Text-based games depend primarily on words to create imaginary places, puzzles, characters, and choices with consequences. Text-based game design must play to the strengths of the medium by using clear language, engaging deliberately with the player’s imagination, and building a compelling world that feels reactive to player input and consistent in its internal logic. Designers of text-based games understand the unique elements of the medium and lean into them.

The first text-based adventure started life as a caving sim built by a caving enthusiast on an MIT mainframe. A fellow programmer and tabletop RPG enthusiast asked permission to add magical creatures, treasure, and other fantastical elements, and the text adventure genre was born. The expansive, free-roaming semi-open worlds of the Infocom catalogue from the golden era of text adventures are incomparable in their scope to the graphical games of the time. Read on to learn about the principles, mechanics, and storytelling techniques used in text-based games.

What are the principles of text-based game design?

The principles of text-based game design are clear, concise language, player agency, imagination as a design feature, a consistent game world, and compelling narrative design. Text-based game design depends on readable player feedback systems that feel intuitive, and challenges and rewards that make players feel that the experience is worth their time and effort.

Interactive fiction’s major deviation from traditional narrative media, such as books and movies, lies in the idea that the fictional world responds to player input and action. The role of the text-based game designer is to make the game feel real, expansive, and lived in. Let’s look at the underlying principles in more depth.

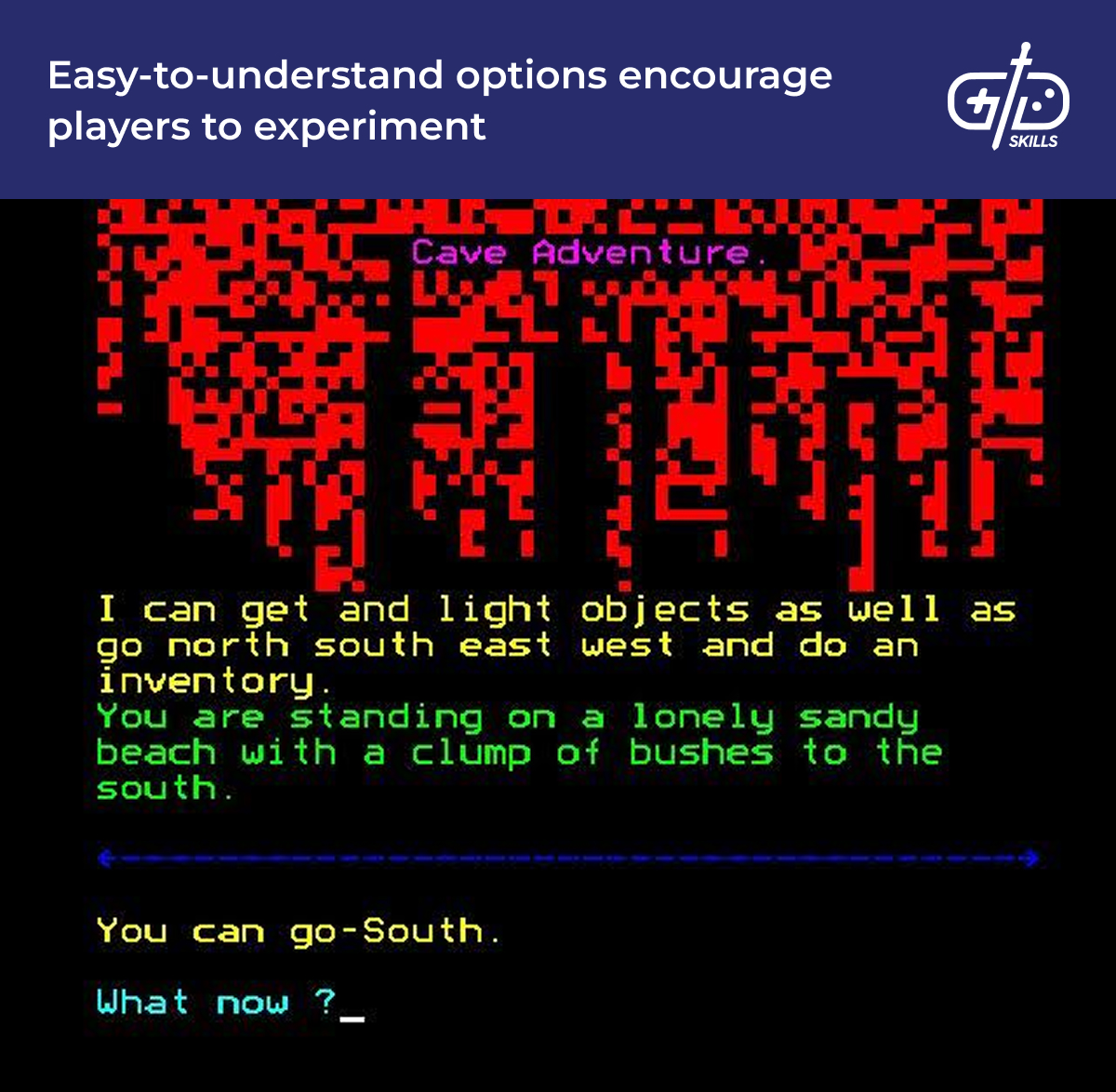

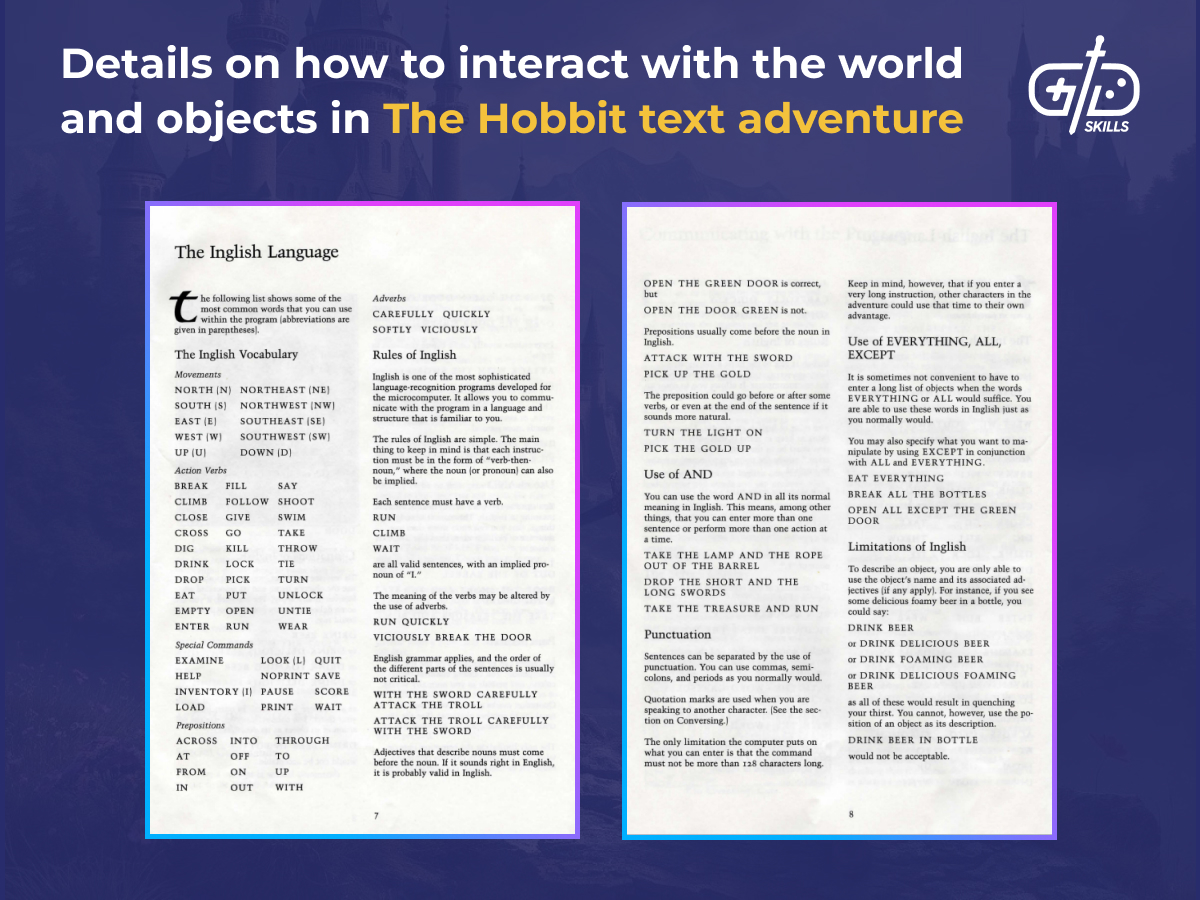

Clear, concise language is necessary in text-based games because the medium uses writing as a core mechanic. The player must understand what actions are possible and how to achieve them. A text-based game system must communicate this information through prompts, tutorials, or dialogue. The player must never be left blindly guessing which verb works in parser-based games, and the system must be capable of understanding player intent through synonyms, partial answers, or close guesses. Branching paths and options must be subtly signposted using font changes, colors, or other systems of highlighting options in text.

Player agency allows players to feel their choices have consequences and that the world is reactive. In a parser-based text adventure, the freedom is in experimenting and deducing which verb progresses the story. The player has freedom through imagining a potentially huge range of commands and interactions. Effective games narrow the purview subtly so that the player experiments within a predictable but fun range.

Choice-based text adventures deliver player agency through branching story or character options that alter the experience. Text-based RPGs add classes, levels, and gear, allowing for further agency through customization. Design interactions with characters and environments that encourage players to experiment rather than follow a series of rote steps. This allows them to feel connected to an emergent story.

Imagination as an intentional design feature is a part of text-based games because, like novels, they depend on the reader to generate a mental picture of events, scenery, and characters. The game world is built on words alone, so the prose must be evocative, setting the tone of the experience by consistently using a thematically appropriate style.

