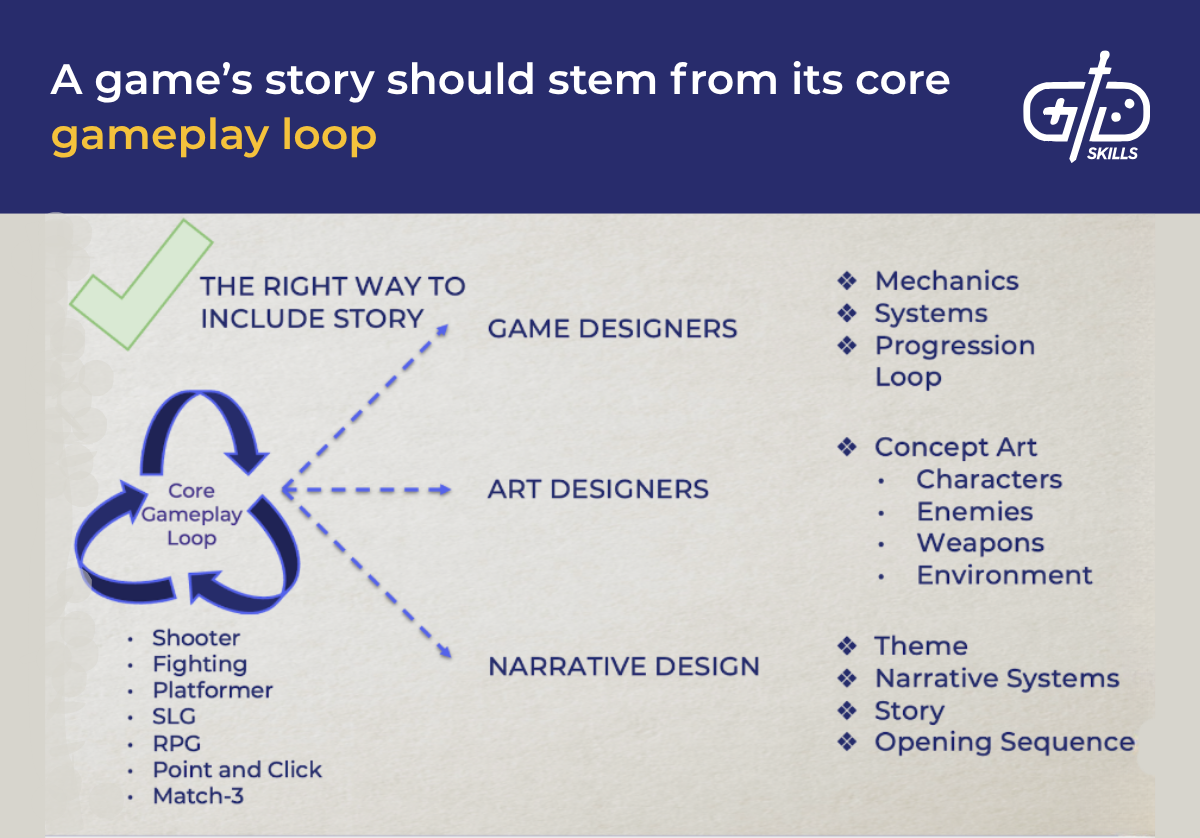

Write stories for video games by determining whether the project is primarily about gameplay or narrative. Games that are built around mechanics need writing that places gameplay in the most exciting locations and raises the stakes for player failure. Games that are narrative-heavy require writing to build a compelling world, interesting factions, and characters the player becomes emotionally invested in.

Writing for gameplay-based and narrative-based games differs slightly in focus, but the two share many similarities. Both styles of writing need protagonists, antagonists, obstacles, conflicts, and resolutions. Gameplay-based projects often need retro-fit style writing, where gameplay designers come up with an interesting scenario that the writers create a narrative reason for. When narrative is the focus of a project, the story elements are often created before the gameplay. Read on to learn about writing stories for video games and how it differs from other media.

How to write a story for a gameplay-based video game?

Write stories for a gameplay-based video game by creating reasons to show off the best of the gameplay experience in the most dramatic contexts. Story beats, lore, and explanations are built around gameplay set pieces in a gameplay-heavy experience. Instead of forcing the gameplay to fit the narrative, use narrative elements to increase the intensity and fun of the experience.

Give gameplay designers as much room as they need to create super-dramatic, max-engagement-style gameplay. There’s a reason Mario games take place on volcanoes, cliff edges, and rainbow tracks in outer space – and it’s not to frustrate the health and safety officials of the Mushroom Kingdom. Write reasons for the next stage of the adventure being fun and a thematic shift. This shift comes from a change in tone or gameplay mechanic focus. Don’t be afraid to deviate from the original plot outline if the gameplay designers need wiggle room.

1. Start by defining the mechanics

Start writing a gameplay-focused story by defining the game mechanics. Establish exactly what the player does, how often they do it, and what (if any) secondary or tertiary mechanics support the primary one. Designer Shigeru Miyamoto has stated that he always begins with gameplay and only thinks about story once the mechanics begin to feel fun and novel.

In the context of 1985’s Super Mario Bros., this looks like Mario (then “Super Jump Man”) having his signature floaty jump refined, with some enemies, obstacles, and challenges to contend with. Miyamoto has said he wanted players to feel like they were on a journey through a new world, instead of reading a book. A simple “save the princess from the evil monster” plot provided light plot motivation and a fun, plausible reason for the increasing challenge of each level.

