- Resume

- LinkedIn profile

- Portfolio (starter portfolio with one or a few projects is fine)

- Team project experience

- Playtests and feedback on your projects

- Experience with a game engine/coding

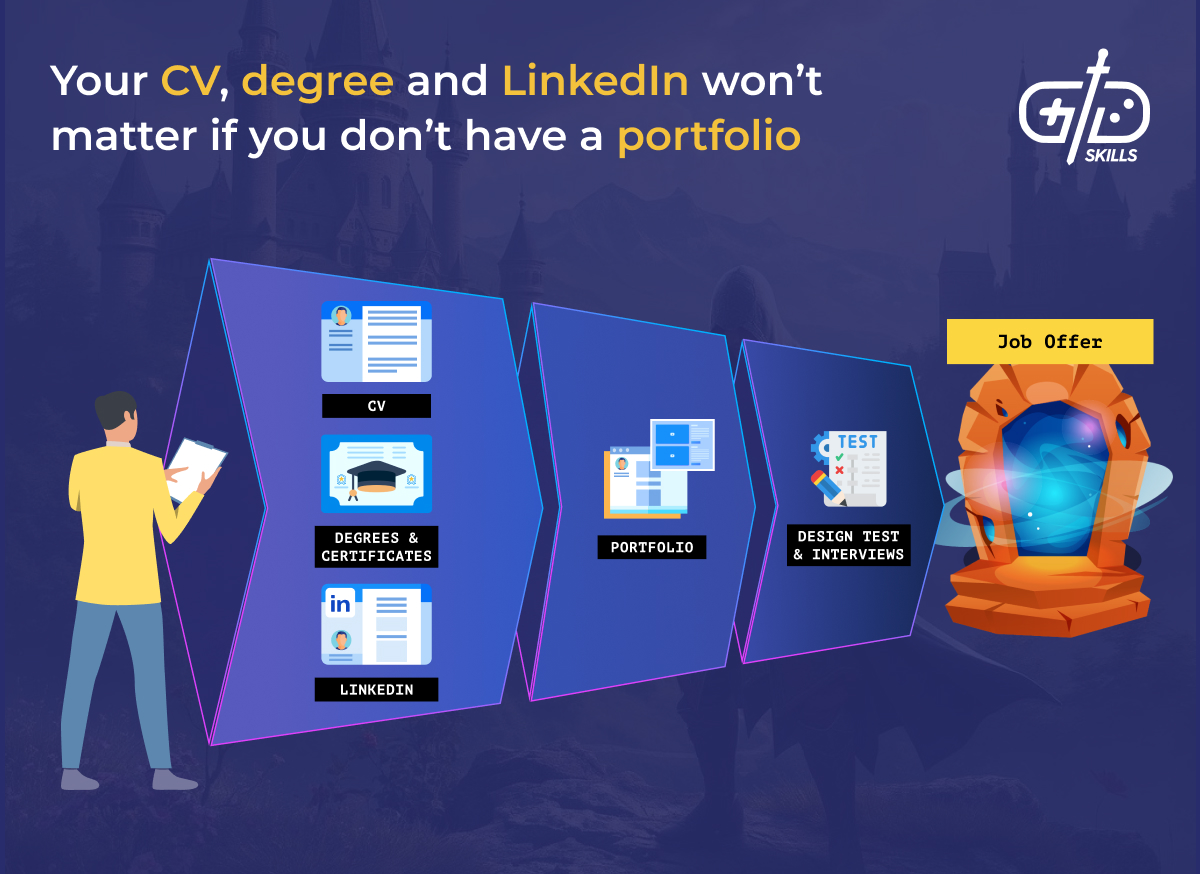

A game design portfolio is a document for presenting your previous work to employers. Presenting your process is such a crucial ingredient for a game design career, but there’s not a lot of specific advice out there for putting it together.

Read on to learn about how to build a portfolio matching your experience level. A starter portfolio gives a summary list of responsibilities from project to project with a description of each one. A next level portfolio lists out every contribution, then describes each in three steps: first give the result of the contribution, the goal behind it, and finally the solution you put in place to get to the result. Each paragraph has a supporting visual that makes understanding the point effortless. A portfolio doesn’t actually need as much detail after that. A designer with lots of industry experience already has the credibility they need.

Learn a step-by-step process for putting this format into action. Start with finding your niche, then implement the steps in the following list.

- Define your game design discipline.

- Structure for game dev recruiters and hiring managers.

- Curate your AAA quality case studies.

- Demonstrate design iteration.

- Showcase gameplay-first evidence.

- Iterate like a live ops team

- Seek feedback for your portfolio.

1. Define your game design discipline

Define your game design discipline by targeting your portfolio to the niche you’re getting into. Many sub-disciplines exist in game design. Portfolios in level design, narrative design, and gameplay/systems design cover most of the content that’s going to appear in a portfolio, so read on to learn more about portfolios in these three disciplines.

A focused portfolio makes sure you’re competing with the right crowd. The set of skills on display in the portfolio puts you in competition with fewer and fewer other designers. A level designer experienced in Unreal has their own niche that attracts employers to them. Put a title under your name that makes clear what subdiscipline you’re aiming at. Keep in mind that not every title exists at every studio, nor does it have the same meaning at every studio. A mission designer at Rockstar is the same as a quest designer at other studios, and a narrative designer does different tasks from company to company.

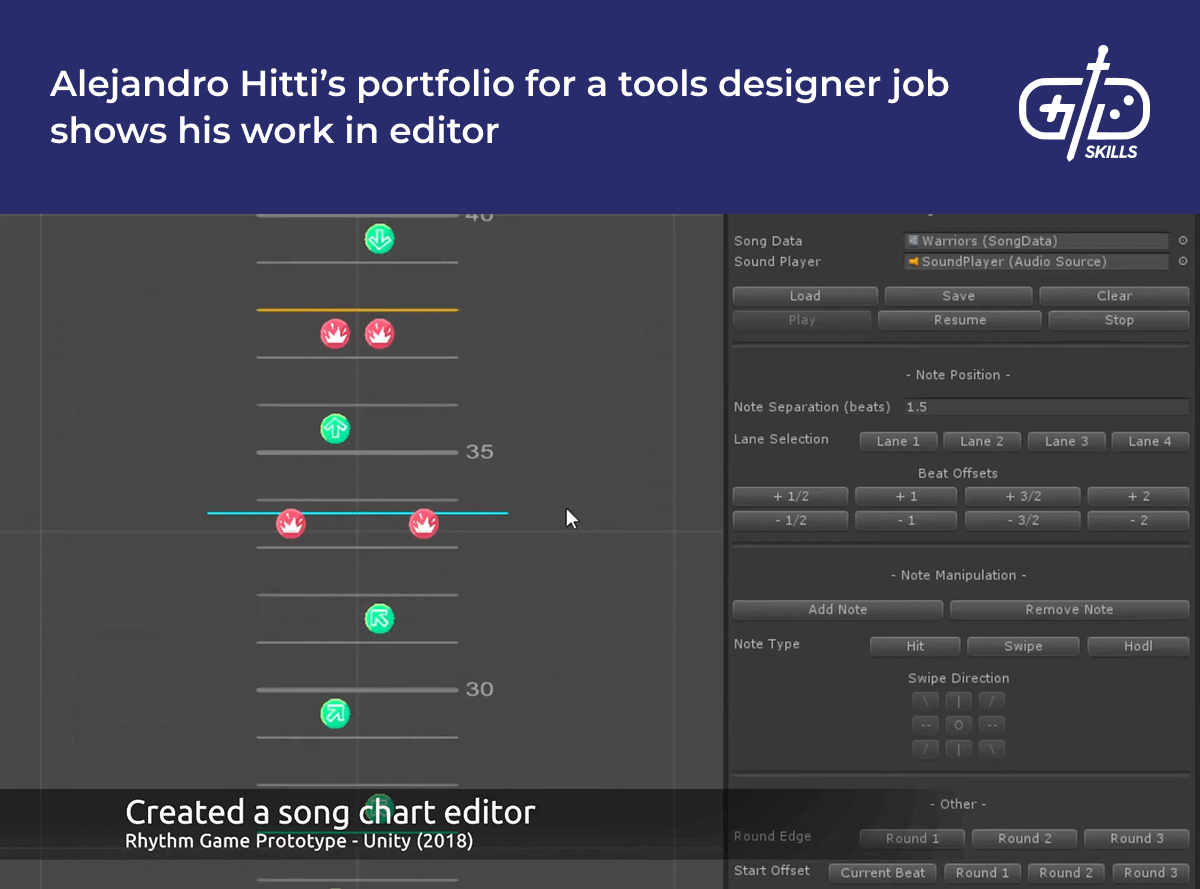

Every game design discipline is different, but that doesn’t mean every portfolio is different. One template is useful for gameplay and systems designers, even though both designers are very distinct. Their portfolios focus on problems solved under the hood, not an apparent level like a level designer. The proof for gameplay and systems consists of gameplay, in-engine screenshots, documentation, reviews, and playtests, to name a few. Following the same general template works for each.

