Puzzle game design is the art of giving players challenges that result in an a-ha moment on completion. A successful puzzle is the result of extensive playtesting and exploration, and it doesn’t require advanced math skills or excellent deductive reasoning. A puzzle game starts with one idea, but designers spend time exploring the idea in detail and present the most interesting experiments to the player.

Puzzle games aren’t to be confused with games that happen to have puzzles like adventure games. Puzzles serve the exploration and story in an adventure game, and the core mechanic of the puzzles is explored in less detail.

Puzzle games start with an idea, so look for a mechanic that opens up many ways for players to interact with it. Learn the principles of creating a good puzzle game, how to pace out the levels, and create a UI that helps the player explore the mechanic to its fullest. Many resources are available online for getting ideas leveling up your puzzle design skills.

What are the principles of puzzle game design?

The principles of puzzle game design are a simple core mechanic which players explore in many different environments. The environments let players make mistakes and discover surprising new interactions. Design principles are the same in most puzzle games, but there are a few differences between the two largest categories of puzzle, procedural or handmade.

Procedural puzzles are puzzles that a computer’s able to generate. Sudoku is an example of a procedural puzzle. The difference in how players experience them is that new procedural puzzles don’t present new challenges. The skill required to beat one puzzle is the same skill required to beat another.

Handcrafted puzzles are built from the ground up with a unique solution in mind, and they are the focus here. The core mechanic players interact with has a unique twist, and designers make sure each level makes players think of new and interesting ways of applying it.

A puzzle game starts with one core mechanic. The core mechanic is simple so players immediately understand it. Each puzzle level layers on to the mechanic by adding constraints or new situations that make a seemingly trivial task difficult. Vocabulary quizzes aren’t very interesting, but add structure and strategy in the form of crosswords, and they become an engaging puzzle.

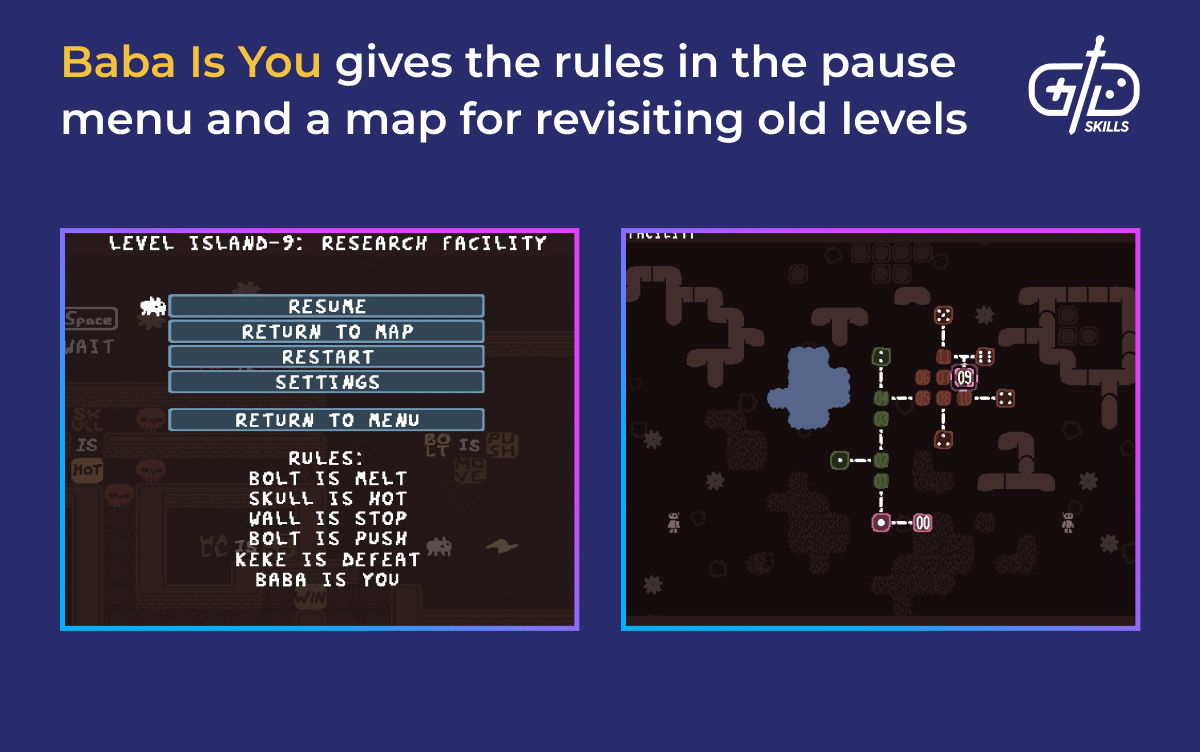

Each level asks players to realize a different way to apply the core mechanic, and letting players reset easily is essential for letting players reach the solution. Making mistakes is crucial for building mental models. Baba Is You and Snakebird, both block-pushing sokoban games, allow players to undo every action one-by-one, letting the player focus not on dying but trying new solutions.

