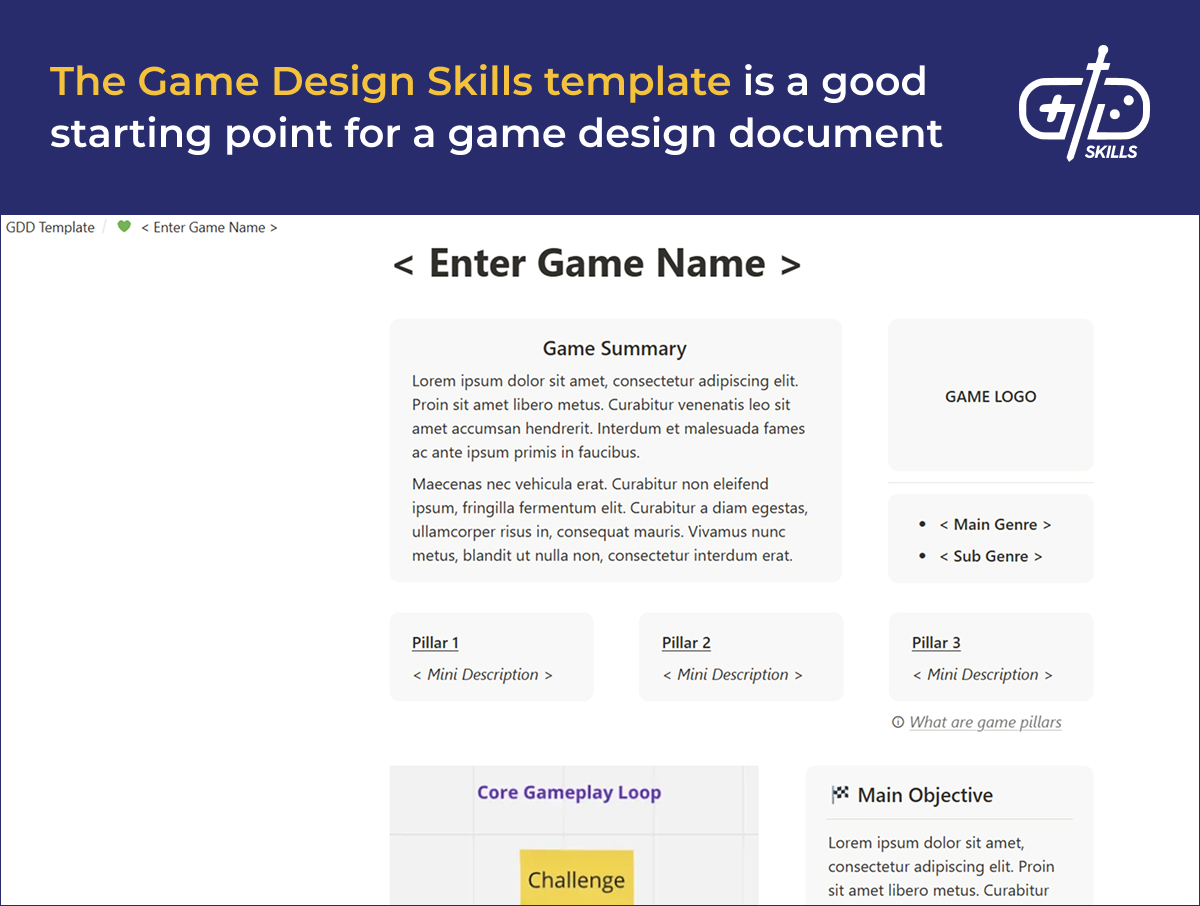

No examples of a MOBA game design document (GDD) are available. A GDD is a document that describes the game’s core pillars, mechanics, characters, abilities, art style, and narrative. MOBAs are live service games, so the guiding principles remain consistent over the course of their life, but the specific features and content are more dynamic than a single-player game. Starting with a GDD is a good way to organize ideas, but it isn’t the only way. Some developers opt for creating a wiki so that members of the team are able to update parts of it on the fly. If using a GDD, our template has all the necessary features for getting started.

A GDD starts with core information about the game, the one-page pitch for the team. It includes gameplay, environment design, and scope of the project. Game development is a multidisciplinary endeavor. Investors, publishers, producers, artists, and designers need to get aligned on what they’re building. When one of the developers begins to wonder whether their contribution makes sense for the game, the GDD is a touchstone which keeps them in step with the overall vision.

The main GDD comes in two flavors: a AAA document with more extensive space for presenting timelines and market research, and a solo dev document with shorter headers. Both GDDs list major features and describe the design, narrative, and art style.

The GDD remains as light on detail as it’s able to. Members of the team don’t want to wade through a heartfelt essay about the virtues of this or that game mechanic to get to the point. The GDS template includes simple feature documents for splitting up the information into manageable chunks. Headers break up the feature into the requirements for design, UI/UX, programmers, and footage of the feature in action. References to other games and a breakdown of the main goals for the feature give developers a clear, immediate view of what the final product ought to look like.