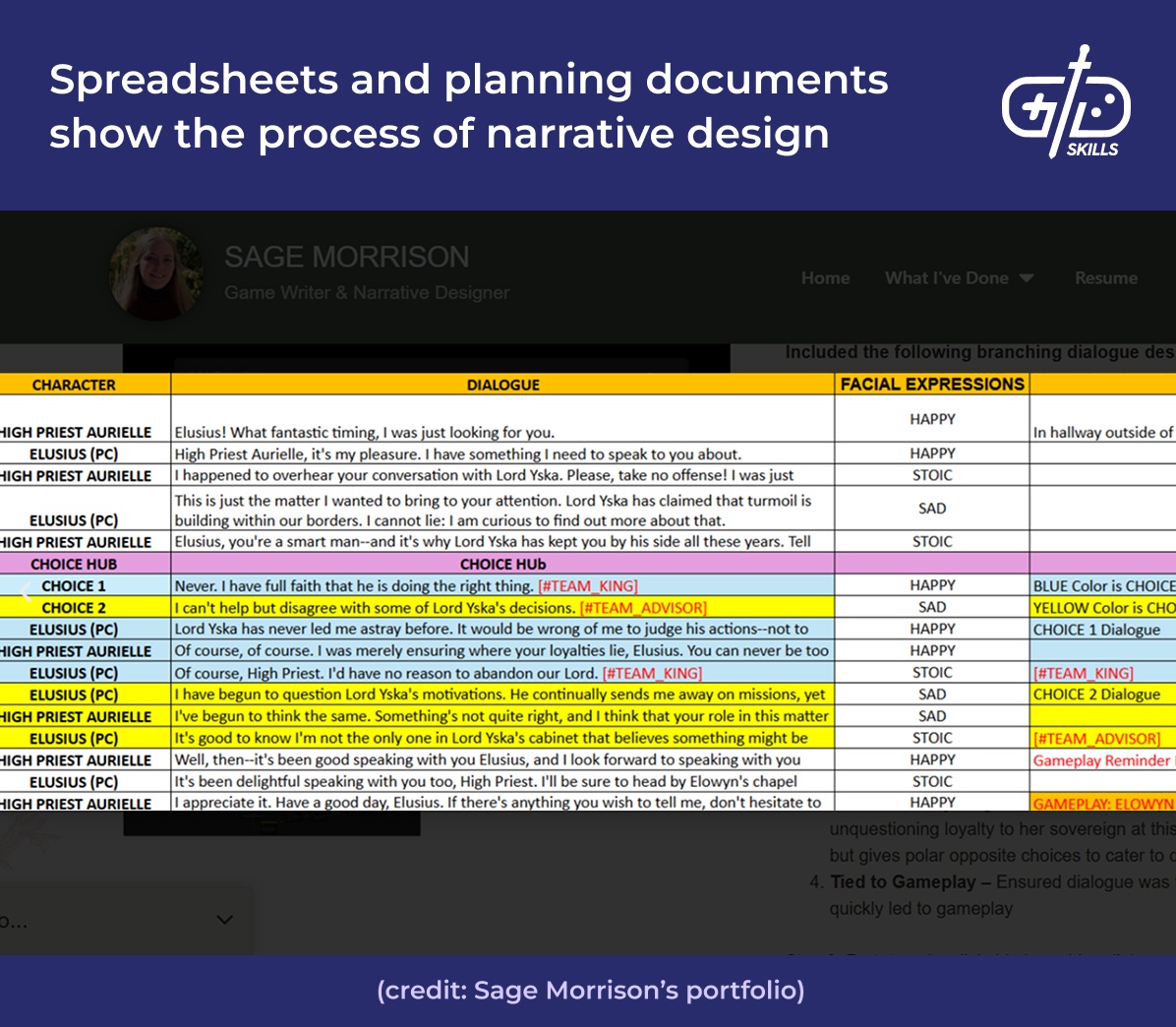

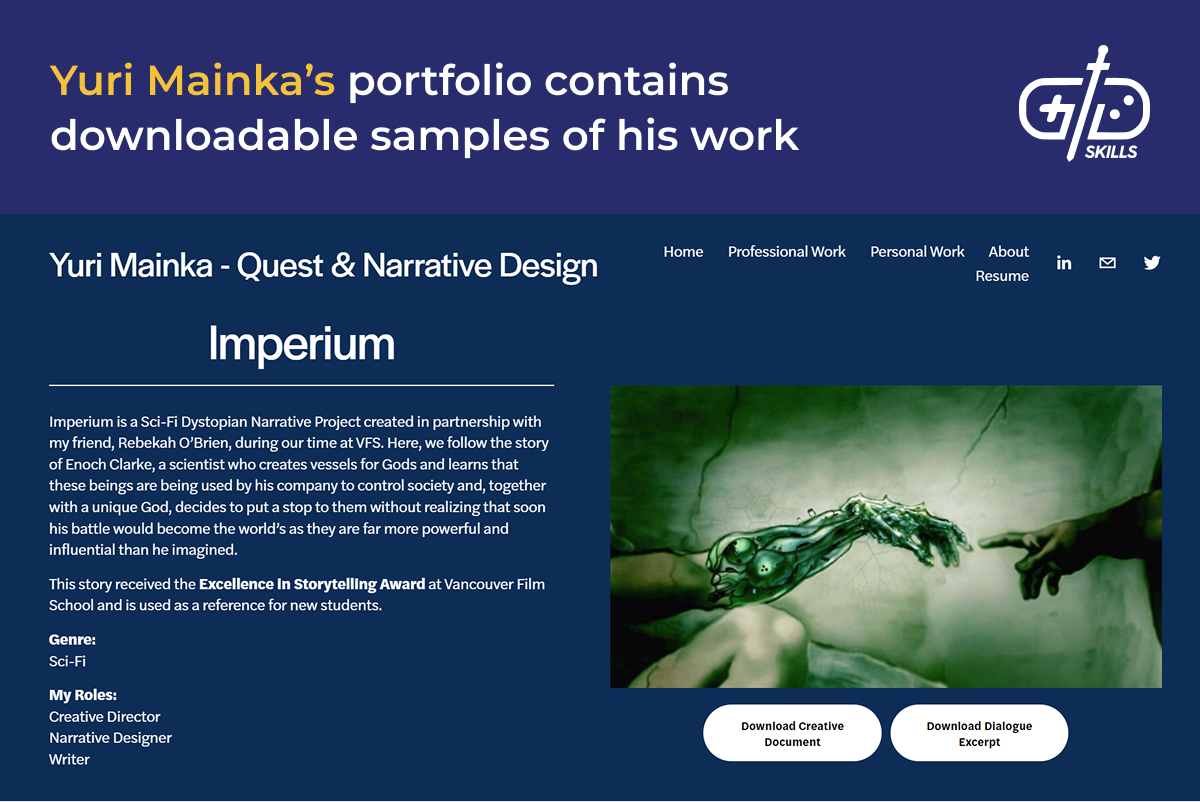

Narrative designers need to demonstrate an ability to write dialogue, barks, quests, and character designs. Finished gameplay isn’t at issue in their portfolios, so they don’t need a finished game to make for a successful portfolio. Writing and documentation make up the supporting evidence in a narrative design portfolio.

Level design falls in the middle, since a finished level is made up of many art and code assets. A finished prototype doesn’t need to look pretty, though, or belong to a finished game to go in a portfolio. A playable level with working gameplay is enough to make for a portfolio piece. Video of that gameplay and player’s reactions to it is proof of a level designer’s competence.

The three portfolio types covered here are gameplay/systems design, level design, and narrative design. They cover a cross-section of portfolio types you’re likely to need. There are lots of other designers and disciplines involved in making games, so follow the advice that’s most applicable to your niche.

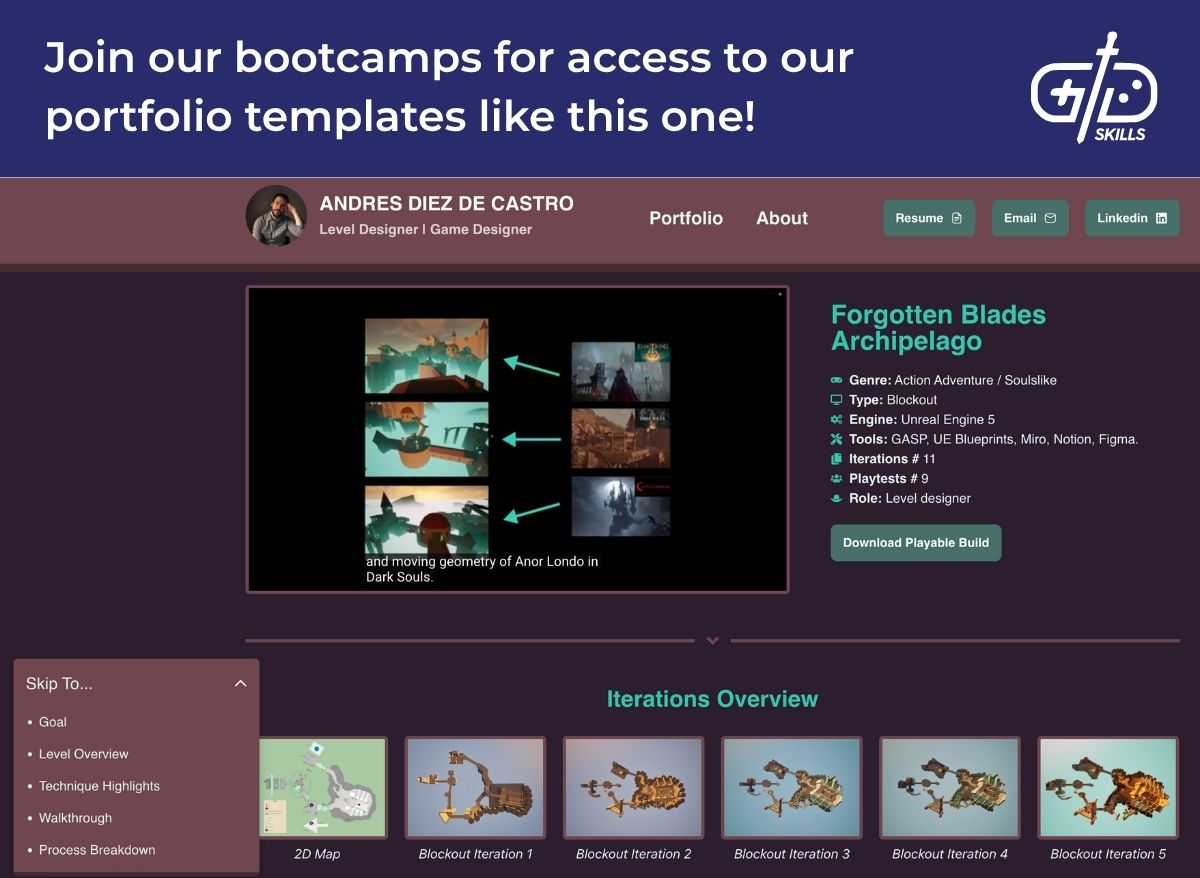

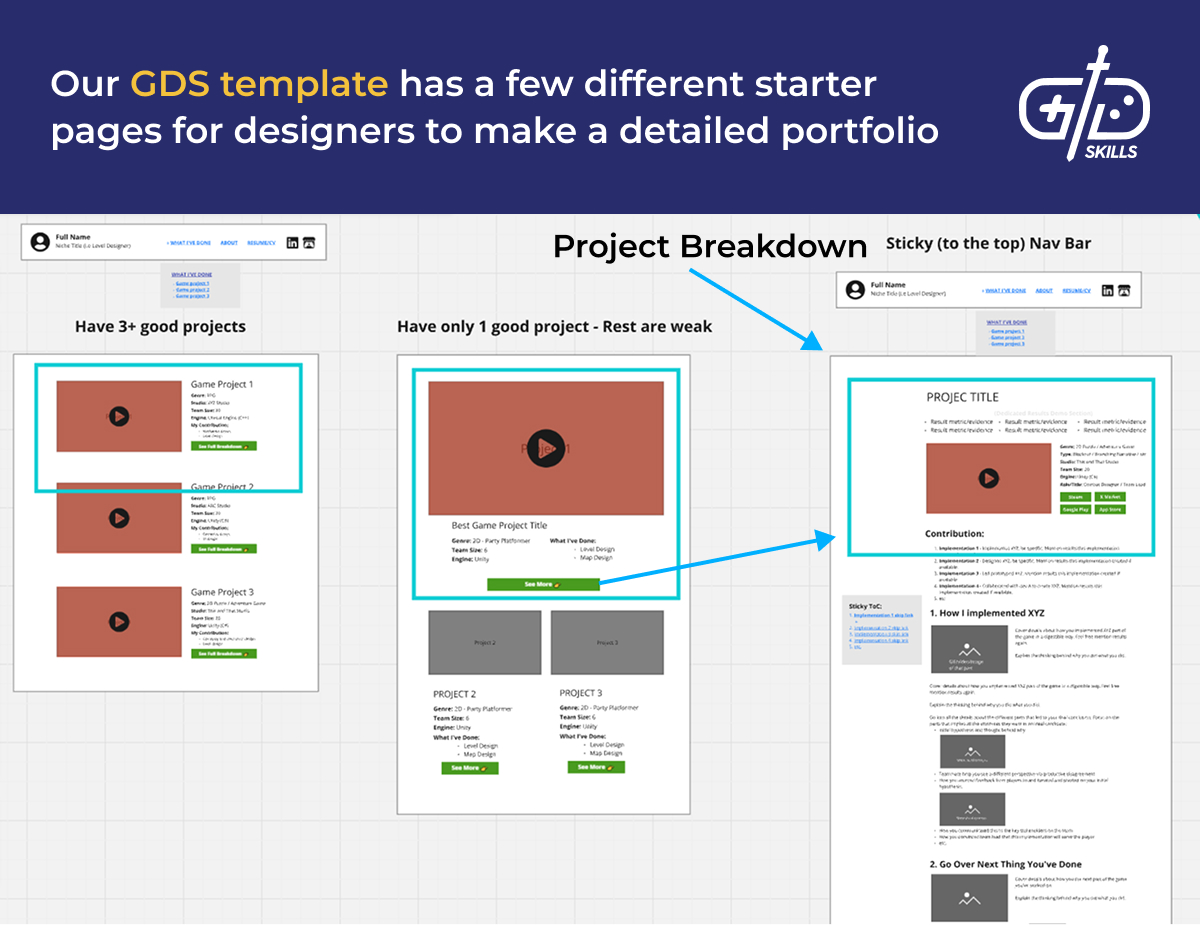

A portfolio doesn’t have to wait for a discipline if you’re just getting started. Submitting an imperfect portfolio and working on it at the same time is better than not submitting applications at all. Our GDS template offers a place for new designers to start. There’s a template for those who have completed only a few projects and want to showcase their best work.

A portfolio doesn’t have to wait for a discipline if you’re just getting started. Submitting an imperfect portfolio and working on it at the same time is better than not submitting applications at all. Our GDS template offers a place for new designers to start. There’s a template for those who have completed only a few projects and want to showcase their best work.