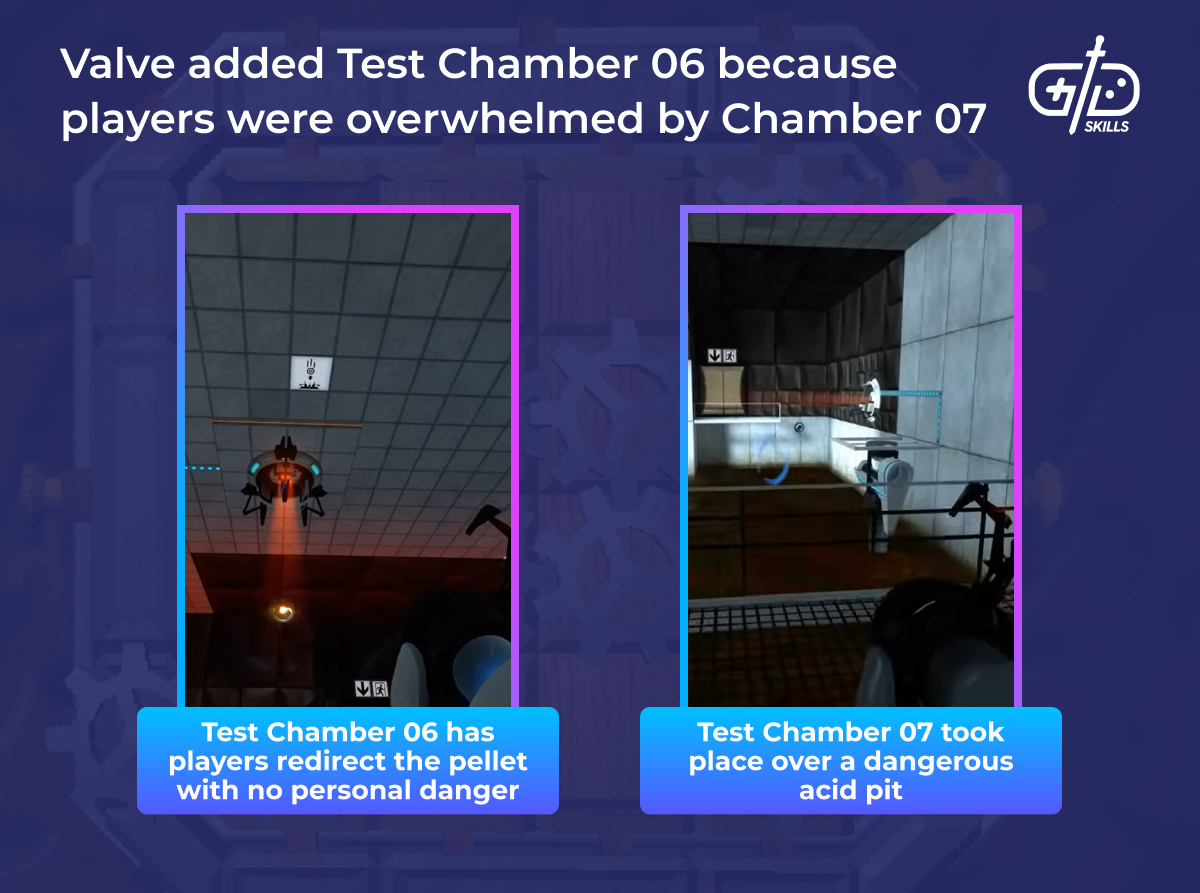

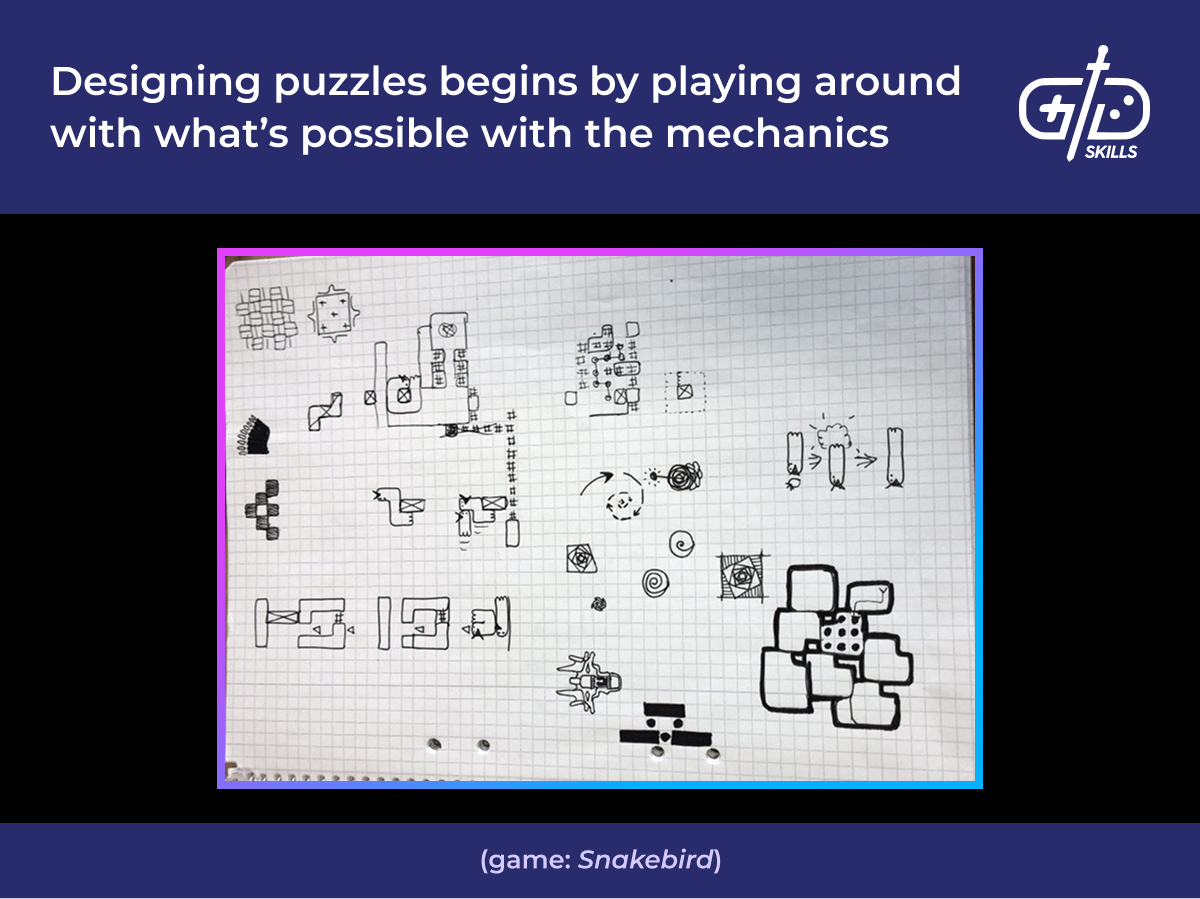

Level ideas emerge from playtesting and running through scenarios. The process is much like a sculptor chipping away to reveal a sculpture in a block of marble. Arvi Teikari, the creator of Baba Is You, said many levels ended up getting thrown out before even getting to playtesting. In a lot of scenarios, the designer realizes a level isn’t working properly just by stepping through it. The area either doesn’t create an interesting puzzle or asks players to use skills they don’t have yet. Valve added most of Portal’s levels to teach new mechanics as a result of confusion during playtesting.