2. Define a protagonist

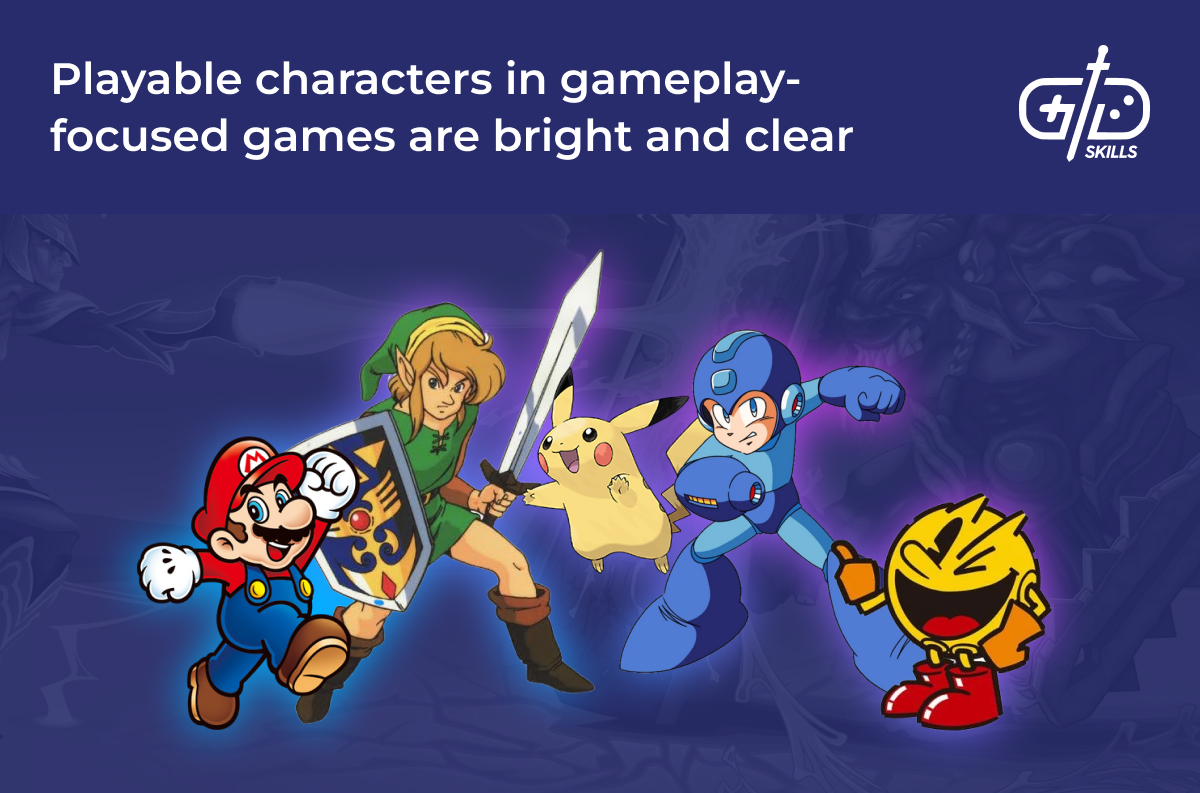

Define your protagonist to make sure your player embodies someone/something fun, exciting, and/or sympathetic. For action-heavy, gameplay-focused experiences, the main character doesn’t need Shakespearean moral complexity. A relatable, cute, or thrilling character archetype that’s easy to see onscreen is enough to get players interested. The main focus is on creating a character who has a compelling reason to do the main action over and over. These compelling reasons are often the remit of the writing team.

Start high-level when defining your protagonist. Think about story reasons as to why they’re adept at the main actions that constitute gameplay. Playable characters are variously magical creatures, genetically modified super soldiers, or anthropomorphic cyborgs. In a gameplay-focused experience, the writing works to justify mechanics. Don’t be afraid to think outside the box in pursuit of the ideal protagonist for the gameplay loop. Designs like Earthworm Jim, the Katamari Ball, and Octodad didn’t come from pale imitations of other games. They came from referring back to step one – focus on mechanics. Borrow from nature, comic books, and your dreams.

3. Plan the world environment

Plan the game’s world environment by outlining fun reasons for the action to take place in the most exciting, dramatic locations. The gameplay is the focus, so story explanations for environments don’t get put under the microscope in the same way as in more narratively coherent games. We accept the familiar – ice level, fire level, industrial level, urban level, etc. – in platformers with minimal explanation because those environments are fun to explore. The same logic applies to resource distribution in real-time strategy games (RTS) and action roleplaying games (ARPGs). Players understand that these items are required for crafting and other mechanics and accept loot drops that are more functional than thematically consistent.

Movement, exploration, and combat mechanics are the three primary ways players interact with gameplay-focused experiences. Running, jumping, wall-running, climbing, sliding, and swimming are only as fun as the medium they occur in. (Try swimming in a pool of bees.) Build the environment around the fun inherent in the movement mechanics. (Think using Mario’s floaty, controllable jump to land on moving platforms.) The same principle applies to combat and exploration. Plan environments that give players fun angles to attack and retreat from, with hidden ledges and areas to find.

4. Come up with a central conflict

Coming up with a central conflict requires writers to create a protagonist, an antagonist, and a point of conflict between them. Antagonists are vital to video games stories. Effective game villains believe in their cause, embody the conflict, and mirror the players’ journey, giving players something to defeat. There must be a resource, person, or point of principle with which your playable character has an intractable disagreement with that antagonist. The point of conflict doesn’t need complexity or moral grey areas like in a gameplay-heavy experience. Players just need a fun reason to dislike the baddie.

When the player is generally one mistake away from losing a life, the central conflict is secondary to the spike traps, bullets, bombs, or falling meteors. Bowser’s princess kidnapping antics don’t create a Frank Herbert-inspired plots within plots conflict. The backdrop of big lizard man’s got my princess is enough to keep Mario players pushing forward because the Mario series creates much of its moment-to-moment tension from the perilous gameplay.

