What is worldbuilding?

Under game development, worldbuilding is the part of game design that creates the fictional world or setting where the action occurs starting with the game writer. Depending on the project, this can include culture, society, politics, geography, technology, religion, zoology, and more.

A story’s primary focus is on what is happening. That said, where a story takes place significantly affects everything that happens within.

Let me explain.

Why is worldbuilding important in game design?

Stories of any kind (including games) are about resolving conflict and restoring order.

Here’s the thing:

Conflicts can’t exist in a vacuum.

They are inexorably linked to the places, cultures, and societies where they occur.

A compelling, convincing game world makes telling stories that hold players’ attention easier because the conflicts and tensions feel grounded.

Mass Effect is about Commander Shepard’s journey. However, consider how crucial its different places, cultures, and species are in creating inter-faction tensions and a sense of history.

Shepard’s story lands because the fiction supporting it is deep and interesting.

For example, the universe would seem duller and less inter-connected without the Krogan genophage or the Quarians’ complicity in creating the Geth.

Crucially, it would mean less nuanced backstories and motivations in characters like Wrex (pictured here).

Because here’s another thing:

Characters can’t exist in a vacuum, either.

Creating convincing factions, politics, geography, economies, and cultures gives you anchor points on which to hang believable character motivations, emotions, and reactions.

Consider two characters from popular games—Ulfric Stormcloak from Skrim and Sigismund Dijkstra from The Witcher 3.

With which of these characters can you make more connections to place, people, history, and culture? How does this affect our perception of that character’s depth and believability?

For most of us, the characters from The Witcher 3 resonate on more levels. This is not to criticize Skyrim. There are many things that the game does incredibly well.

But because Sigismund Dijkstra has a clear and compelling motivation derived from a well-thought-out loyalty to an interesting faction—he’s a truly memorable character. (It helps that he’s based on an equally nuanced literary character.

The same is true for other media—worldbuilding for video games shares much with novels, comic books, anime, film, and TV.

However, there are some medium-specific considerations to consider when creating game worlds.

What makes game worlds different from other fictional worlds?

Novelists and screenwriters retain total control over what their audience sees and hears. (And when they see/hear it.)

This is not the case with games.

In video games, the cadence of discovery is (in part) controlled by the player.

The pace of discovery varies from genre to genre, with open-world sandbox-style games leaving everything up to the player and linear, focused experiences narrowing the purview.

Either way, game writers must build their world in such a way that the players can’t break continuity or confuse themselves by discovering things in the wrong order.

These challenges are unique to interactive fiction.

That said, the pace of discovery is not the only way game worldbuilding differs from that of literature and screenwriting.

The fictional worlds of novels, films, and TV shows are designed to host the story—the fictional worlds of video games are designed to host the player.

A comparison between a film set and a playground is appropriate here.

A film set is effective at maintaining the fiction so long as the actors interact with it in the appropriate, established way (to deviate from this “breaks the fourth wall”, and is generally avoided):

- A film’s illusion is shattered if an actor opens a set door, revealing the sound stage behind it.

The playground metaphor is more appropriate than the film set when applied to games.

In a game, worldbuilding must be more than window dressing. Unlike films, games give players some freedom to explore and interact through their level design.

There’s an implicit expectation that the objects, spaces, and people presented in a game will hold up to a higher level of scrutiny and interaction than those of a film set.

Players can push and prod at the edges of the fiction in a way that’s unique to the medium. For this reason, worldbuilding for games must be more than an aesthetic or tonal backdrop.

It should create factions, places, technology, people, politics, and material culture that players can interact with meaningfully throughout their journey.

Worldbuilding for games must create more of a playground than a film set:

- The video game door must open to another part of the game or be locked. Why else could it exist?

Effective worldbuilding often resonates on an emotional level.

Players may not notice it explicitly, but they’ll feel something is wrong when a game world is poorly fleshed out or has weak internal cohesion.

The role of worldbuilding is to help the player forget they’re playing a game.

When players start asking questions that pick the fiction apart, it’s a sign that the worldbuilding isn’t working.

Questions like:

- Which faction is that and what do they want?

- Why are those guys so mad?

- Why are there so many locked doors and invisible walls?

- Wait, who are the bad guys?

Thinking your setting through before nailing down the specifics of the story can help you avoid these pitfalls.

Let’s break that process down into steps:

How to build a world for games

Step 1. High-level considerations

When building a world for a video game, I address these high-level considerations first:

Where: Where is your story taking place? Is it on Earth? If so, what period of history? Is it a planet in our solar system, another planet entirely, or a different universe?

How: How was this world/continent/city/space station/etc, formed? How long has it existed?

What: What’s the main source of conflict and tension in this place?

Who: Who are the primary actors in this conflict?

Why: Why are they in conflict with one another?

When: When is the conflict happening?

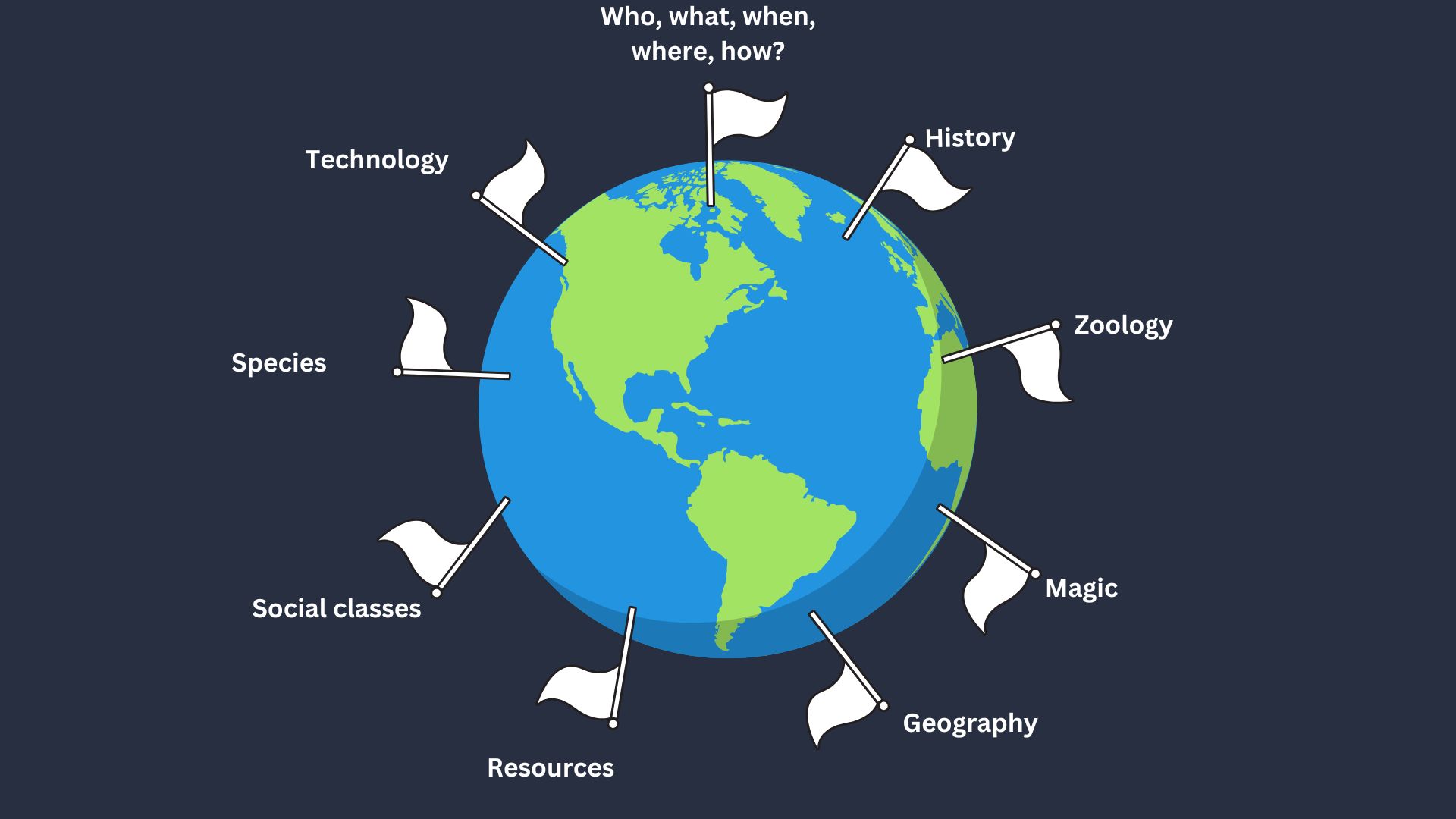

Once I’ve answered these major questions, I map out my world along eight vectors, breaking down each category on a 0-5 point system:

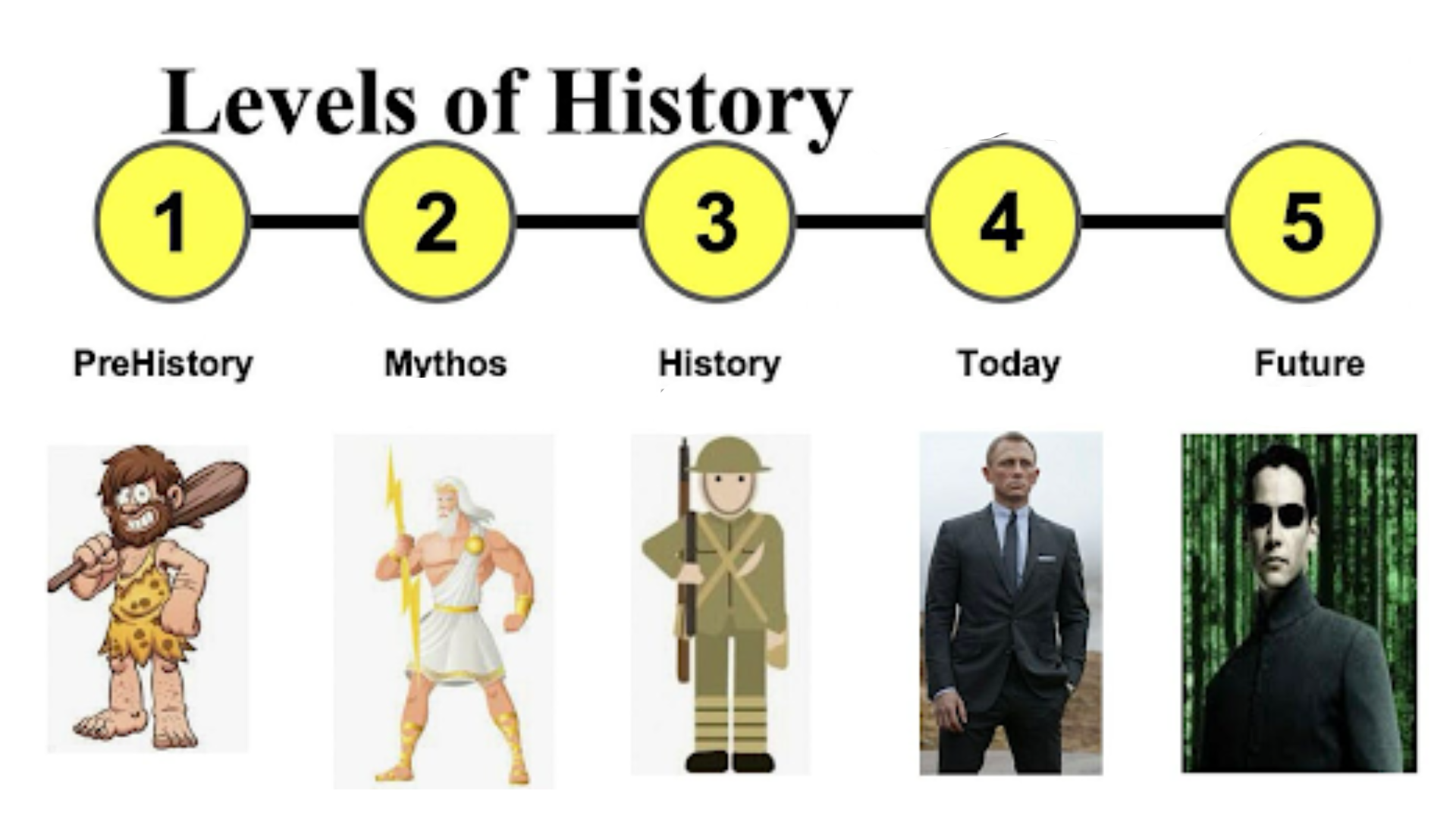

Step 2. History

History is the collection of stories a culture finds most meaningful, tied together by a timeline.

A convincing, fictitious world should have its own myths, tales, histories, and legends.

Tolkien’s Middle Earth is a good example of a world that existed before many of its specific stories were penned. The result is that Bilbo and Frodo’s adventures feel connected to a deep well of fantastical history.

Consider when your story happens on your world’s timeline and what preceded those events.

These choices affect the aesthetics, technology, and complexity of the setting but also help you plot your game world on a cohesive arc.

Analyze your game world’s history along these five points:

- Prehistory: This is the time before recorded history. Anything known about people from this time must be inferred from their material culture and archeological record.

- Mythos: This happened so long ago that it’s become folklore and legend. Truth and fiction mix in the realm of the mythical, offering writers lots of room for creativity and subversion of expectations.

- History: This is the stuff of record—written down (or otherwise recorded) for posterity. People endlessly argue over history’s minutiae, but the broad facts are generally accepted.

- Today: The current state of the world.

- Future: The world that has yet to happen.

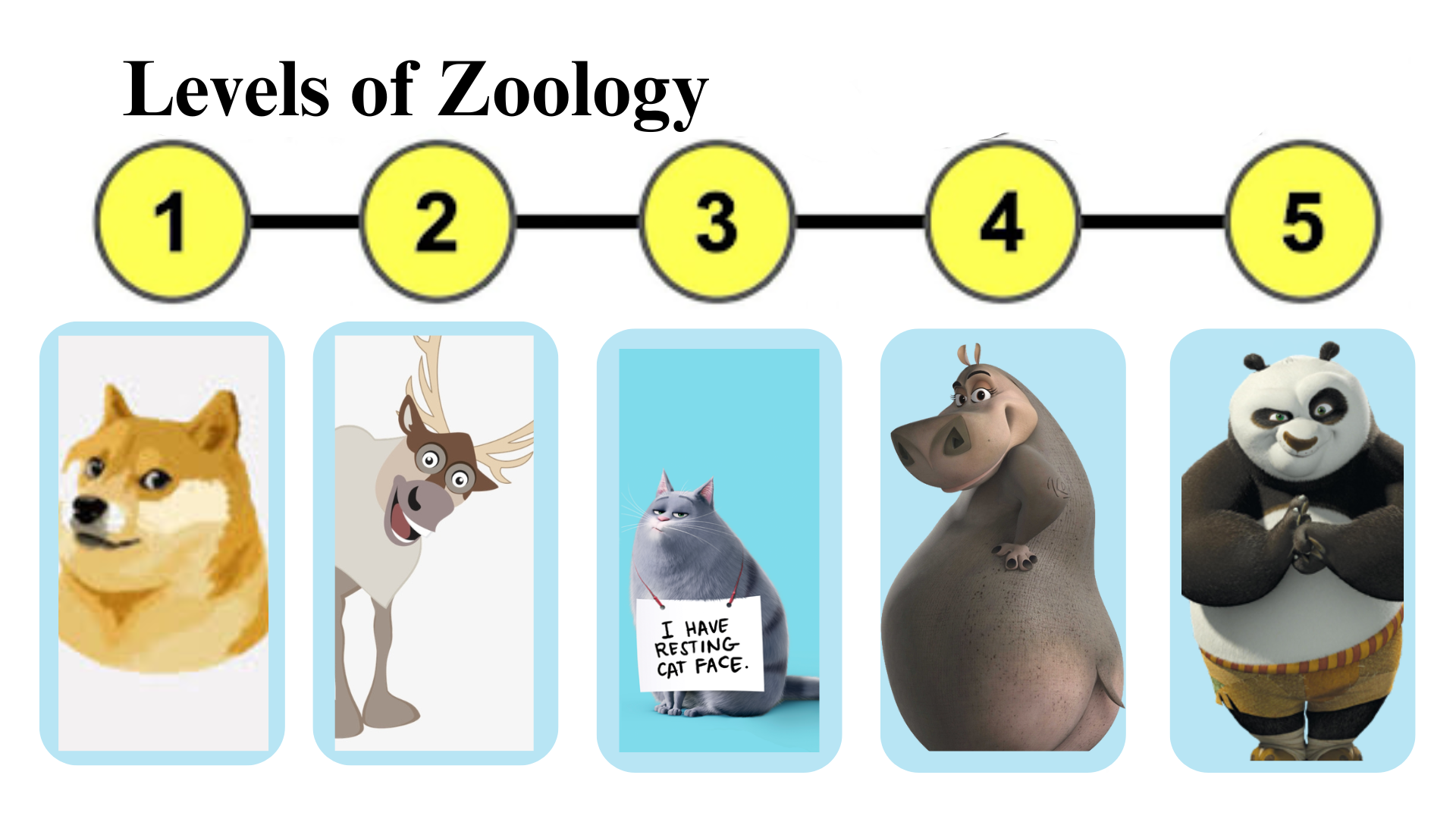

Step 3. Zoology

The zoology of your game world determines what kind of animals exist and how they interact with each other, the environment, and player characters.

This begs the question:

Are there animals in your game?

If the answer is NO, you can skip this section.

If the answer is YES, you must define these creatures:

1. Zero human traits: Humans and animals do not speak and interact sophisticatedly. (*Note: This is reflective of the world we live in.)

2. Some human traits: Animals understand some human language, respond with human-like facial expressions, and understand some humor. *Note: Sven from Frozen is a classic example. Sven walks on four legs and can’t speak, but he expresses human emotions and reactions.

3. Medium human traits: Animals speak fluently to other animals, but only when there are no humans present. (Or they only speak to one specific human.) *Note: The Secret Life of Pets, Toy Story, and The Lion King are great examples.

4. High human traits: Animals walk, talk, and emote with other animals like humans. *Note: Madagascar, Bugs Bunny, etc.

5. Full human traits: Animals have jobs and society and are in every way but appearance humans. *Note: Zootopia, Kung Fu Panda, and Cars.