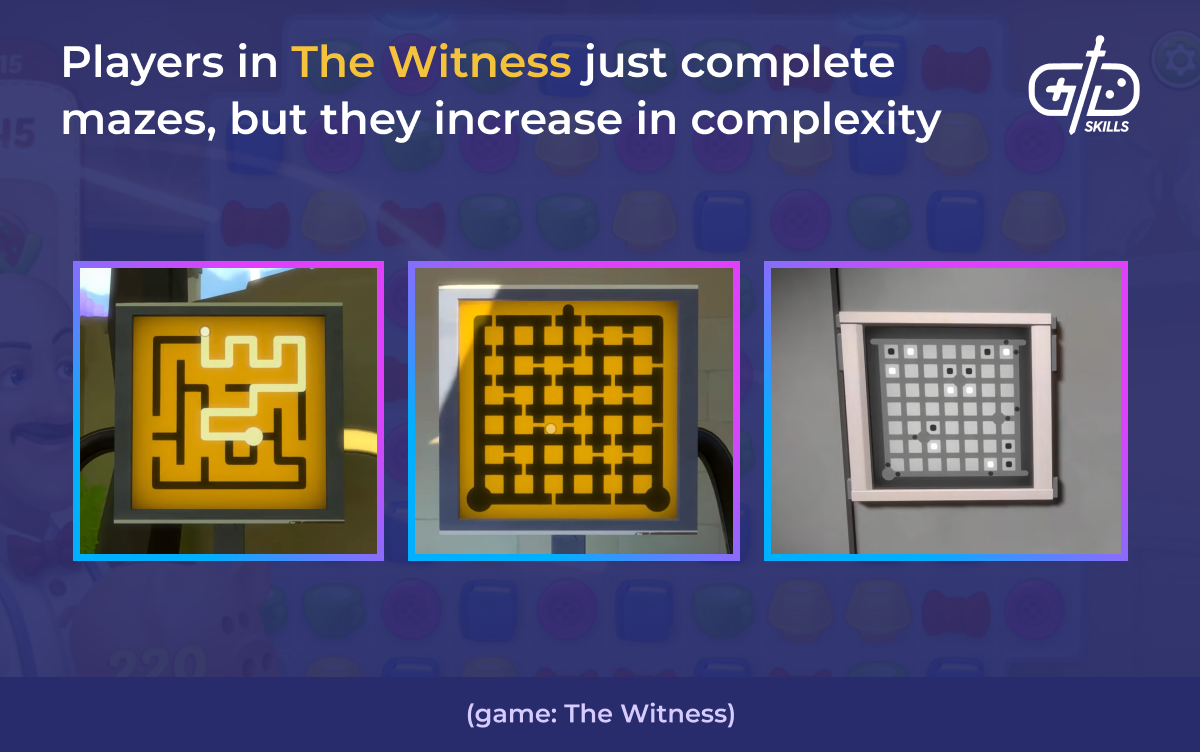

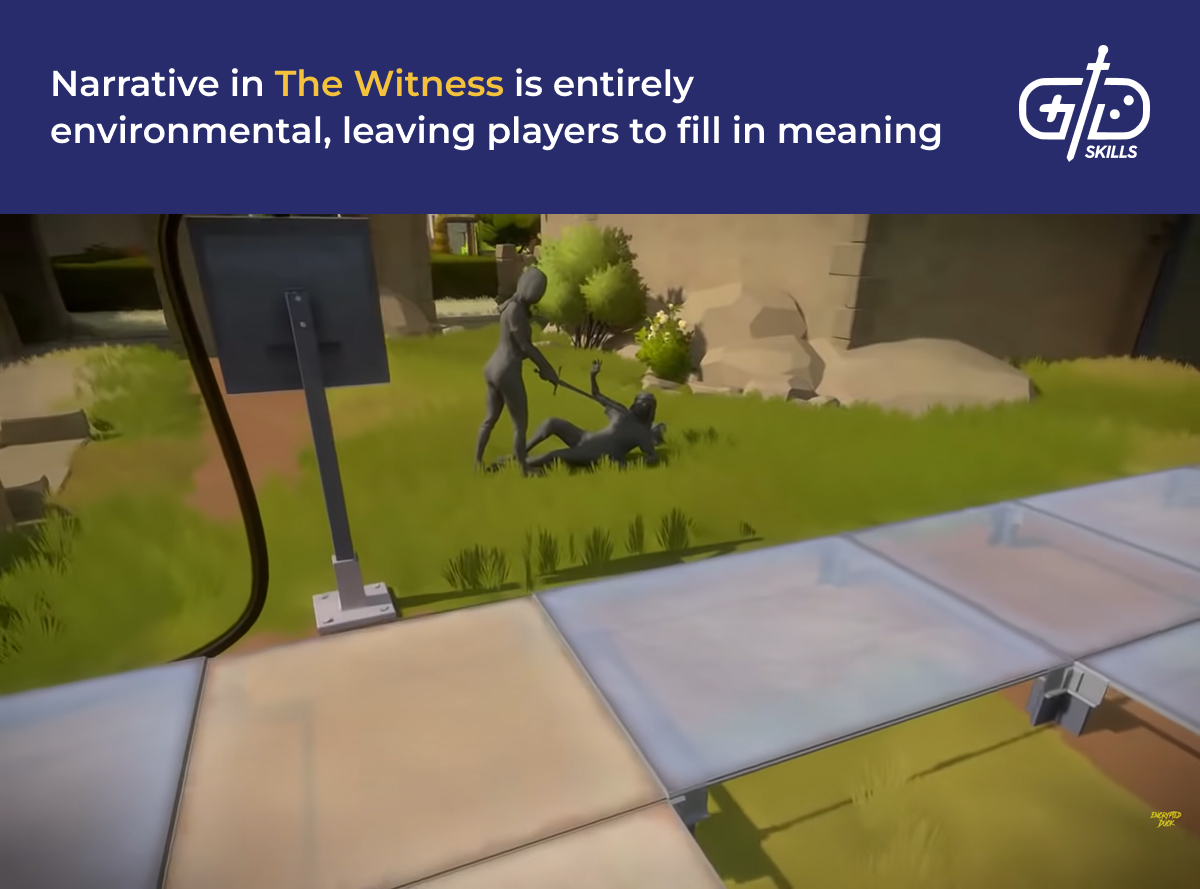

So much time is spent managing the difficulty of puzzles, however, that it’s easy to forget to challenge the player. Reducing the complexity of puzzles until every player feels confident on every puzzle takes any challenge from the game. Jonathan Blow says the problem is that what one player finds easy another player is guaranteed to find hard. The solution Blow took in The Witness was to make the game open world so players are able to move on to an easier puzzle if they get frustrated.

Narrative in puzzle games is important for providing context. Players are more curious about understanding the rules if they’re the rules of a living environment. Jonathan Blow in a 2014 interview with Gamasutra says: “the more that a puzzle is about something real and something specific, and the less it’s about some arbitrary challenge, the more meaningful that epiphany is.” Players are one step closer to reaching a specific goal when finishing a puzzle, like escaping Aperture Science in Portal.

How to design mechanics for puzzle games?

Design mechanics for puzzle games by thinking of mechanics that work in many different situations. Look to existing puzzle games for ideas or make sure ideas for new puzzle mechanics have enough flexibility to work in many situations.

Beginning with mechanics from existing, simple puzzle games is a good way to start. Games like block-pushing sokoban puzzles take only a few days to come up with, so playtesting is possible straightaway. Short puzzles are easy to make even on paper, and doing so saves resources before devoting time to coding a game.

Test a game mechanic idea before going forward with it. The game designer Ludipe suggests the “second level test” for determining whether to go forward with a mechanic at the beginning. A mechanic like a sliding block puzzle is fun at first, but it’s hard to imagine what the second level or even third level is going to add. If a designer isn’t able to imagine a variety of situations for a mechanic, it’s not likely to hold up for a whole game.

A mechanic like rewinding time in Braid meets the second level test because there are so many interactions that are able to emerge from the base concept. Jonathan Blow, the creator, spent time playing around to see what interesting situations emerged. He saw that, if certain platforms moving are immune to rewinding, the player will be over empty space (instead of the platform). Now Blow had another puzzle to introduce to the game, a specific task for the players to realize they needed to do.

Playtest, playtest, playtest as soon as there’s a mechanic that looks like it’s going to keep player interest. Playtesting tells a designer much more about the mechanics than playing around. The latter is an endless source of base ideas, but ideas are cheap. Altering the level is difficult without input from players, since the number of moving parts and extra noise a player is able to handle is less than the designer who has complete control of the game.

How to design levels for a puzzle game?

Design levels for a puzzle game by playing around with the solution first. Puzzle level design starts with one interesting idea that designers overlay with a series of obstacles, false solutions, and artwork. Then designers work backwards to make sure they appropriately teach the player the core mechanics correctly and slowly build to harder levels, considering how to vary the pacing the whole way.

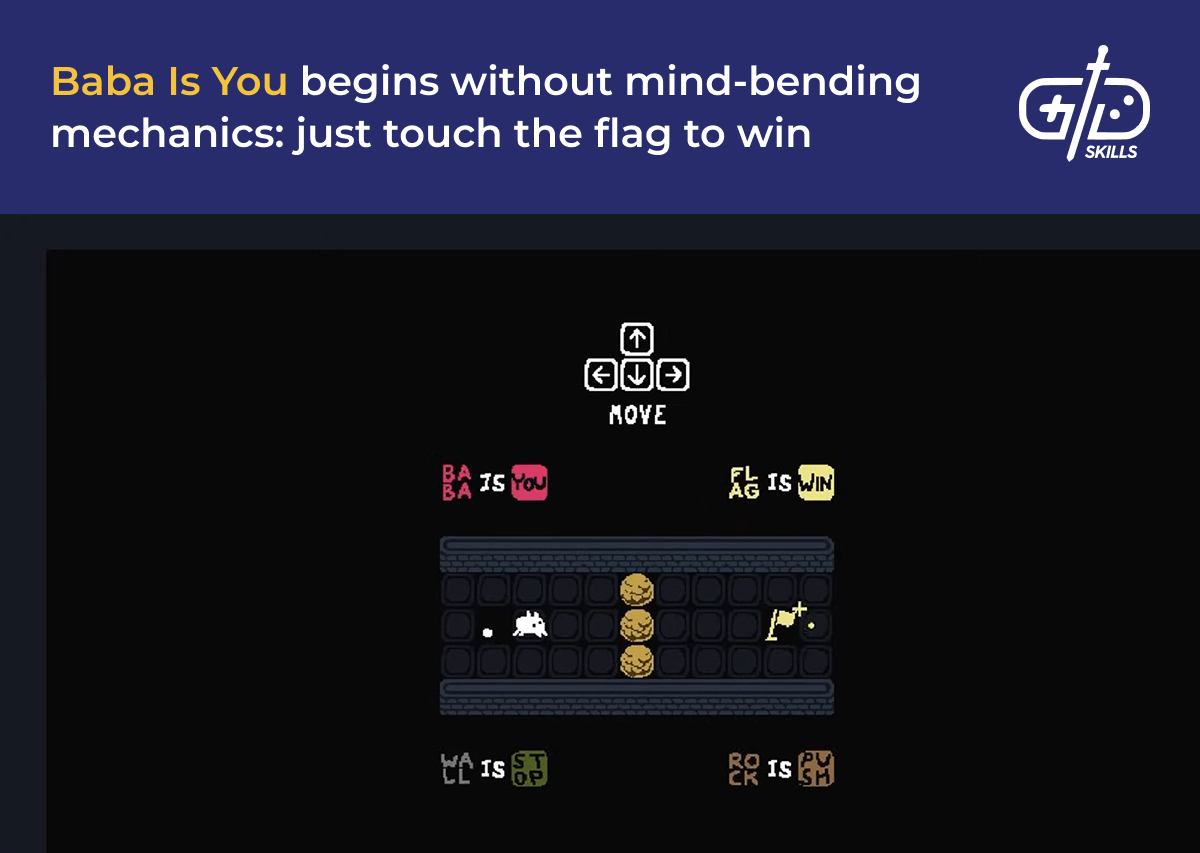

Each level in a game teaches players a new skill until they have the ability and confidence to tackle tough problems. Baba Is You is a case study in introducing players to the basic tools they need for later puzzles. The player solves puzzles in Baba Is You by pushing blocks. The twist is that the blocks are actually the game rules. The blocks WALL, IS, and STOP make the walls have collision when pushed together. The premise is a bit mind-bending and unintuitive, so the game starts without modifying rules. Players in the first level simply touch the flag to win, which is a rule visible on the screen.

Each level brings players to a new realization that becomes a tool in the player’s toolbelt. The player isn’t able to complete the second level without realizing they’re able to push blocks to break rules or push them together to create them. The solution to the third level is to create the combination “WALL IS YOU”: players realize they’re able to control other objects by modifying the rules. The fourth level is solved through the rule “ROCK IS WIN”, meaning players learn they don’t even have to touch a flag to win. After the first region of the world map, players use all the skills they’ve learned to solve increasingly difficult puzzles.

An effective tutorial is invisible; players are having too much fun solving puzzles to notice. Portal extends the tutorial over nearly all the test chambers, meaning players enter the final stage of the game having learned every core skill over a couple hours of play. Orange and blue portals, momentum through portals, enemy turrets, the incinerator, all key mechanics have been introduced before the final segment of the game.

Valve makes sure players learn in Portal by guaranteeing only one solution in each of the early puzzles. Valve removed any creative alternate solutions through repetitive playtesting. Players still weren’t understanding portals in the second level and onward, so Valve added Test Chamber 01. Test Chamber 01 requires players to walk through 5 portals in a specific order to complete the puzzle. There is no brute forcing the puzzle and passing by mistake. After Valve added the level, they eliminated most issues with players failing to understand portals for the rest of the game.