5. Outline the plot

Outlining the plot for a gameplay-focused experience revolves around what actions the player takes and why they take them. If Mars is our setting, we have to determine the what and why of player action within the plot. In the context of a Mars-based RTS, the mechanics vary depending on whether the plot involves defending against invasion, resource collection and trading, or aggressive colonization. (Or a mix of all three.)

Create a draft with a timeline of events that must occur for the player to progress through the plot. These events are typically narrative payoffs and major story beats. Working with level and gameplay designers helps to place exciting challenges before major story beats and moments of quieter down time afterward. Gameplay-focused games with multiple layers to gameplay often introduce new mechanics alongside new acts or story beats.

6. Remember the plot is a device to showcase mechanics

Use the plot to serve the mechanics in experiences where the gameplay comes before the narrative. The plot isn’t the main appeal of Battlefield, Call of Duty, Mario, or Doom. In these kinds of experiences, the plot acts more like a delivery vehicle to justify maximum fun and support the pace. Doom (2016), for example, boils down to, “Demons invaded – get them before they get you.” It’s enough to drive the escalation in combat encounters as the player progresses.

Stories thrive on drama and tension. The overarching plot covers the broader drama of what’s ultimately at stake, but writers look for story reasons to make gameplay more engaging in the moment. Simple plot devices increase tension. Bombs on timers, self-destruct mechanisms, rising water levels, and a plague of nanobot locusts all use deliberate time challenges or increasing difficulty levels to accentuate plot points and vary the pace. The plot must be in thematic harmony with a game’s mechanics. If the mechanics emphasize tight control, write locations with confined spaces and many options for interaction. If the mechanics emphasize freedom, write for larger spaces with a broader distribution of interactivity.

7. Research other games and movies

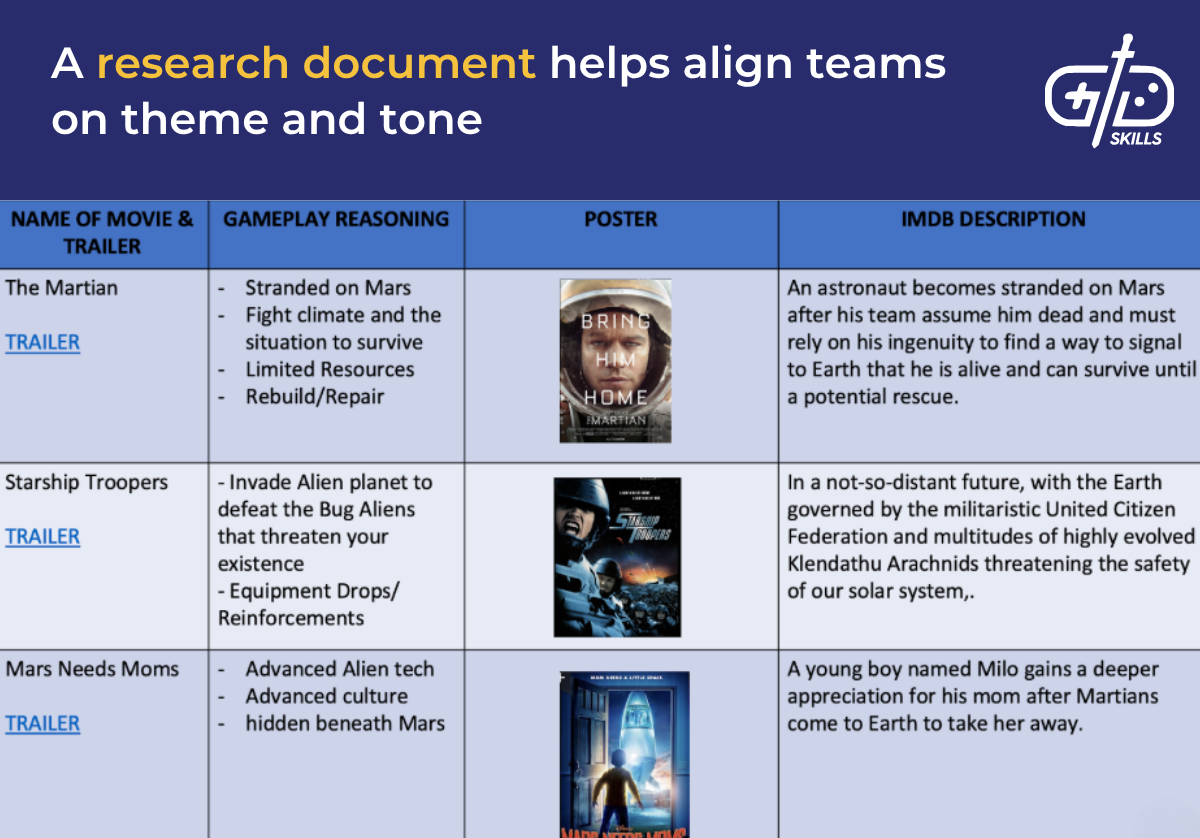

Researching other games, movies, comic books, TV shows and other media helps to give a development team a common frame of reference. Art styles, depictions of technology, gameplay mechanics, color palettes, weapons, and architecture are easier to understand through references. Build a bank of material that transmits ideas of theme, tone, and story without directly copying unique elements of other people’s IP.

Create a document to share with the rest of the team when researching games, films, and other media. A dry list of film, book, and game names doesn’t spark much imagination, so explain why each piece of media is included and link to its trailer, a poster image, and the logline from the back of the box on IMDB. Go into specific detail about why you included it – gameplay, art reference, tone, or theme.

How to write a story for a narrative-based video game?