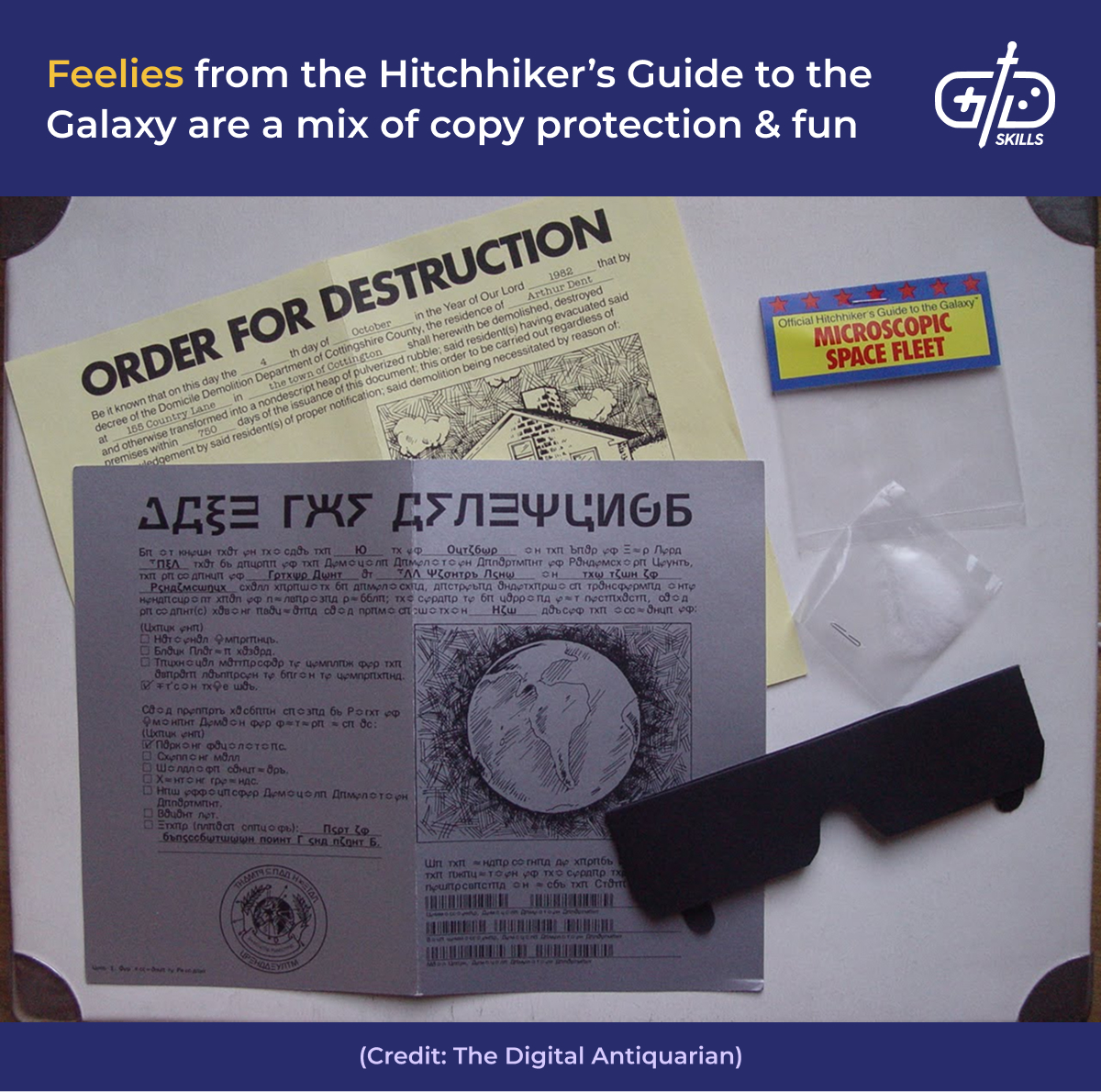

A graphical video game set in a crumbling castle depends on visuals and sound effects to transmit its atmosphere. A text-based game must describe the feel of the worn flagstone floors and the faint smell of dust and rot in the cold air. Early text-based games came with feelies – thematic objects from the game world, like maps, coins, and documents for copy protection and immersion.

Text-based games need consistency because players must feel like the game world and its inhabitants follow their own internal logic. Players get frustrated and disengage when something that worked before feels arbitrarily blocked in another context. Navigation, accessing inventory items, and dialogue selection must be predictable and homogenous across the experience. Maintaining continuity with objects, environments, and characters increases immersion. Objects that players move or alter (switches, doors, faucets, candles, etc.) must remain in the state the player left them in. NPCs and environments shine when they remember previous interactions with the player and respond to events.

Great narrative design is essential in a medium that’s (almost) entirely rendered in text. The prose and narrative must work hard in a text adventure because it’s replacing graphics, animation, and (often) audio. Designers of text adventures use several techniques to help make the narrative and language shine. Varying the rhythm of prose has a similar effect to a film director choosing fast edits versus slow, deliberate ones. Short bursts of text work for high-impact action. Longer passages work for worldbuilding, atmosphere, and the exploration of quieter areas of the game world. Evocative, descriptive text that avoids overly flowery language (unless intentional) and too-long walls of text helps keep players focused.

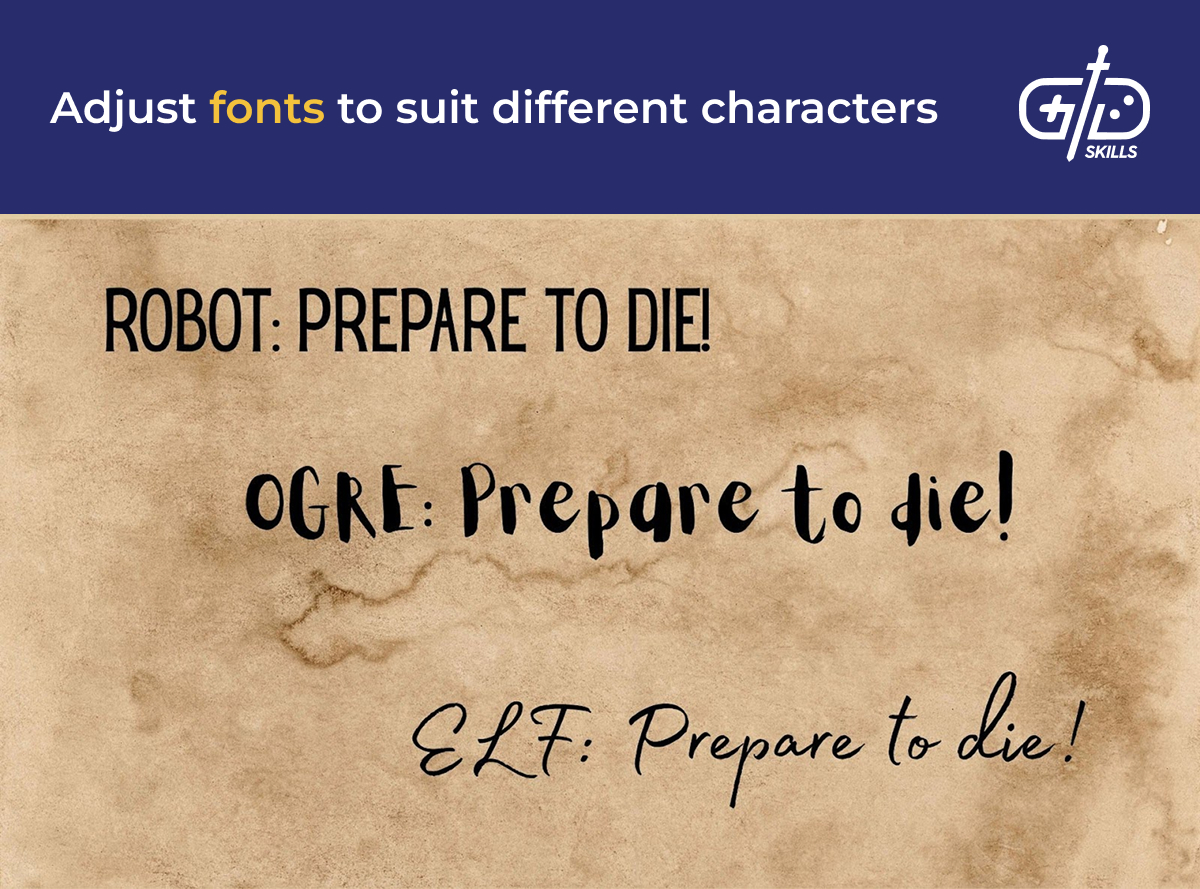

I think of the text like art assets when I create text-based games (because that’s what they are in a text-based context). Words are visual representations of the ideas in your head, and each word evokes emotional associations and reactions to its shape, sound, and even the font used. For example, when a monster enters the space for the first time, have your text represent that visually.

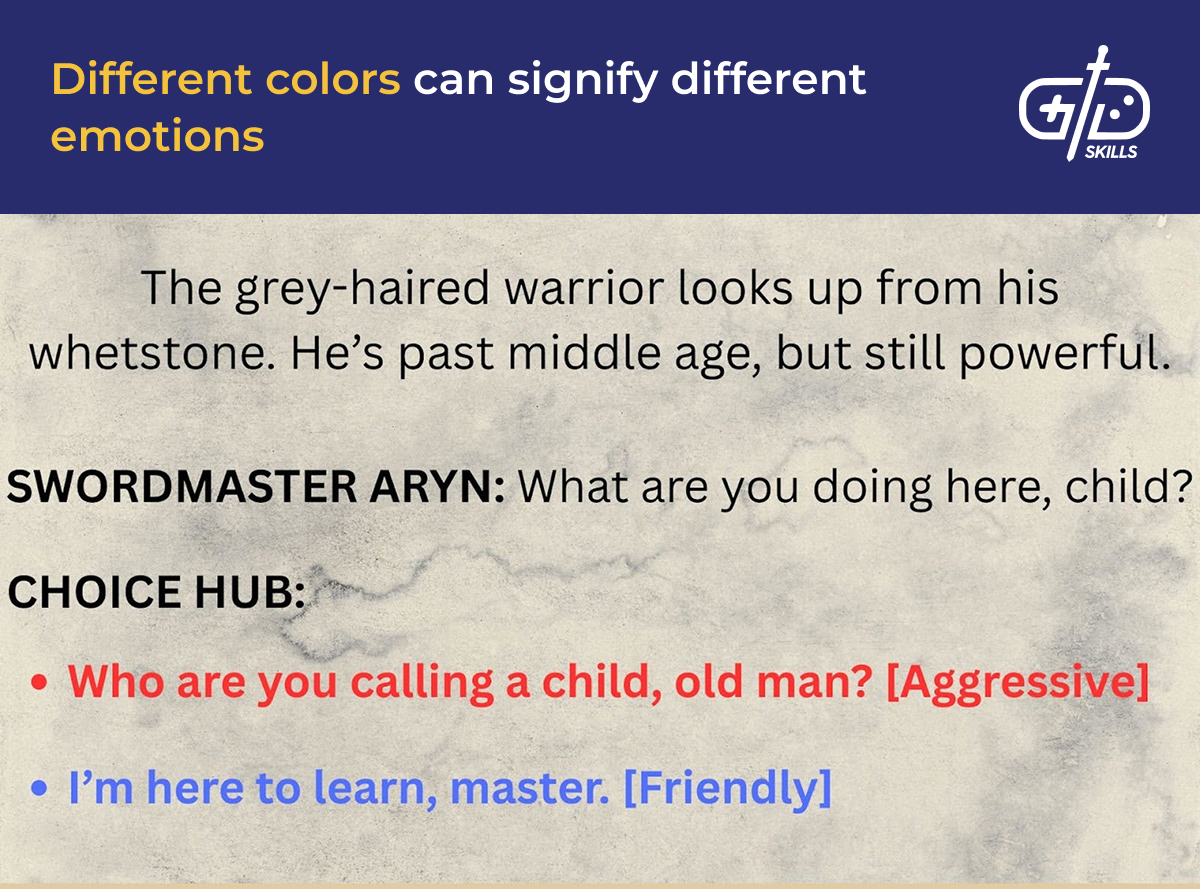

Like animated text, colored text cues expectations and emotions in the reader, reinforcing the feeling and tone. Colors help to transmit vocal effects and a range of emotional responses. Red text denotes an angry player choice, while purple represents a confused state. Avoid using green and red together in a set of options, as most players interpret those colors as representing “right” and “wrong” choices.

Use effects like animated or non-standard text to sparingly add flair without overwhelming the eyes. Text effects are to text adventures what salt is to the cooking process: a little improves almost anything, too much will spoil the experience.

When using color coding for emotional responses, always be sure to indicate the emotion in the choices. The key is to make it fun and simple to read without being overwhelming. Limit the number of colors used in any single situation, and double down on color coding and clearly printing the emotion behind each choice.

Player feedback is crucial to maintaining an immersive, low-friction game environment in a text-based game. Every action the player takes must elicit feedback from the game, even if it’s not the outcome the player wanted. When the player attempts to open a locked door, for example, give more detail than simply “the door is locked”. Instead, try “the door is locked, but you hear muffled voices stop suddenly on the other side.” The game must acknowledge it if the player attempts to use an item incorrectly, eg, “You can’t eat through the doorway, but the few bites you manage are unpalatable to say the least.”