Level ideas start with an interesting rule or mechanic. Arvi Teikari begins levels with an interesting win condition. He asks a question like, “What if players teleport the rules around to create new ones?” Teikari then works on a level that guides the player toward that goal. As he plays with it, he realizes whether there are unintended ways to complete the puzzle, or if it’s too trivial, and he adds new obstacles and challenges.

Most of the level ideas plotted out never make it into the game. A game like Baba Is You presents only the best puzzles that emerged from the development process. Some puzzle ideas don’t become fun after tweaking and get scrapped. Several rule blocks in Baba Is You, such as “STICK” and “SAFE” were too difficult to program or weren’t fun and got scrapped.

Keep the end of the puzzle in sight from the very beginning. Players must think about how to complete a puzzle, not also what to complete. Having a clear end in mind lets the designer play with expectations. The solution at first seems obvious, but players hit an obstacle which makes them realize it isn’t as simple as they thought. Each step of the way, the player slowly lowers obstacles until they reach the solution.

A hook for a level doesn’t have to be a new mind-bending rule. A simple twist on the environment or context is enough in some cases. Farm Heroes Super Saga varies levels by adding wind that blows pieces in a different direction than normal. Players in the final stage of Portal escape from the last test chamber, running free through the innards of the facility to look for the mad AI that’s trying to kill them. New environments in this case raise the intensity, putting players in a new, uncontrolled space.

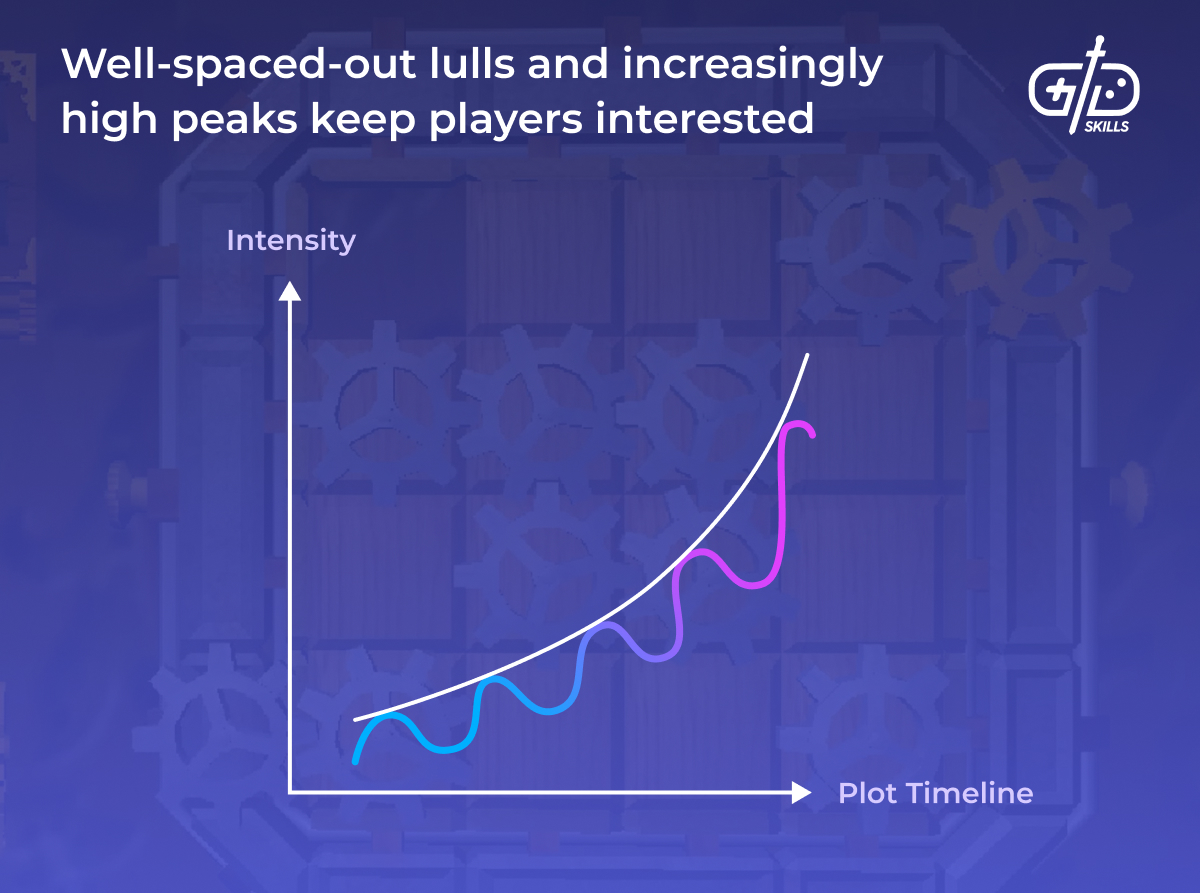

Don’t forget to vary the challenge throughout the game. Some players always find one puzzle easy and others hard, so variety ensures there’s something for everybody. A mixture of easy levels between harder parts serve a purpose for skilled players as well. Players get a break, their expectations about what comes next are challenged, and they have the chance to show their mastery over the game. A forward march to harder and harder puzzles is challenging but predictable.

Timers or time-sensitive challenges make a game more dramatic without significantly changing a level. Bejeweled gets two game modes for free, with the original game only including classic and timed modes. Portal defaults to untimed challenges, but the designers recognized they are effective for making a puzzle more dramatic. They added time-sensitive moving platforms to the last test chamber to create a climactic moment out of a series of otherwise easy challenges.

Playtesting with several types of players is essential. Many of the earliest puzzles created in the design process are too complex, since designers start with creating the most interesting scenarios they’re able to envision for their new mechanic. Savvy players who find all the alternate strategies are just as important for tweaking levels as “your mom” playtesters who’ve never played games before. The former makes sure the player must use the right skills to beat a level, and the latter tells designers where they’ve failed to teach them. The first level designed for Snakebird moved up to level 9 by the end of development.

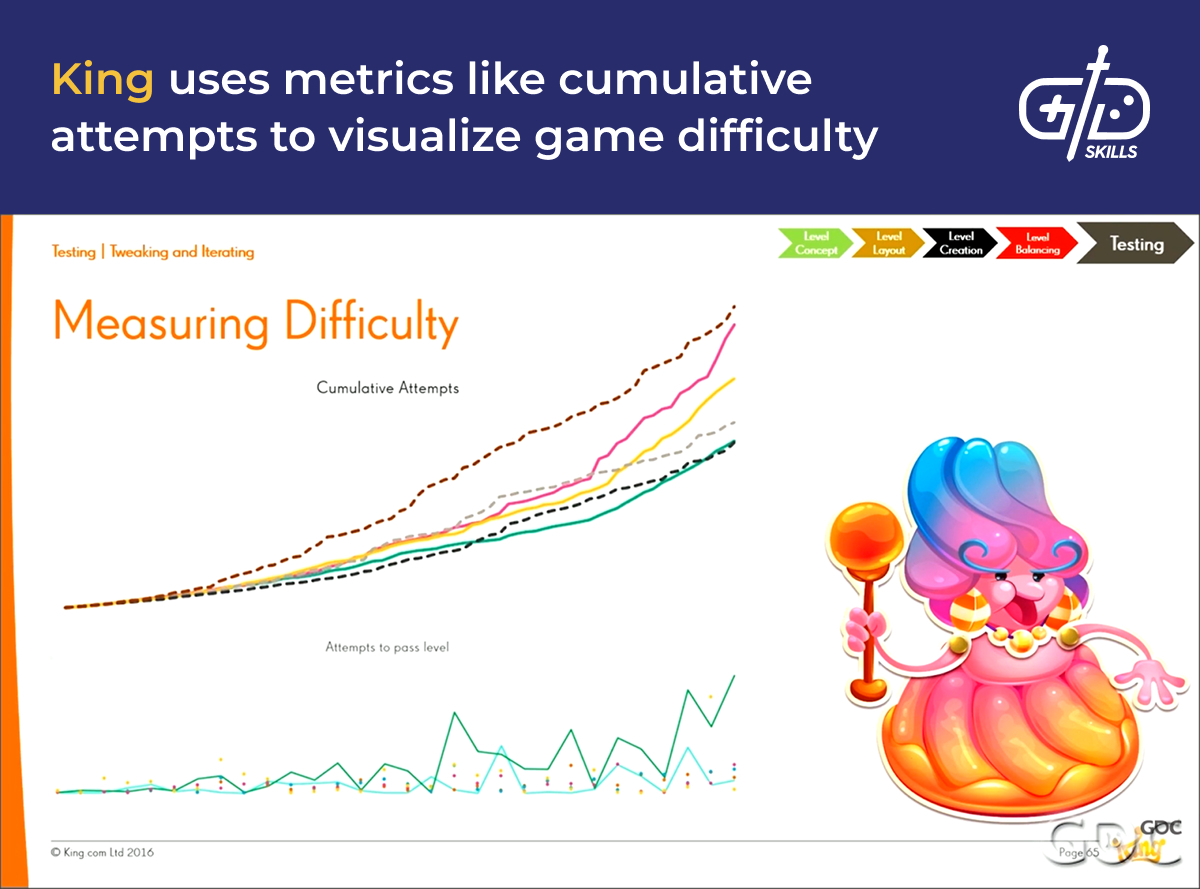

Gathering data in the casual game market before and after release is common practice for quality control. A released game has thousands or even millions of new data points for refining the gameplay. King keeps track of several types of data on games like Candy Crush Saga: lifetime number of moves used, percentage of players that made it to each level, what level players quit on and didn’t return. King uses the data to identify problem levels and evaluate adjustments.