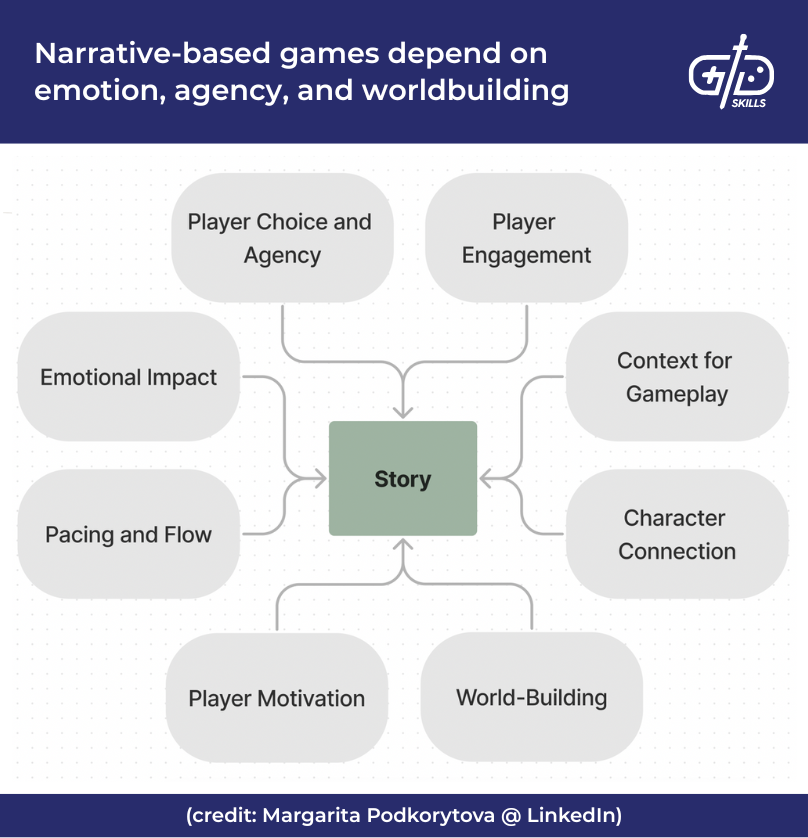

Write a story for a narrative-based video game by focusing on the timeless elements that draw humans into narrative media: compelling worldbuilding, fiery conflict, and interesting characters and plot. Genre expectations and mechanics also play a role, as most narrative-based worlds are full of discoverable lore and interactive storytelling elements. Other media demand that writers create stories that viewers/readers/listeners experience as a third party. Writers of narrative games are designing a world and characters to be experienced firsthand.

Story, characters and worldbuilding bear more of the burden of entertainment in narrative-based games. Gameplay is still a non-negotiable element of the medium but the interaction in story games doesn’t need to be as visceral or arcadey as in gameplay-heavy experiences. Interactive Fiction (IF) is perhaps the most mechanics-light of any game genre, depending heavily on worldbuilding, character interaction, and plot while offering simple choice-based interactivity. The physical timing and skill of arcade games is entirely absent, but the level of choice and consequence keeps players engaged.

1. Define the world

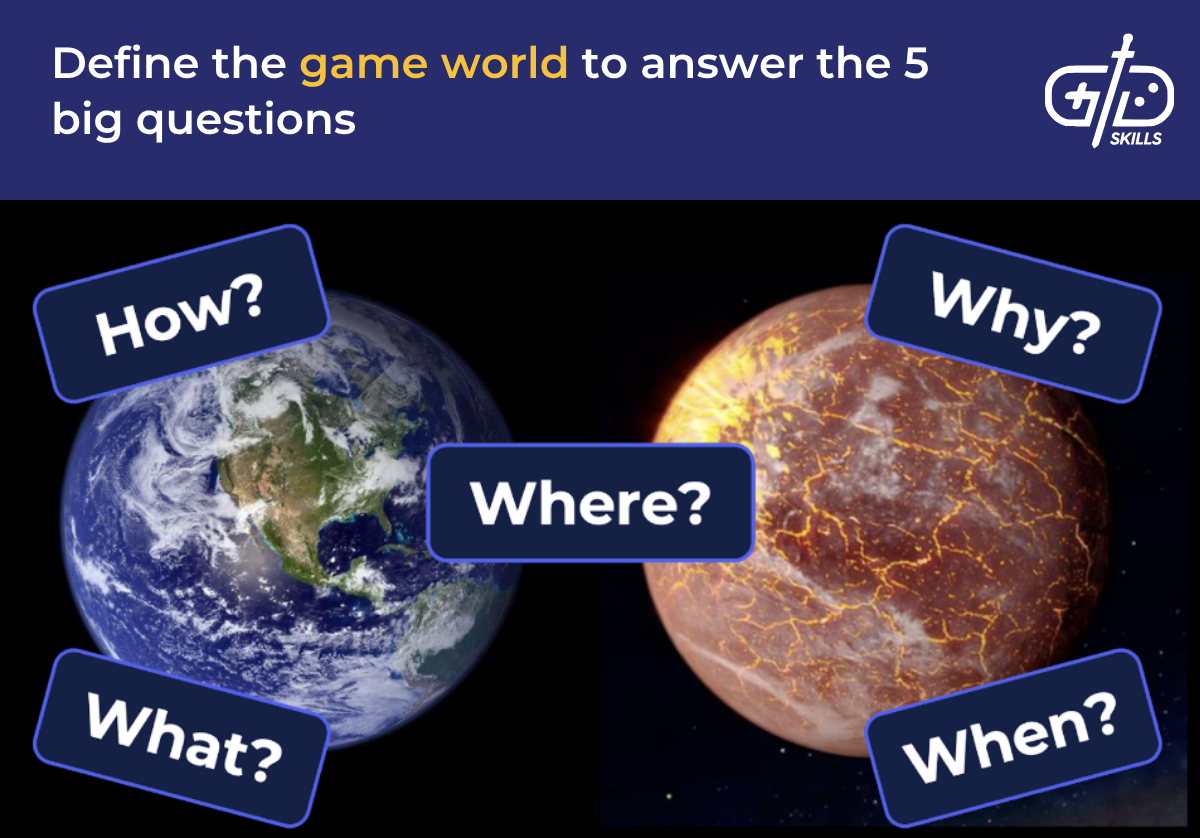

Define the world early in development so that the game world doesn’t exist solely to facilitate gameplay, but also to draw the player deeper into the fantasy. Effective worldbuilding makes players feel the universe exists outside of their own interactions with it – like the real world. Games like Mass Effect and Dragon Age hint at historical events, unseen factions, and far off places without lore-dumping walls of text. (Those are available in the codex, too.)