Challenges and rewards act as the carrot and stick of text-based games, setting out a situation that needs resolution and offering a boon for doing so. Puzzles, if present, must feel logical, fair, and thematically linked to the narrative (don’t put an electrical wiring puzzle in a medieval fantasy, for example). Include clues, puzzle hints, and directions as natural parts of the text. The player must feel like they’re figuring things out, not randomly guessing the way forward. In text-based games, rewards include lore, new areas, and new equipment. Reserve the best rewards for the most deserving story beats to keep players excited to push forward.

How to design storytelling for text-based games?

Design storytelling for text-based games by establishing a distinct narrative voice, selecting a narrative structure for your story, and worldbuilding around these pillars. Developing characters with interesting relationship dynamics, conflicts, and tension allows designers to use character moments to vary the pace. Novels present readers with a series of events to experience as a remote observer, while text-based games give players a stage upon which to act. Offer players branching choices connected to NPCs with tangible consequences to create an immersive, interactive world.

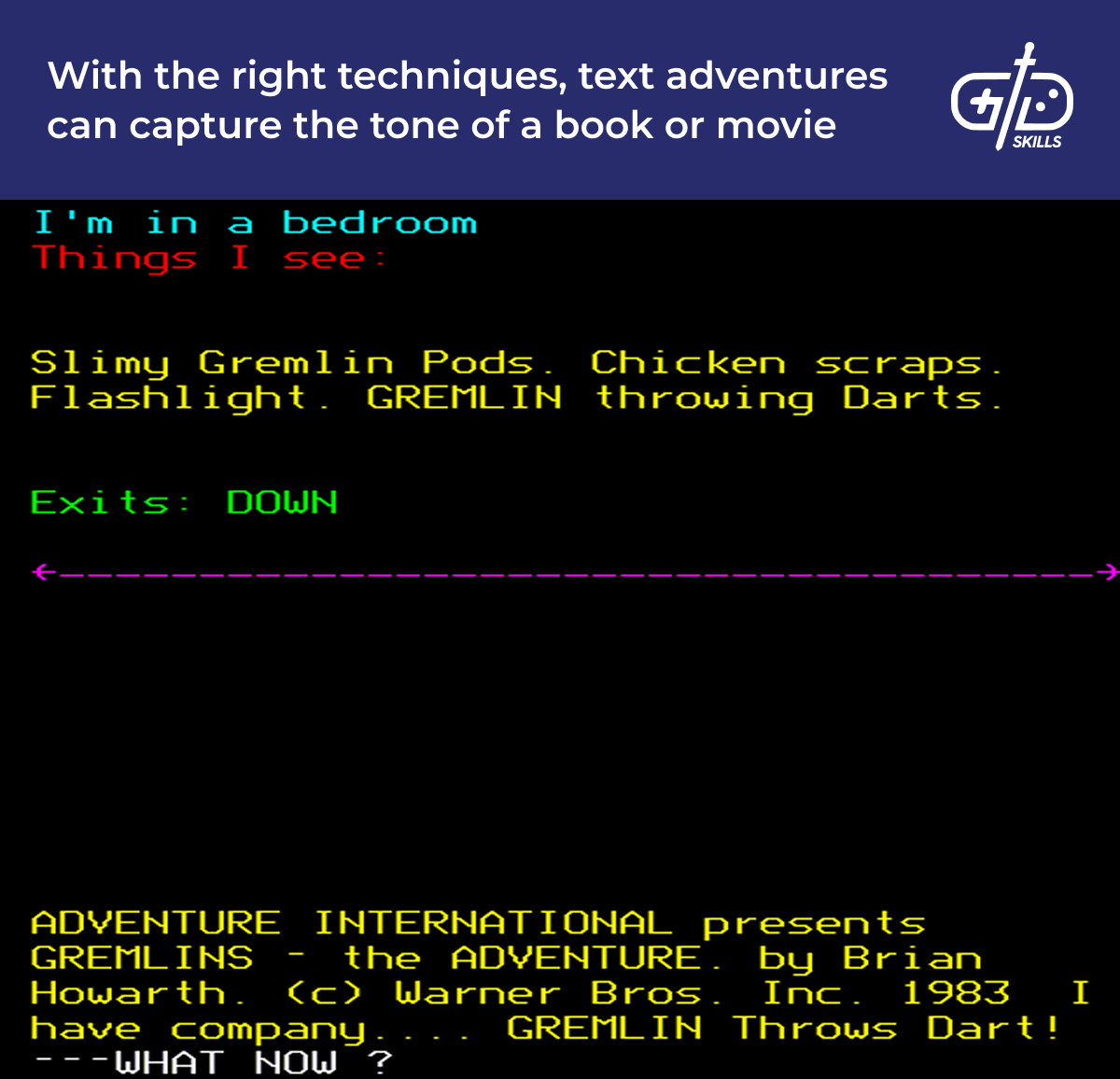

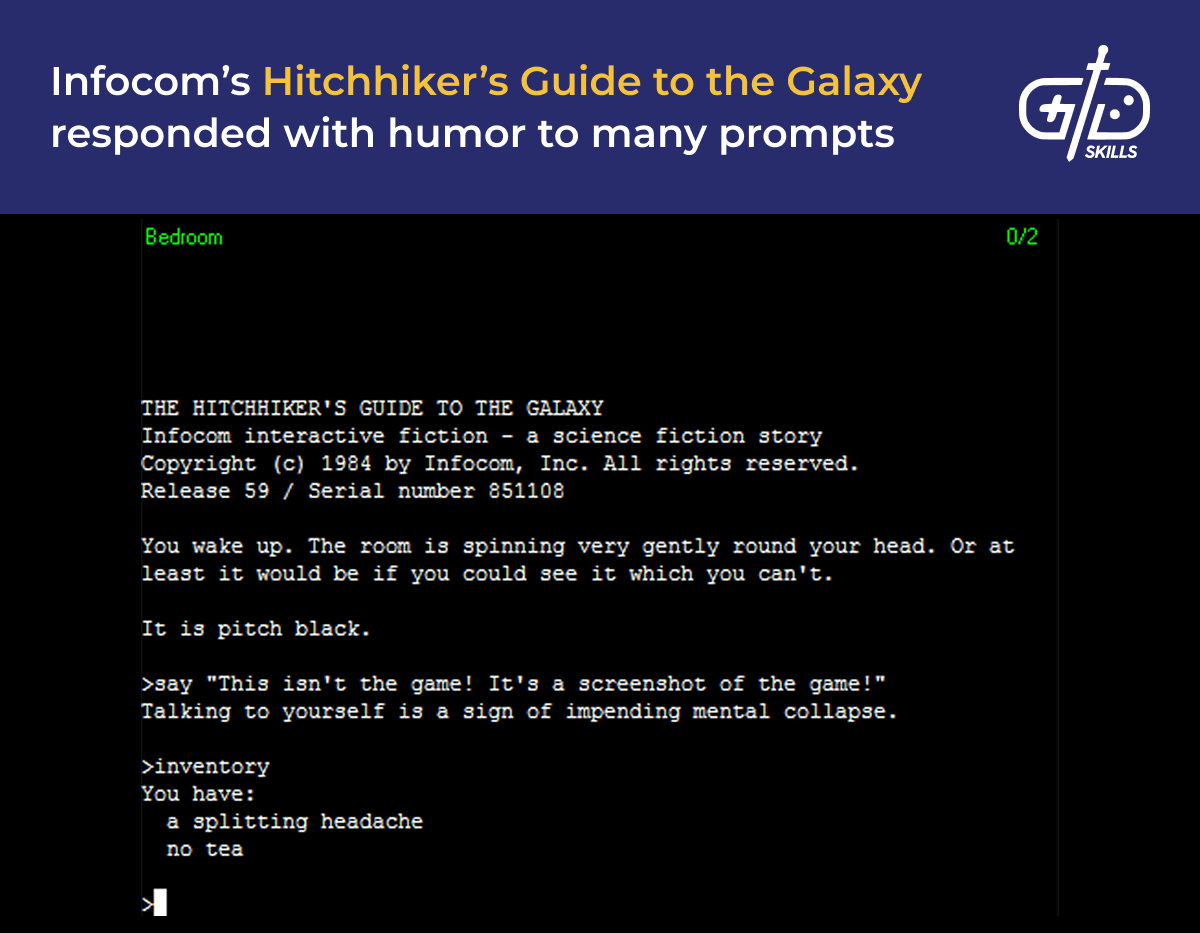

Effective text-based games, like all storytelling media, establish and maintain a consistent narrative voice. Designers must decide what tone their game will use and how to achieve and maintain it. Comedic, tragic, fantastical, mysterious, and surreal voices are common in the text-based adventure genre. Descriptions, options, and feedback must all stay thematically consistent. Even invalid commands must elicit responses that reflect the tone and theme of the setting.

The basic narrative structure of a text-based game boils down to two options: linear or branching. Linear narratives follow a single predefined path with shifts in tone and character alignment depending on player choices and actions. A linear story works best when designing a strong story with a single major resolution point. All paths lead to the same place, but the circumstances and attitudes of NPCs change based on player action.

Branching narratives are harder to write because they present many overlapping possibilities. This forces writers to consider how each choice impacts the others and avoid game-breaking conflicts. Branching paths offer higher levels of player agency and replayability, and suit narratives where characters, tone, and player power fantasy are as central as story.

Worldbuilding in text-based games can’t come from stunning backgrounds, costumes, and animations. Designers of text-based games must build wonder and immersion by using selective, evocative text that encourages imagination without swamping the reader with walls of text. Humans don’t walk through the world making a pointless itinerary of every object we sense. Instead, we allow our senses to guide us to the most important information in any given circumstances. Treat players the same way, guiding them through the game world using their senses as the anchor point. Allow the player to experience a curated view of the most interesting parts of your fictional world and its inhabitants through their five senses.

Interesting, distinctive characters with relationship dynamics that the player is able to influence make a game feel real. Write characters according to what the storytelling needs and already has. Creating characters that are opposites makes room for them to clash on important issues. Having a range of character archetypes with different motivations means the players find an ally regardless of which way they choose to play. Relationship dynamics and emotional arcs are only possible when there’s conflict, loss, or the threat of conflict and loss. Don’t be afraid to put your good characters in awful situations. The most fulfilling payoffs come from snatching victory from the jaws of death.

What are examples of text-based games?