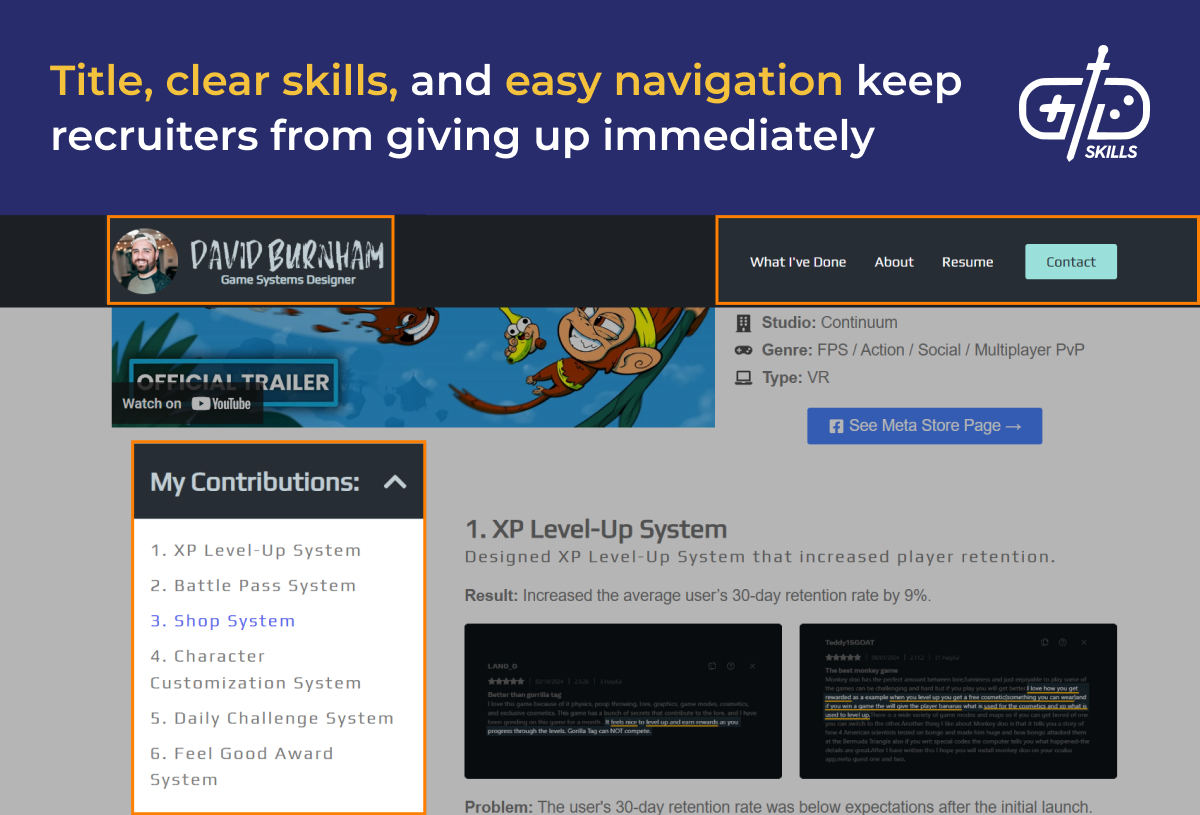

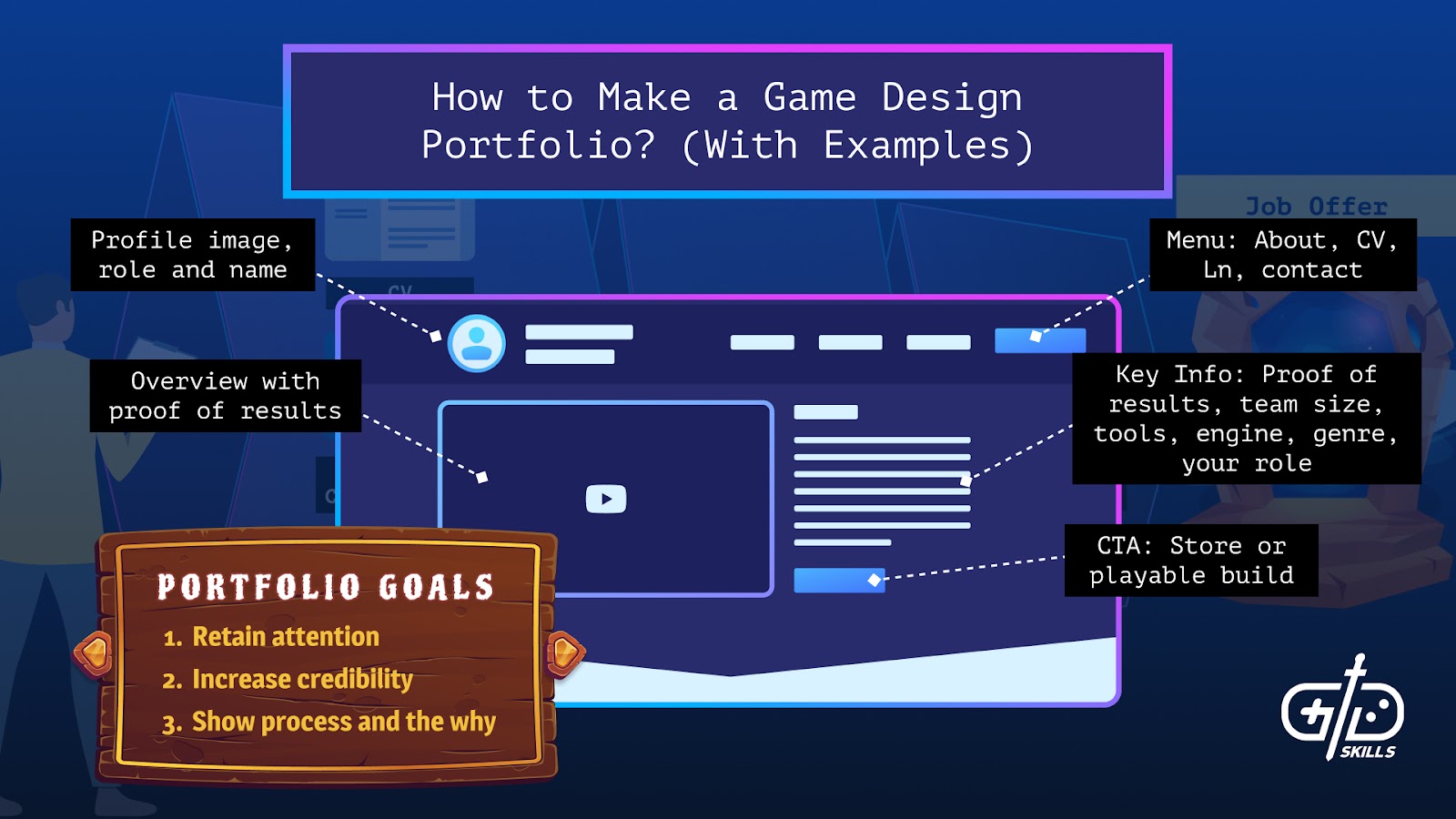

2. Structure for game dev recruiters and hiring managers

Structure the portfolio for game dev recruiters and hiring managers. Recruiters aren’t experts in game design, so they’re not going to understand all the nuances. Hiring managers know more about game design and expect to see more detailed explanations of your accomplishments. Include the most important information up top, summarizing contributions that make it clear why you’re valuable to the hiring team. A portfolio isn’t a resume, but a way to show skills a resume doesn’t. Clear headings, short paragraphs, and well-formatted text make the portfolio easy to understand.

A recruiter takes a first pass before the portfolio goes on to the hiring manager. A recruiter only glances at the portfolio, so the most relevant information needs to come up front. The situation isn’t ideal, but recruiters look at potentially hundreds of portfolios. A recruiter scanning ought to be able to see your experience at a glance and whether you hit all the keywords the ad is looking for.

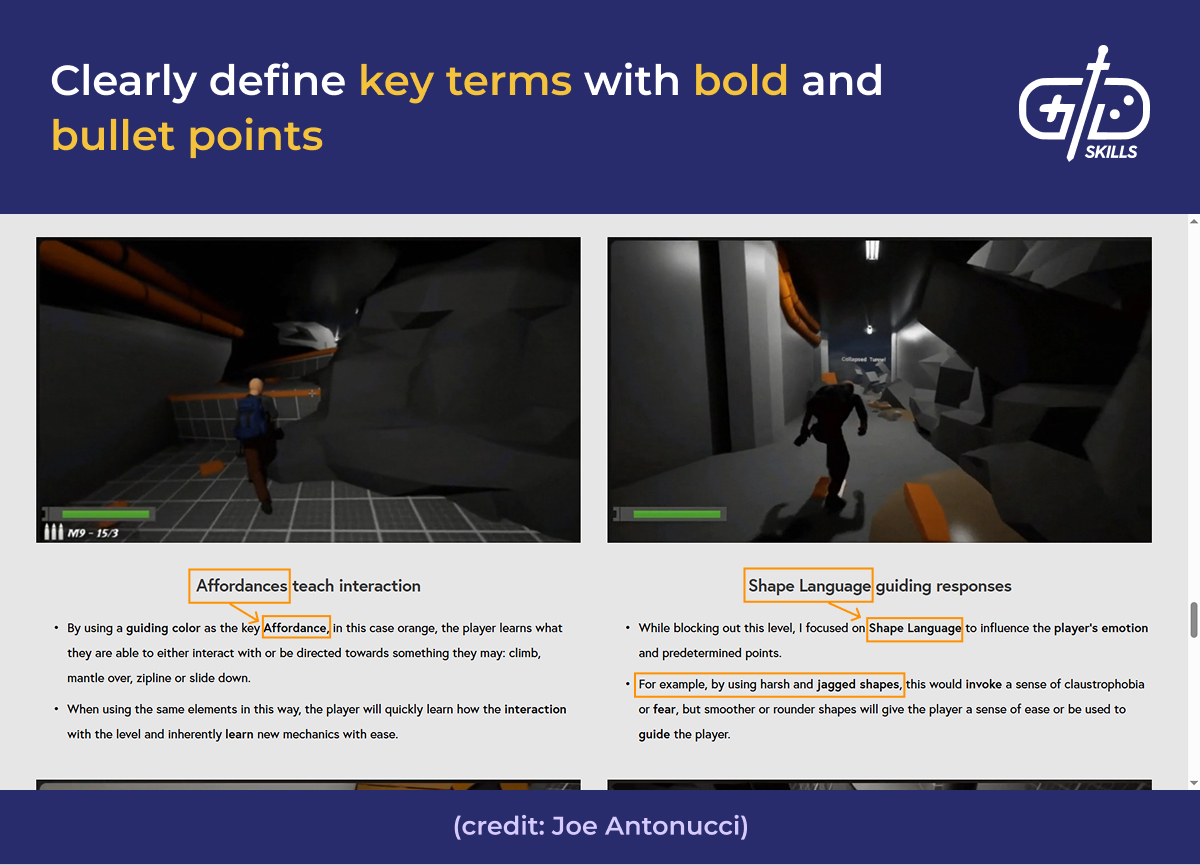

Keep headings clear and easy to read. Game design jargon like “affordances” is understandable and worth using when the audience is only other game devs, but recruiters aren’t going to be as knowledgeable. Use that kind of jargon only when necessary and define it when you do. A term in the heading needs a bolded definition in the body paragraph so a skimming reader easily finds the definition.

Make a deep-dive intro video that draws the viewer into the portfolio. A short video is much more accessible than the full portfolio. Some designers include trailers, but an overview of the portfolio is an even more effective use of that space. The first thing a reader sees is the opening video, so putting a summary of the rest of the portfolio there helps ease them in. It gives them context and prepares them to understand the rest of the work in the portfolio.