Playtesting from other expert puzzle game designers in addition to the unspecialized public is desirable. Game jams are an opportunity to prototype a quick puzzle game idea and see what other experienced developers have to say about it. Arvi Teikari had Jonathan Blow and a crew of all-star puzzle game designers playtest his game. Levels at the casual game developer King don’t go to the first level of QA until other designers have playtested it.

How to design UI for a puzzle game?

Design UI for a puzzle game which is readable but unintrusive. The menus, level selections, pause menus, and HUD are key elements of the game but not the star of the show. The ability to revisit old levels, read up on old mechanics, and revisit the tutorial are important features to consider for a puzzle game.

Game UI at minimum communicates the current state of the puzzle to the player. Computer games have an edge over pen and paper puzzles in this regard. Sudoku gives the player no assists or feedback, unless by chance there’s an answer sheet, but a computer says straightaway whether a move is valid. A deep dive into visual design is out of scope here, but aids are important since players are at different skill levels and play games on and off. Bejeweled avoids any friction with the player at all by adding a hint system, where players reveal the next valid move at the click of a button.

Information taught to the player ought to be available throughout the game, through the UI or otherwise. Players who stop playing the game know they’re able to pick it back up later. Portal does this without UI, teaching and reteaching throughout its short runtime. A level navigation interface where players are able to replay old ones is helpful, especially if the tutorial levels are separated like in Baba Is You. A menu for reviewing rules or abilities is enough in cases where players just need something to prime their memory.

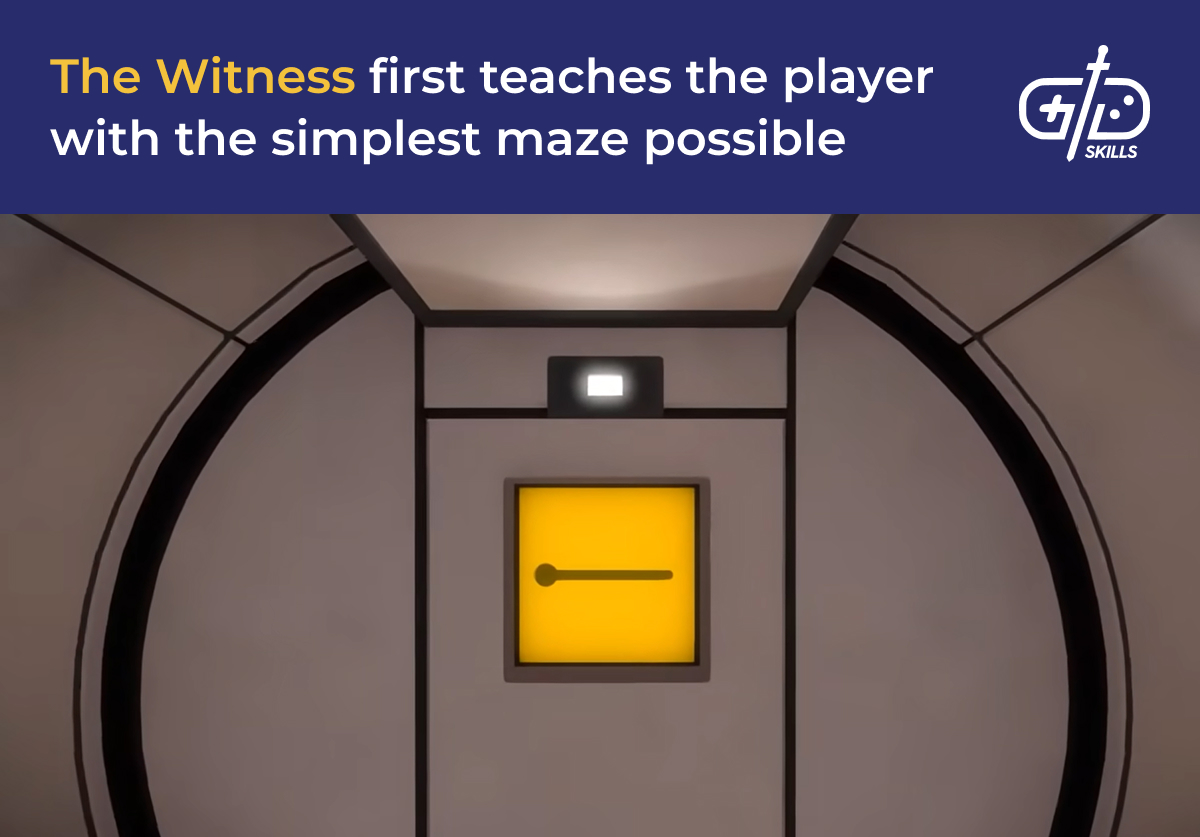

A well-designed puzzle game therefore needs hardly any UI at all. The Witness teaches its gameplay without any text. The core mechanic is simple: solving mazes. Players don’t need to be retaught how to play, and the freely explorable open world makes navigation and revisiting puzzles the same activity.

What are puzzle game design ideas?

Puzzle game design ideas are present not only in other puzzle games but in everyday activities. Children challenge themselves to stack blocks into towers and build castles on the beach all on their own. Block puzzles, word puzzles, and physics puzzles are major categories to look at for ideas.

The way humans use pattern recognition to navigate the world itself generates ideas for puzzles. People are wired to look for patterns, sort objects, spell words, and solve problems. We exercise the same skills when we scan for the right jar of tomato sauce at the store or organize bookshelves. Even Baba Is You emerges from two basic principles: pushing blocks around and the meaning of simple sentences.