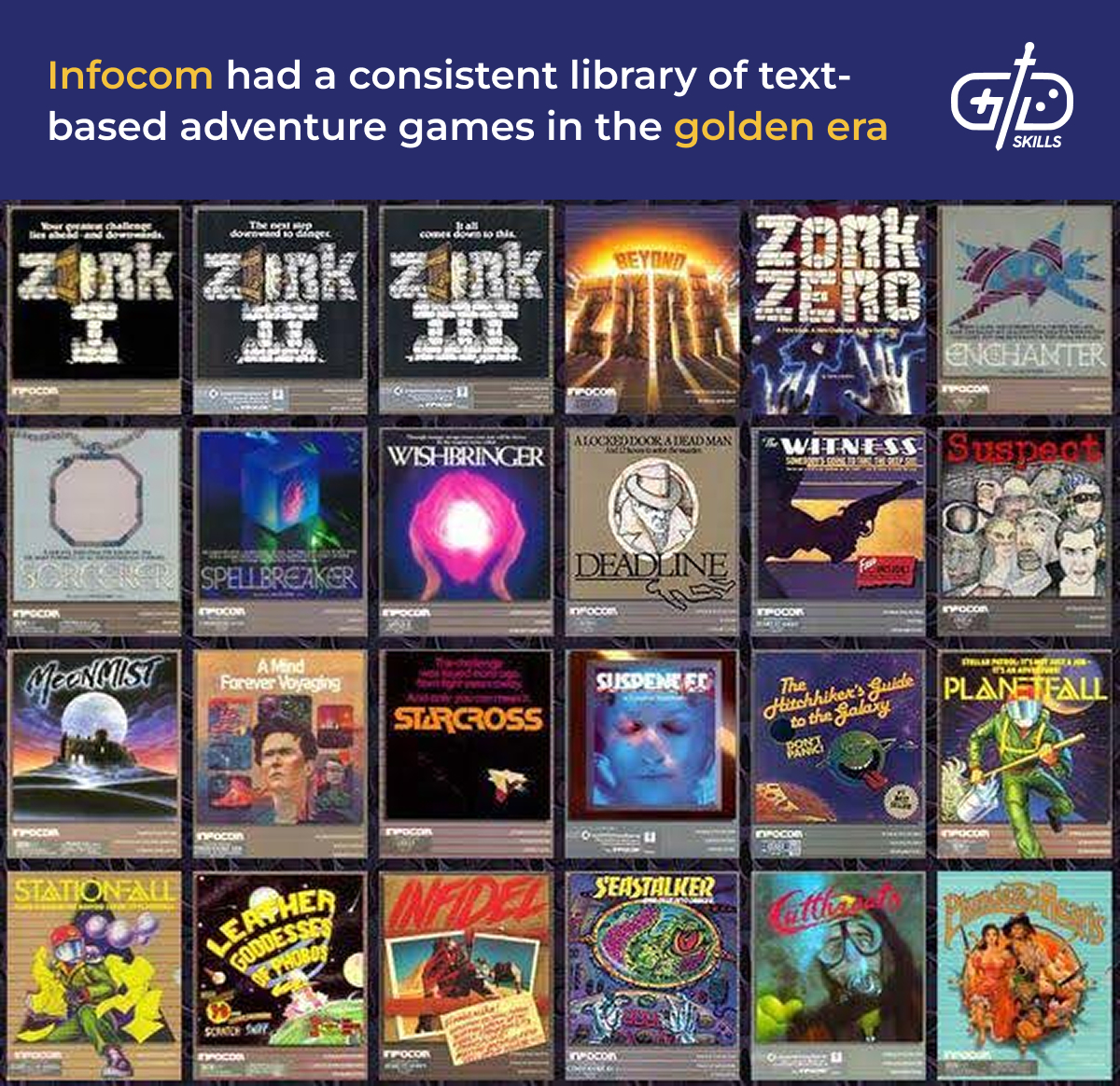

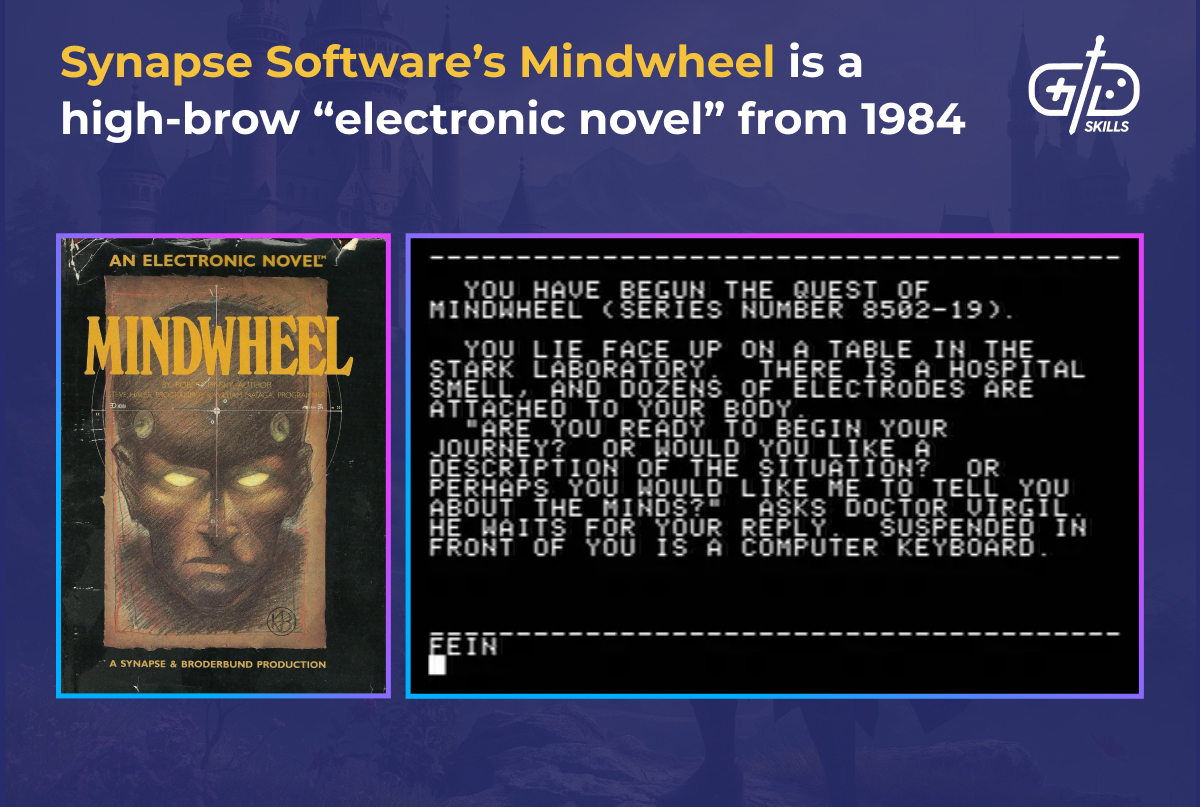

Examples of text-based games are Colossal Cave Adventure, Infocom’s classics Zork and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (co-designed by Douglas Adams and Steve Meretzky), and Synapse Software’s critically acclaimed Mindwheel by poet and writer Robert Pinsky. The golden age of text-based games is generally considered to be the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, when graphically impressive PC games began to take over. A text-based renaissance began in the late 2000s and 2010s with modern indie titles like Fallen London, Sunless Sea, Roadwarden, A Dark Room, and Buddy Simulator 1984. The new wave of text-based games often subverted player expectations from earlier games and other media through clever writing.

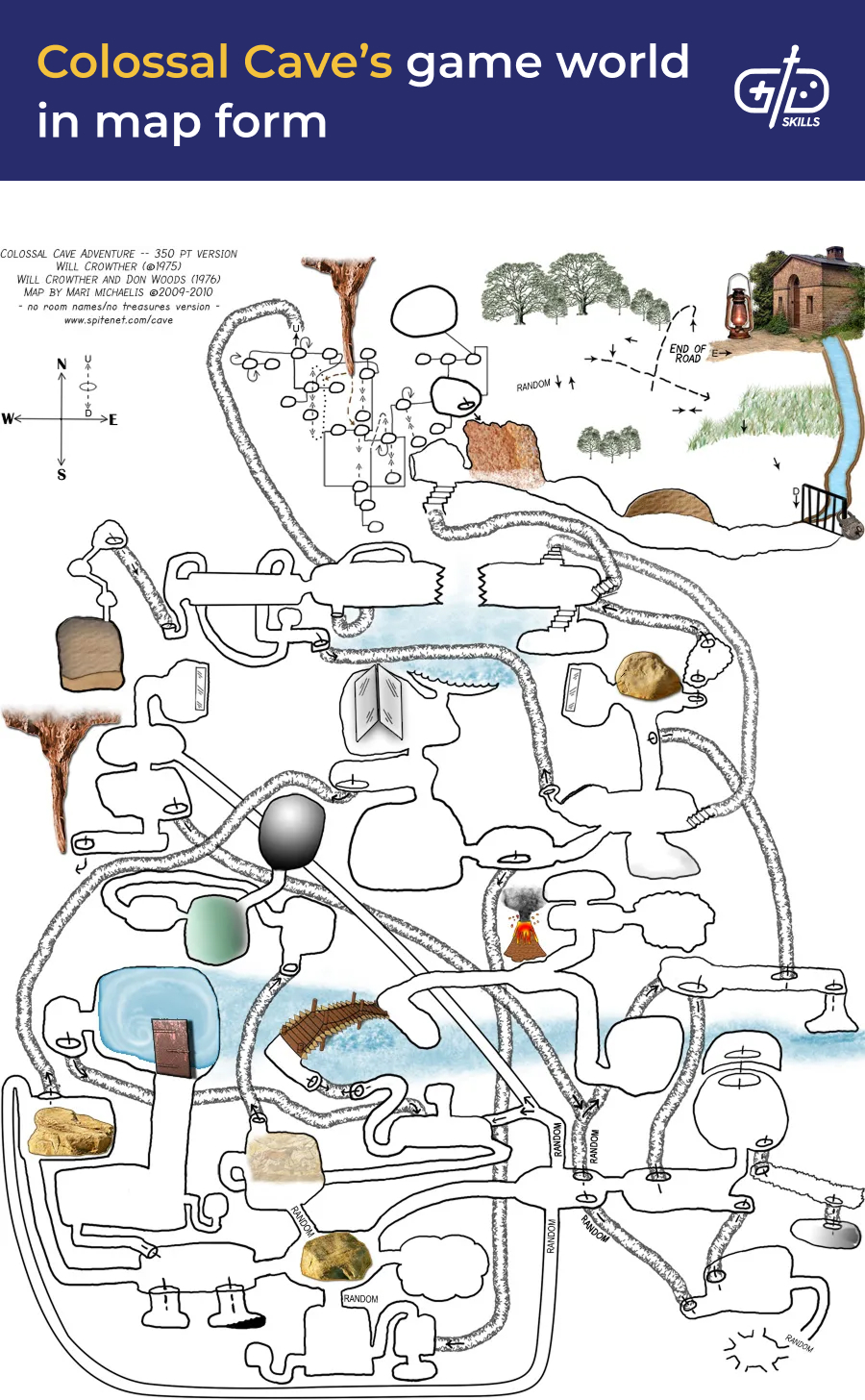

Colossal Cave Adventure was created by programmer Will Crowther on a PDP-10 mainframe at Stanford in the mid-1970s. Crowther was a caving enthusiast and used his knowledge to describe and lay out a realistic cave system, loosely based on Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave system. Don Woods discovered the game on the mainframe and expanded a largely serious cave sim computer program with fantastical RPG-like elements like dwarves, magic, and treasure. This version of the program spread through the ARPANET system and would go on to become one of the most influential computer games of any genre ever.

Zork was released by Infocom in 1980 for personal computers, but designers Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling began working on the project at MIT in the late 1970s. Inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure, Zork allowed players to explore a larger, more fantastical Great Underground Empire than Will Crowther and Don Woods’ classic cave exploration sim.

Zork’s sophisticated parser system allowed for more natural command inputs than Colossal Cave Adventure’s limited two-word commands. In Zork, players strung together logical sentences like kill troll with sword. Players collected treasure, solved puzzles, and avoided monsters. Infocom split the game into three commercial releases: Zork I, II, and III to maximize revenue.

Steve Meretzky was Infocom’s top designer in 1984, having worked on their highly successful Planetfall title. Infocom paired Meretzky with the author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams, to produce a text-based adventure of Adams’ best-selling novel. The player acts from the perspective of Arthur Dent on the day the Vogon fleet destroys the Earth. The inclusion of Adams as writer and designer means the game retains all the dry, self-aware humor of the novel. Infocom’s parser system understood long, complex instructions from the player, such as: “Take the satchel, open it, put the junk mail inside, and then close it.” The inclusion of and then to create multi-step processes was remarkable for the time.