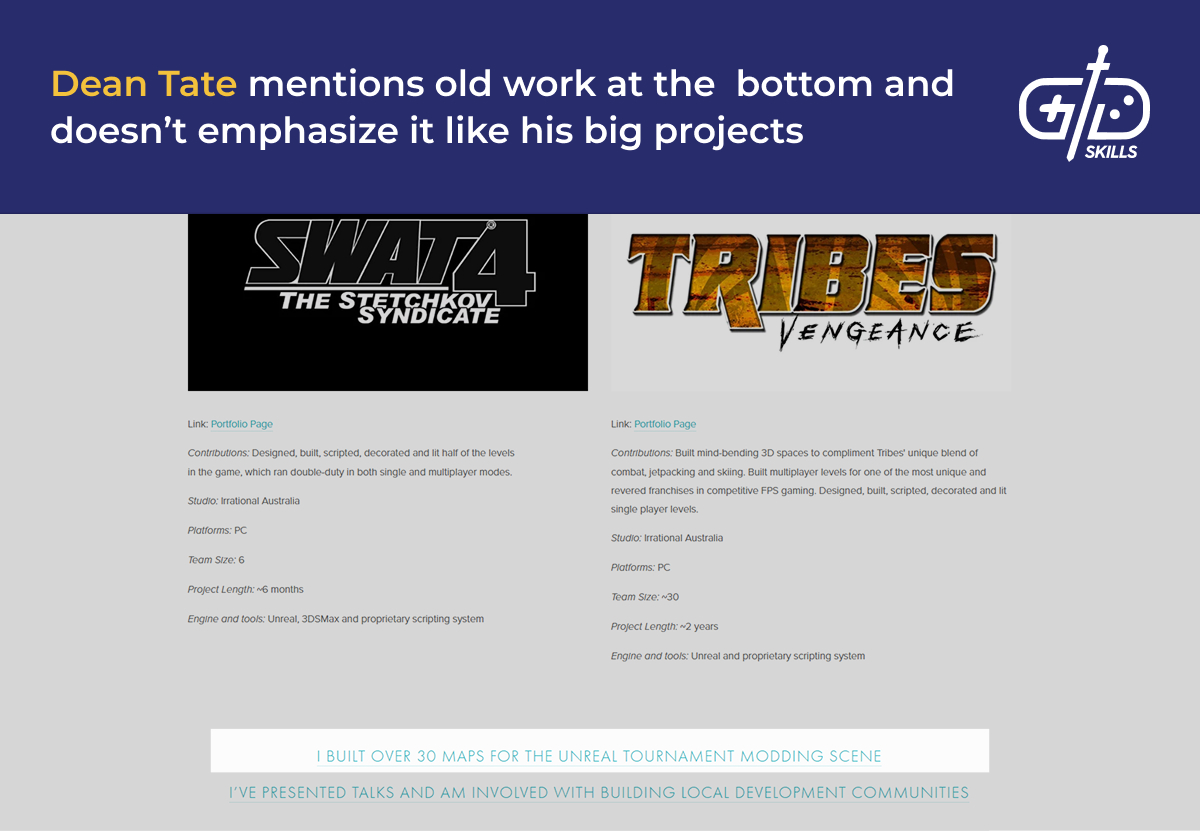

The goal of a portfolio is to get to the next stage of the hiring process; it’s not a resume. A resume is a list of claims, and the portfolio is the proof. The portfolio isn’t a retreading of what’s in the resume. Only include the best and most representative work. Stick to mostly finished projects, and more recent projects. Older projects show an older version of your skill level, not the current one.

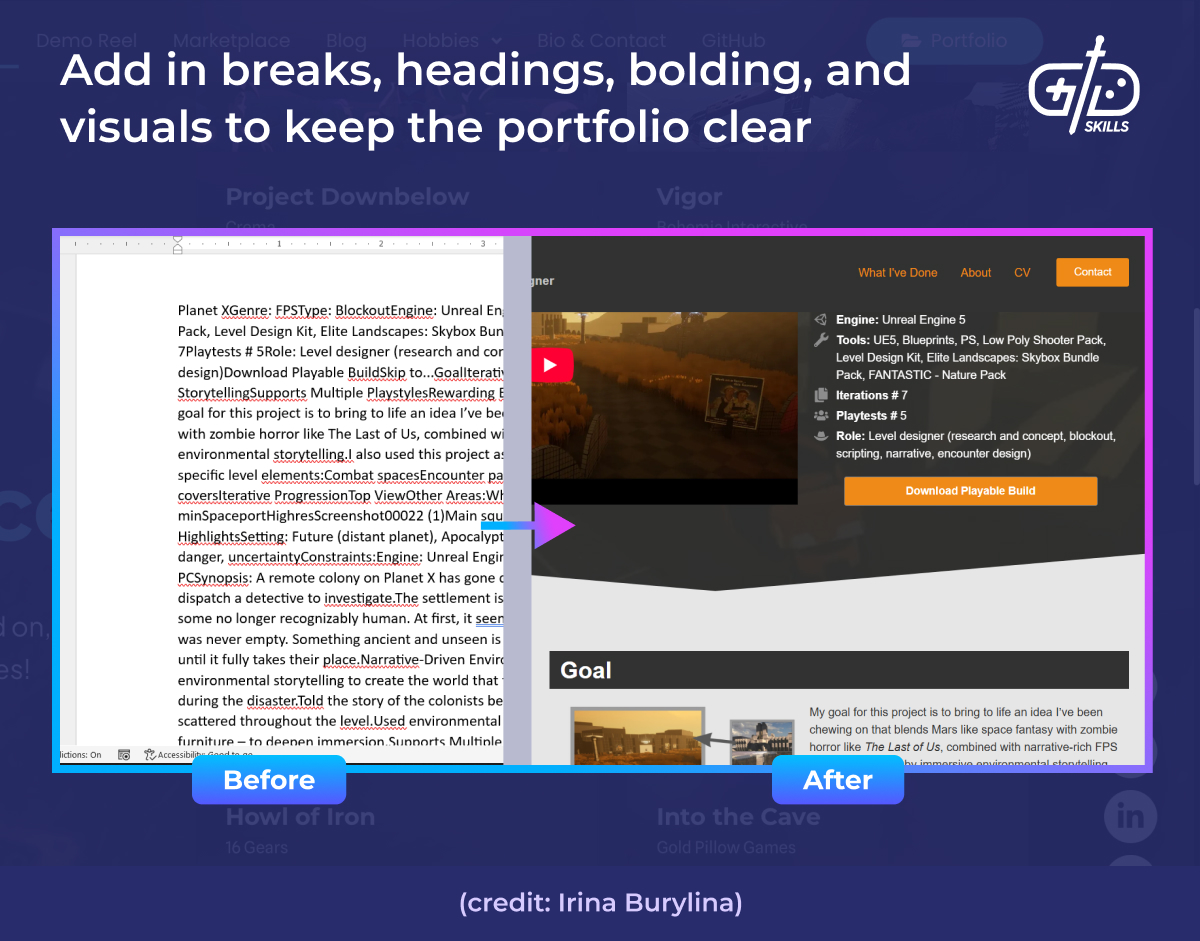

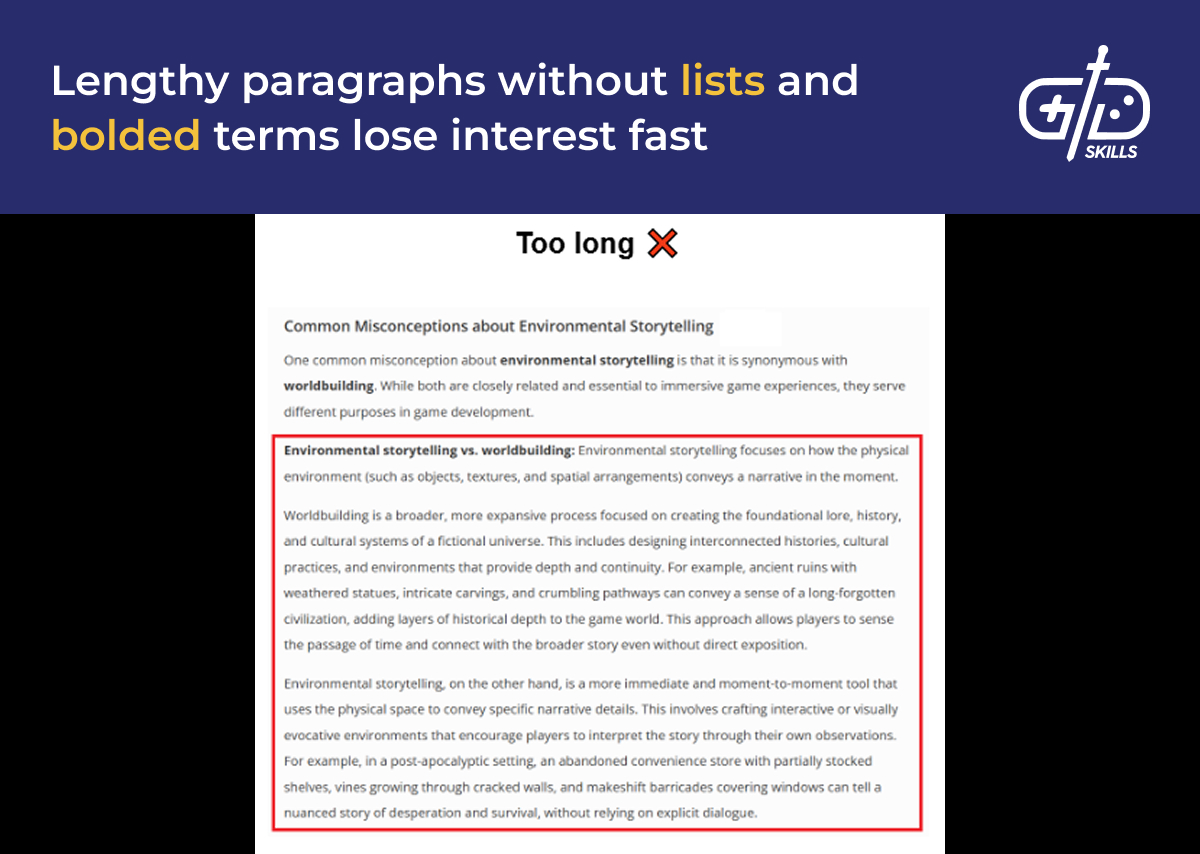

A portfolio’s formatting takes a good portfolio and makes it a great one. Write the portfolio’s text like a copy-writer. How you present your information makes a load of difference on how clear it reads. Break down text into digestible, simple bits. Each section, each project, each set of connected ideas, each set of bullet points starts with a heading. A skimmer has a clear idea of what they’re coming to each section for.

Each paragraph in a section ought to be as short as possible; the goal isn’t to write a college essay. Keep paragraphs to about three lines. Even within paragraphs, use bold and italics to call attention to important terms and phrases so a reader has a vague idea of what a paragraph covers and where to look for more information on a topic.