Step 4. Magic

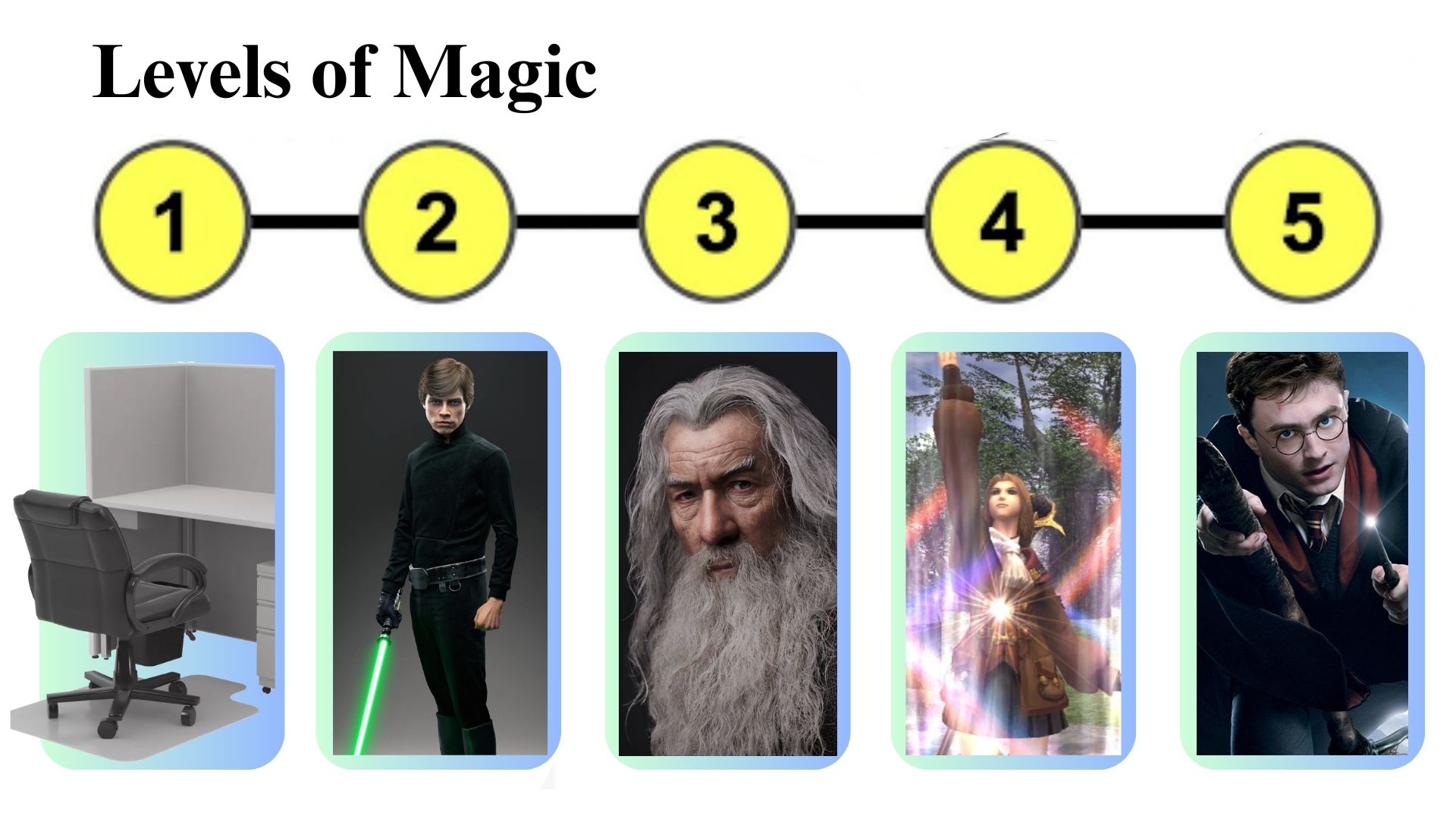

Next, you should establish the level of magic present in your setting.

We often think of magic as a factor in fantasy settings, but it also plays a role in many sci-fi, science-fantasy, and alternate-history settings.

The Force in Star Wars, Biotics in Mass Effect, and the powers and abilities in the Dishonored series are all examples.

Which of these five descriptions best fits your idea?

- No magic: Magic and supernatural abilities don’t exist.

- Low magic: Magic is rare. Sometimes exceedingly so. Most people go their whole lives without encountering magic, believing it superstition. *Note: An example of this is Star Wars. Many have heard about Jedi but have never met one. Less than 10% of the characters are Jedi.

- Moderate magic: Magic isn’t available to everyone, but it’s common enough that everyone knows about it, and some people have even gotten to see it firsthand. *Note: An example of this is Lord of the Rings.

- High magic: Magic is common. Perhaps everyone won’t be able to use magic, but magic is a normal part of life to which people have become accustomed. *Note: This is your Final Fantasy and Dragon Warrior Games. (each team has a mage, and wizards, witches, and warlocks are plenty).

- Dominant magic: Magic is everywhere, and life is defined by magic. People may be so dependent on magic that they could scarcely function without it. *Note: The best example of this is Harry Potter.

Step 5. Geography

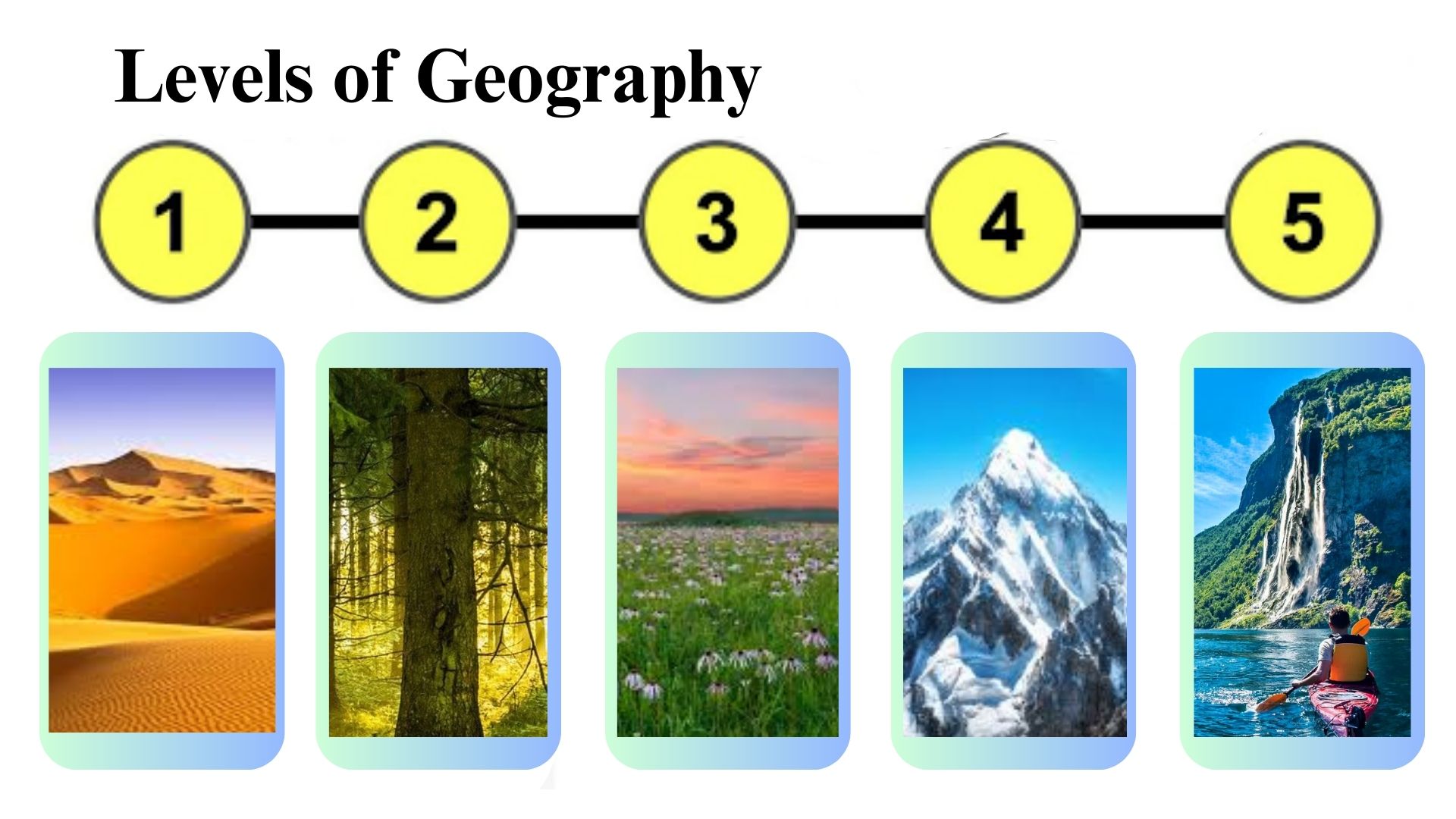

Understanding the terrain and biomes of your world is essential to your worldbuilding.