Synapse Software released many successful arcade-style games for the Atari 8-bit systems, but also expanded into a range of high-brow, literary computer entertainment. Mindwheel, from 1984, was written by poet Robert Pinsky (who later became Poet Laureate of the United States). The game system operated like Infocom classics, but the themes and goals were loftier. The player takes on the role of a cybernaut entering a digital realm of consciousness, journeying through symbolic landscapes and interacting with archetypal personalities, the Poet, the Musician, the Scientist, and the Tyrant. The goal is to lead humanity to its next level of consciousness.

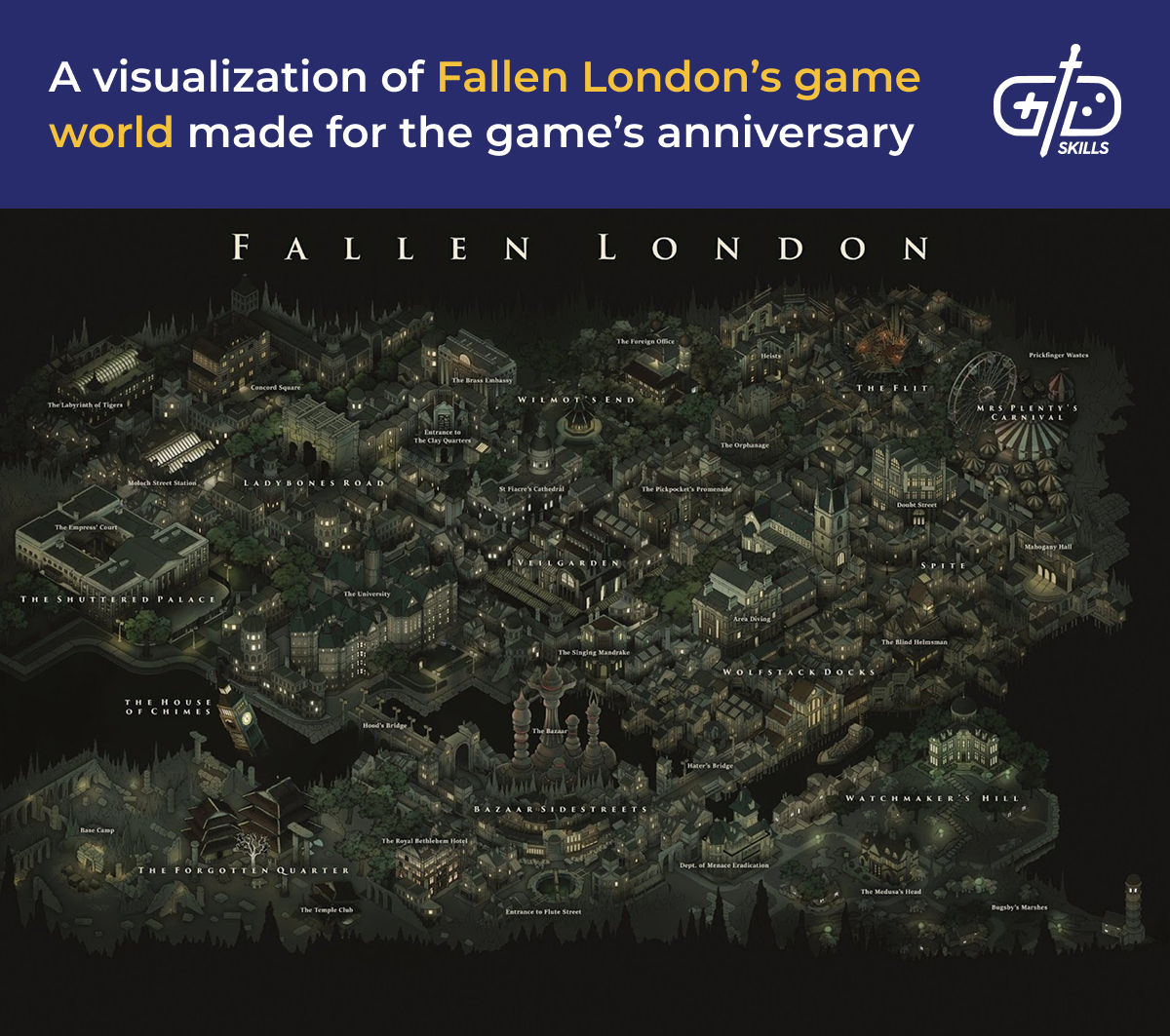

Fallen London, from 2009, blends old-school text-adventure with a persistent world that depicts a detailed alternative subterranean Victorian London. Initially browser-based, Fallen London was later released for mobile devices. Players enter the game world and make choices that affect the traits: Watchful, Shadowy, Dangerous, and Persuasive. These traits unlock different abilities, options, and storylines. Fallen London features factions, branching options, social interaction, and a critically acclaimed, vivid game world rendered entirely in text. The development team on Fallen London went on to work on Sunless Sea, a survival roguelike with strong narrative elements delivered through text.

Unlike Fallen London’s rich, evocative language, Amir Rajan’s A Dark Room uses minimal prose to create tension and urgency. Its story begins simply and grows organically as the player interacts with the game world and reveals more options. The designer leans into the limitations of the medium, building tension around the questions of where you are, who’s outside the room, and what’s happened to the rest of humanity. A Dark Room begins like a straightforward text adventure, but blossoms into a full-fledged exploration/survival simulation rendered in text form.

What mechanics are used in text-based game design?

Mechanics used in text-based games include parser-based input, choice-based interaction, character and dialogue systems, stats and traits, exploration and mapping, item and inventory management, puzzles, and time mechanics. Without graphics, text-based games must create immersion, depth, and agency while depending on the player to build a mental picture of events. Text games achieve this using elements of adventure games, RPGs, and survival games.

Players type in natural language to interact with items and characters in the game world in a parser-based game. Classic titles like Zork and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy use parser systems that allow players to feel connected to the fiction in a way that selecting options doesn’t replicate. Using natural language to attempt to manipulate or interact with the game world, such as “Put the towel on the satchel and lie down” (Hitchhiker’s Guide), is complex, but it makes players feel like they’re acting and carefully considering their options. The drawback of parser-based systems is that they feel arbitrary when poorly executed. Frustration never feels far away to the uninitiated playing classic parser games.

Choice-based interaction lacks some of the freedom of parser-based systems, but has a much lower risk of player frustration. Pre-defined options replace freeform typing and thinking to deduce the correct verb combination. Games like Fallen London and A Dark Room offer clickable choices that streamline interaction (arguably reducing immersion for some) and allow for many branching options. Each narrative chunk of Fallen London contains choices. Selecting certain choices results in unlocking new story content, changes to your stats, failures, and successes. Like an RPG, player stats influence the likelihood of passing checks based on personality traits. The stack of choices and consequences that make up your current state makes each character feel unique.

Dialogue is the core way players interact with text-based games. Descriptions and typed commands are a form of dialogue with the narrator. These interactions, and those with the NPCs, must give the player a sense of agency and allow them to roleplay, influence events, and decide who to side with. Characters in older, Infocom-era text games lack the depth of modern NPCs in Fallen London, where player success or failure in dialogue hinges on stat checks like an RPG. Players feel more connected to their choices when their failure or success is directly linked to their character build and previous choices. NPC’s memories allow players’ earlier choices to ripple forward, remembering a negative encounter or a time the player helped when they didn’t have to.

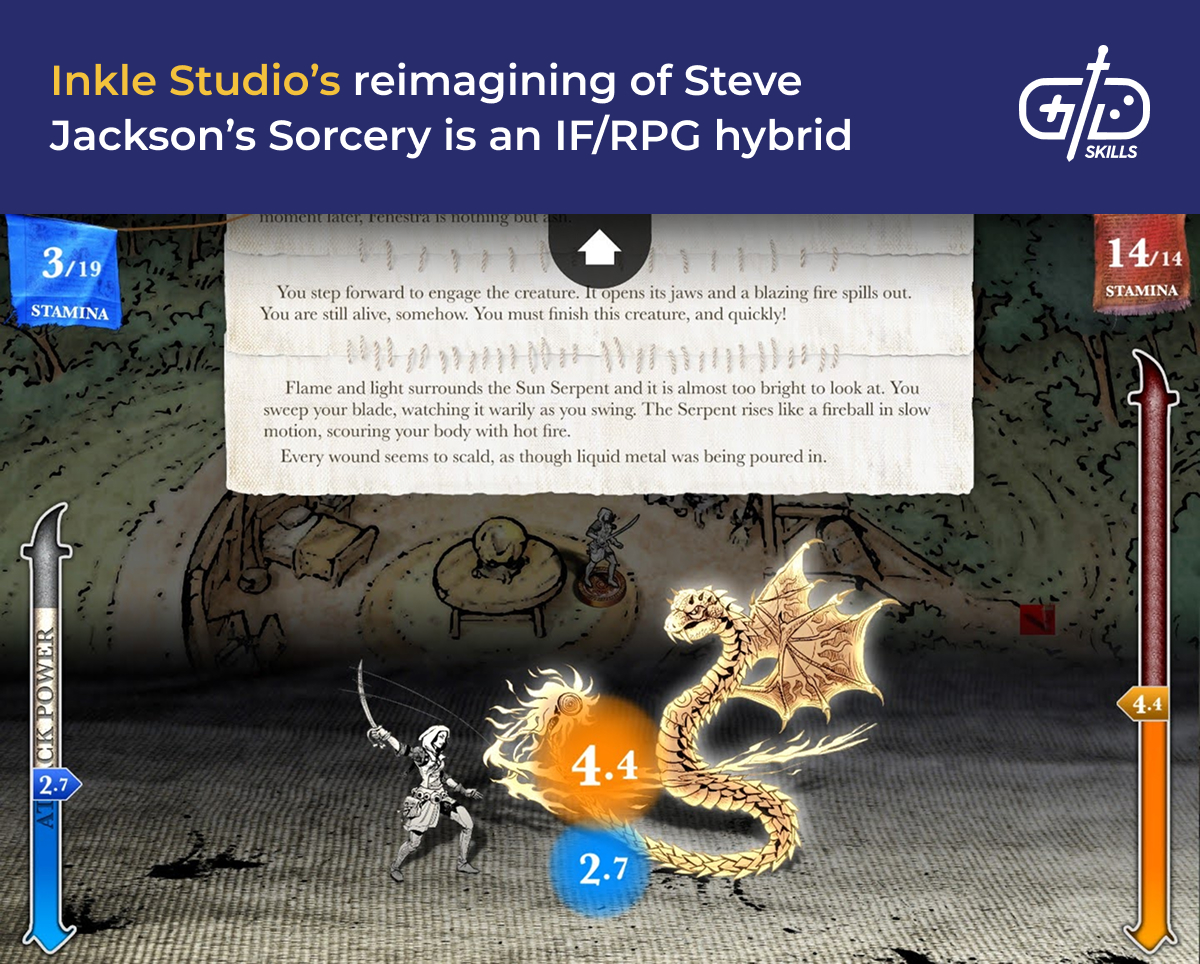

Stats and traits are mechanics borrowed from the RPG genre and used in text-based games like Fallen London, Sunless Sea, and 80 Days. Fallen London uses a four-trait system based around Watchful, Persuasive, Shadowy, and Dangerous traits. Player choices result in changes to these stats, and success or failure in dialogue and skill checks hinge upon the relevant stat, like an RPG. Inkle Studio’s reimagining of Steve Jackson’s classic Sorcery books uses stamina, spells, and inventory management to resolve conflicts, dialogues, and other situations. 80 Days bases success and failure on stats like money, health, and reputation. Stats and traits in text-based games add to the interactivity, but work best when they avoid the long, complex systems of CRPGs and simulations.