Resources, factions, continents, and nations help you create conflict on a macro scale. Determine where the game is going to take place – Earth, another world, the future, or a combination of elements. Consider how the place was formed, what resources exist, and who controls them. The factions, nations, cities, and citizens of the world are all influenced by these high-level decisions about worldbuilding. And the factions, nations, cities, and citizens are what give us the next component of the story: conflict.

2. Define the major source of conflict

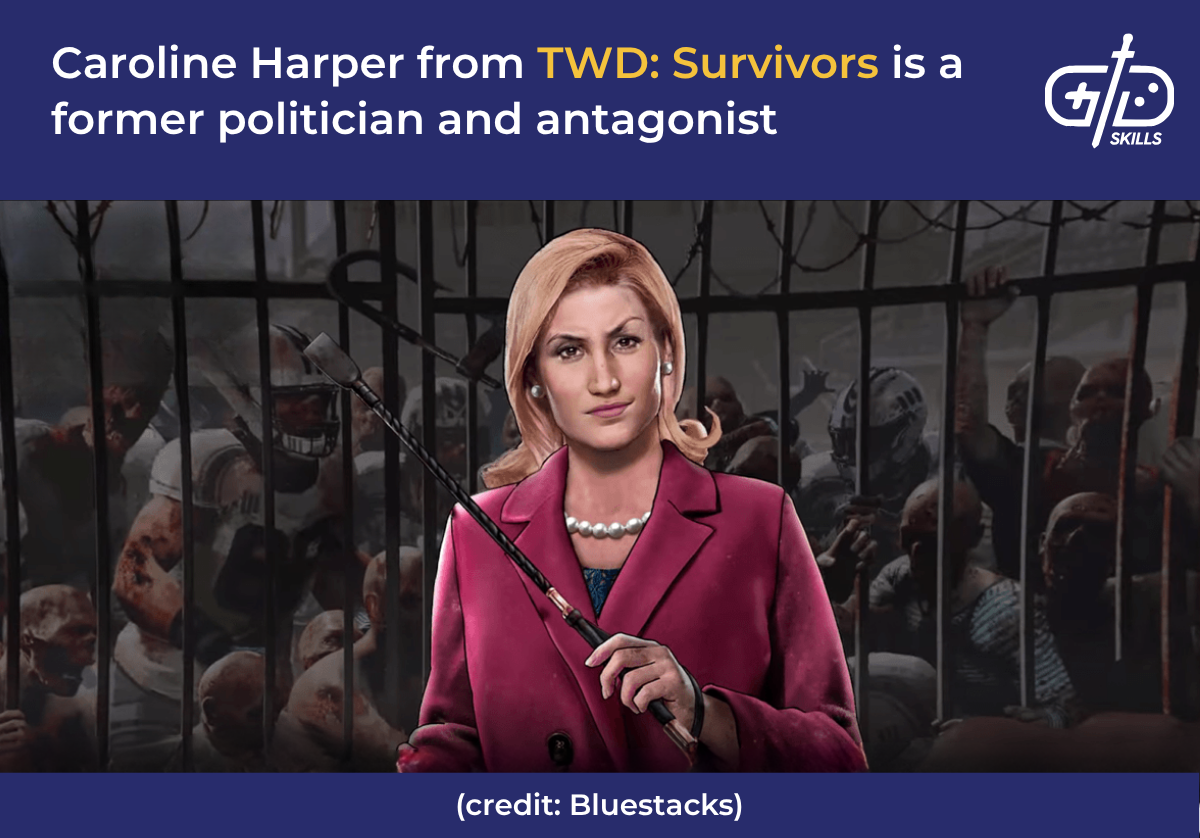

Define the major source of the conflict to increase the satisfaction of overcoming the gameplay challenge. The players’ level of satisfaction is linked to how invested they are in the central conflict. The major source of the conflict must offer a compelling reason to play that holds up from a storytelling perspective and not simply as a backdrop to the action. Heavily gameplay-focused experiences get away with simple, archetypal conflicts. Narrative games demand more thought-out conflicts and resolution options. The Walking Dead’s relatively open-ended worldbuilding allowed me to get creative when designing villains and conflicts.

Determine what the main conflict is over by asking why the various hostile factions are fighting. Resource wars, ideological difference, personal disagreement, or generational warfare – the scope is limitless. Real conflict doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Ground the game’s struggles by placing them on a historical timeline with a coherent world history that leads up to this point. A historical perspective gives your protagonists, antagonists, factions, and NPCs believable reasons for their loyalties, enmities, and biases.

3. Create characters which embody the conflict

Create living embodiments of the central conflict to drive the theme home and connect the characters’ arcs to the plot. Games are not moody, mid-20th century French novels. Don’t be afraid to exaggerate and caricature to get the idea across, depending on the style and tone of the game. Halo’s Master Chief isn’t a nuanced, morally complex character, nor is he particularly charming or funny. Master Chief is, however, a powerful-feeling, understated, blank slate marine archetype that’s easy for the players to project themselves onto, deepening the power fantasy at the heart of the game’s appeal.