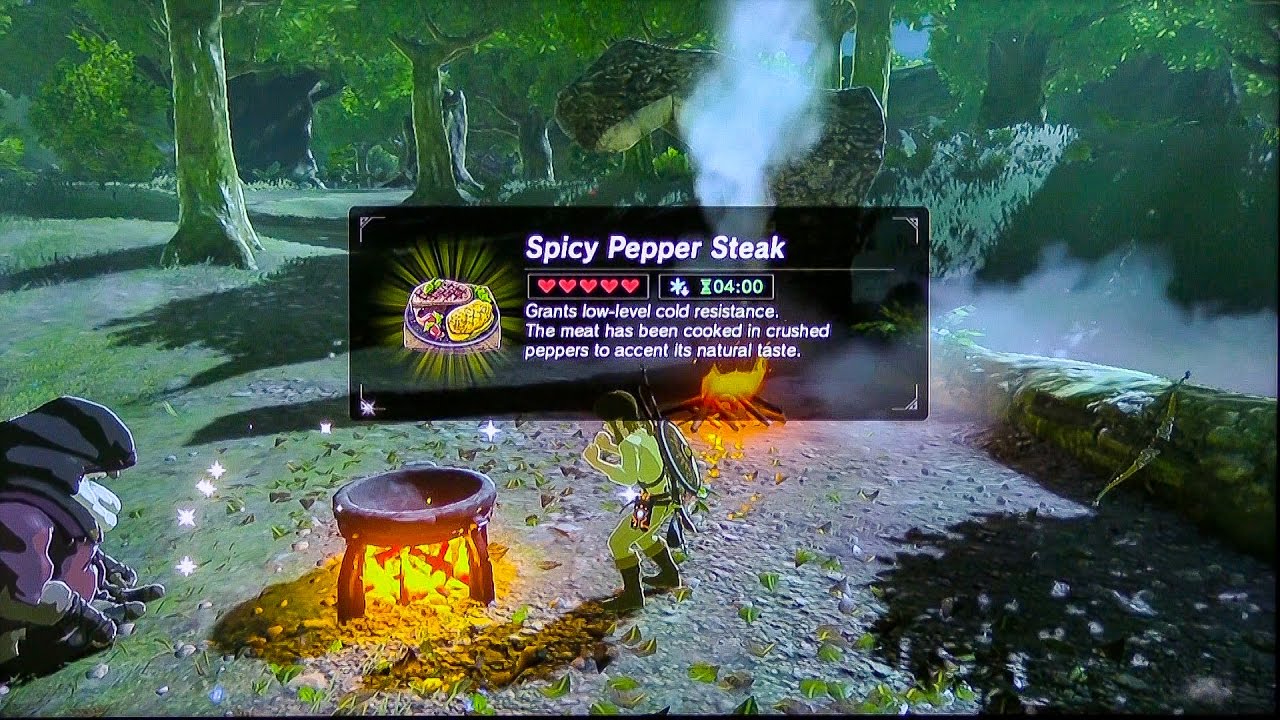

It allows you to accurately determine weather conditions and the various resources, animals, and other things available to a civilization. Wood? Fish? Minerals? Ore? Gold? Silver? Others?

When thinking of what biomes to include in your game world, it’s important to think about how they could be connected to each other, and not just by borders. By connecting the resources/weapons/etc. found in each one, your various biomes become part of a more symbiotic whole world.

For example, Zelda: Breath of the Wild (pictured below) did a great job connecting the biomes through the resources found in each via their weather and cooking systems’ design. (Items found in hotter climates when cooked kept you warm in colder ones, and vice versa. Also, Ice weapons had advantages over desert enemies.)

Unlike Zoology and Magic, we aren’t determining if geography exists; we are determining what types. (If there’s a wacky liminal experience out there that does away with the need for geography altogether, let us know!)

- Deserts: Are there deserts? Can you cross them? Who or what lives there? What resources can you find there?

- Forests: Are they dense? Tropical? Rain forests? Sources of lumber? Food? Do evil things live in them?

- Prairies: On the prairies is there Farming? Cattle? Villages?

- Mountain: Do they divide nations? Are they obstacles? Are there resources?

- Waterways: Oceans? Rivers? Lakes? Waterfalls? How much? Is it 80% water and 20% land like Earth?

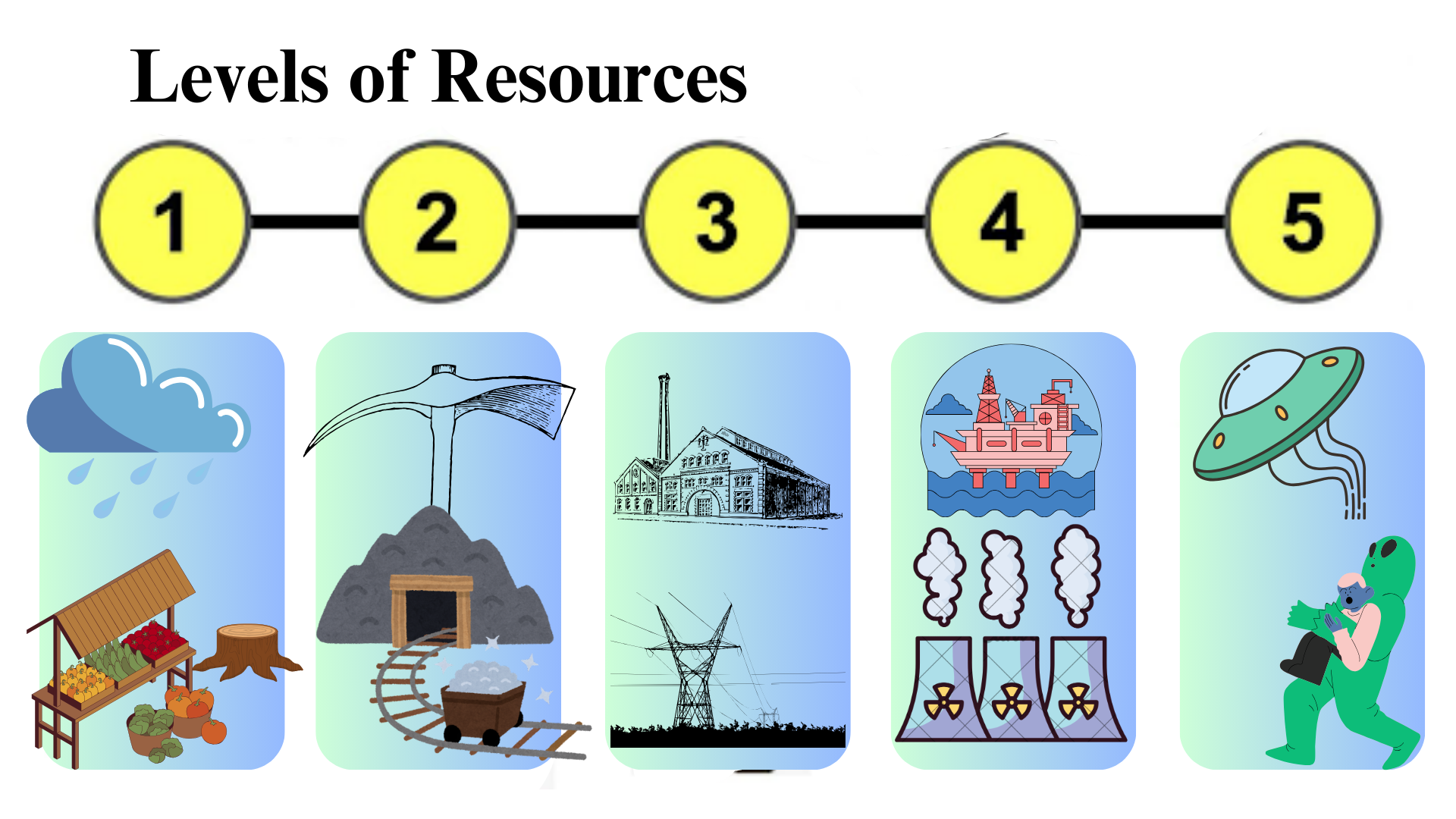

Step 6. Resources

Once you have your world’s biomes, you must determine what comes from these biomes.

This can be a critical consideration in craft-heavy MMOs and RTS games, where access to resources is an important part of gameplay.

That said, even in games where the resources aren’t an active part of the experience—making them feel believable helps immersion.

For example, The Outer Worlds’ Saltuna Factory and C&P Boarst Factory don’t offer players unique, exciting resources. Still, they deepen immersion by making the game world feel lived-in (and kind of gross!).

Which level of access to resources best describes the societies of your game world?

- Renewable natural resources 1: Wood, Plants, Fruit, Vegetables, Water, etc.

- Renewable natural resources 2: Gems, Metals, Crystals, etc.

- Non-renewable natural resources 1: Fire, Electricity, etc.

- Non-renewable natural resources 2: Gases, Nuclear Energy, Oils, etc.

- Non-natural resources: Alien, Magical, New, other.