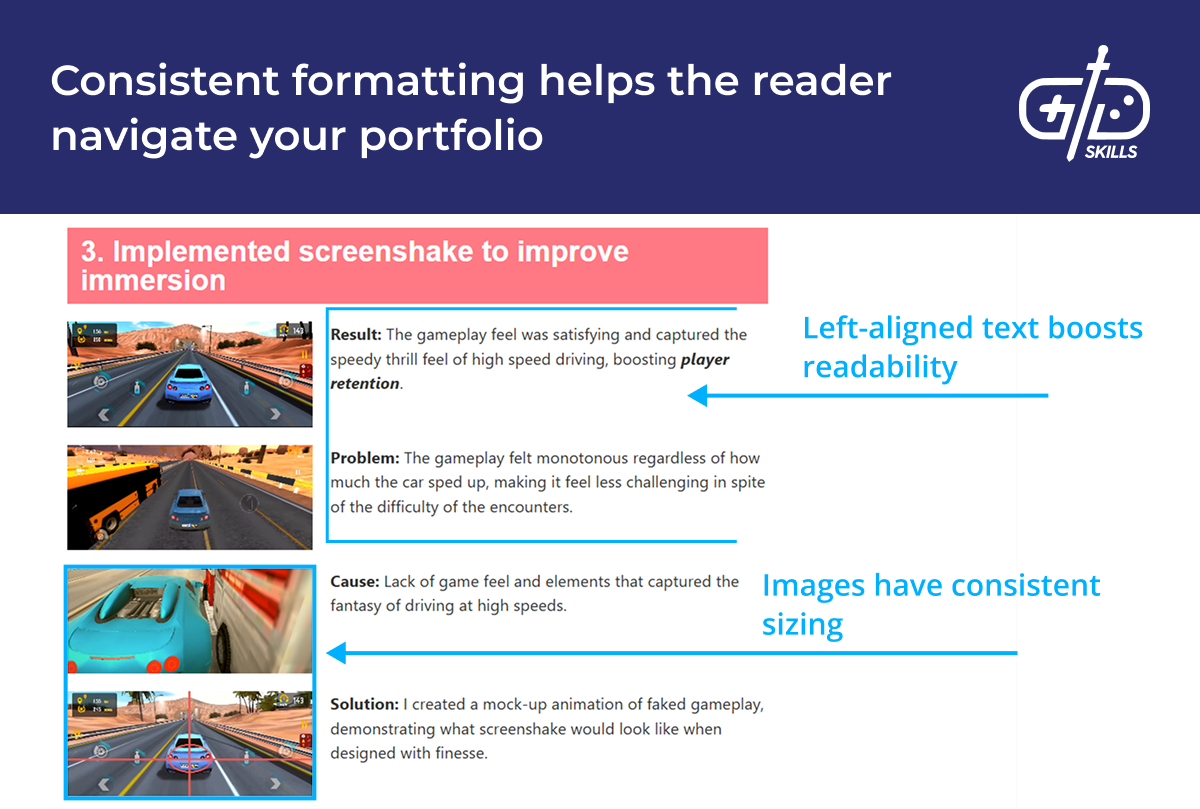

Consistent formatting makes the portfolio as easy to navigate as possible. I align all text left so readers start each line from the same spot. A portfolio is hard to read when each line starts at a different spot like in center or right justified text. Consistent image sizes also help readers approach your portfolio. They create a consistent flow to the body so readers clearly see where each section starts and ends.

Make understanding images as easy as possible. Embed images side-by-side with the text to make it clear what you’re explaining. Editing images helps make sure readers focus on the right part when they scan back and forth between text and images. Add arrows and highlight areas on them to guide the reader’s attention.

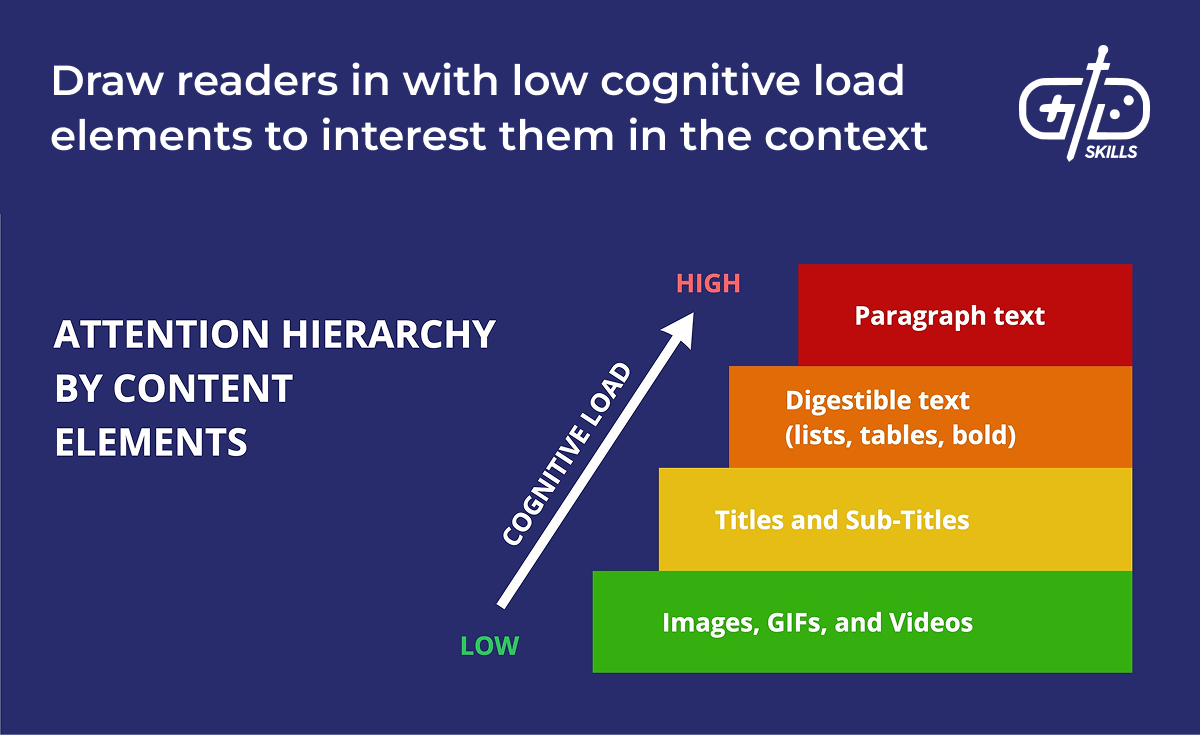

Readers on a time crunch are going to skim through the portfolio. A good portfolio guides the reader to the most important information. Headings, images, bolded text, and bulleted lists pre-digest the information. Readers spot formatted text and images first, so the most crucial information goes there.

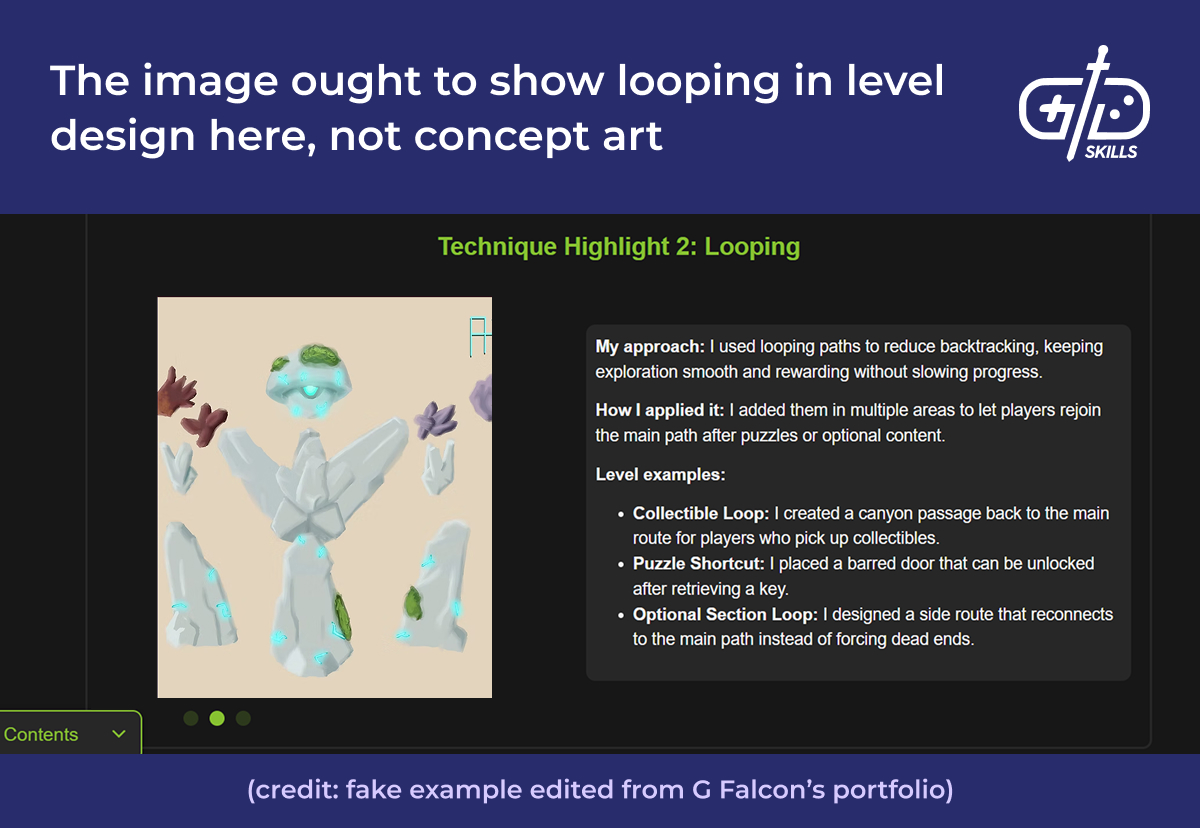

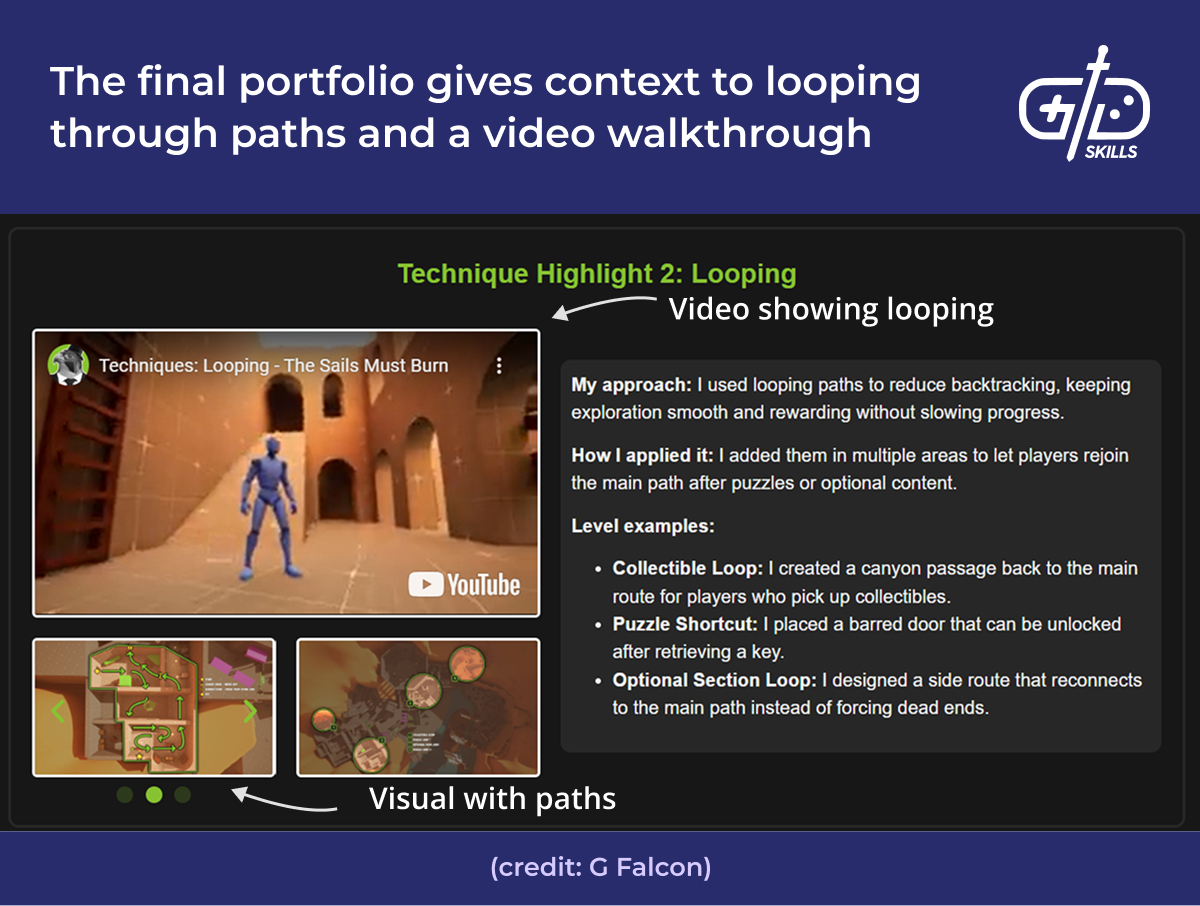

Visuals for the sake of visuals alone harms the readability of the portfolio. An image of gameplay to add flavor or just break up the text is better than a wall of words but isn’t enough. The images have the potential to add context the writing isn’t able to. A section discussing how effective your use of looping was doesn’t make sense without a visual of looping in the level, for example.