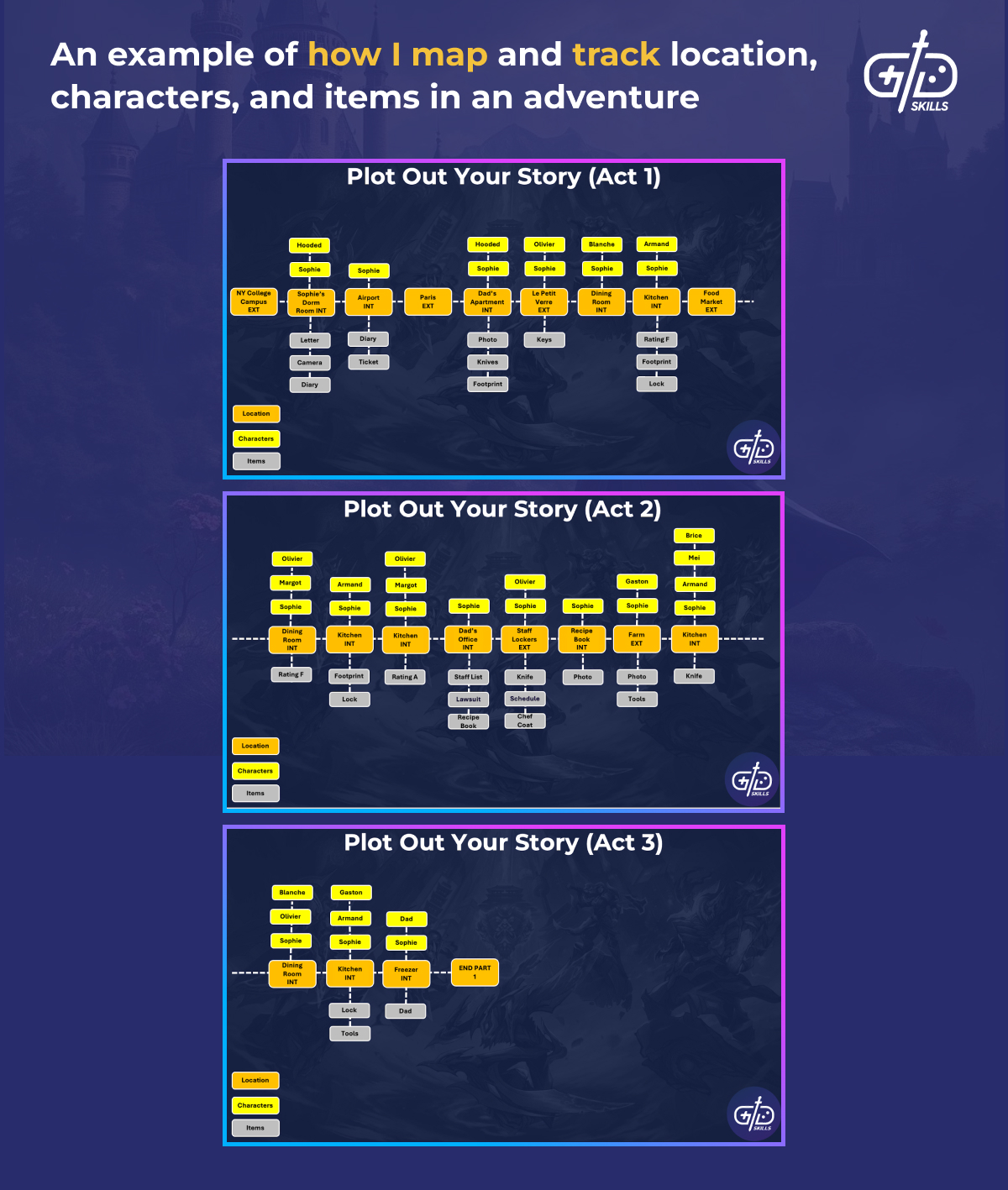

Exploration and mapping were key features of early interactive fiction games like Colossal Cave, Zork, and The Hobbit. Like in the dungeon-crawling style of tabletop RPGs of the time, players were expected to use a pen and paper (“pen and paper RPG” was a synonym for the term “tabletop RPG” for several decades) to map out rooms, corridors, doorways, and other notable features. Without this paper map, the Underground Empire of Zork would be impossible to navigate intentionally. Modern text-based games like Fallen London, 80 Days, and A Dark Room maintain exploration as a core component of gameplay, but no longer expect players to create a paper map of the areas they explore.

Items, inventory, and resource management have been a part of the text-based adventure genre since its inception in the mid to late 1970s. Colossal Cave Adventure featured a basic item set like lamps, keys, treasure, and tools. Carrying too much weight impeded progress, forcing players to consider inventory management. Puzzles required specific items to solve (eg, a lamp to progress through a dark area). Zork expanded inventory items beyond simple lock and key mechanisms with weapons and consumables. Limited inventory space forced players to consider their options carefully. Infocom’s classic titles like Planetfall, Enchanter, and Deadline introduced specialized, thematic objects like spellbooks and medkits, but also featured red herrings like spare parts with no real function.

In classic parser games like Zork or the Infocom catalogue, content is gated behind simple puzzles of lock and key pairs. A lamp is required to progress through the dark area, for example. In these games, the game world is static, and combining items, solving riddles, or finding the right object are the primary means of interaction. “Use X on Y” is a classic method of puzzle-solving in parser-based games. Text-based games use implication to guide players towards the solution. For example, “the rope is slightly frayed” or “the lock is rusted on one side” suggest that, with the right interaction, the player is capable of altering the state of these objects. Logic and wordplay puzzles must be effectively integrated into the narrative and fit the tone. Wordplay is often goofy and whimsical, meaning it doesn’t work in darker, more serious fiction. Logic puzzles need to have their solutions signposted without being blatantly obvious.

In classic, Infocom-era interactive fiction, each movement, such as “go south” or “take key,” advances time by one turn. A simple, one-action = one-turn system allows designers to build narrative tension and build a plausible, lived-in world. Time passing allows resources like lamp oil, food, and water to become strategic elements of gameplay through limitation. Food spoils (or gets eaten), oil burns, and water gets drunk, making time a central mechanic and putting pressure on the player. NPC and environmental changes work alongside the player-driven time mechanics to reinforce a living feeling world. For example, a vendor is unavailable at certain times, or heavy rain or other time-based weather effects change the location of a certain NPC.

Where to find a text-based game design template?

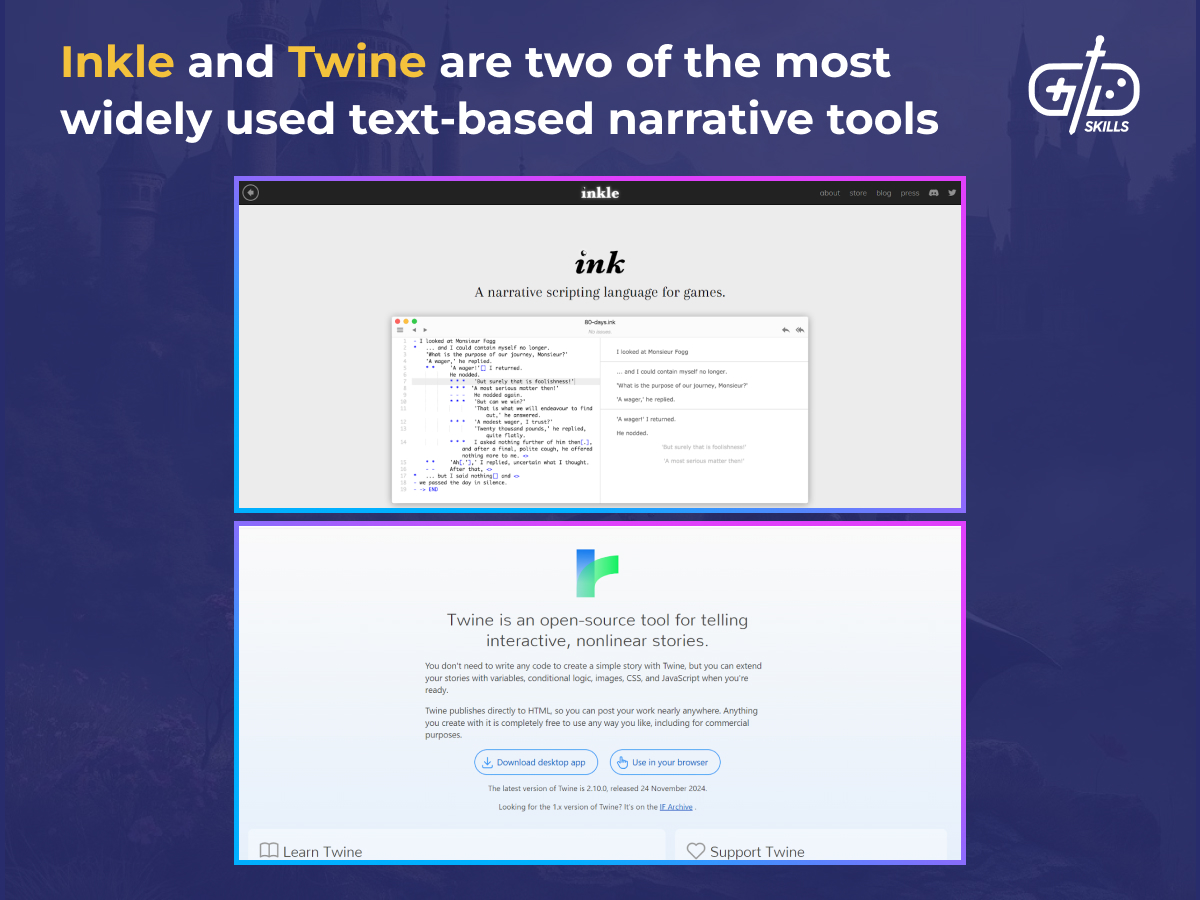

Find text-based game design templates at online platforms like GitHub, itch.io, Miro, Notion, GameDev.Net, Reddit, and at GameDesignSkills.com. Specialized communities centered around text game development tools like Twine and Ink by Inkle help designers learn the ropes quickly and get the most out of their platforms. Most game design documents are adaptable to a text-based format by simply omitting the irrelevant sections like art design, sound design, and technical sections that don’t apply.

Online platforms offer templates that help you plan the stories, choices, characters, and challenges of a text-based game. GitHub features several Python and JavaScript templates to help designers get started. Text-adventure-game on GitHub is a simple Python template with a toggled commented and uncommented mode. Turn comments on for tips, ideas on expanding their narratives, and explanations of key mechanics. Okaybenji/text-engine is a lightweight text adventure template that’s easy to use and perfect for making embedded dialogue on web pages.

Itch.io features an Interactive Fiction Template (by Jeneara) designed for text-based narrative experiences. For designers working in the Ink format, the Interactive Story-Telling template by All Worms is recommended, while Twine designers must check out the Sugarcube or Harlowe templates that offer minimalistic or highly stylized interface options. Itch.io also contains many templates for visual novel-style experiences, such as the Disco Elysium-inspired Disco Framework, or several options for Ren’Py creators.

