Casual games are simple experiences that appeal to a general audience. The casual market entices non-gamers with simple, addictive gameplay that’s cheaper to experience than hardcore games. Designers enter the casual market for similar reasons, because casual games are quicker to create: a small team is able to create a profitable game in a matter of months.

Learn about the fundamental principles of casual games: simple verbs, teaching mechanics to players clearly, and where to find inspiration for these mechanics. The casual market shares gameplay loops with the hardcore industry, so see what general books and resources are also applicable to casual game design. Look at the end for online assets, monetization models, and documentation strategies to get development started.

What are the fundamentals of casual game design?

The fundamentals of casual game design are a basic core gameplay loop, accessibility to non-gamers, and, increasingly, a free-to-play (F2P) business model. Casual games tend to be mobile games, since that’s where players outside the hardcore world are able to access games. Certain monetization strategies have become dominant since the casual market offers a quicker turnaround – ad revenue, in-app purchases (IAP), and, occasionally, premium paid games.

Casual games have simple core actions that are instantly understandable. Players are limited to one or a few actions they do on their device already: click, tap, swipe, or tilt. Puzzle games are common since they limit a player’s actions to dragging or swapping pieces. The rules of the game constrain the player enough that the only valid moves result in successful gameplay. Mimicking actions the audience is already familiar with takes advantage of players’ prior knowledge as well, which reduces what players need to learn. Super Mario Bros. uses jumping, something anyone’s able to do, as its core verb.

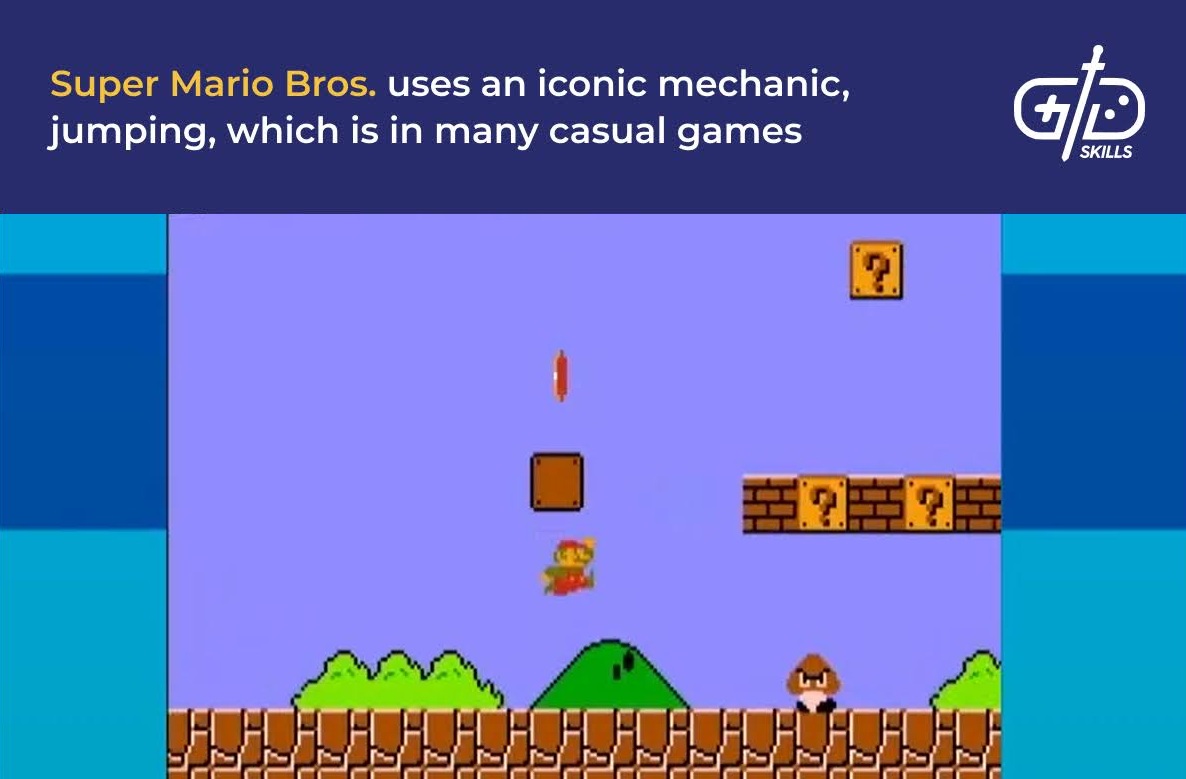

Casual games range from paid, polished, linear experiences to F2P titles with in-app purchases. Most popular casual games are indeed F2P mobile games, since everyone has a cell phone. Paid content breaks into the mainstream casual market from time to time, however. Balatro is a roguelike, which is typically a hardcore game genre, but has seen a successful release on mobile as a paid (premium) game. The concept of creating poker hands is familiar to general audiences, and the repetitive gameplay gives players opportunities to improve.

Games are a business, and monetization strategies factor into fundamental design decisions. Casual game designers create simpler products, but in a very competitive market. Casual game level designers tweak levels according to user data at a much more detailed level than hardcore game designers: player retention rates, install rates, and percentage of game completion are only a few stats that factor into design decisions.

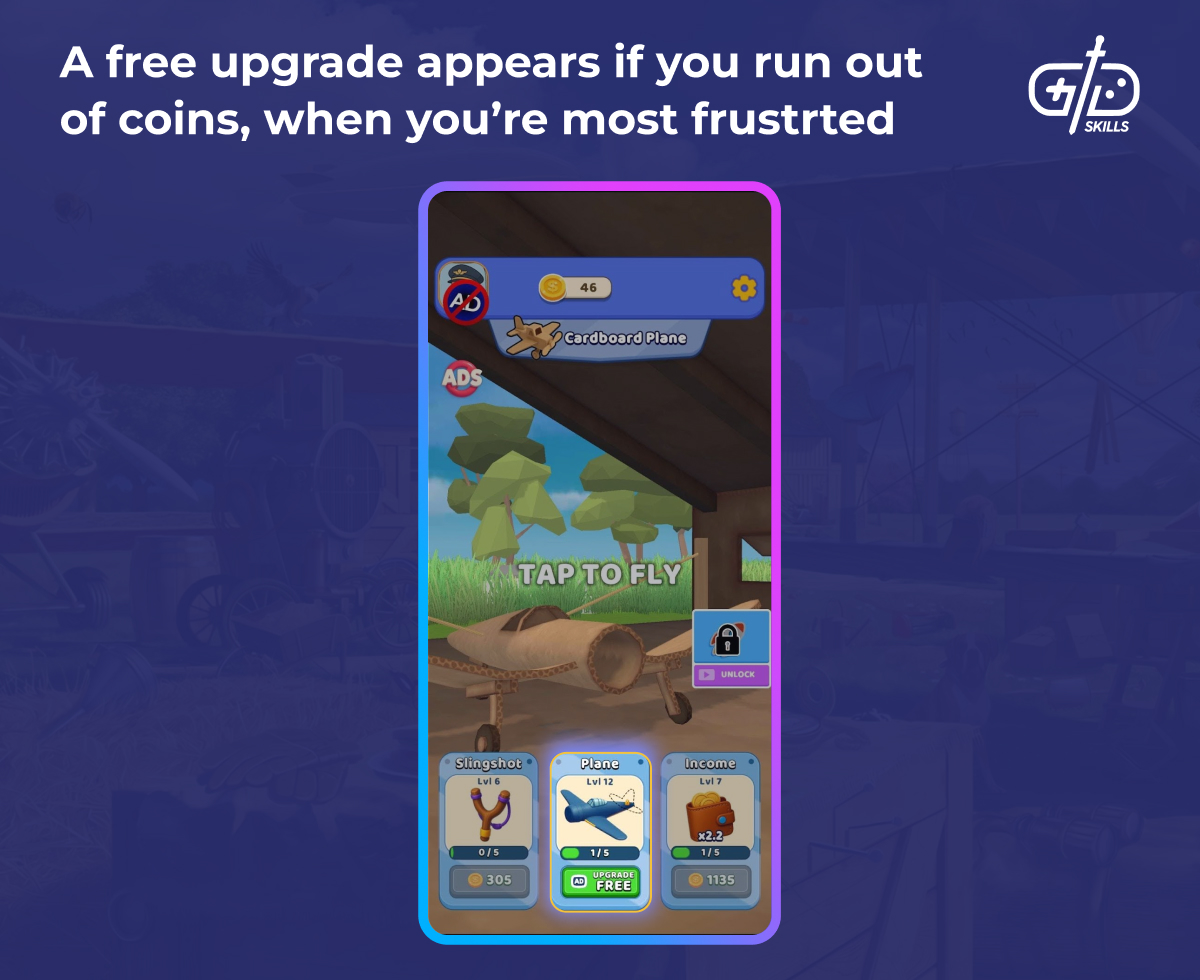

Monetization affects the types of mechanics that go into a game as well. Lives, in-game currency, and cosmetics encourage players to engage with systems that generate revenue. Players who enjoy the game for free watch ads to earn more lives and other valuable items. Players who invest their own money get an ad-free experience. Players generate revenue through play either way. Designers continue creating new items and encounters in levels to keep players engaged with the monetization systems of live service games.