A more effective portfolio puts a video or image showing the technique in action. The real visual from G. Falcon’s portfolio gives context to the text. “Looping” is an approach to the layout that avoids backtracking. Paths that branch out from the main path also lead back to it. G Falcon shows sections of the level with a video walkthrough. Their images highlight the sections from above, showing how they connect and where they’re laid out compared to each other.

3. Curate AAA-quality case studies

Curate your game projects as case studies to make sure your contributions to the project are clear. Completed projects show an ability to work with a team and execute on a vision, so including information about each game and what went into it is crucial for communicating your skillset. Gameplay/systems designers, level designers, and narrative designers each format their case studies differently to highlight the unique skills involved.

As comprehensive as a portfolio may be, there’s a limited pool of attention for everything on its site. Keep to a few projects and start each project with the most relevant information. One reason is that the recruiter reviewing it is busy. They need to see the main points at a glance, and an overwhelming number of skills, tools, student projects, and work experiences makes it difficult to parse.

Another reason to carefully include and exclude case studies is to focus them for the job. Say there’s a designer looking for a level design position. Their portfolio lists work as a level designer and a systems designer who also created enemies at the same time for 15 different projects. A recruiter isn’t sure what the applicant’s strengths are when their portfolio covers so much unrelated information. Less is more here.

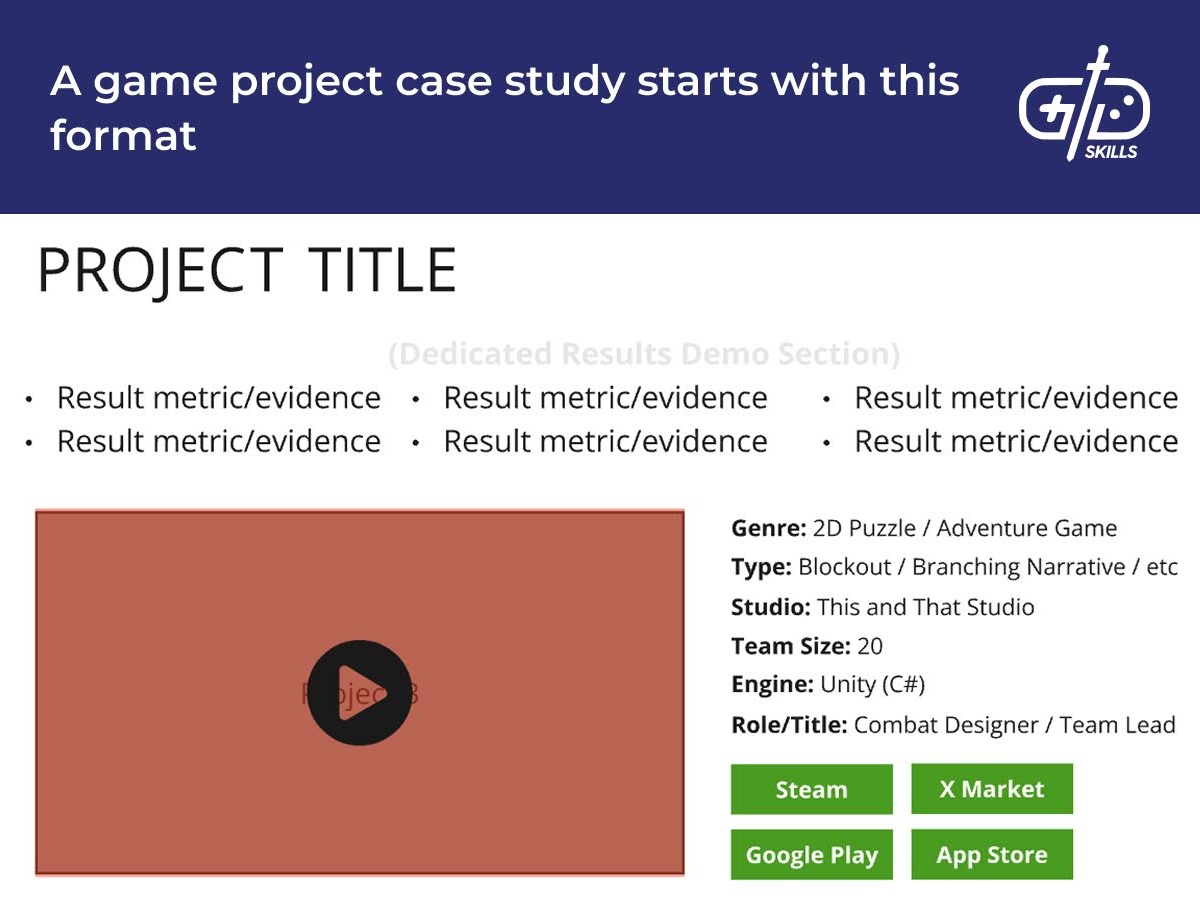

Each case study in a portfolio communicates basic information about the project and responsibilities. The goal is to communicate at a glance what the significance of the project is: what impact you had, what roles, and what tools you used. Include your title, the projects you’ve worked on, and contributions up front. List the studio and team size underneath the description of the project if the project is a commercial one.

Personal projects are good to include if they’re finished. Don’t mention whether a project was made in school or in a class, as insiders tend to look down on work produced in an academic setting. Feel free to mention that feedback came from the instructor without mentioning they were a teacher. Including the number of iterations, playtests, and time to completion also shows an ability to polish and stay on track even in personal projects, which is crucial for a marketable portfolio.

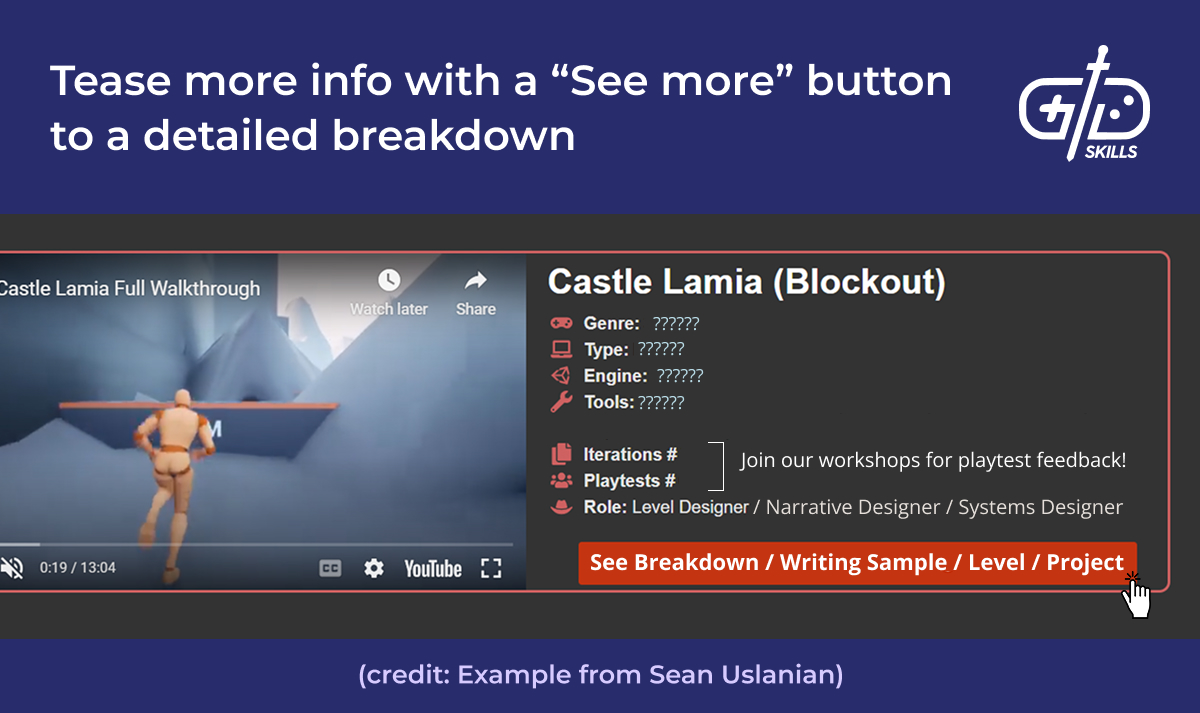

Completed personal and professional projects link to a more detailed breakdown from the general summary. A glance at the main page shows the games and contributions the designer has worked on. The design team hiring for the position has the option to click for a more in-depth deep dive with a list of responsibilities, contributions, and decisions made during the project.

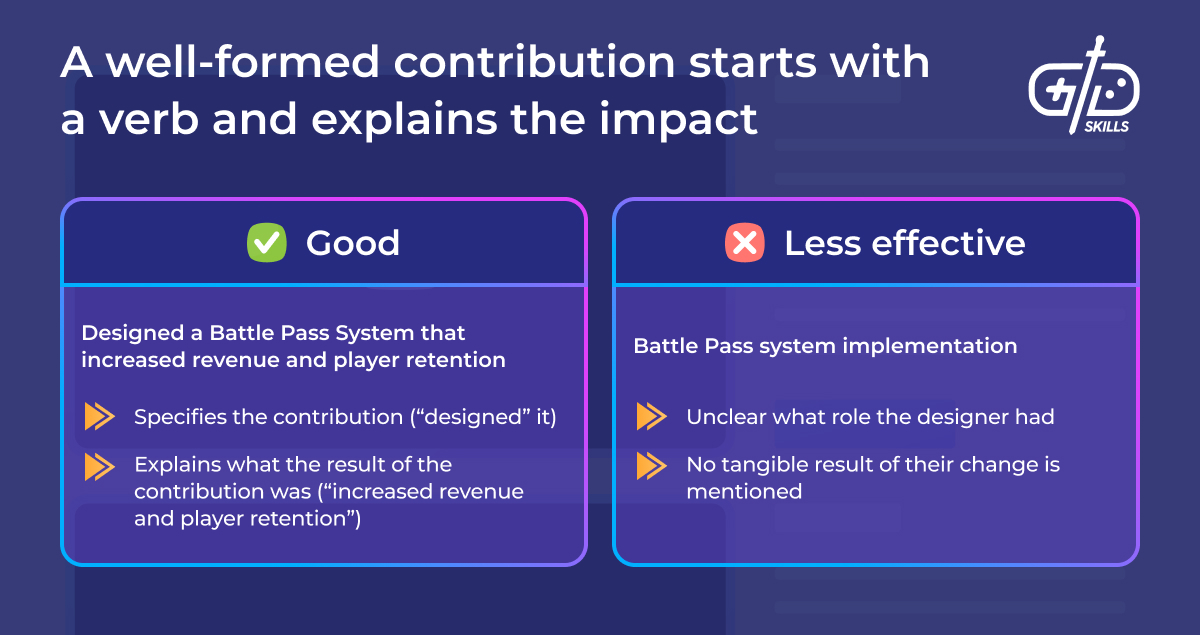

The next section enumerates the contributions to the project. Each contribution is composed of a verb, what you worked on, and the results of it. All three components are crucial to demonstrating a skill. The best kind gives a direct, measurable result for each contribution.

The format of the rest of the deep dive depends on the type of portfolio. A level designer includes more images of the level in progress and videos of gameplay.A narrative designer includes writing samples showing they’re able to write for a non-linear experience. A gameplay/systems designer includes diagrams, pictures, GIFs, and gameplay that shows their problem-solving process.