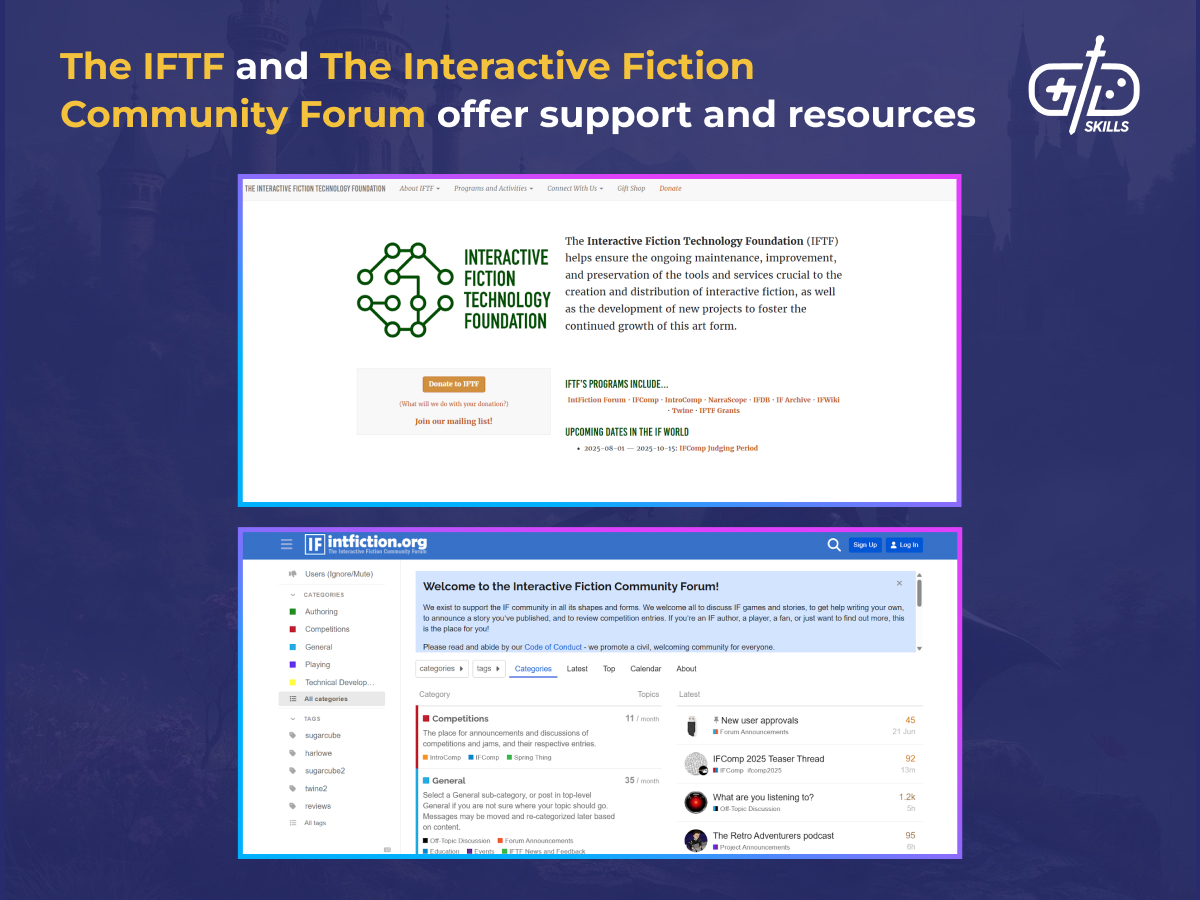

The Interactive Fiction Community Forum is the largest hub for parser and choice-based games, running competitions, community playtesting, feedback, and news. It’s a supportive community that hosts many community-driven projects and helps designers create memorable experiences. The Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation is a non-profit that runs the Interactive Fiction Database and works to preserve the tools and services crucial to the distribution of interactive fiction.

What is an example of a text-based game design document?

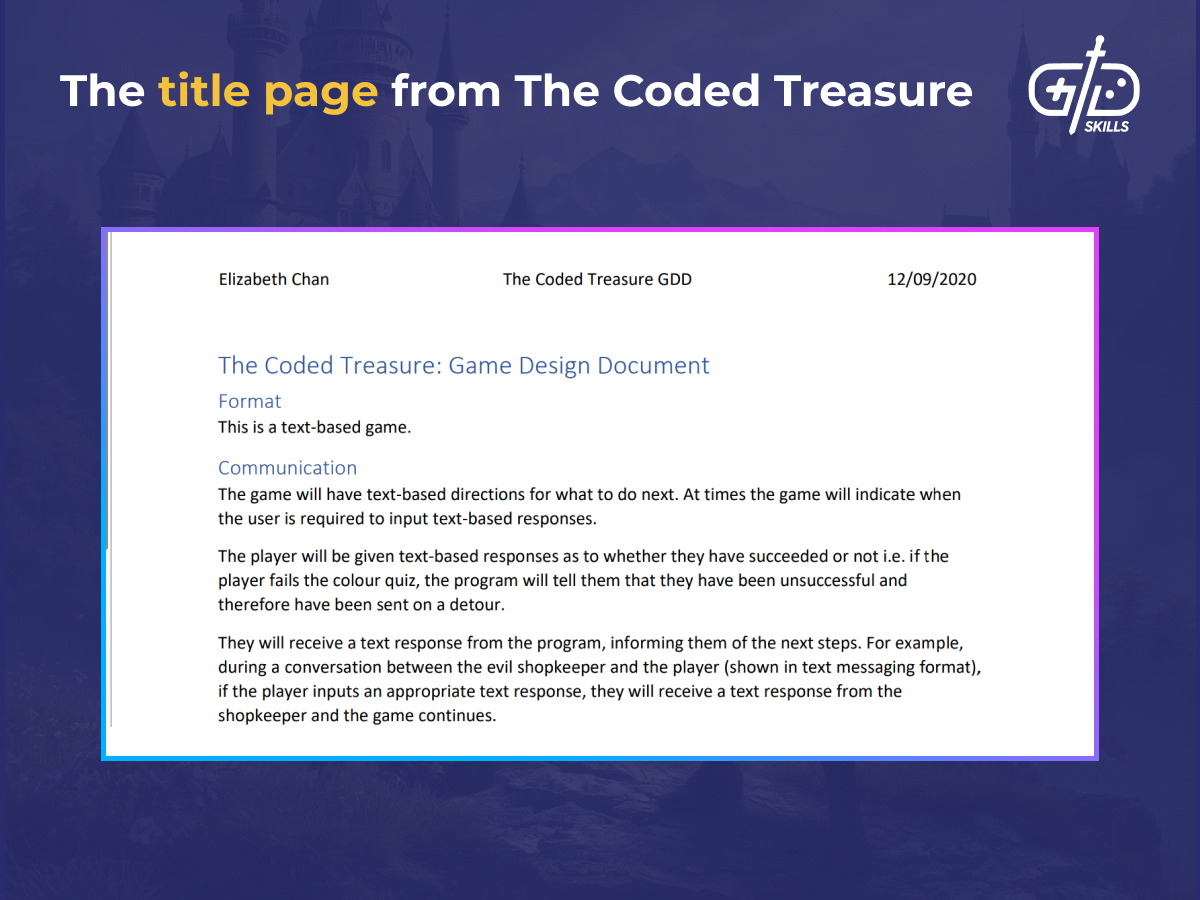

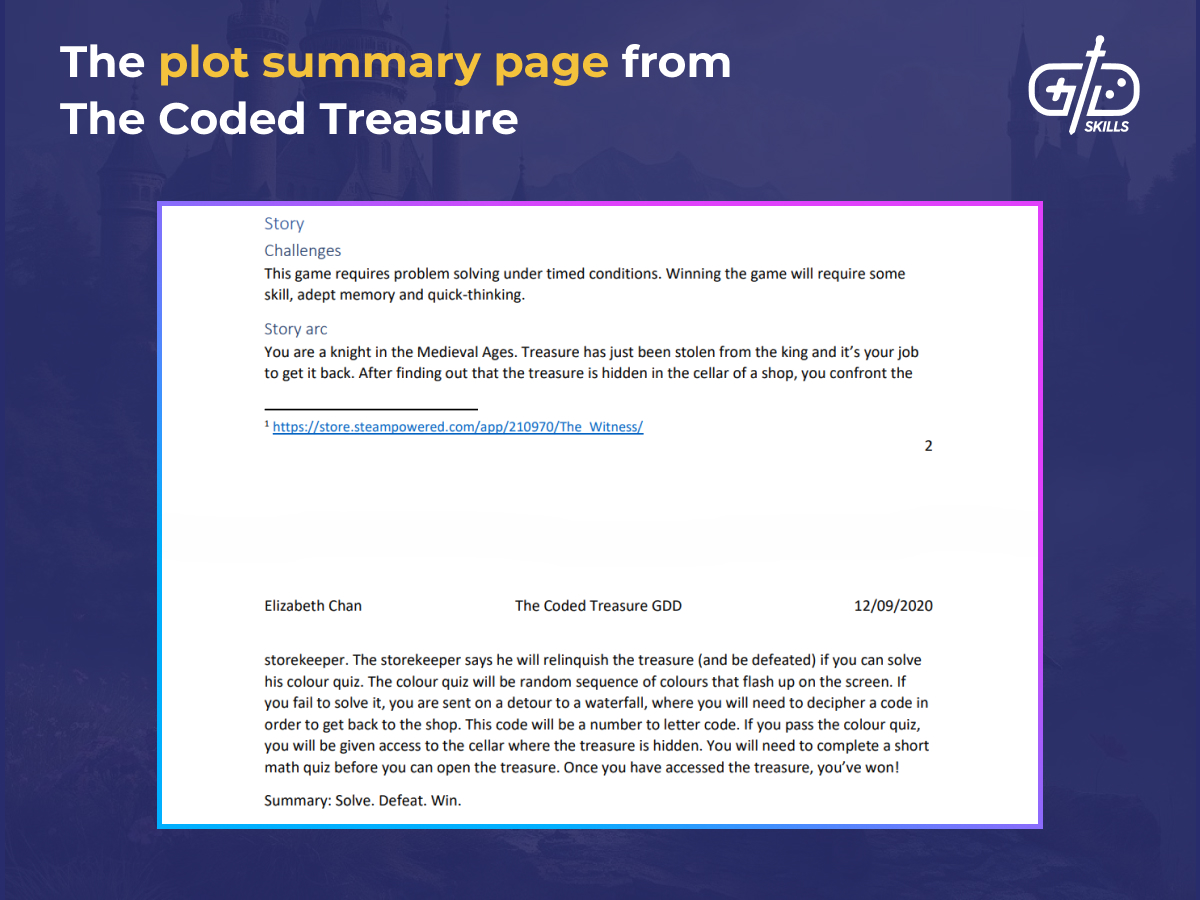

An example of a text-based game design document (GDD) is The Coded Treasure, a project created by students at the John Monash Science School. Though not as extensive as the documentation for some commercially released games, this GDD provides details on the key elements that must be outlined in pre-production documentation, like a title page, overview, narrative outline, and mechanics.

The title page of a text-based GDD must include the game title, an introduction/overview of the game, and details like the story premise, genre, and target audience. As The Coded Treasure is a student project, it’s lighter on these details than many commercially released games. Details that are typically present in the GDDs for larger projects include version numbers, studio details, confidentiality notices, dates of last revision, and, optionally, a tagline that summarizes the experience.