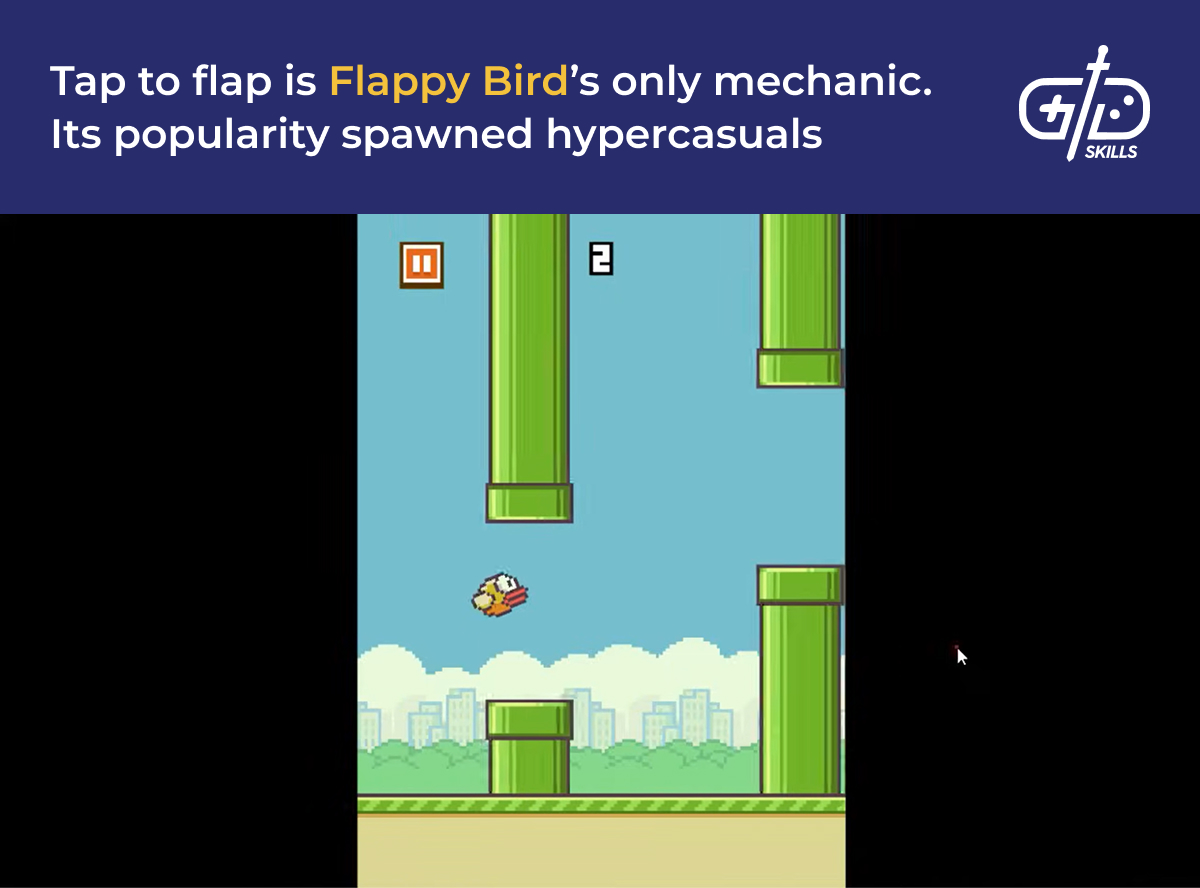

Hypercasual is a monetization strategy which has dominated the mobile market the past 10 years. Hypercasual games are easy to engage with one-handed and require zero experience to start playing. They earn money by showing rewarded ads to the player: rewards come in the form of extra lives, currency, or items. Not all single-mechanic games are hypercasual as a result: Beat Saber is a casual, single-mechanic rhythm game, but no-one considers it hypercasual.

The fundamentals of casual game design are rather simple because the category is so varied. Any genre, mechanic, or aesthetic experience imaginable is a viable casual game concept. The variety of options is part of what makes designing effective casual games challenging. Keeping the game simple enough for anyone to play but with enough depth to remain engaging is the core challenge in designing a casual experience.

What mechanics are used in casual game design?

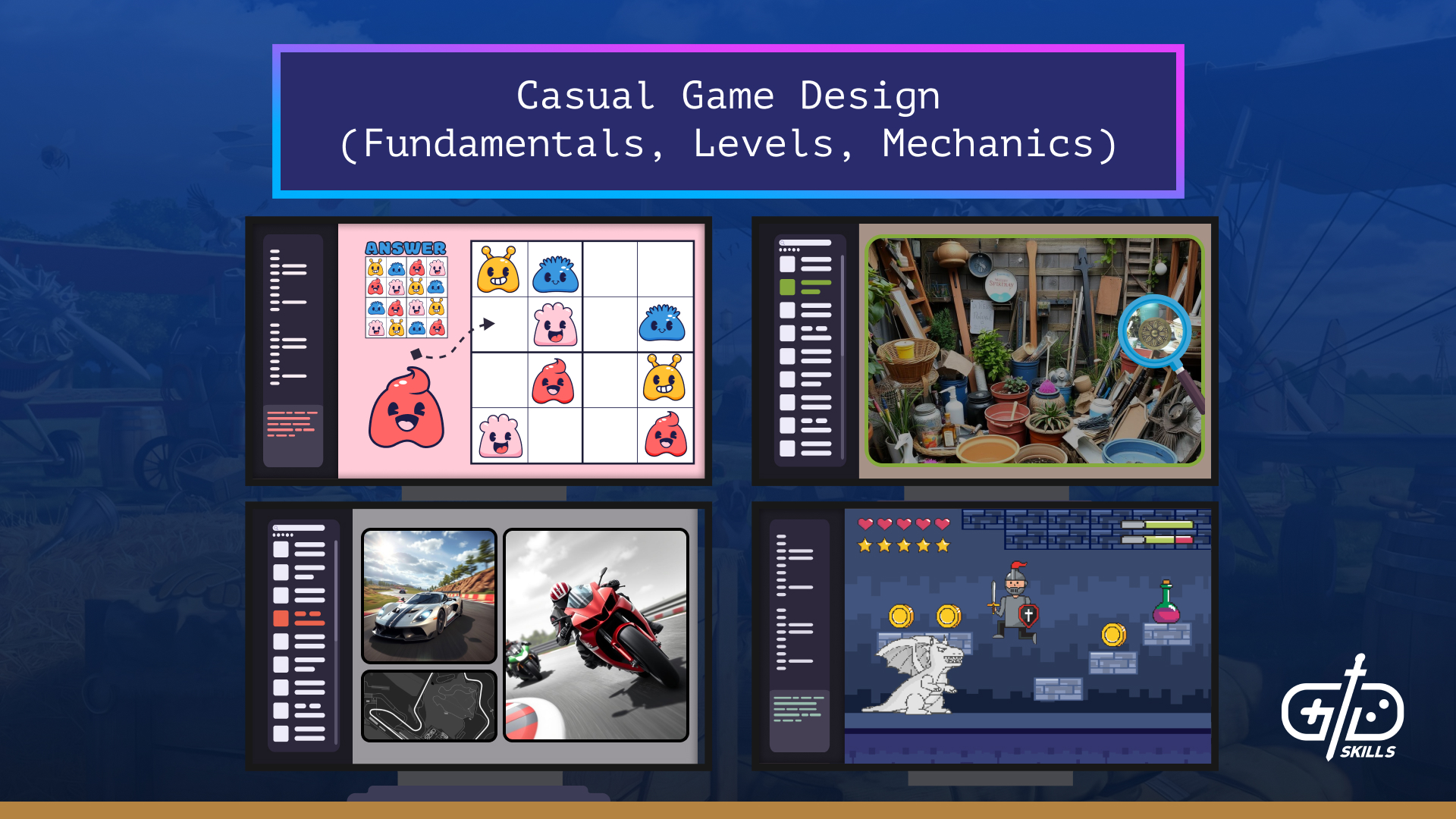

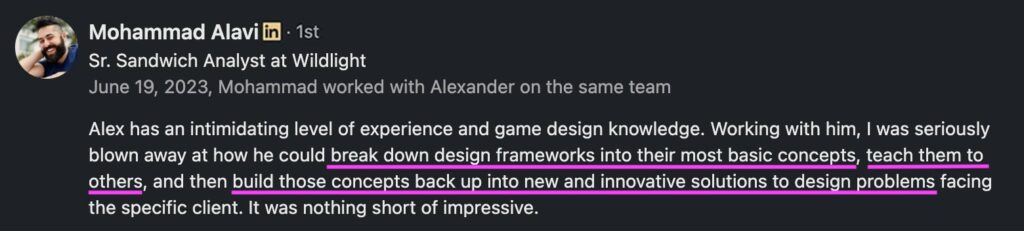

Mechanics used in casual game design are include matching puzzles, endless runners, searching games, and many others. The core mechanics are as simple and few as possible in each casual game. Casual games tend to start with an action audiences are already familiar with. Puzzle games are common in the casual space since they constrain the player to a few simple actions. While puzzle games are popular, all casual games benefit from considering how to motivate the player.

A casual game needs to be approachable for someone who hasn’t played games before. Think of the first time playing a console shooter and how difficult it is to control. Aiming with one stick and shooting with another isn’t intuitive to a non-gamer, and even still requires aim assist. Casual games avoid 3D movement, and when they do enter the third dimension, movement is simplified. Games like Mini Car Racing’s endless mode give clear buttons for movement: two arrows for switching lanes, and colliding with objects to interact with them.