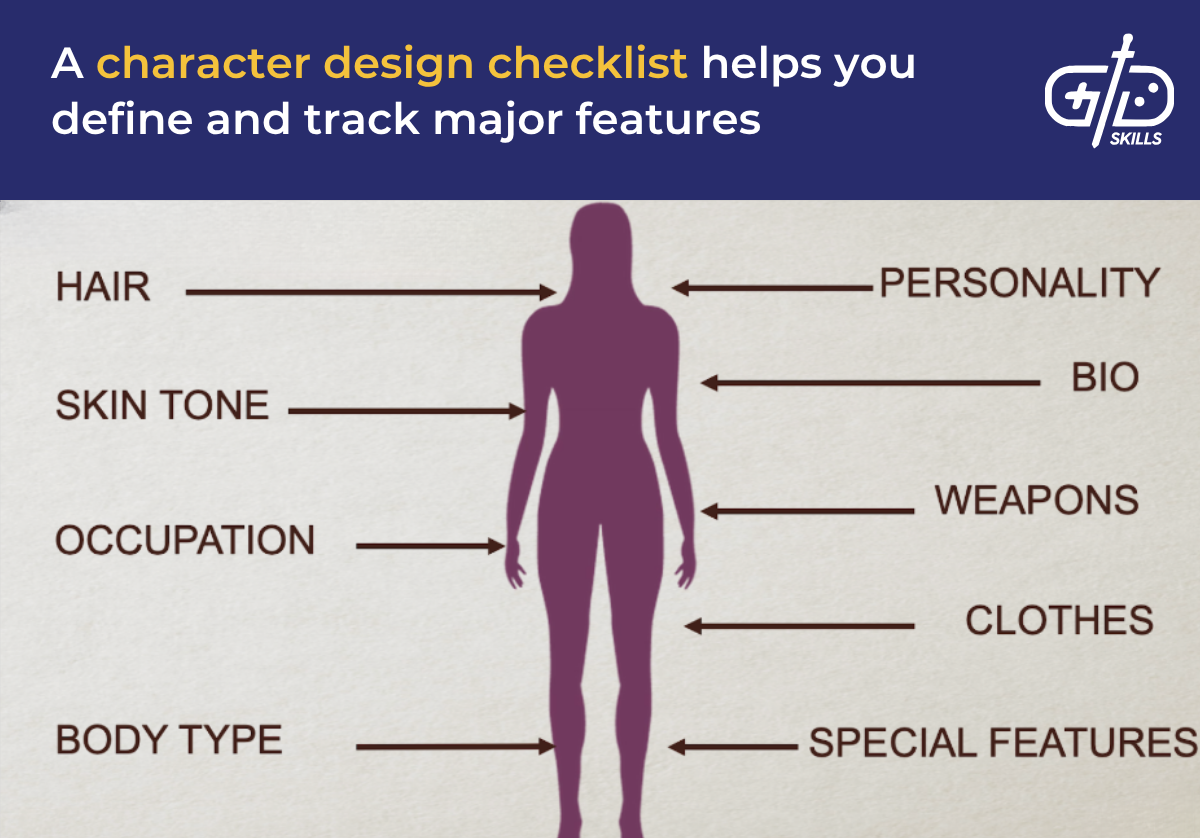

Every project is different, but using a character design sheet like the one above helps designers line up the most important elements. Focusing on what the character represents visually and is capable of mechanically helps designers to create living embodiments of the game’s central conflict. When the plot revolves around a foreign authoritarian power clamping down on indigenous magic, create an unabashed native mage who looks and acts in direct opposition to the fiction’s “evil” faction. The primary antagonist must embody the opposite side of the same conflict, presenting cold clinical rationality in opposition to the nativist, magical heroes, for example. (Or, subvert all of that for fun.)