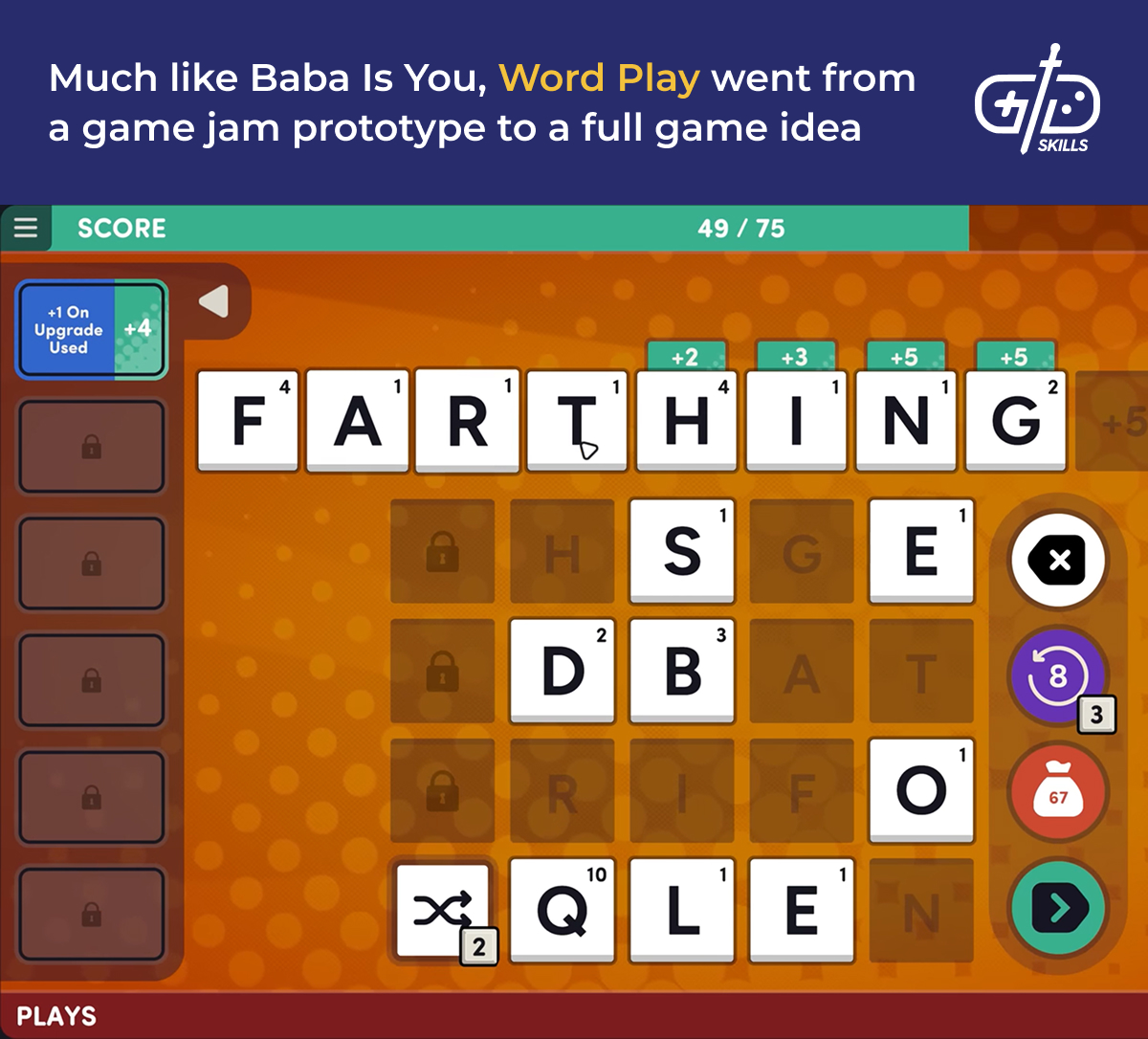

Mark Brown documented his process for creating a word puzzle game in 7 months. Game jams give designers a short window to create with an open-ended prompt, and the prompt “Bending the Rules” inspired Brown to combine Balatro with Scrabble. Puzzle games have a simple and consistent core mechanic: in this case, placing letters to spell words. Creating games like this from scratch is easier than a shooter or a platformer, so getting a playable game in front of audiences quickly is much easier.

Brown began development with streamlining the basic experience before iterating on the perks and other gameplay systems. Making sure the premise is fun at all to begin with ensures it isn’t a waste of time. Brown first added the ability to shuffle tiles and made sure dragging and dropping tiles felt right. Only afterward did he add more perks and modifiers like “a word this round must have 6 letters”. The playtesting phase is where many abilities came to fruition.

Block pushing is a fertile place for puzzles in dedicated puzzle games. Rush Hour is a board game version from the 70s. Players drag cars along a grid until they’re able to slide each one out of the exit. The advantage on a computer is an undo button, an important quality of life feature. Challenge of Sokoban and computer versions is that a player character pushes the blocks around, so pushing the wrong block into a corner where players aren’t able to push it back out might make the puzzle unsolvable.

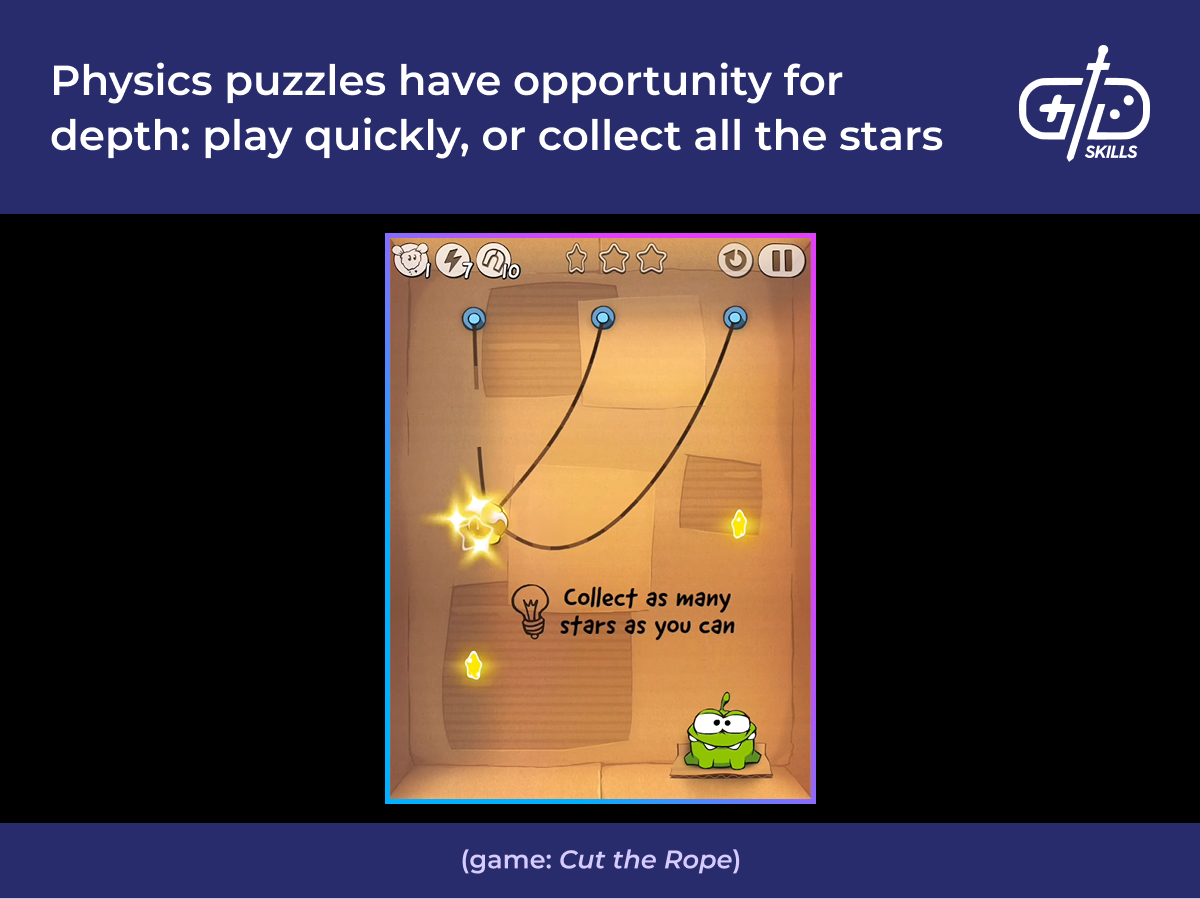

Puzzles with realistic physics are common and also simple. Jenga doesn’t take more than a few moments to explain: pull out pieces and don’t let the tower fall. The advantage of this style of game is that players already have an understanding of how slings, ropes, and blocks work. A core loop of swiping to cut strings and pulling to launch birds is intuitive for players using a touch screen.

Puzzle game narratives emerge after gameplay. Narrative is secondary to gameplay in all games, but puzzle games especially don’t work when a designer has a story in mind before the mechanics. Valve originally intended Portal to take place in areas just like the Half Life universe, grungy industrial areas filled with props. Playtesting showed the visual noise was excessive, since players had no way of knowing at first glance what is relevant to the puzzle and what isn’t. The game moved to a lab environment to keep the gameplay focused, which ultimately guided the direction of the final story.

Ideas sometimes emerge from the playerbase themselves. The wacky and unintended flying machines that players created in Breath of the Wild encouraged the designer Hidemaro Fujibayashi to add the Ultrahand to Tears of the Kingdom. The Ultrahand is used for solving puzzles, but is also more of a creative tool. The Ultrahand allows players to pick up physics objects and also create contraptions by gluing wheels, fans, and objects together. Such an idea is difficult to implement without extensive playtesting, but the creativity of players in the previous game showed it was likely to be interesting and worth iterating on.

What books are recommended to learn puzzle game design?

Any game design book is recommended to learn puzzle game design. Puzzle games in pen and paper have existed for as long as the pen and the paper themselves, so experts in the field have much to draw on to create puzzle game guides. The general principles of pacing, playtesting, and designing mechanics remain similar to other games, though, so check out the classic game design books for more information on how to turn a puzzle mechanic into a fleshed out game.

Puzzlecraft is a book that covers puzzles in general, not specifically in video games. Breaks down puzzles into types, with examples. The authors are both puzzle veterans. Mike Selinker creates word puzzles for print publications, and Thomas Snyder creates logic puzzles and sudoku variants. The authors are experienced, but the book only has enough space to treat each puzzle type briefly.

Challenges for Game Designers includes challenges that don’t require coding but get the reader thinking about game design problems. The book is heavily project based, asking readers to complete a number of projects to learn rather than spending the whole time with their nose in the book. Brathwaite is a game designer who has worked on games since the 1990s. Ian Schreiber has been a systems designer since 2000 for games on various platforms (mobile, PC, and online).

Rules of Play discusses games at large, including video games, sports, and board games. The book is heavy on theory, and isn’t the same practical guide as the other books here. Katie Salen is a professor at the University of California Irvine and worked her co-author Eric Zimmerman at gameLab, a New York game studio best known for Diner Dash.

The Art of Game Design gives lenses for thinking about how to design a game. The lenses encourage designers to think from the perspective of players, since they’re the ones who’ll pay money to play the game. Schell’s work isn’t a step-by-step process for making a game, but several ways to approach the problems of game design. Schell was a designer for Toontown Online and works in game design to this day.