Touchscreens provide clear inspiration for making intuitive mechanics. Sliding a finger back to launch a sling in Angry Birds feels correct. Fruit Ninja is another classic example where the player quickly learns the only thing they need to do: slice their finger over fruit that pops into view. Games also take advantage of the unique features of a mobile device to intrigue the player. The endless runner Lane Splitter uses the iPad tilt function, having players lean the tablet left and right to guide the player character around obstacles.

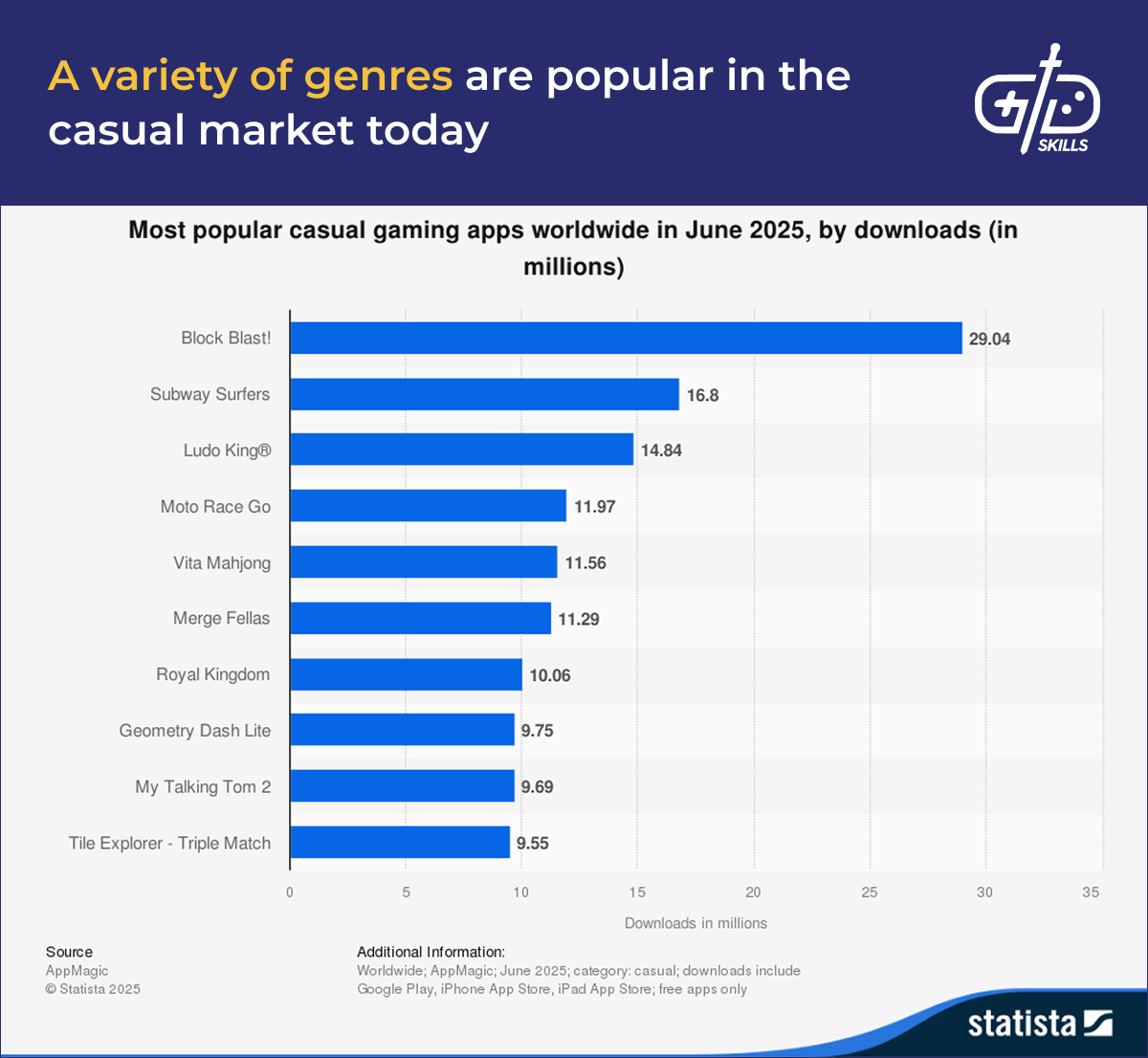

The most popular casual games of 2025 show how varied the mechanics are. Puzzle games, endless runners, classic board games, racing games, and simulators are represented in the top 10. Each variety represents a different core mechanic. The top puzzle games ask players to carefully place blocks to clear items: Merge Fellas and Block Blast fall into this category. Matching games like Mahjong and Royal kingdom ask players to pay attention to a field of information, deciding the best move to clear the board. Endless runners of several types remain popular: Subway Surfers, Moto Race Go, and Geometry Dash Lite players dodge, jump, and leap over obstacles.

Casual games overlay the mechanics with a simple meta system to keep players engaged. As Gregory Trefry says, there’s a liminal moment where play becomes a game. Stacking blocks is only fun for a minute or two. Stacking blocks with a goal (e.g., creating the tallest tower you can) suddenly becomes an engaging game. The creators of Diner Dash said it only became fun after they added a scoring system, which rewards players for chaining actions. The game was predictable before, since there was one best way to play, but with a scoring system, there are choices: play the game as fast as possible, or chain actions for a higher score.

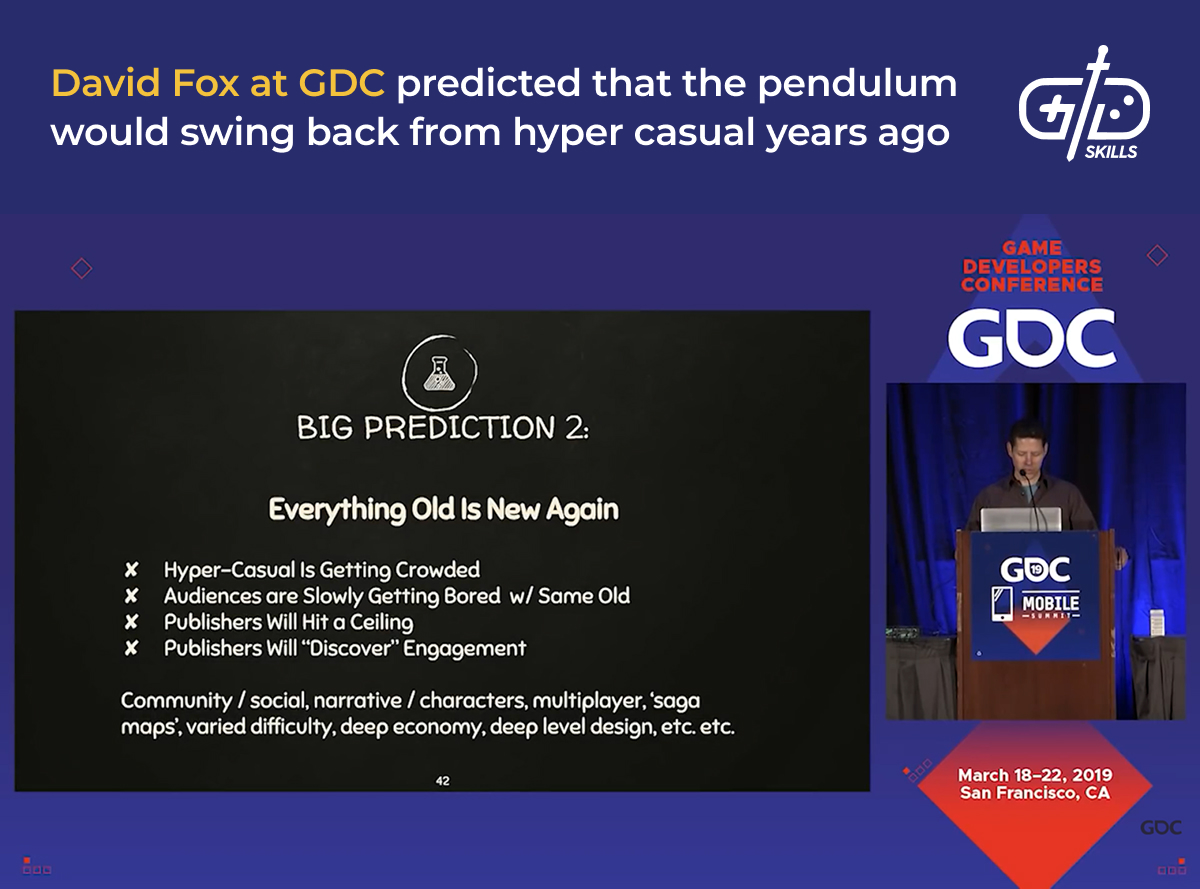

The types of mechanics that appear in casual games have changed as the market has changed. Big Fish Games and Popcap have been releasing paid PC and web games for casual audiences for over 20 years. The iPad and iPhone allowed touch mechanics to be used, so tilting, tapping, and swiping changed the ways players interacted with games: Fruit Ninja and Lane Splitter were early examples. The most recent era of hypercasual design with rewarded ad monetization began with Flappy Bird (2013), since which point F2P games have dominated the market.

How to design levels for a casual game?