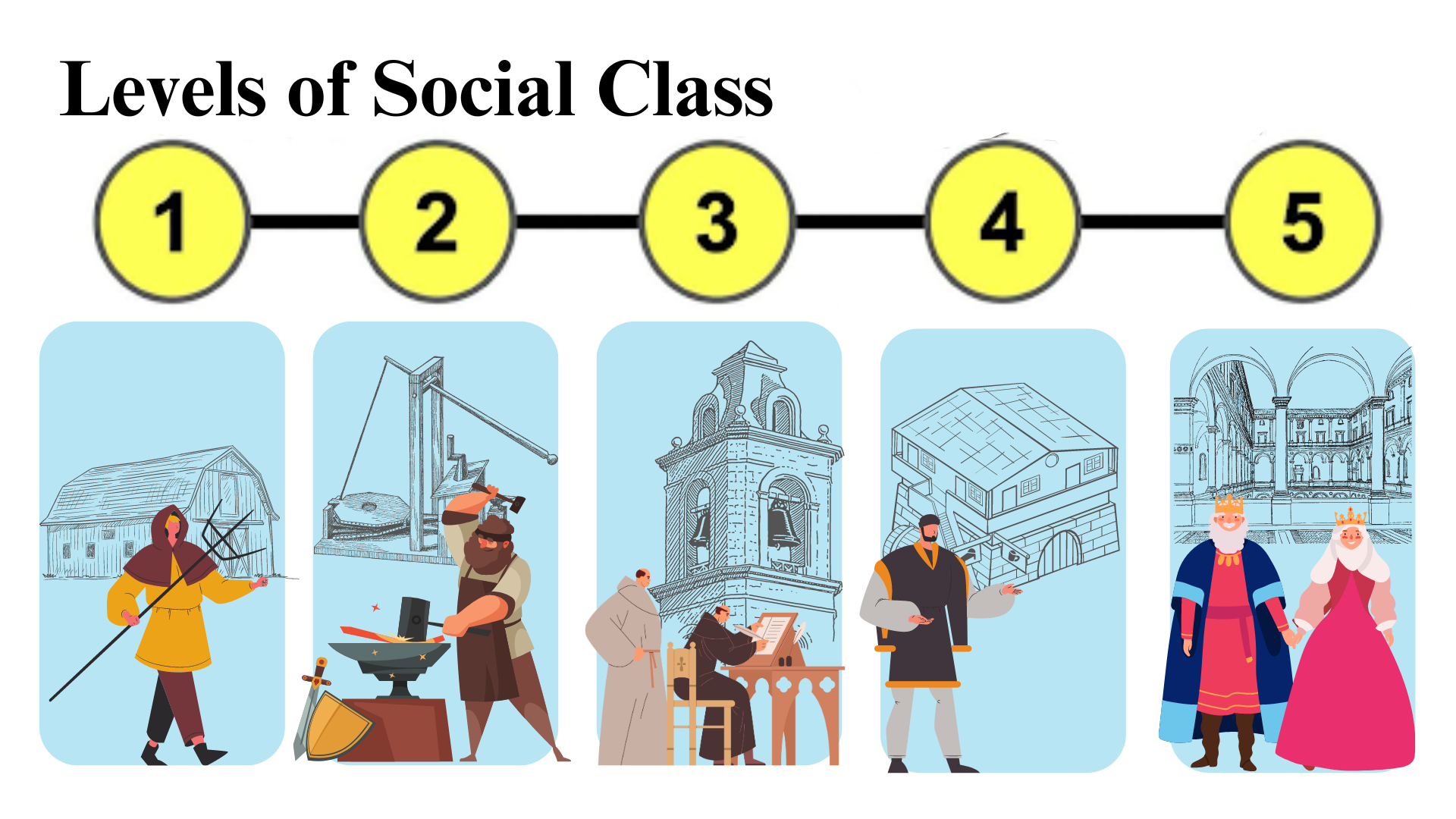

Step 7. Social classes

Social classes (and their relationships to one another) form an important touchstone in most fiction. Factional tensions, interpersonal relationships, and cultural norms are all informed by an individual’s place in the social hierarchy around them.

Consider how different 1984 or A Handmaid’s Tale would feel if their socio-political elements were removed.

Even within games, there are many examples where class and hierarchy are front and center in the narrative design.

Without their social commentary, it’d be impossible to recognize games like the Tales series or Papers, Please (pictured here).

Choosing the form of social organization for your game world is step one.

Is it a Kingdom? An Empire? A Democracy? Dictatorship? Oligarchy? (A secret society ruling things.)

Once you have the form of social organization settled, consider which of the following classes appear and how they relate to each other:

- Peasants/poor: This is the lowest class in society

- Working class: The blacksmiths, chefs, doctors, barbers, bartenders, bakers, etc.

- Lower/middle class/commoners: The accountants, librarians, small business owners, etc.

- Middle class/noble: The clergy, land owners, business owners, managers, etc.

- Upper class/royalty: The princesses, princes, politicians, Kings, Queens, judges, etc.

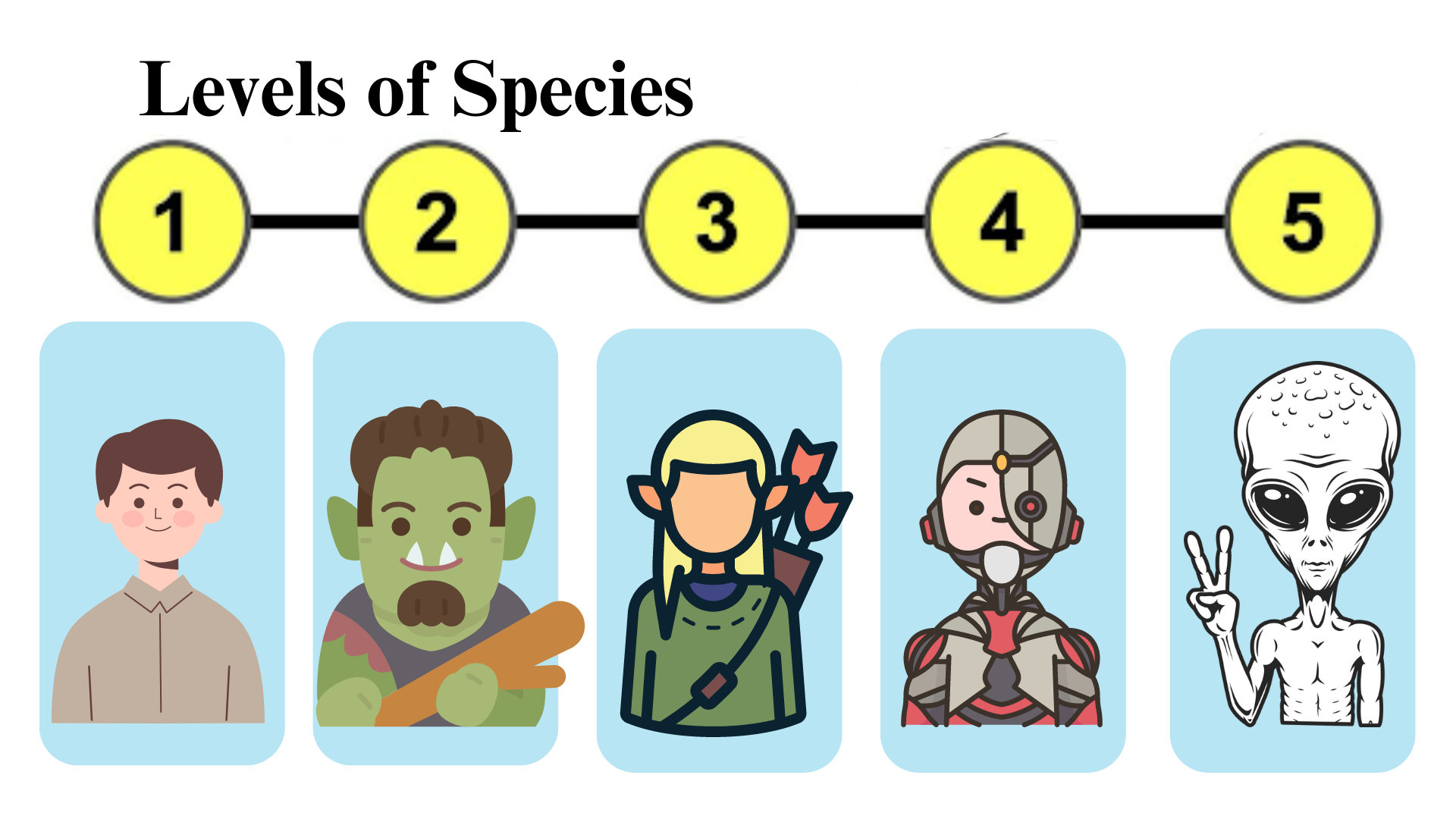

Step 8. Species

Characters are not only divided by classes but also by race and species.

How will players differentiate between the different species of your game world? What are the relationships between those species?

Tolkien’s Middle Earth stands as the inspiration for many settings’ inter-species relations, but other writers have contributed some fascinating, less thoroughly mined dynamics.