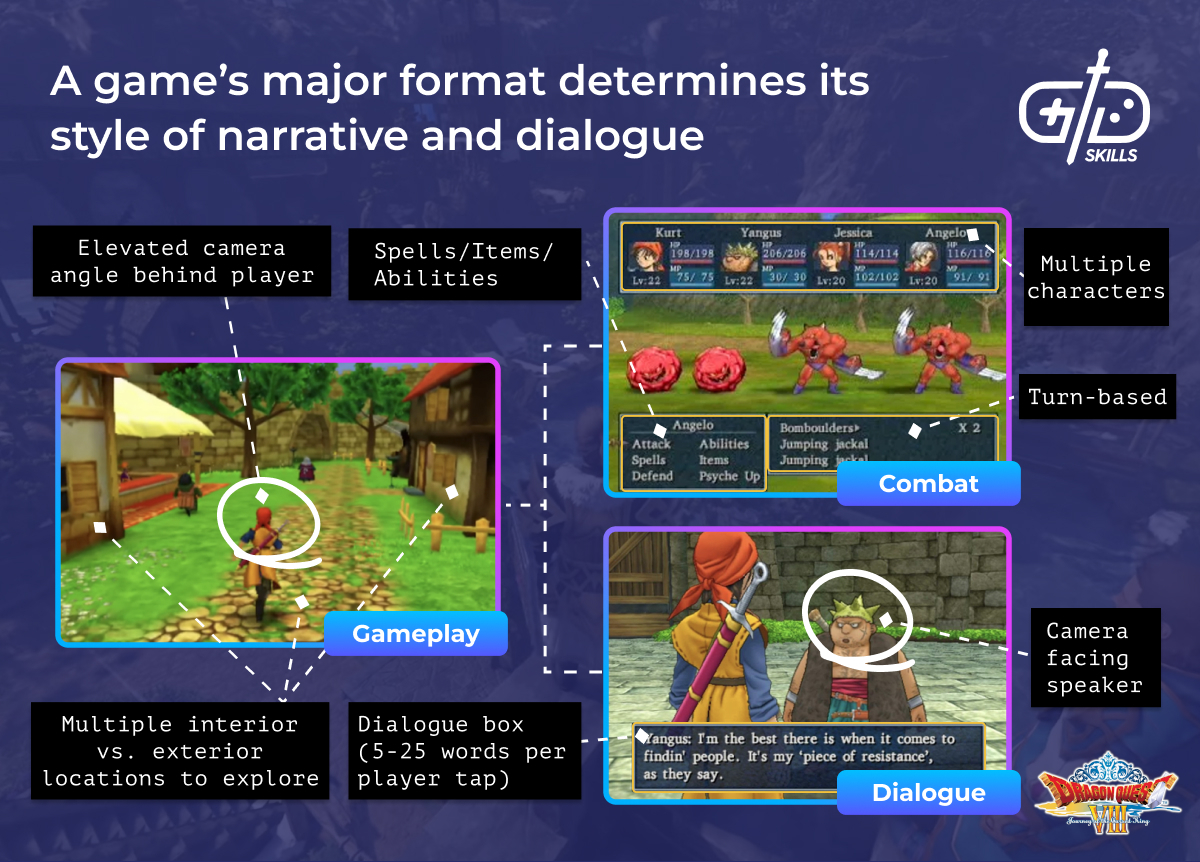

4. Determine major game format

Determining a game’s major game format (RPG, FPS, RTS, platformer, etc.) influences what kind of pace, storytelling techniques, and plot structures are most suitable. Each game genre comes with conventions and expectations like mechanical focus, standard camera angles, and pace of player interaction and input. RPGs tend to be expansive, slow-burning affairs with spikes of drama. FPS opt for high-intensity, moment-to-moment drama with an emphasis on diegetic narrative (narrative delivered with the player in control through radios, NPC mission briefings, and in-game screens).

How characters appear and interact in a game impacts the narrative system and dialogue. CRPGs, indie RPGs, and traditional JRPGs deliver dialogue through character portraits on the bottom of the screen. This presentation demands a focus on textual expression – the words alone convey the emotions. A full 3D game with AAA animated features conveys emotion with facial expression, body language, and voice acting. Different genres come with different expectations for dialogue. CRPGs use dialogue hubs, AAA RPGs feature NPC, location-based hubs with choices, and RTS and other strategy games often feature binary dialogue choices.

5. Find the major plot landmarks

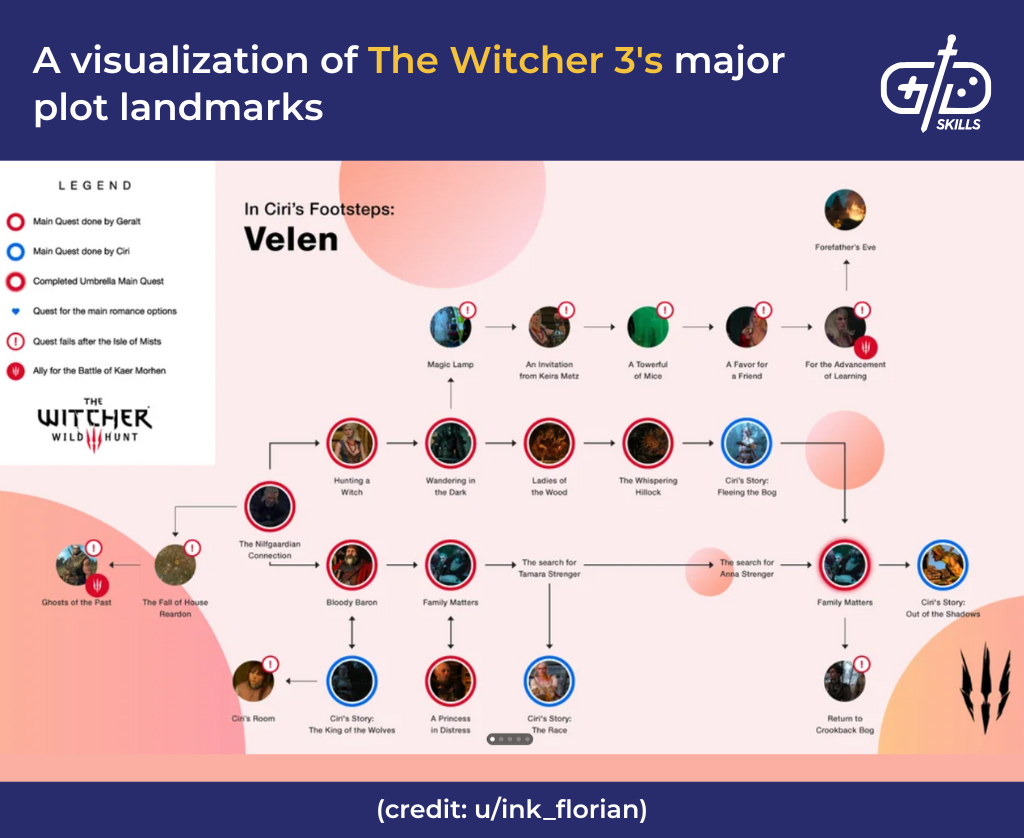

Outline the major plot landmarks in a narrative-based game to create a satisfying story arc that reflects the themes and tone of the project. Games that depend on narrative require coherent milestones representing player progression and motivation to continue. Typically, major plot landmarks are the fixed story elements that don’t respond to player input or choice (or do in a limited way). Creating a set of fixed, non-negotiable plot elements allows designers to experiment with non-linear elements for other parts of the game.