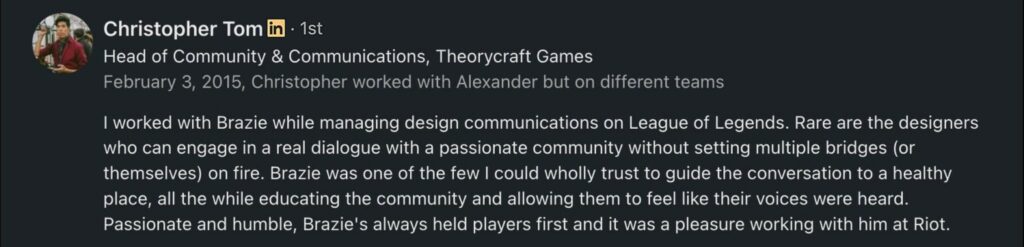

Design levels for a casual game that deliver a satisfying difficulty curve without alienating players. A level refers to a broad set of encounters in the casual games market. At its simplest, a level is a set of obstacles or challenges. The two major categories of level are endless levels and levels that come in stages. Each challenges the player in different ways, but the general principles remain the same in both. Levels and encounters give the player enough variety to stay engaged.

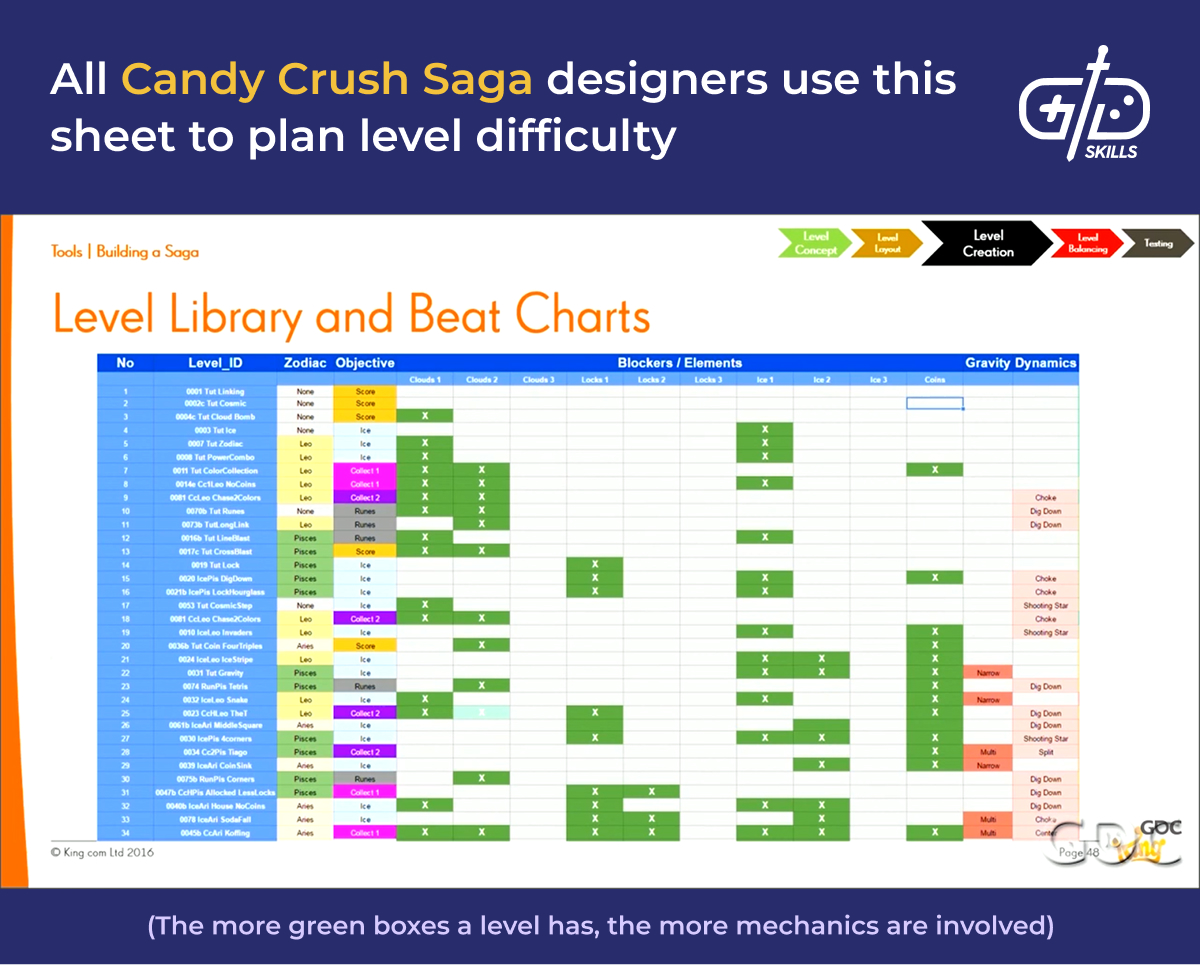

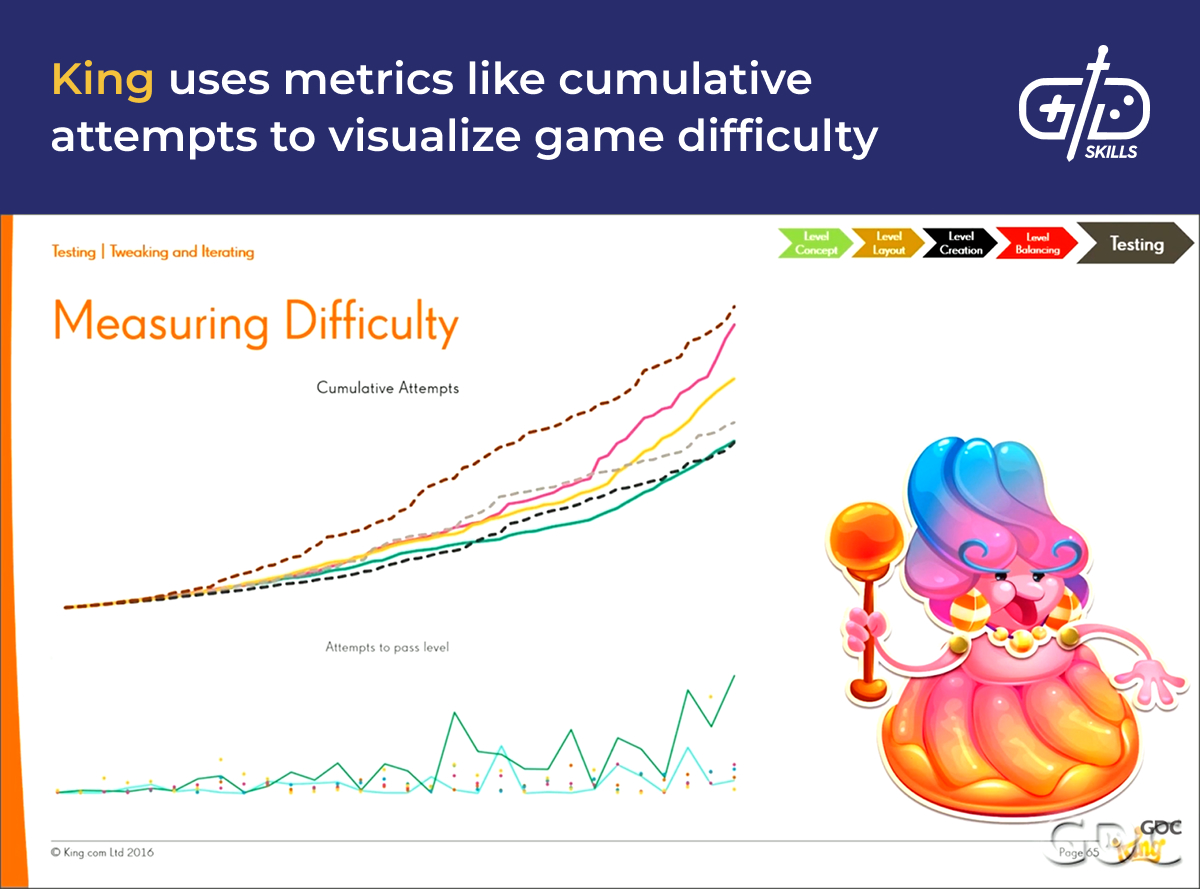

Difficulty curves ensure a consistent back and forth from easy to hard levels. Lower skilled players don’t want to get stuck, and higher skilled players don’t want to be bored. Even experienced players want to lose every now and then, or the game becomes a predictable exercise. Jeremy Kang, in his 2016 talk, suggests mapping out the difficulty of different levels in a sequence, when the game is in discrete stages. Designers easily visualize how difficult each level is with a color-coded spreadsheet.