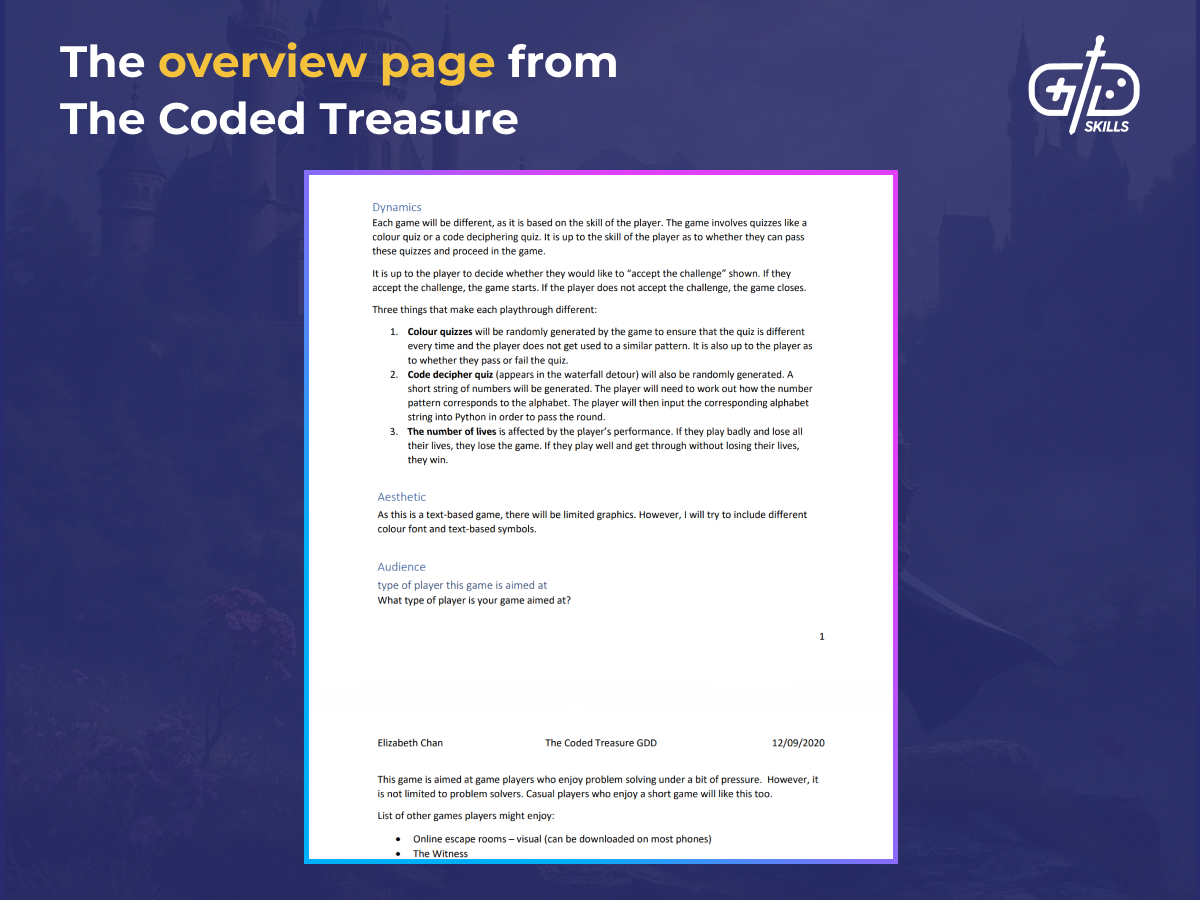

The game overview section of a text-based GDD gives the reader a high-level idea of what the game is about and what experiences are similar, without going into specific detail. Some overviews reference other games, some movies or TV shows, and others books or other media. The overview section must tell readers the genre and aesthetic, hinting at the objectives and challenges the player will face, but avoiding specific details about mechanics and interactions. A game’s unique selling point (USP) must be highlighted at this point to ensure investors and collaborators understand the principles underpinning the project.

The narrative and plot summary section of a text-based GDD must lay out the story behind the game and explain what the player does to progress. It must cover the setting, objectives, and hint at the challenges and antagonists the player will encounter. The story section of a GDD often resembles the text on the back of a book, giving a high-level overview without any spoilers. Commercial text-based GDDs sometimes include charts or node diagrams that explain the story-based choice and progression options.

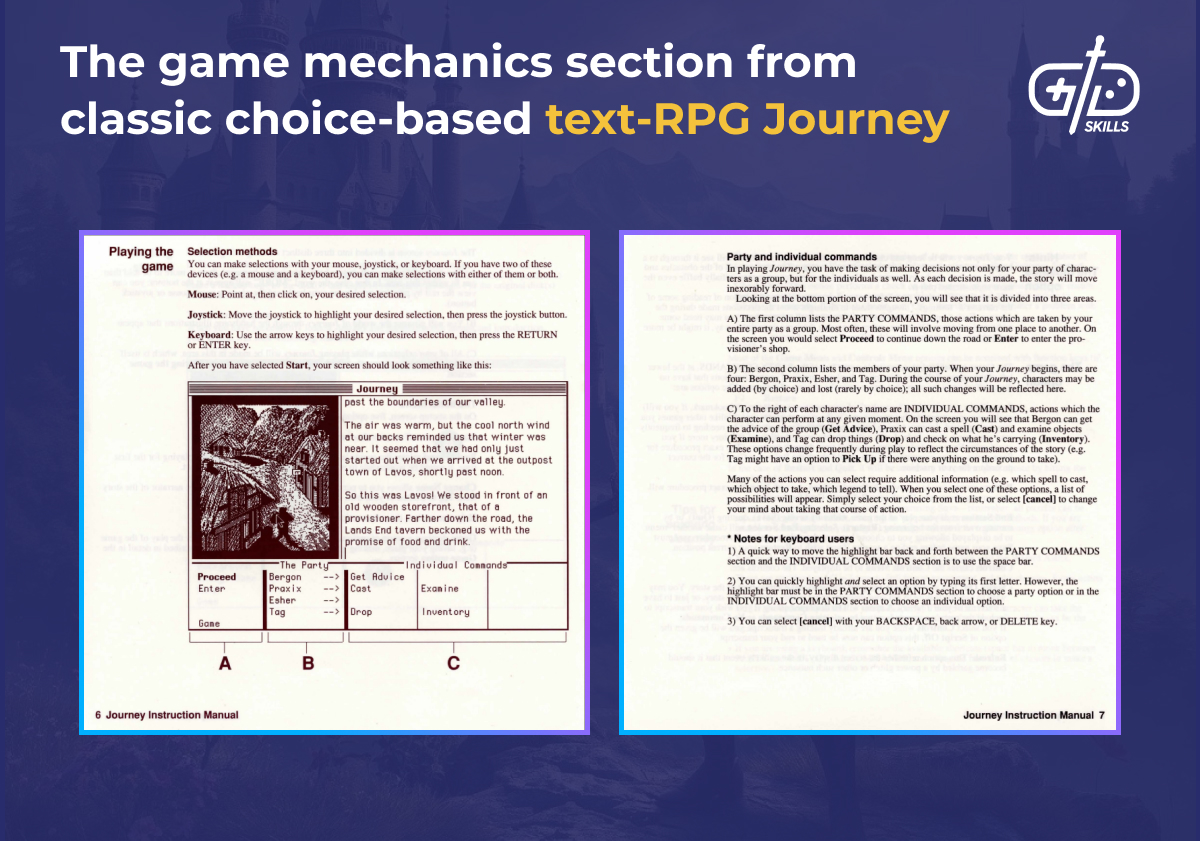

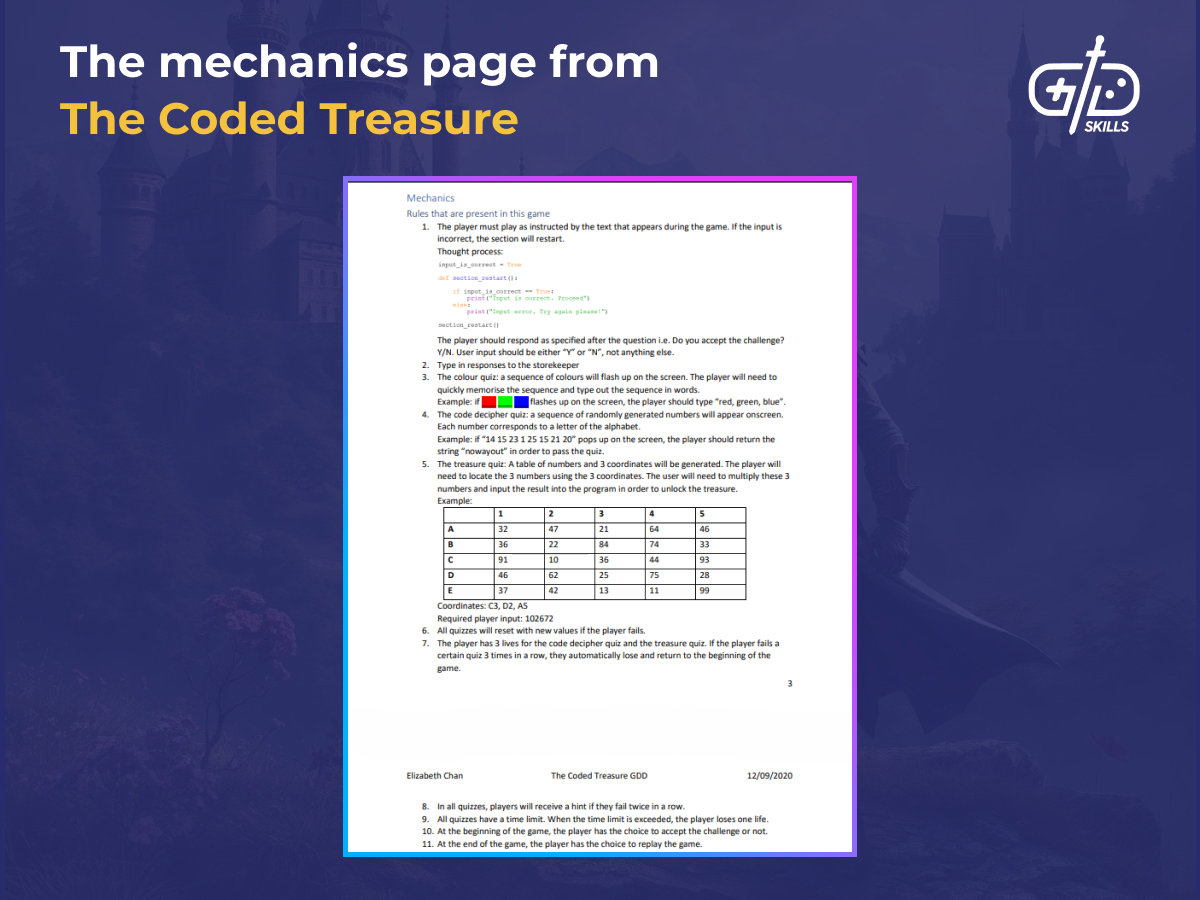

The game mechanics section of a GDD tells the player how they’ll interact with the game, and explains the variables and systems that exist. Because text-based games don’t feature physics or hitboxes, the mechanics section is typically shorter than with graphical games, where combat and exploration require greater detail. In the case of The Coded Treasure, the GDD details input commands and the rules governing quizzes. Player lives, timing systems, and scoring systems must all be explained in this section of the document.

Commercial or more ambitious text-based projects include sections on worldbuilding, setting description, location details, and character design details. This section details the type of setting: post-apocalyptic, sci-fi, fantasy, or other. The reader must get a feel for the tone of the game world through references to other media and descriptions of the game world’s specifics. The character section must outline factions, alliances, character archetypes, and rivalries. Setting out the character and settings clearly helps investors understand the project’s tone and ensures devs work toward the same vision.