Game Mechanics teaches readers how to create and evaluate prototypes. The game drills down on how to develop mechanics and is quite dense. Reading the book from beginning to end isn’t helpful for all readers: keeping it handy as a reference is an effective way to use the book. Joris Dormans co-founded the indie studio Ludomotion and is a professor at Leiden University. Ernest Adams worked on the Madden football series with EA and founded the IGDA.

Game Design Workshop provides a series of steps, exercises, and frameworks for thinking about prototyping and designing games. An advantage of the book is the number of practical exercises it asks the reader to work on over the course of the book. The author is the creator of the indie game Walden, which she created as a student at UCLA.

Where to find a puzzle game design template?

Find a puzzle game design template online to quickly prototype ideas. Puzzle games have a simple foundation, so it’s easy to prototype an idea in Unity or Unreal, but online asset stores have many templates for those looking to get started without coding.

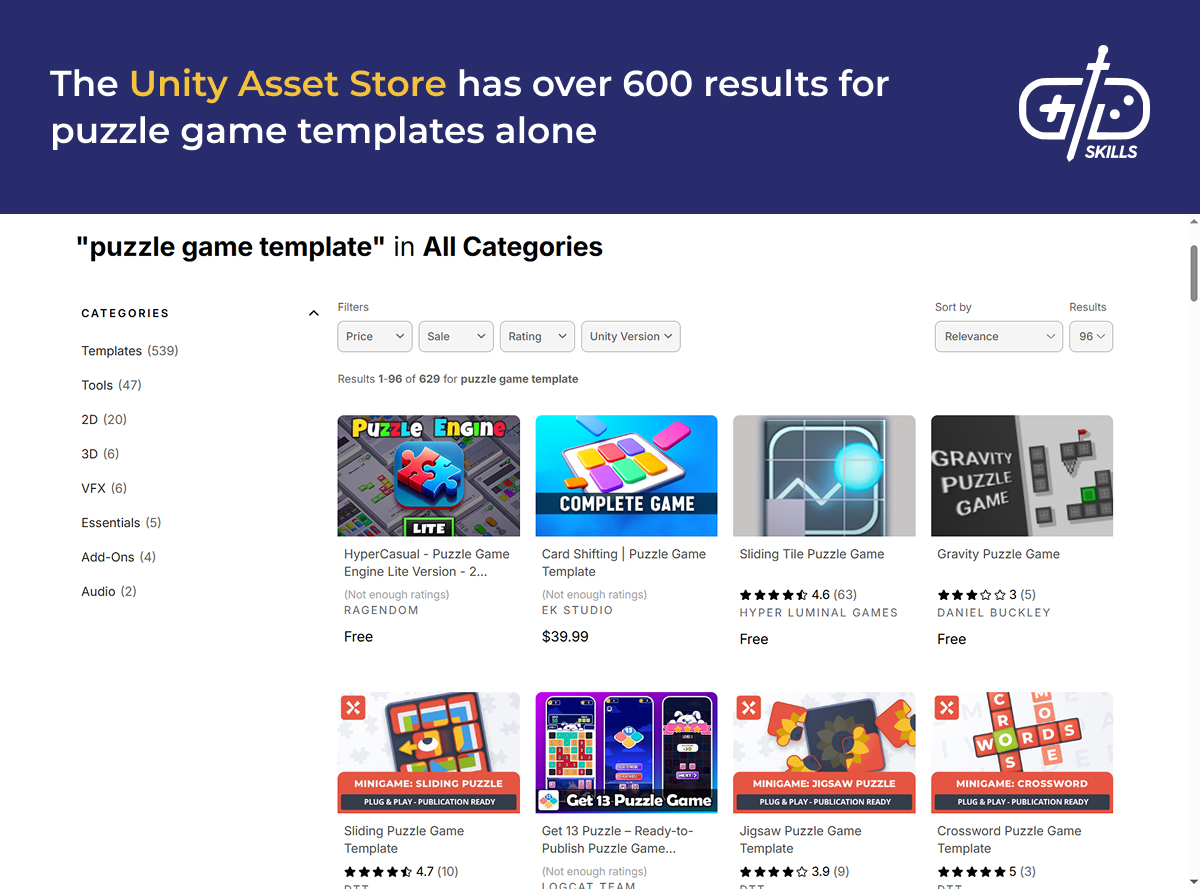

The Unity asset store has resources for common puzzle game types. Simple puzzle types such as sokoban games and crossword templates come up high on the list in the search. Puzzle games tend to be simple and easy to create, but templates are a good place to start for those without a lot of coding experience.

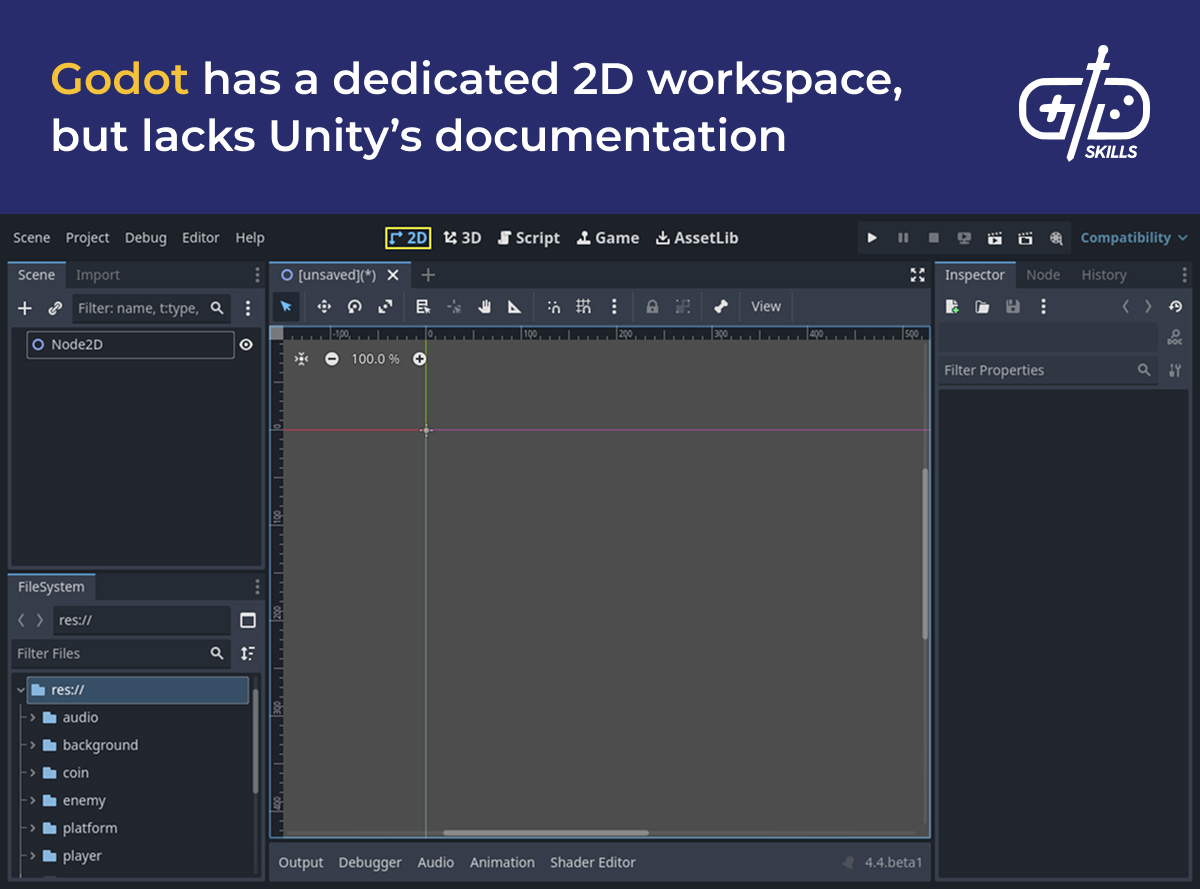

Popular game engines come equipped with built-in systems suitable for creating puzzle games from scratch. The rigid-body systems in Unity and Unreal are required tools for a physics-based puzzler. Puzzles in 2D are common, and Godot features rigid body physics for its 2D editor as well. Unity and Unreal are 3D engines, but Unity has a number of specific 2D sprite, lighting, and tile map editors for making the process more intuitive than Unreal.

Hypercasual puzzle games are puzzle games with simple mechanics that small teams are able to quickly iterate on. Templates aren’t necessary for the genre, but there are a number of communities online discussing their ideas. The Hyper Casual Jam on itch.io is one place to get work in front of other designers. The subreddit r/hyper_casual_games has an intro to hypercasual jargon and more resources for designers who aren’t sure where to start.

What is an example of a puzzle game design document?