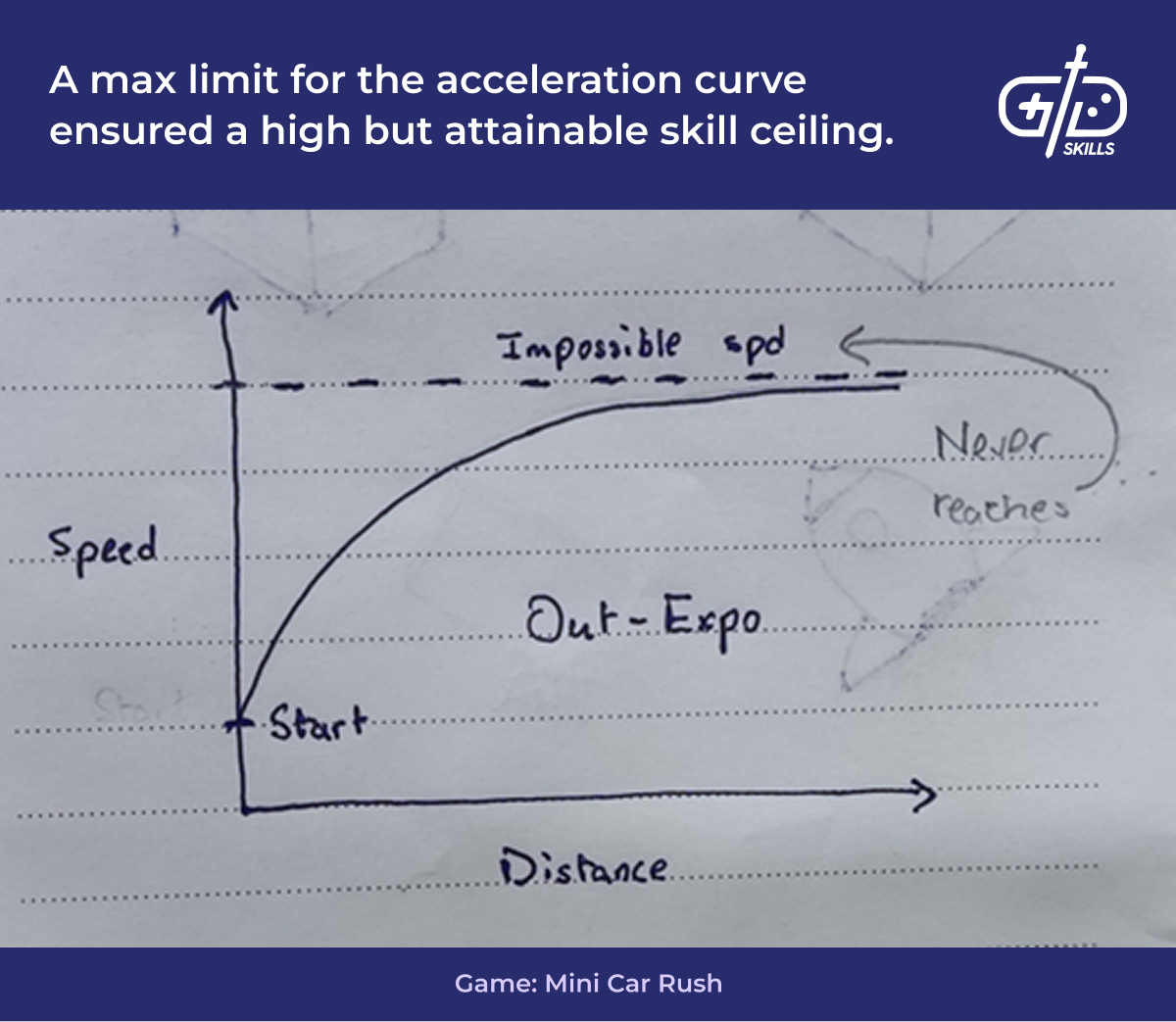

The continuous stream of encounters in endless games means difficulty works slightly differently than in games with discrete stages.The principles are similar in that the designer aims at a satisfying difficulty curve for the player. One way Mini Car Rush varies difficulty is by consistently increasing the speed along the track. A speed cap toward which the car approaches ensures the difficulty continues to go up while avoiding a situation like Tetris, where pieces begin to go faster than is humanly feasible to track.

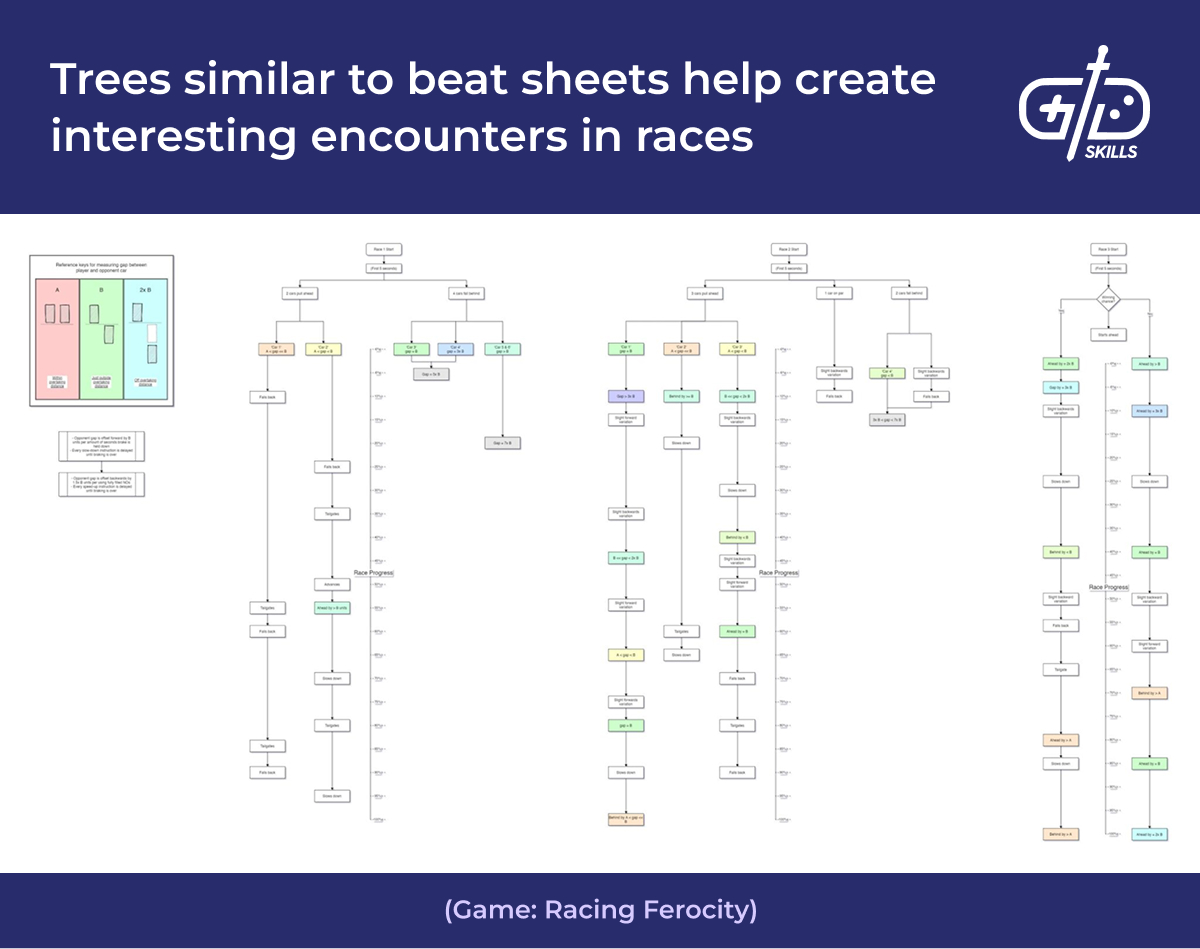

A consistently increasing difficulty curve is predictable, and variation is necessary to create an engaging experience. The AI racing mode in Racing Ferocity add a fresh challenge to the endless path. The difficulty curve creates moments of tension, where the player sometimes falls behind, sometimes pulls ahead, and other times get a surprise boost. The player alternates between safety and panic as the race continues. This is difficult to achieve without advance planning. I designed beats for racers so they remain a threat to players of all skill levels.

The business side of casual gaming asks designers to avoid instigating a game over outside of the main losing condition. Losing always causes player churn, and the goal is to minimize churn as much as possible. Create a variety of obstacles but limit the ones that result in a game over. The same principle applies to encounters like the Killer Cop in Racing Ferocity, where the player gets busted if they slow down enough. Busted players pay a fine, but they’re able to keep playing.

Casual games introduce new mechanics one at a time to avoid overwhelming players. Candy Crush Saga starts with one core mechanic: matching the correct color of candy. The game only begins to add further complications one at a time: candy that disappears when matches are made next to it, candy that clears rows when swapped, and powerful boosts players have the option to apply to difficult levels.

The reputation of casual games is that they hold the player’s hand through every process. Excessive handholding bores players. Having only one choice takes away the danger of losing and risks players getting tired of the game before experiencing what it is. Bejeweled is an example of a casual game that gets play started immediately. The only moves a player’s able to make are successful matches. The game ends when no possible matches are left, so whether new matches are possible is clear.

I worked to ensure new abilities were introduced clearly in Mini Car Rush as well. Players swipe down to duck under obstacles in a way similar to Subway Surfers. Mini Car Rush however has a shockwave ability, which is activated by ducking in midair. The game teaches the mechanic in gameplay. It forces players into a scenario where they have to duck coming off a train, discovering the shockwave ability organically. The accompanying ghost shows players an example of the action and further reinforces the lesson without pausing the game.

Hooks determine the direction of new levels and add variety to the level offerings. Jeremy Kang at King discusses his process in detail at GDC 2016. A twist on the gameplay itself is one type of hook: reversed gravity, new rules, a new enemy. Hooks don’t have to involve fresh mechanics, however, but some are as simple as new backgrounds or art styles. Mini Car Rush switches environments frequently to keep players interested in the endless gameplay.

Keep track of what players were interacting with when they quit to identify problem points. If many players lose to a specific obstacle and then quit the game, maybe it’s time to reconsider that obstacle. Removing the obstacle is in some cases the best option. In others, changing the obstacle to punish the player in a different way is the answer. The cop chase in Racing Ferocity takes away player coins rather than attacking them, providing a challenge while avoiding a game over.