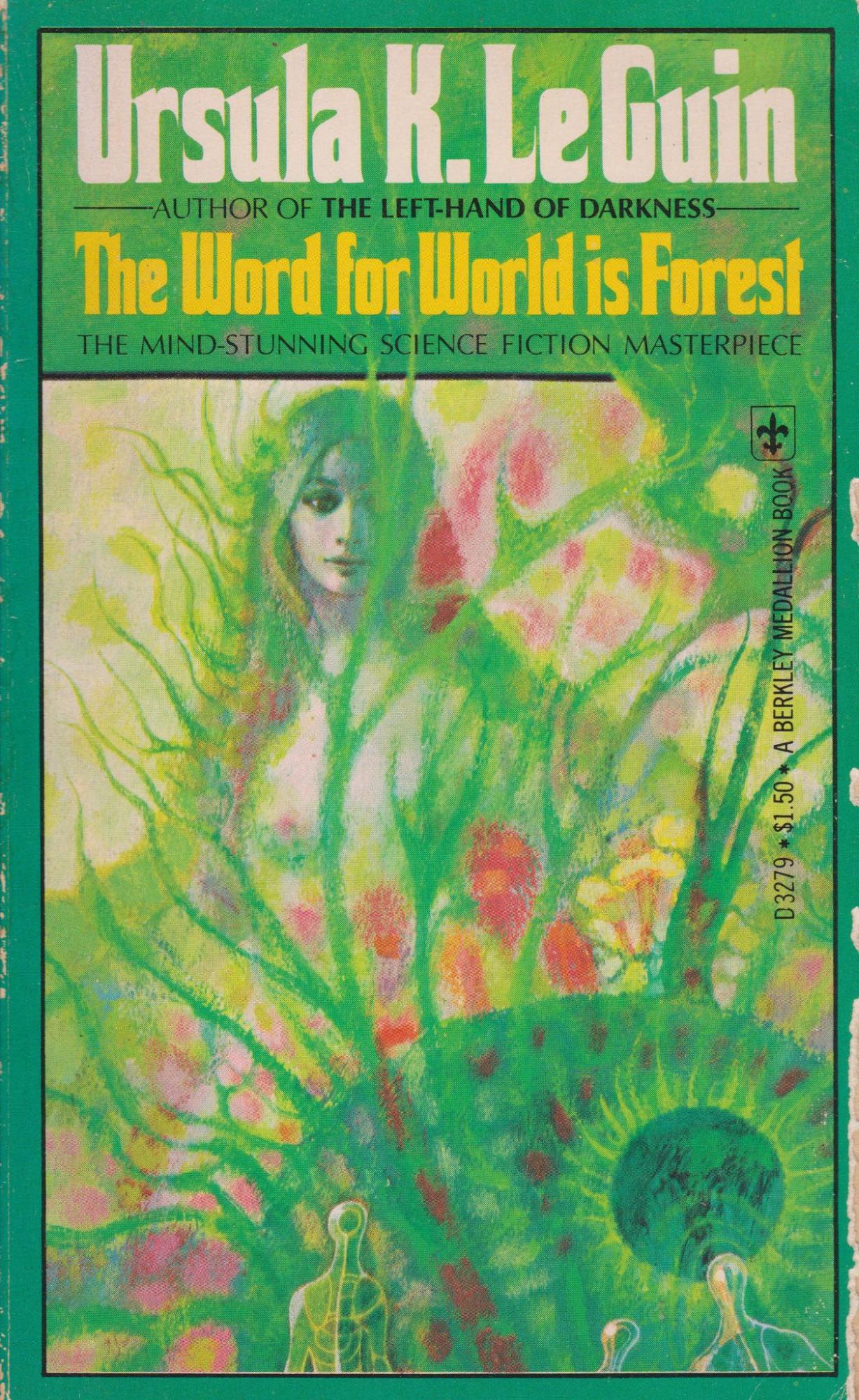

The relationships between species are pivotal (and unique) in work like Larry Niven’s Ringworld series or Ursula Le Guin’s The Word for World Is Forest (pictured below).

Your choices should only be limited by your imagination, but the following list can help you plot the level of species variety in your setting:

- Humans: Various cultures, races, and genders.

- Ogres: Various hybrid humanoid species—ogres, cyclops, mole-people, etc.

- Elves: Human-like creatures with enhanced abilities and skills.

- Hybrid: Humans mixed with other species, Cyborgs, Minotaurs, etc.

- Alien: Otherworldly, zombies, aliens, ghosts, undead, etc.

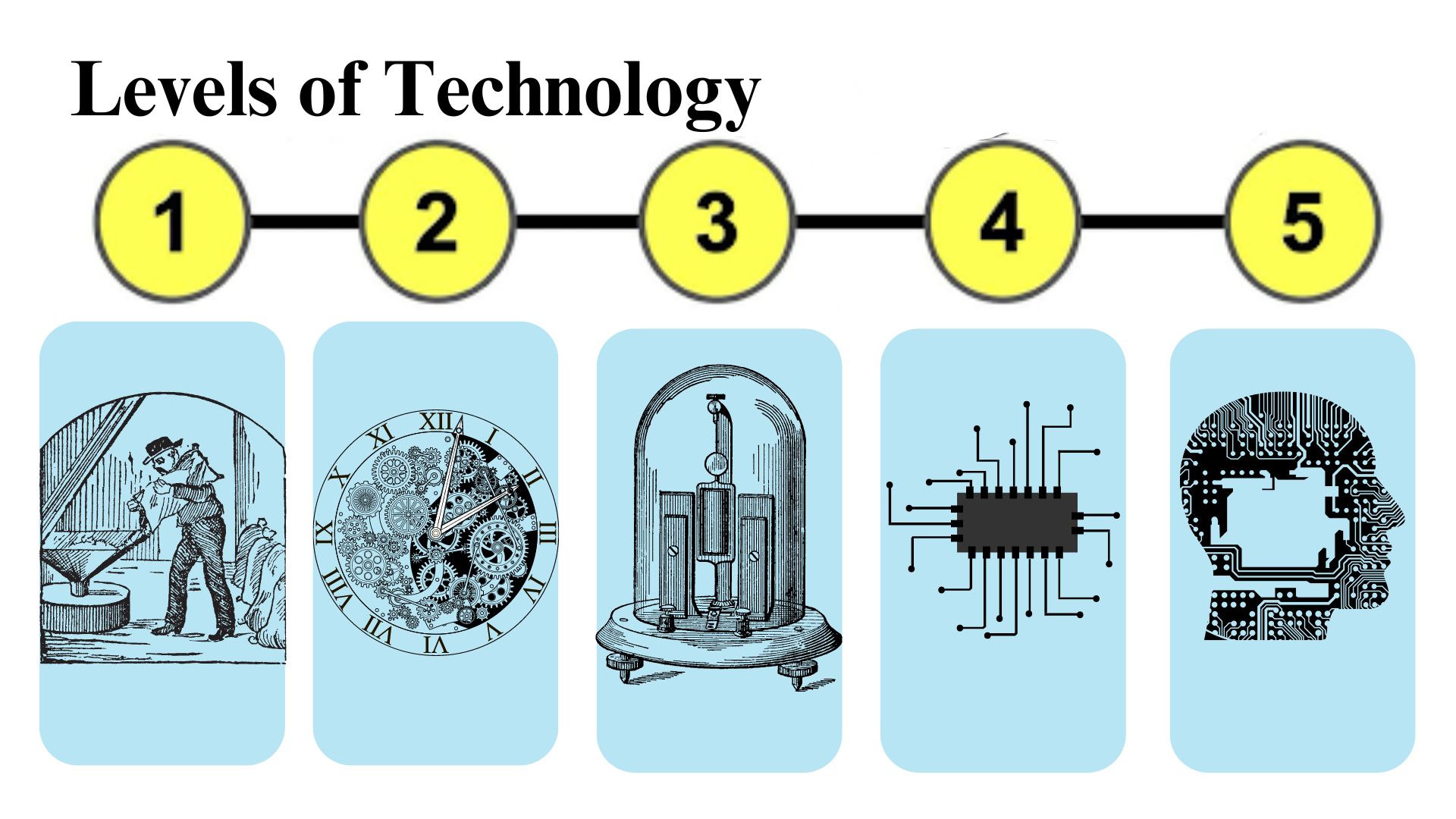

Step 9. Technology

Technology comes in various forms, and it’s important to list and determine what appears in your game world.

For example: Is there gunpowder or guns? How advanced? Flintlock or automatic weapons?

Technology sets the tone and determines the range of options available to the player. (Note: This should always be connected to your game’s crafting system.)

For example, Kingdom Come Deliverance would have required some serious adaptations to its depictions of technology if the developer had decided to set the game in Bohemia in 2003 rather than six hundred years earlier, in 1403.

Though not a one-to-one recreation of early 15th-century material culture in every way, players appreciated the dedication to historical accuracy in Kingdom Come Deliverance’s weapons, armor, buildings, and technology (pictured below.)

If your game is based on history, players will expect some level of realism in its depiction of technology.

However, even if your game is set in a fictional universe, it’s worth considering the technology level along the five-point system.

Fantasy settings usually have some kind of historical analog (or use a mix of several eras). Science fiction or alternate history settings often extrapolate their technology based on contemporary innovation.

Which level of tech best describes your idea?

- The Pre-mechanical Age: 3000 B.C.- 1450 A.D

- The Mechanical Age: 1450–18403

- The Electromechanical Age: 1840–19404

- The Electronic Age: 1940–20195

- The AI (artificial intelligence) Age: 2020 — Future

*Note: Let’s not forget Steampunk, Victorian, a combination of multiple ages, etc. This kind of mix of historical influences has been used to great effect in games like Bioshock (pictured below.)