Gameplay plays a role in emphasizing plot landmarks through techniques like spiking difficulty or intensity before major plot moments or introducing new mechanics afterwards. Effective media reflects crystalized core elements of our life experience – payoff comes from hard work, relief comes when a crisis is averted, and sometimes we just get lucky. Video games differ from other media because players have agency. Player agency means plot landmarks must become temporarily portable scaffolds rather than fixed pillars in open world and non-linear games, meeting the player where they are, rather than forcing players down a single path. A linear game like Uncharted presents each scene in a fixed sequence with zero deviation, making for a movie-like cinematic presentation. Breath of the Wild, Skyrim, or The Witcher 3 must facilitate the player’s choice in when, where, and in what order to engage in the main quest.

6. Figure out the characters’ conflict during each crisis

Figuring out the characters’ personal and interpersonal conflict during every crisis reinforces the tension, makes each character more believable, and contributes to thematic consistency. Competing factions have a clear, predefined conflict in most conceivable crises. Within each faction, family, and friend group, however, motivations, though broadly similar, come from different emotions and manifest differently. Consider the difference between the idealistic rookie who joined the revolution to help the down trodden versus the widowed, middle-aged farmer who just wants revenge for his wife and kids.

Understanding why characters care on a moment-to-moment basis gives writers opportunities to reinforce tension and drama. This understanding allows for scenes and scenarios that test characters’ morality, force players to make difficult decisions, or reveal the differences between formerly sympathetic characters. Players understand the central conflict in part through playable and non-playable characters’ reactions to it. Establishing characters with a range of sometimes conflicting, sometimes overlapping values and beliefs makes narrative games feel more realistic.

7. Remember that mechanics exist to reinforce the plot

Mechanics in a narrative-heavy game must reinforce the story and the fantasy it promises. There’s no point in writing an epic script about powerful, interdimensional wizard factions if the gameplay comes down to flinging wet slugs at skinny chickens. Sure, story beats and seeing what happens to beloved characters remains the focus of many narrative-driven games, but gameplay and mechanics must echo the themes of the plot for maximum effect. Resident Evil 2, for example, reinforces its themes of horror, dread, and near-helplessness mechanically with restrictive controls, limited ammo, and small spaces.

Extending combat encounters or introducing meaningless fetch quests to extend a limited plot fatigues players and increases the risk of boredom. Players have an innate sense for when gameplay switches over from meaningful plot/character/theme-related engagement to unpaid virtual labor. The Witcher 3’s side quests are an illustrative example. One of the game’s core themes is “how does a person stay human when forced to deal with the monstrous?”. In many of the contract side quests, Geralt uncovers humans acting like monsters and monsters acting humane.

8. Develop story and mechanic beats that align

Develop story and mechanic beats to align what the player does, and what happens in the plot more broadly. New powers, level-ups, weapons, armor, and upgrades hit harder when they arrive at a point in the plot where they’re needed. Aligning the story and mechanics involves referring back to the game’s core theme. In Celeste, for example, as players climb higher, the mechanics become more challenging, the checkpoints more sparse, and the music less hopeful. Celeste’s tonal and mechanical changes reinforce the theme, syncing with the story told.

Story arcs where the mechanics shift alongside the plot work in games like Red Dead Redemption 2. Success in the early game leads to reputation, wealth, and power. By the time sickness and betrayal takes these things from you, Arthur Morgan’s core ability set feels worthless through consequences. Kingdom Come Deliverance 2 similarly uses story to strip your character developed in the previous game of his abilities and all his gear as the sequel begins. The mechanical effect works because the writing makes it do so.

How long does it take to write a game story?

The time it takes to write a video game story depends on the genre, platform, scope, and budget of the project. The detail the document attempts to capture also dictates how long a game story takes to write. A synopsis of the overarching story of a video game is significantly shorter than a full script covering dialogue, barks, cutscenes, and every scene outside of gameplay.

Genres dictate the length of game scripts. A story for an action-focused bullet hell shooter with minimal dialogue takes significantly shorter than a sprawling RPG, for example. Game development is not always a straight line to the finish, either. Writing teams regularly work throughout the development cycle to create dialogue around set pieces, maps, items, and interactions the designers have already created. When I worked on Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, for example, I worked within a section of the map to create fun quests and dialogue around weapons and locations the level and gameplay designers had created.

What makes a good video game story?

An effective video game story needs to fulfill one of two purposes (which sometimes overlap). The first is to provide an entertaining backdrop with archetypal characters to support a gameplay experience. The Mario, Sonic, Bionic Commando, and Crash Bandicoot series are examples. The second is to help build a compelling world, characters, and plot(s) that are fun to experience through gameplay. The Elder Scrolls, GTA, and Witcher series are examples.

Stories in both gameplay-focused and narrative-focused games are experienced rather than told. For gameplay-heavy games, this experience is background fun to the mechanical challenge. For a story-heavy game, the experience of revealing the story through gameplay is the whole point. This difference is crucial when designing a story for a video game. Without the direct control of a novelist or film director over the sequence of events, game writers for open world/non-linear games must focus on creating a thematically cohesive whole. When I worked on Age of Mythology: Retold, my job was often to create story beats and dialogues around gameplay events the designers had already created. Like many parts of game dev, the story is often in motion throughout the development cycle.

Is there a video game story template?

No, there’s no single video game story template used industry-wide. AAA game studios have their own proprietary software that integrates with the engine they use. Many AA and indie developers use film script format to outline cutscenes or fully linear dialogue. Where narrative systems are required for branching dialogue or non-linear experiences, writers create a system in Excel, PPT, or similar software with collapsible columns, where the branching choices, background info, facial expressions, and location data are included.