Rigorous data collection and playtesting show whether the tutorials and difficulty progression are working as intended. King is a notable case study. King noticed player activity hit a wall at level 65 in Candy Crush Saga. The level was originally the last level, so the designers only identified it as a problem after expanding the game. The designers reduced the layers of frosting and removed chocolates until player metrics showed the average player was able to continue past the level.

Data collection applies to all aspects of designing an engaging experience, not just difficulty. Data showed players in Mini Car Rush were quitting the game before reaching the first environment change. The team didn’t want players to think the first environment is all the game is. The team tweaked the timing so that the first environment shift occurred before this point, catching the player’s interest before they began to get tired of the game.

How to design a character for a casual game?

Design a character for a casual game that orients the player in the game world. Character-based storytelling increases engagement, whether through humor, curiosity, or simply telling players why they’re doing what they’re doing. Characters however aren’t a priority in the casual game market. Casual games are smaller experiences, and quick turnaround means other systems and mechanics are more important.

Characters follow archetypes to tell a story in the short period of time a casual game lasts. The player begins the game by committing a hit and run. The protagonist’s car begins speeding away along the endless track to escape the consequences of the accident. The antagonist chasing the player gives them a reason to escape, a goal for driving through the environment. The characters are immediately understandable, fitting clear archetypes in the player’s head.

Characters in a casual game serve an indirect purpose: distinguishing a game from other games. Larger casual games companies sometimes copy successful work from smaller developers, and infringement is difficult to prove in court when game mechanics are at issue. Court is expensive, and even a solid case against the guilty party is hard for a small, mobile game development team to finance. The more solid the case, the more distinct the game, the less incentive the larger company has to take a risk on copying the game.

How to design UI for a casual game?

Design UI for a casual game that communicates information as minimally as possible. Casual games are simple, so players interact with a few mechanics at a time regardless. What game UI is present adds to the reward of playing the game or communicates important information about the game economy.

The game itself communicates much of the game state with its visual design alone. A player of Mahjong, Chess, Checkers, and Monopoly knows the game state by seeing where pieces are placed on the board. The controls are also simple for these games. Players tap and drag pieces to move them around, natural actions they’d use playing the physical game.

UI is a major visual component of the game, and a bright interface creates opportunities to reward the player. Much like the flashing lights of a slot machine, which transform pulling a lever into an addictive passtime, the visual impact of the game has its part to play in motivating players. Cookies falling in increasingly dense streams in Cookie Clicker, the “Sugar Rush!” message flashing at the end of a Candy Crush level, and the triumphant fireworks of Peggle signal that the player has accomplished something big.

What are the key elements of hypercasual game design?

The key elements of hypercasual game design are simple, one-mechanic games that draw in players long enough to make a return on investment through ad revenue. The model has remained profitable since 2015, although the market is starting to shift. Top publishers such as Rollic have shifted the focus to IAP over ads, resulting in a new variety of game taking on the new moniker “hybrid casual”.

Hypercasual games have a simple gameplay loop. The game is playable with the phone in one hand, and simple motions of the thumb are enough to progress. The simplicity means anyone is able to pick up and play. Flappy Bird is the classic hypercasual game. Designed in three days, the game has a simple loop of tapping to make a bird hop over obstacles. The game launched an industry of simple games using ads to profit off their growing popularity.

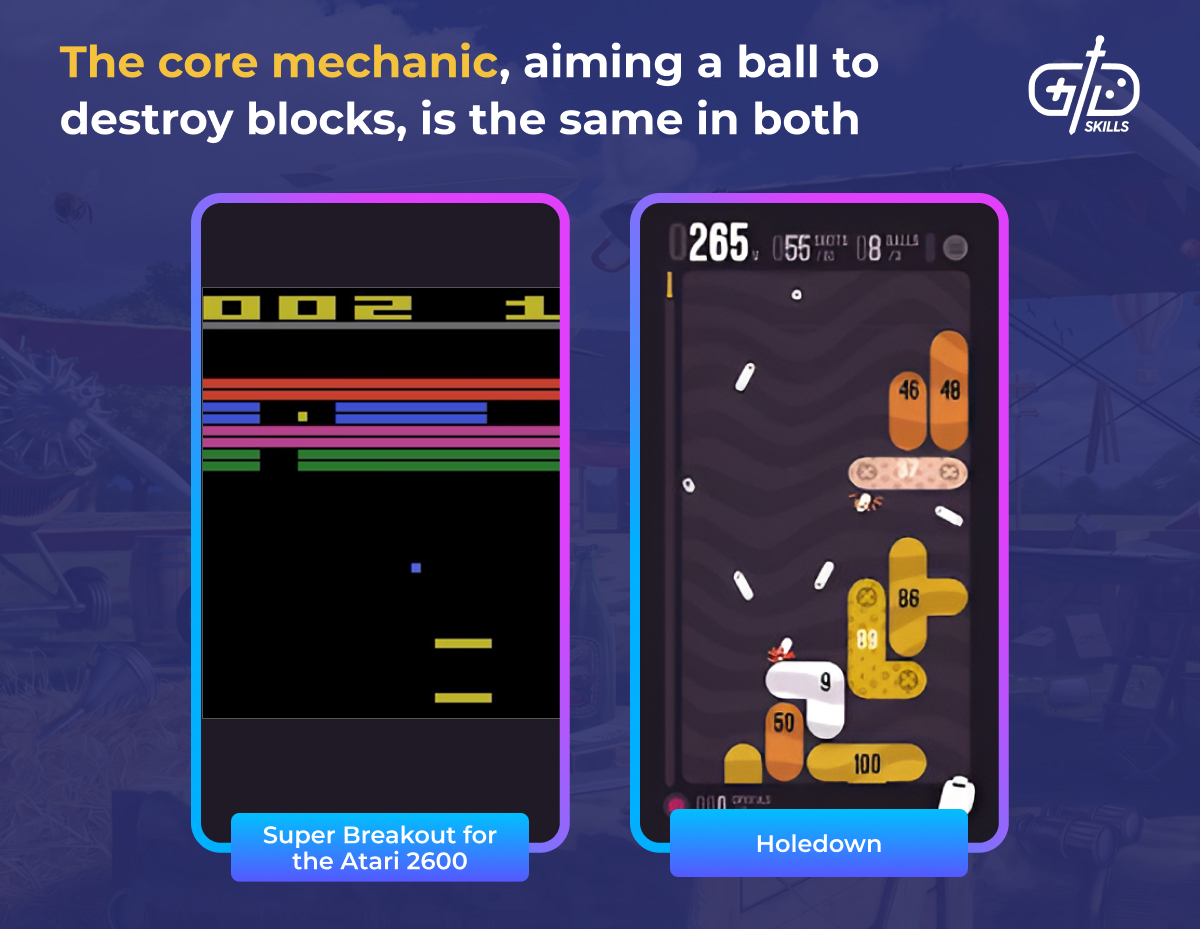

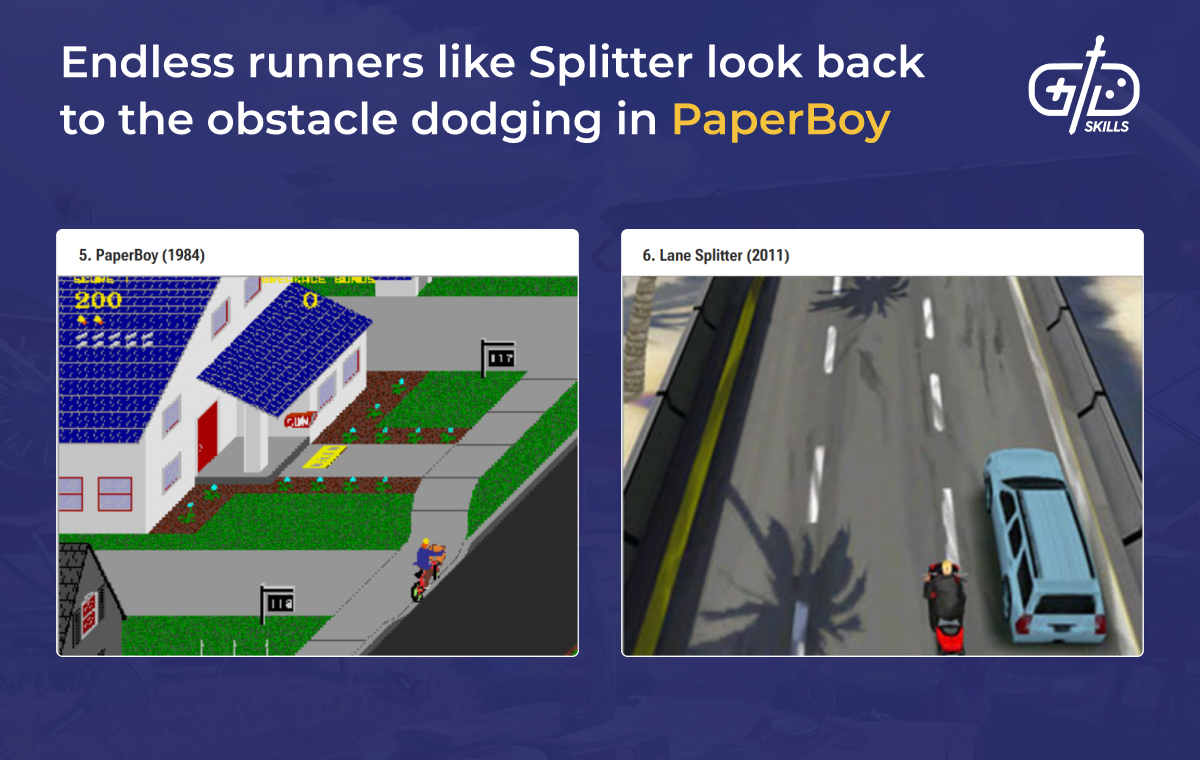

Hypercasual games often borrow gameplay loops from classic arcade games. Arcade games have simple controls because of the simpler technology and need to attract a playerbase of non-gamers. People are also already familiar with the premise of many classic games (Pong, Tetris, Breakout), which makes understanding a hypercasual game based on those mechanics even easier.