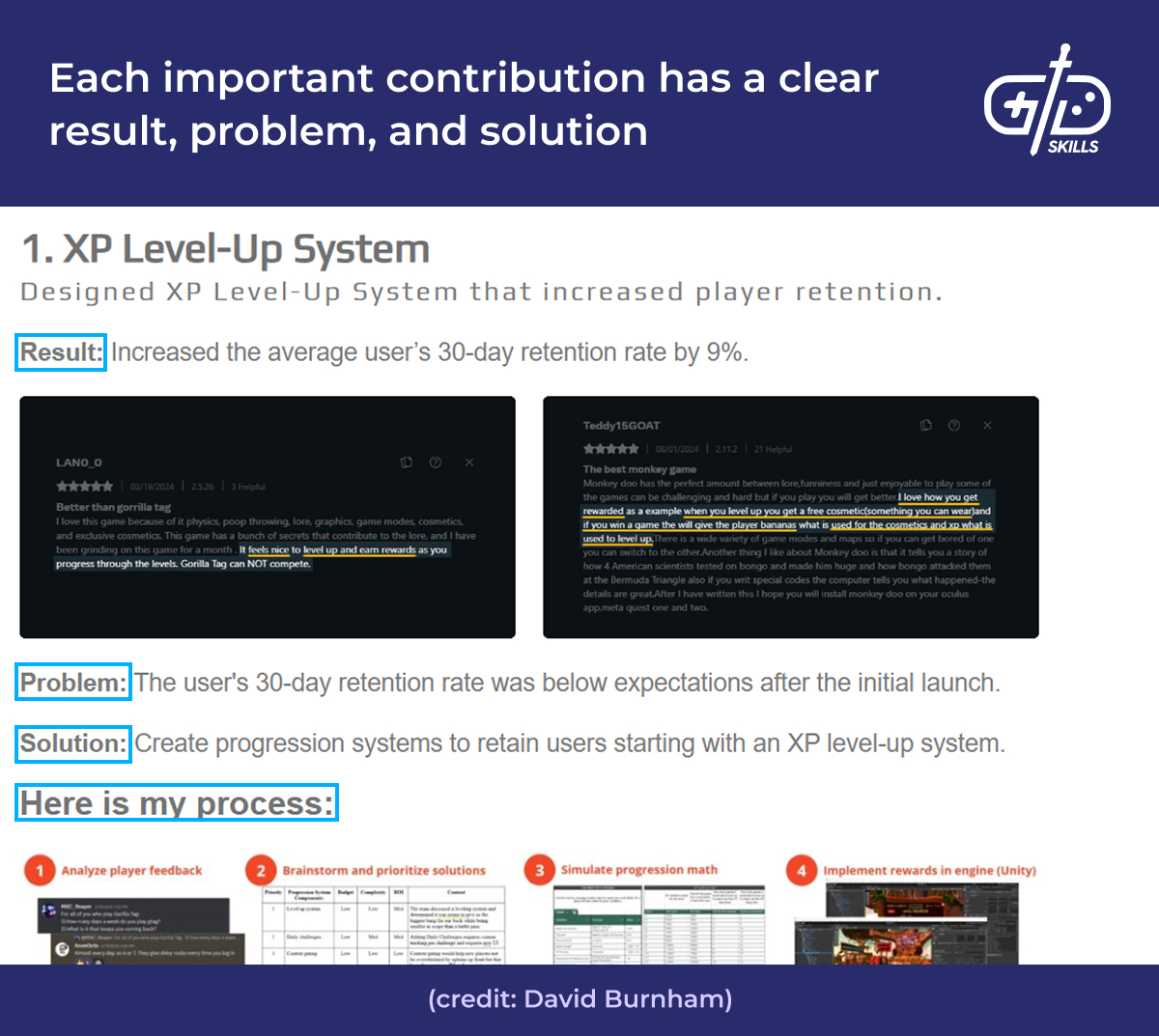

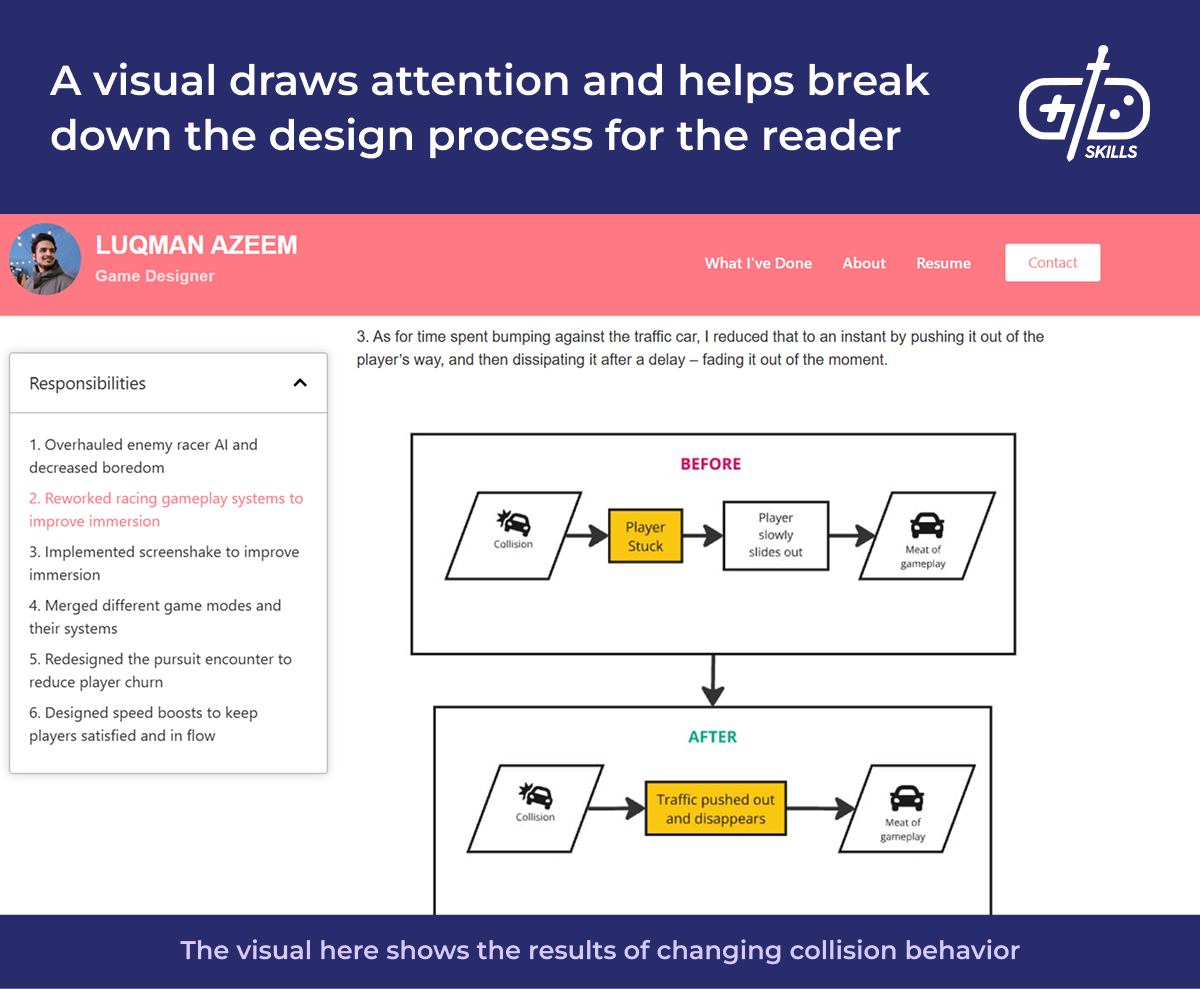

A gameplay/systems portfolio redefines each contribution with a hook via problem/solution/result, then dives into the process via visuals. A consistent breakdown of each contribution makes the portfolio easy to navigate. The format also puts the most important information up front. Each contribution is given in the order Result, Problem, Solution because the result sounds the most impressive.

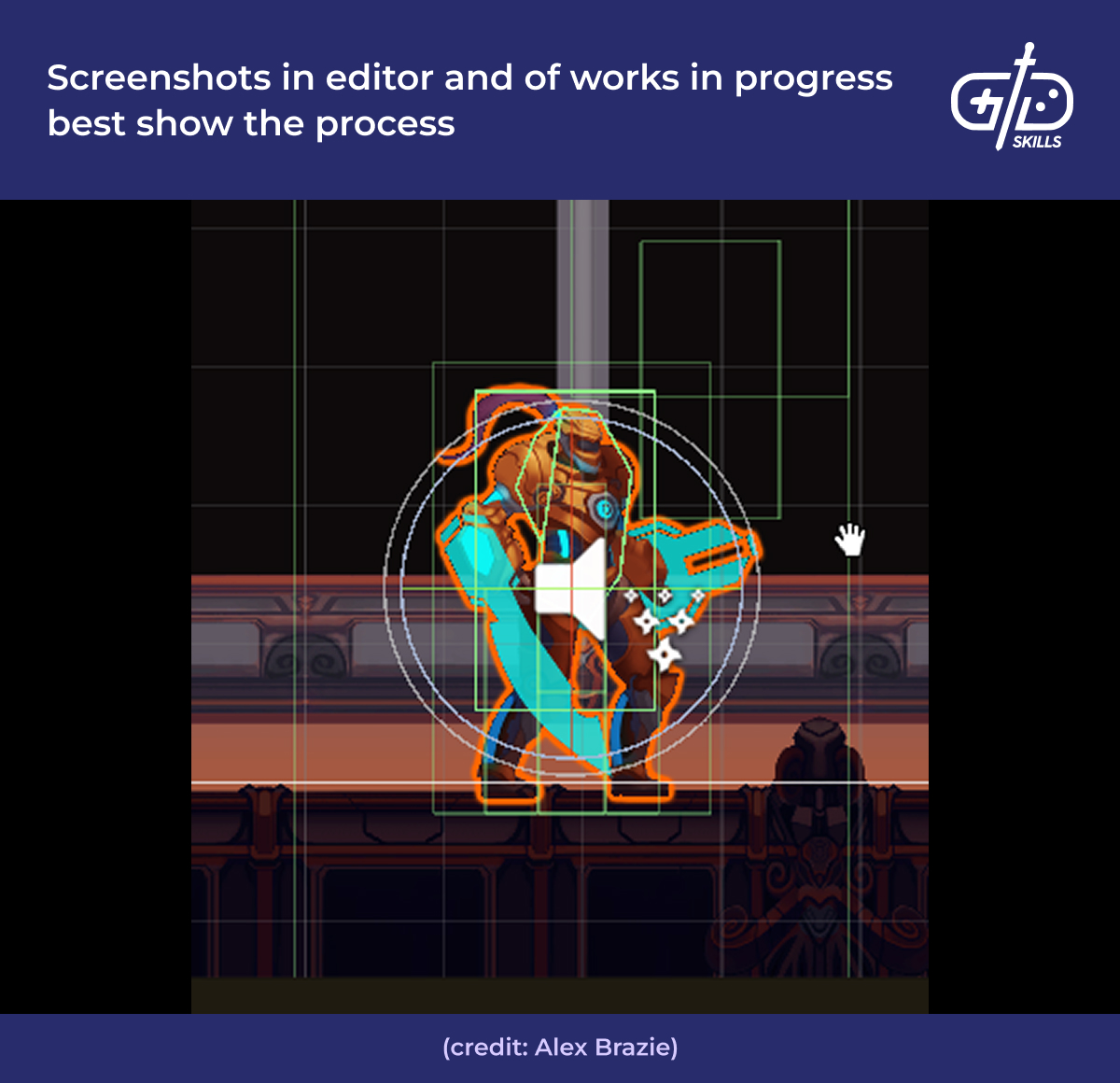

Dive into each contribution with an explanation of the process, and support each paragraph in your explanation with a visual. A visual is often a screenshot, GIF, or video of gameplay. Not every contribution has gameplay footage associated with it, though, so diagrams, in-engine screenshots, and documentation are also effective supporting evidence. Mock up a diagram in Miro or other flowchart software if you don’t have access to documentation.