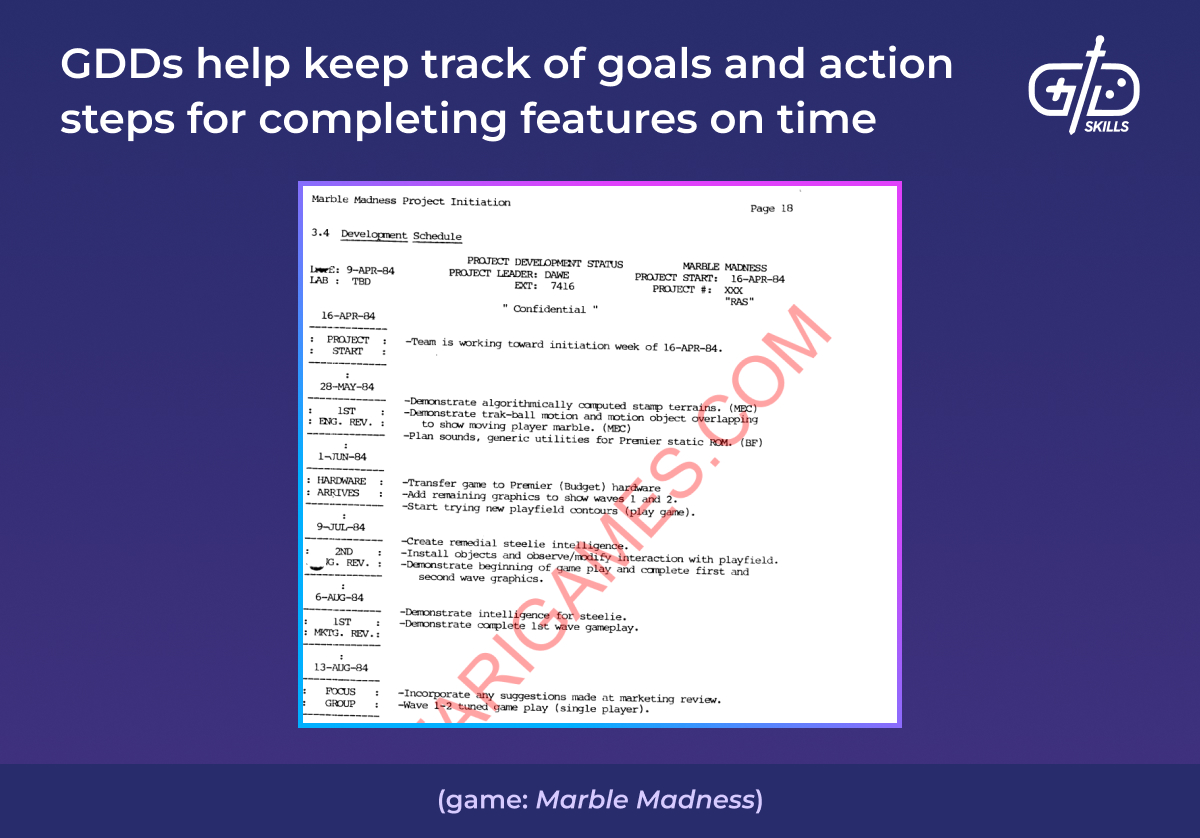

Examples of puzzle game design documents exist online for classic games such as Portal’s first prototype and Marble Madness. Marble Madness is closer to a platformer than a puzzle game, but it bears similarities to the genre and the GDD demonstrates some best practices in creating a GDD. The two GDDs are a few decades old, so look at a generic template for getting started.

A GDD contains a concise explanation of the core gameplay, the obstacles the player will face, and the target audience. GDDs keep teams on the same page. The whole team must be in sync for the project to reach the finish line. Designers must have an idea of what effect they intend their mechanics and systems to have on the player so they know whether the implementation was successful. Artists and programmers need a set of tasks to work on, a guide that says the game is complete after X Y and Z are done. The plan changes, but having an idea of the most important tech to implement and milestones in the project keeps development on track.

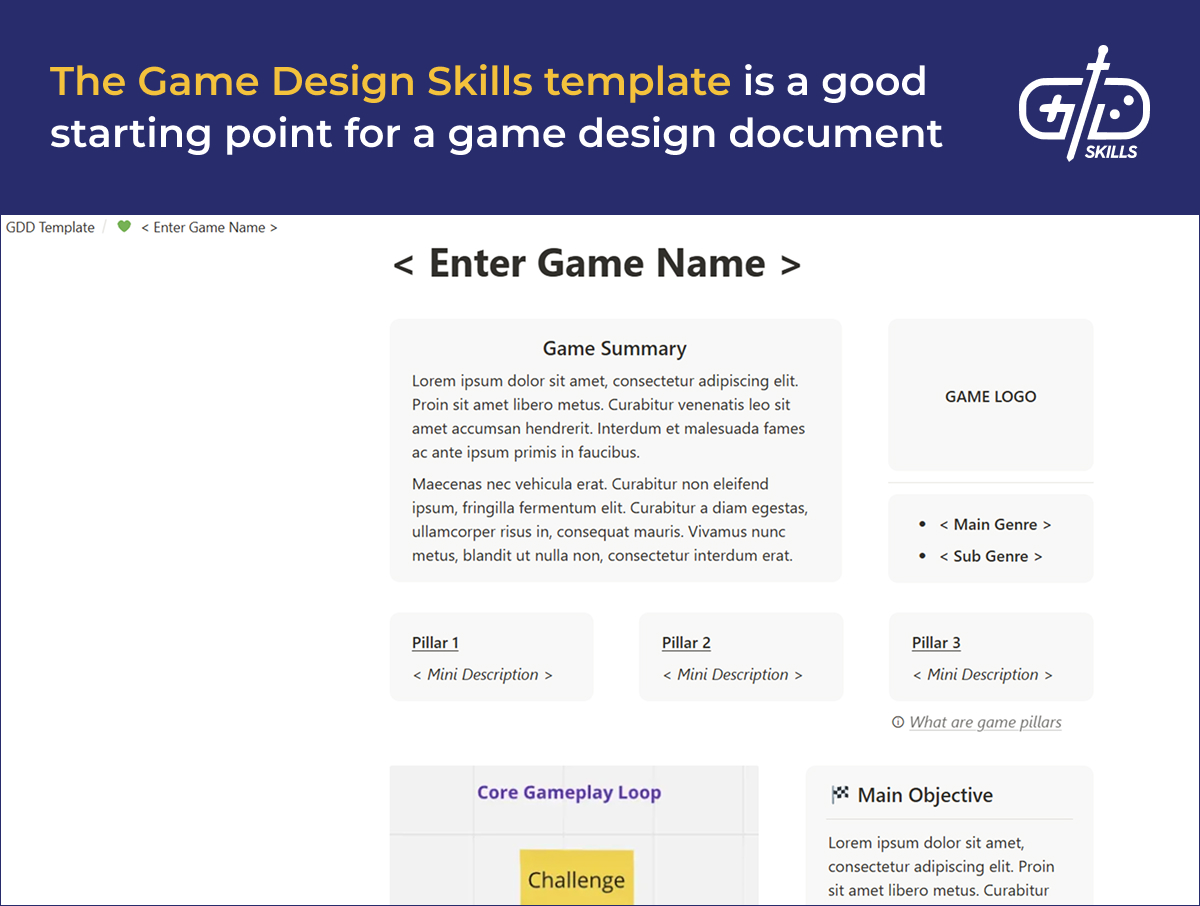

Puzzle games need a bible of mechanics and systems so designers know the toolset. King keeps spreadsheets where each level and its mechanics are documented, making sure new designers preserve the correct pacing. The Marble Madness GDD does better than a spreadsheet: the game lists all the possible obstacles with pictures on pp. 5-12. Our GDD design template has templates for a main GDD and its attached feature documents and has room for describing mechanics in detail.

The student design document for Narbacular Drop, which later became Portal, is another example available online. The document lists all the actions the player is able to take, as well as what important actions aren’t in the players toolset (jumping and pushing objects). The portals in Narbacular Drop were a brand new technology, and the GDD lists out features and detailed descriptions of the rendering solutions. Each section in the following list comes with a point-by-point description of the features and file formats involved in bringing the feature to life.

- UI

- Controls

- Graphics

- Audio

The Narbacular Drop GDD was also a tool for assigning tasks. The purpose of the feature descriptions in each section is to limit the scope of the project and assign roles. A video game doesn’t come together by magic, believe it or not, but is a complicated set of software that requires planning. The task list and deadlines give the team realistic goals and tells the team whether the project’s on track.

There’s only so much room here to talk about puzzle games, and there’s so many out there! Have you done design work on any puzzle games yourself? Do you have any more principles of puzzle game design in mind? Do you know of any more game design templates and documents? Let us know in the comments, and please give us your feedback on the article!