Hypercasual games by definition encourage players to engage with ads during gameplay. The standard model is that a meter drains until a failure state is reached: players have the option to watch an ad, or end the level there. Bricks and Balls Breaker, for example, gives ads to pay for more balls or powerups in case the player runs out of moves. Not all hypercasual games have a failure state, but stick to a variety of rewarded ads, ads between levels, and banner ads. Epic Plane Evolution by Voodoo, the biggest creator of hypercasual games, is an example of the latter model.

Hybrid casual, a type of mid-core game, is a fuzzy term used by players to describe games with similar gameplay to hypercasuals but fewer ads. Mid-core games rely on IAP and sometimes rewarded ads instead, avoiding banner ads or interstitial ads (ads which pop up between levels).

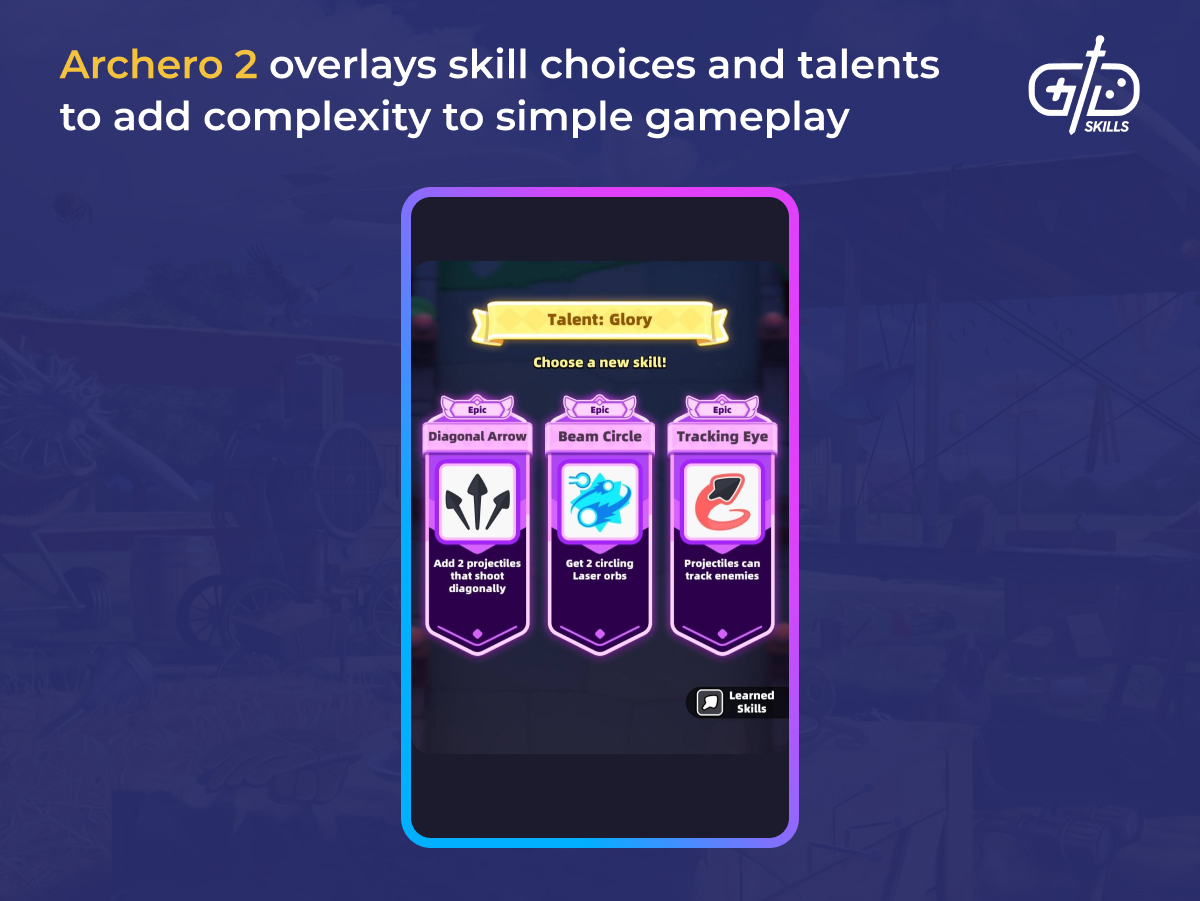

Archero is an example of a hybrid-casual game. The gameplay is simple, with movement being the only mechanic. The character locks on and attacks when standing still, and they stop attacking when moving. Enemy types with different abilities and a talent selection system add enough complexity to the gameplay to keep players interested longer term.

Hypercasual is a term for a monetization strategy, not a genre. Publishers know the core gameplay loop only keeps players engaged for a few days or weeks. Understanding key performance indicators (player retention rates, click through rate on ads, install rate) is important for knowing whether a game will make more money per user than was spent attracting them with ads.

What books are recommended to study casual game design?

The Art of Game Design and other general game design books are recommended to study casual game design. Casual games borrow gameplay loops, progression systems, and principles from hardcore games, so popular guides on game design still have much to say to a casual game designer. I’ve only read one of these books personally, but read on to see examples of other books that have the potential to be helpful for creating casual games.

The Art of Game Design by Jesse Schell is a book I’ve read that I recommend for any game designer. The book gives theoretical frameworks and lenses for thinking about how to design a game. The lenses encourage designers to think from the perspective of players, since they’re the ones who’ll pay money to play the game. Schell’s work isn’t a step-by-step process for making a game, but several ways to approach the problems of game design. Not every piece of advice is helpful for every designer, but every designer is able to find something helpful in it.

I’ve seen many other books on game design recommended online. I’m not able to recommend them personally, but consider looking into this list of new and popular titles and save some time on research. One attendee of the hypercasual games roundtable at the 2024 HIT conference recommended Advanced Game Design by Michael Sellers, a general game design book. The book seems to be more dense than Schell’s approach, but takes a holistic view that’s valuable for some newcomers to the field.

Experienced designers in the F2P space have published books on the subject in the past few years. Sergei Vasiuk and Vlad Dubrovskyi of Wargaming published a book on delivering live service games titled Running a Successful Live Service Game: Live Outside of Game Updates. Wargaming has supported World of Tanks, among other live service projects, for 15 years.

Stanislav Stanković of Supercell and EA created a similar guide titled Game Design for Free-to-Play Live Service. The latter book is very relevant for the mobile and casual market specifically, for which only a few dedicated books exist.

Books on casual game design are uncommon. Casual Game Design by Gregory Trefry is the most popular, but is from 2010. The hypercasual movement and monetization strategies go undocumented in the book as a result. Trefry, however, pulls general principles from the games he discusses. While the examples are old, what makes them fun hasn’t changed.

Where to find a casual game design template?

Find casual game design templates online. The principles of casual game design have remained consistent for the better part of half a century, so there are many games out there to look to for inspiration. The web also has numerous assets and project management tools for designing casual games.

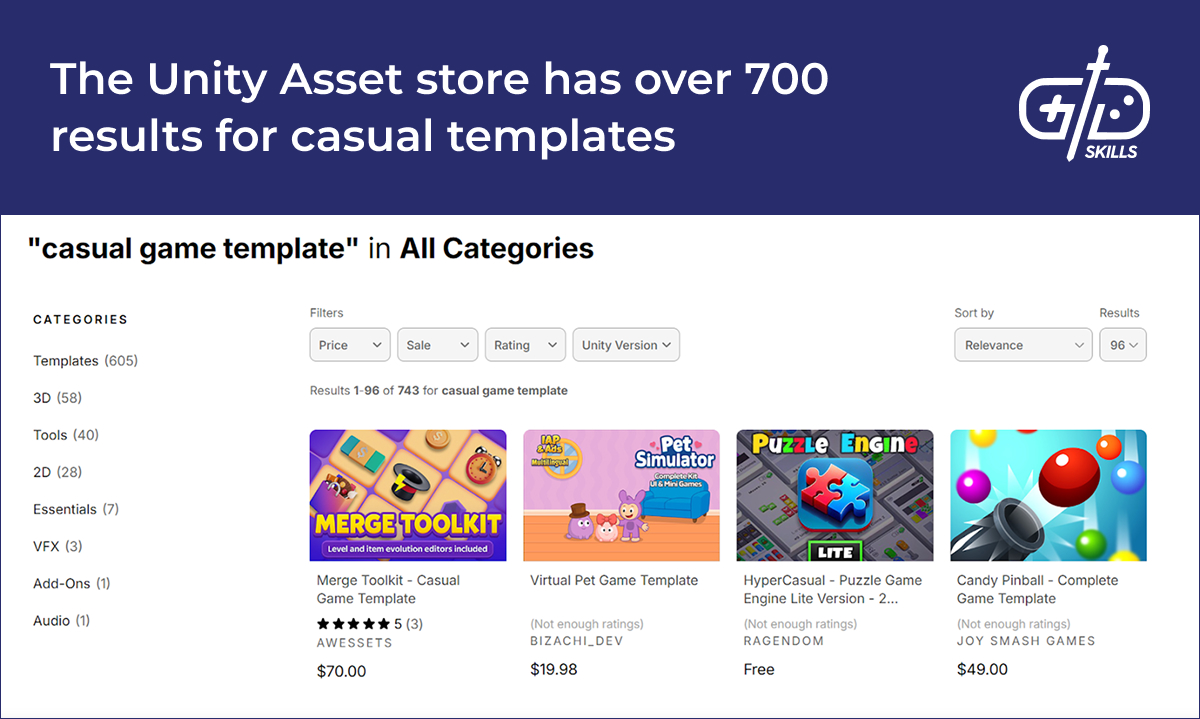

Assets for casual games are readily available online. The Unity Asset Store has mobile-ready GUI and audio assets. The asset store also has genre-specific templates: platformers and match 3 puzzle games are the most common. Hypercasual games don’t require templates and premade assets at all since they’re quick to make from scratch. Think of how Flappy Bird was made by a beginner game programmer in a few days.