6 worldbuilding tips to improve your players’ immersion

Each of these strategies can help you fully flesh out your world and hold your audience’s attention:

1. Establish motivations

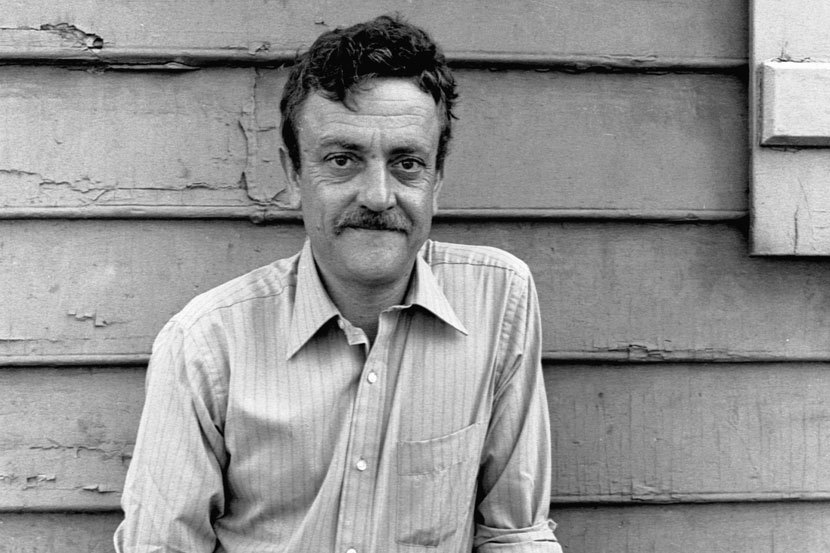

Kurt Vonnegut offers the following advice in his 8 Rules For Writing:

Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water. – Kurt Vonnegut (pictured here)

While this tip is clearly about character writing, it can be adapted and applied to worldbuilding.

When creating a fictitious world, each faction, species, and race should have a coherent motivation derived from the setting’s history.

Many veteran D&D Dungeon Masters claim that all they need for a successful campaign are three factions with clear, logical motivations that overlap and compete. The story takes care of itself once the players get in the mix and start picking sides.

This brings me to a key point about reality (and effective attempts to immerse people in fiction):

Everyone has a side.

Good worldbuilding makes conveying realistic loyalties, enmities, and betrayals easier because we can understand the motivations behind every action.

Players should find it easy to understand why conflicts and tensions exist in a setting. Crafting factions with clear ideologies, cultures, practices, and goals makes this possible.

2. Build from mechanics up (where applicable)

Every project is different. In some cases, the gameplay mechanics don’t significantly affect worldbuilding.

However, consider strategy titles like Stellaris or the Crusader Kings series (pictured below).

In these mechanics-heavy games, worldbuilding must fill the setting with believable fiction for resources, factions, conflicts, and intrigues.

In a historical setting like Crusader Kings, writers must adhere to some historical accuracy and fill the game with interactive elements.

Action, platform, and puzzle games also need worldbuilding to do some heavy lifting occasionally.

For example, the pits of lava, verticality, spawning monsters, and teleporters are explained by worldbuilding, but they also facilitate the strongest gameplay mechanics in Doom Eternal (pictured here.)

The game world of Portal is built around the title’s unique traversal and puzzle-solving mechanics.

Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom also uses worldbuilding to introduce new mechanical options like the floating islands and zonai. These options then come to define the experience as players build their own contraptions to traverse the space.

Sometimes, a game’s mechanics are so pivotal to an experience that worldbuilding must work around the gameplay—creating reasons for traversal challenges, combat engagements, puzzles, and more.

3. Use environmental storytelling

Environmental storytelling intersects with worldbuilding because both concepts exist outside of the classical forms of exposition.

The burned-out buildings of Fallout, the cramped tunnels of the Metro series, and the razed hinterlands of The Witcher 3 all tell stories without dialogue, subtitles, or direct-to-player messaging.

Each room tells a story about the people who once lived there and those who’ve huddled in the space for shelter in Fallout 4 (pictured below.)

Metro’s squalid tunnels tell a story about survival, resilience, and humanity’s ability to persevere despite the odds. (Reading Dmitry Glukhovsky’s Metro novels makes you appreciate how far the game’s environmental artists went in this regard.)

As you approach towns and villages in The Witcher 3, burned fields, gibbets, corpses, and crows fill you in on what’s going on in the area.

The tone is set without any traditional exposition, and players know what to expect.

4. Keep it grounded

Keep it grounded may sound like odd advice for creating the fantastical and futuristic worlds of many video games—but bear with me.

If the Jedi mind trick worked on every creature in the Star Wars universe (or magically worked every time it was needed to progress the plot), it would seem somehow less realistic.

If putting on the one ring made Frodo invisible, powerful, and impervious to harm, we’d see a very different, much shorter tale in The Lord of the Rings

Therapist: Buff Frodo doesn’t exist. Buff Frodo can’t hurt you.

Buff Frodo:

Players don’t appreciate their progress being impeded by some arbitrary-feeling scientific/magical MacGuffin.

The impediment to progress and the key to game progression must feel grounded in the fiction’s history, culture, and logic.

Audiences (and gamers) rarely appreciate when a long-established parameter of your fiction is obliterated because the plot requires it. (Tracking ships through hyperspace in The Last Jedi is one example.)

When worldbuilding, picture what the people of that setting consider the hard and fast rules of existence to be. Anything that breaks the expectations of regular people in your fictitious world should be exceedingly rare—just like reality.

5. Don’t give all the answers

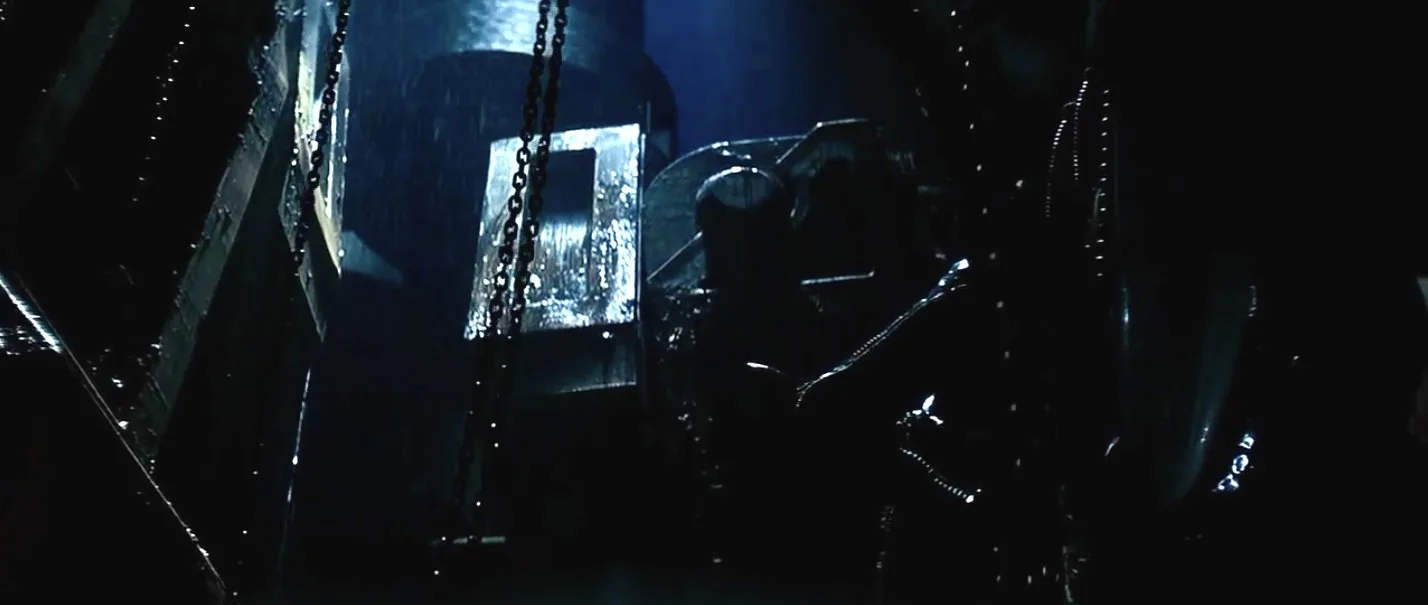

Do you know the scene close to the end of Alien where the xenomorph and Jonesy (the ship’s cat) are loose in the cargo area?

Let’s analyze that.

Why are there huge industrial chains hanging from the ceiling?

Why is water dripping from above?

The truth is that neither of these questions is addressed—and it doesn’t matter!

The rattling chains and dripping water add tension to an already tense scene, and they’re sufficiently industrial that we don’t immediately flag them as out of place in the Alien universe. (Pictured here.)

D&D DMs sometimes talk about the “rule of cool” when deciding if player actions are possible or not. The idea is that if the action contributes to the story without breaking the fiction—allow it.

The same rule can be applied to worldbuilding.

6. Design your game world with expansion in mind

When I am designing a game world for mobile games, the first question I ask the producer is:

What is my dragon?

The game might not have a dragon in it or even be a fantasy game, but I’m trying to determine what the highest level weapon/enemy the player can encounter is.

The fact of the matter is when you are designing a mobile game, you are not designing it for only year 1, and that producer—you’re designing it for five years and three producers from now.

If your game starts with LEVEL 2 (on a scale of 5 above) MAGIC, then you need to understand that by year 3 of the game, you will already be at LEVEL 4 MAGIC due to the player’s progression, spending, challenges, etc.

You have to plant the seeds for expansion early on in your worldbuilding. Because if you don’t allow for expansion of technology/magic/dragons/new biomes/new species then when your players run out of challenges or things to collect, and you start adding things that don’t fit within the established lore… the immersion is lost, and your players know it’s all about the money and you’ll lose them too.