Find an addictive core gameplay loop that sets the game apart. A common place to start is to look to other games for inspiration. Older arcade titles followed the principles of casual game design because they existed in a context where gaming itself was novel. The classic Frogger gameplay and premise inspired the hypercasual hit Crossy Road. The endless obstacles, variations between land and water, and one-mechanic gameplay lent itself well to the hypercasual model.

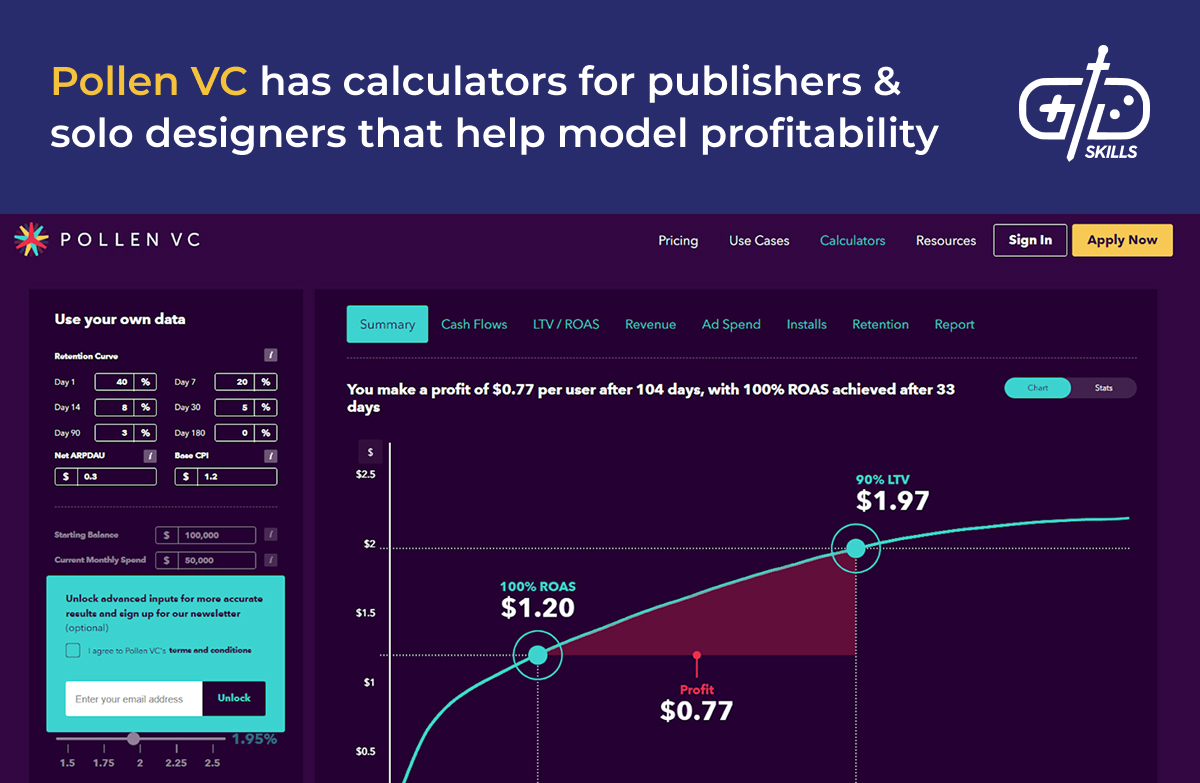

Calculators for KPIs are an important resource for getting into the business side of F2P game design. KPIs are key performance indicators, which tell a company how viable a game is. A calculator needs a few KPIs: player retention rate at certain benchmarks (1 day, 5 days, so on), the average daily revenue per user, and the cost per install. With this information, the software calculates how many days a game will take to become profitable, if at all. The results give developers important data for investment opportunities.

What is an example of a casual game design document?

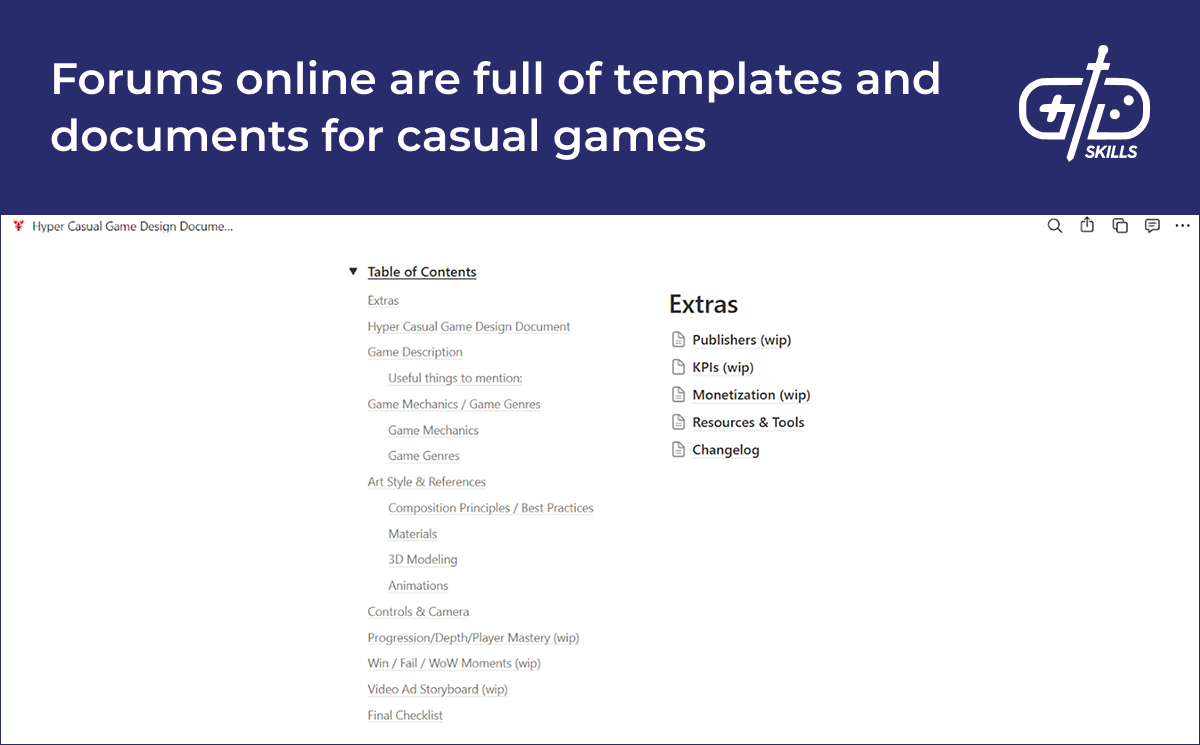

There isn’t an example of casual game design documents since the genre doesn’t need one. There are many types of casual games, and all have few mechanics, narrative elements, and game modes compared to hardcore games.Teams are also smaller, so detailed artwork details, narrative arcs, and level descriptions aren’t necessary.

A GDD is useful for a larger or expanding team. Documenting gameplay systems and mechanics is important for new designers to get acquainted with the existing content. Supporting the game with new levels after release requires a bible of rules, systems, and gameplay elements. The art, narrative, music, and levels don’t need such detailed documentation. Levels in casual games are based on a set of interactions between mechanics, not a narrative structure or exploration. Detailed descriptions of levels aren’t necessary.

A small team or an endless game might use other solutions than a GDD or in addition to a GDD. Visualizations for level beats, difficulty, and gameplay loops help with clarifying the vision. Mechanics and levels, however, change on the fly in response to playtesting and there usually aren’t many different designers working on a project regardless.

I created a wiki for Mini Car Rush as an extensible and suitable solution. The main purpose is to collaborate with teams, with just enough details to keep track of the full design. I drafted all the different components of the game in short, easy-to-read bullet points. Staying this concise meant that it was hard to comprehend the documentation by itself. However, with a workflow involving frequent feature brief meetings, the details made sense afterwards and kept the team aligned on the design.

Please tell us what your experience is with casual game design! What mechanics are used in casual game design? Do you have anything to add about casual game UI? Are you a level designer or live service content creator who has something to add? Please let us know in the comments!