Writing with expansion in mind is advice that can be applied to worldbuilding for other mediums, too.

There are countless examples of TV series with first seasons that appear to mine their setting thoroughly of good stories. This is often because the writers weren’t thinking beyond an initial run.

The superior, D&D-inspired worldbuilding allowed for many seasons of fresh content without repetition or barrel-scraping from Adventure Time (pictured below.)

What are some worldbuilding examples?

Every piece of fiction engages in worldbuilding, even if it borrows the majority of its reference points from reality.

However, the video game worldbuilding examples that stand out tend to come from fantastical, futuristic, or otherwise different-from-reality settings.

Fable

The Fable series’ first iteration in 2004 was criticized for its director’s infamous over-promising of features.

Despite criticism at the time, Fable is widely regarded as a classic today.

I’d make the case that where Fable truly excelled (and why it’s popular today) is its excellent, idiosyncratic worldbuilding.

Yes, Albion was a quasi-medieval setting with all the Tolkienesque trappings—but it also gave players a sense of lived-in history that worked for Fable (pictured here).

The player’s story in Fable felt like it was happening at a point in the wider game world’s timeline. Characters like William Black and the antagonist Jack of Blades link the player’s actions to a coherent history revealed to the player without info-dumping.

This sense of a coherent timeline is reinforced as the sequels progress through analogs of European history in a way reminiscent of Joe Abercrombie’s work.

Mass Effect

John Shepard’s story is a fairly typical hero’s journey through a distant, fantastical future. And while you could make the argument that its worldbuilding isn’t the most original, the Mass Effect trilogy does an excellent job of setting up its factions, conflicts, races, and intrigues.

Each race features a distinct visual design, a coherent history, and various motivations and loyalties that overlap and compete. It also avoids the pitfall of an overly simplistic antagonist by including Saren as a nuanced, emotionally reactive enemy to complement the mechanical Geth.

Mass Effect’s worldbuilding includes a sense of baked-in history thanks to the Prothean ruins and technology, and the game’s beautifully voiced codex entries flesh out humanity’s history since the dawn of our space age.

Crucially, Mass Effect sets up its world in such a way that the player’s journey becomes the highest stake story in the galaxy.

Worldbuilding plays a vital role in setting up the stakes for your protagonist in any kind of fiction. Mass Effect demonstrates this principle well without resorting to mystical “chosen one” tropes.

How to start worldbuilding with no experience

The first steps into anything new are the hardest.

The TLDR version of everything I’m about to say is this:

Everyone starts somewhere, so start the thing, enjoy the process, and then finish the thing.

That said, here are some reasons why I think you can build a world more easily if you tear down a few barriers that may exist in your mind:

Everyone starts somewhere

When it comes to worldbuilding, originality is great but not a requirement.

Many first-time writers get fixated on coming up with settings, factions, geography, and aesthetics that are one hundred percent unique.

The truth is, many of the most beloved fantasy and science fiction settings are themselves pastiches of other work.

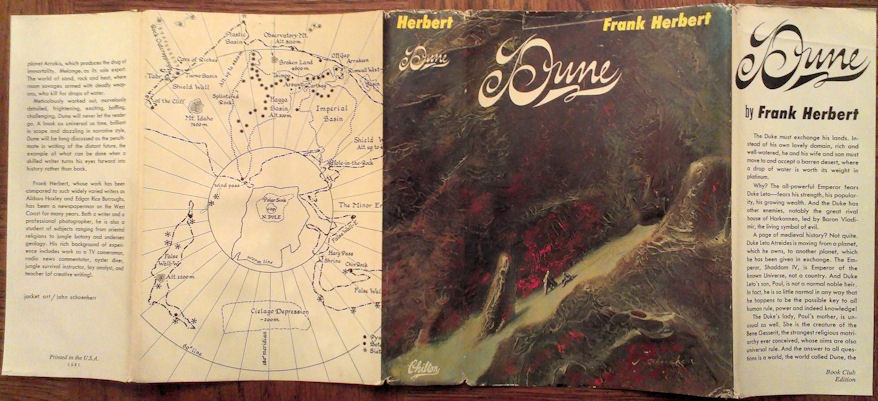

Frank Herbert counted 37 clear and distinct similarities to Dune in the first Star Wars movie. George Lucas even concedes he’d just read Frank Herbert’s novel (pictured below).

While Mr Herbert’s frustrations are understandable, they aren’t necessarily valid.

We can’t all dream up sectarian resource wars on far-flung planets, accessed only through a mysterious guild of spice-addicted spacefarers.

Herbert himself was heavily influenced by Lesley Blanch’s The Sabres of Paradise, a narrative history telling of a conflict between caucasian Muslim tribes and the Russian Empire in the 19th century.

To my knowledge, Ms Blanch never complained about any similarities.

Using your influences as a jumping-off point is one hundred percent OK. The more you write, the more you will come out in your work.

Top-down or bottom-up?

Some writers start with the minutiae of their main character’s story and then build the wider world outward from there. Others prefer to create factions, cities, politics, and other details before working down to the stories of individual characters.

There’s no right or wrong way to do this, but the two approaches yield different results. Tolkien’s Middle Earth is probably the best example of a setting that existed before its most beloved story was written.

The effects on the prose and narrative are clear—every other line in Tolkien hints at a wider world beyond the events on the page, and the protagonists’ story feels like one part of a longer narrative. On your first experience of The Lord of the Rings, it’s clear the text will reward multiple readings and ancillary research.

Depending on how fantastical your game’s setting is, the top-down or bottom-up approach may work better.

Consider a slightly futuristic military shooter, for example. In this case, the worldbuilding might have to do some light-lifting to explain some futuristic technology and made-up factions, but it doesn’t require a total top-down effort.

Let the project, your instincts, and the pursuit of “fun” guide you.

How to get better at worldbuilding

If you’re serious about writing and designing game narrative professionally:

Here is the 13-week live project-focused game writing bootcamp I intentionally designed for narrative designers and game writers aiming to get hired or junior professionals looking to upskill.

In this bootcamp, I’ll personally guide you to create industry-level, portfolio-ready projects using proven concepts and frameworks, including those covered in this guide.

As a member, you’ll also get

- Examples and demonstrations from AAA, AA, and mobile games I’ve shipped

- 7 guest instructors from various disciplines to share how they collaborate with game writers in real-world settings

- 1 adjunct instructor with AAA narrative design leadership experience to provide additional guidance

- A marketing specialist with 15 years of expertise to help turn your projects into a standout portfolio piece that gets interviews

- Small group to ensure focused, personalized attention for every participant

- Members-only free hosting, personalized subdomains, and proven templates to showcase your portfolio and retain the right attention

You can view the full bootcamp curriculum, instructors, and more details here.

Worldbuilding questions to guide your ideation

Sometimes, answering a question feels easier than generating an idea from nothing. For this reason, I’ve included a list of questions you can apply to your setting.

Consider these a jumping-off point. There are countless questions that you can come up with to focus your ideas at this point in creation.

- How many continents/islands does this world have?

- Which species/kingdoms are there?

- What is each island’s biome like? (Ice, swamp, fire, desert, etc.)

- Are there interesting landmarks/points of interest (POI)?

- What could spawn conflict in this world?

- How did the nations come to their current form?

- Are there contested borders?

- Do people have enough resources? (Food, water, wood, etc.)

- What technologies exist? (Magic? Teleportation? Inventions?)

- Are there specific cultures?

- Is there free trade? Alliances?

- Are people thriving or struggling in this place?

Useful worldbuilding tools to help with your process

As video games, TTRPGs, fantasy, and science fiction continue to grow, the process of worldbuilding has developed more of a framework.

Nowadays, lots of tools exist to help writers keep track of ideas and share them with collaborators.

Many offer a free version or a trial period. Some are entirely free.

Worldbuilding software

Fantasia Archive: Fantasia Archive is a free, offline worldbuilding tool. It’s powerful, feature-rich, can run on modest hardware and is funded by the creators’ Patreon.

Plotter: Plottr acts like a digital corkboard, allowing writers to map out their worlds across various categrories. It’s well-reviewed and allows writers to work offline, but doesn’t offer a free plan.

Worldbuilding websites

Kanka: Kanka is a worldbuilding site mainly geared towards managing tabletop RPG campaigns. That said, it features interactive maps, calendars, timelines, and more. Kanka also has a free version.

World Anvil: World Anvil is one of the best-known, most polished, and feature-complete worldbuilding tools out there. There’s also a limited free version available to try.

Campfire: Campfire is a comprehensive reading and writing platform for genre fiction. It includes tools and features that help you keep track of factions, geography, history, and politics, Campfire also includes some generative tools that allow you come up with new ideas on the fly. A free version is available.

Worldbuilding books

Wonderbook by Jeff Vandermeers: Jeff Vandermeers classic covers everything you need to create memorable science fiction and fantasy settings. The book is also well-written, full of examples, and funny in its own right.

On Writing and Worldbuilding by Timothy Hickson: Timothy Hickson’s book looks at worldbuilding in a pragmatic, plot-focused way.

How to Write Science Fiction & Fantasy by Orson Scott Card: Orson Scott Card covers creating memorable factions, politics, and conflicts by defining the core elements of science fiction and fantasy stories.