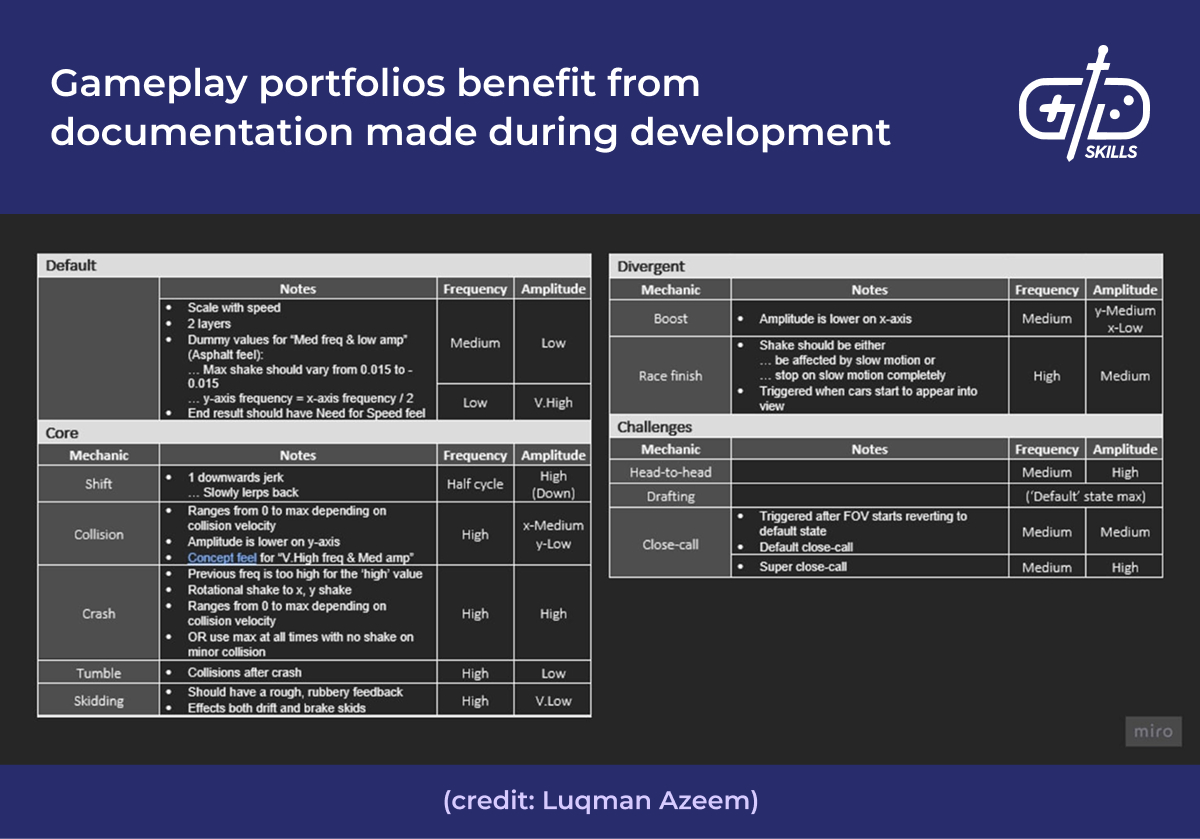

Break down each contribution step by step. I break down many of my larger contributions into phases, each with multiple paragraphs and images describing the process. Phases are like subheadings within each contribution. My section on screenshake in Racing Ferocity, for example, labels each phase with a heading. The first heading, “Timeline prototype to get team buy-in”, leads into the second heading “Documentation, implementation, iteration.” Each heading is short and tells the reader exactly what parts of the process they’ll learn about.

Level design projects follow a different format. The reader starts with the goal for the level, what frameworks guided their decision-making process, and any influences. The last is especially important for a budding designer’s projects, as a studio is hiring for an ability to match their style, not a completely unique style. A list of major level beats and techniques follows before diving into the process. Each level beat ought to come with a video explaining how you came to make the decisions you did.

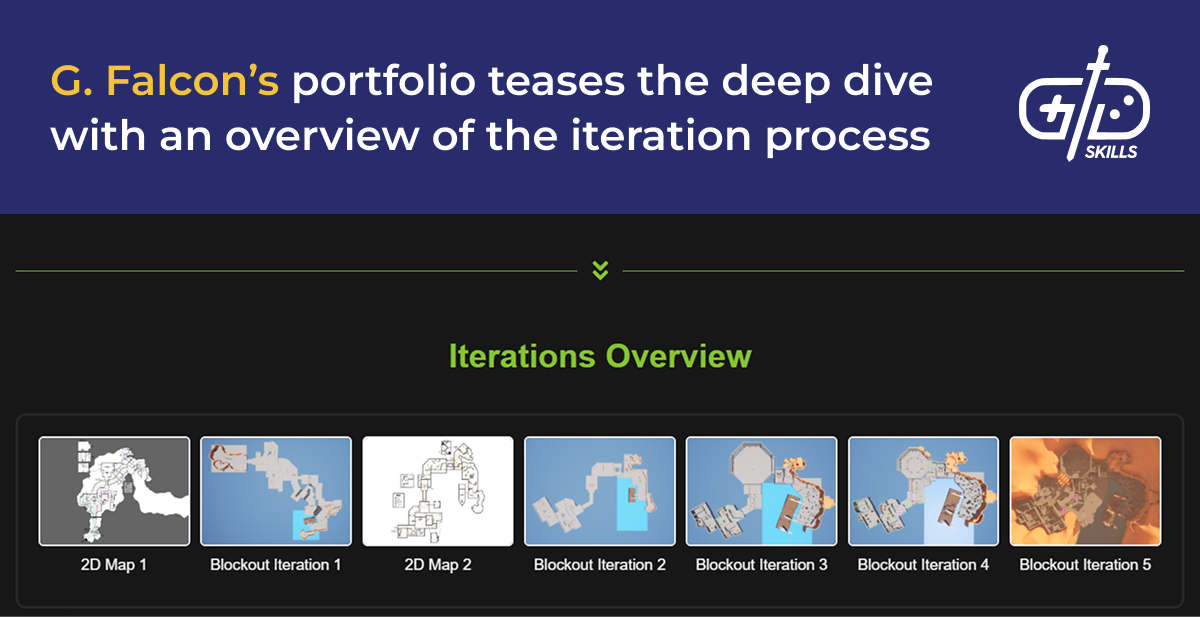

Each section of a level design portfolio shows the process of iteration to the reader. Top-down views of the level and side-by-side comparisons give the reader a clear idea of the effect the design process had on the project. “Before and after” views are accomplished in a few ways. An image gallery that switches between images every few seconds uses space more efficiently than a list. A timelapse in GIF or video form also gives extra context for the changes you’re discussing.

Start the narrative design portfolio with a preview of your narrative work. The kinds of skills to show off at the start of the portfolio include dialogue writing, creating barks, writing voiceover instructions, character design, and storyboarding. Each section of the portfolio must demonstrate some skill, otherwise it’s extra unnecessary information.

List each skill in a narrative design portfolio in order from most to least common. The principle is the same as with resumes and the other portfolios: information higher up on the list and more prominently featured is going to get the most attention. Portfolios using our template start with the writing and documentation first. Character, area, and world design call for detailed descriptions too but they aren’t as important, so they go farther down.

4. Demonstrate design iteration

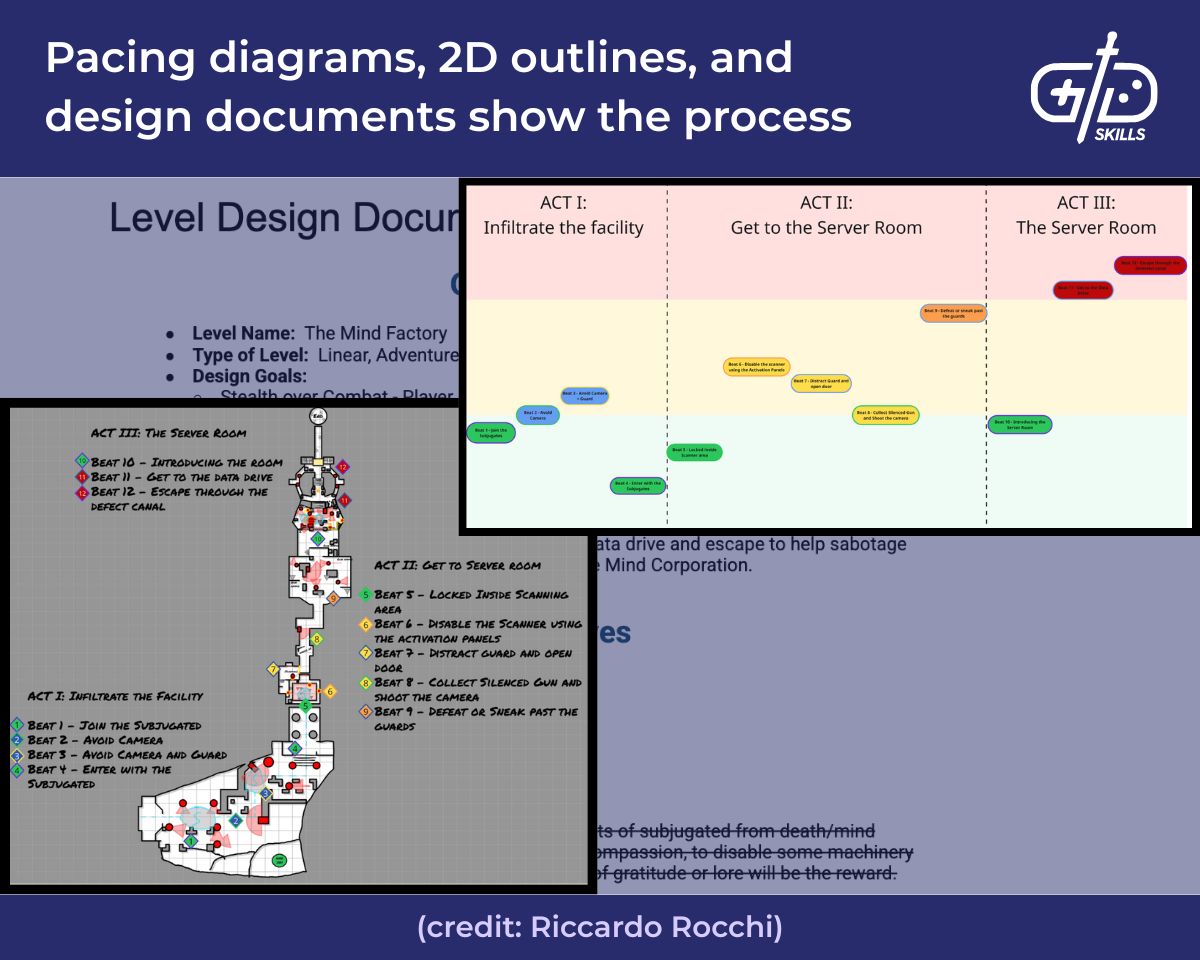

Demonstrate design iteration, not just the end results. Game design is a set of problem solving skills, so showing the how is more important than the what. Challenges during the design process, ideas, diagrams, and screenshots of work in progress show designers the skills that are listed in the resume.

Include behind-the-scenes work to show how you solve problems. An artist sells their artwork, which is easy to show, but a game designer sells a thought process. The thought process is going to look different depending on the type of designer you are.

Level designers show drawings, mockups, beat charts, and editor screenshots. The presentation matters too. A GIF that shows a progression of a blockout from stage-to-stage is better than a single screenshot of the end result. The process feels much more dramatic when unfinished and finished work appear side by side.

Narrative designers show more specific skills than a level or gameplay designer. They work with different tools than other game designers first of all. They use planning tools like word processors, Miro, Arcweave, and Twine. Using these tools shows you’re familiar with prototyping interactive experiences, not just writing for games. Documentation and playable samples make up the parts of a narrative design portfolio, then. Prototypes, spreadsheets with information about characters, lines of dialogue, and VO directions show they’re able to work with a team.

Gameplay and systems designers include evidence of their work during development. Spreadsheets, flowcharts, WIP screenshots, and documentation are tangible evidence of an ability to communicate with the team and show a thought process. Create fresh diagrams with Miro if you don’t have access to the documentation used during development.

An example from my work on Racing Ferocity is the mockup I used to sell camera shake to the team. Camera shake was not a priority in Racing Ferocity when I joined on. I knew it had the potential to add a lot to the gameplay, so I created some fake gameplay to show them what it looks like. The difference in game feel appeared huge, and the feature immediately became a priority. These types of stories are solid inclusions for a gameplay portfolio. The images show how big of a difference the feature made, and also demonstrated that I’m able to get buy-in from the team.

5. Showcase gameplay-first evidence

Showcase gameplay-first evidence that makes your contributions clear. In-progress work is helpful, but finished gameplay shows how the process translates into a workable game. Use pictures, GIFs, videos, and screenshots to show potential employers the results of your work.

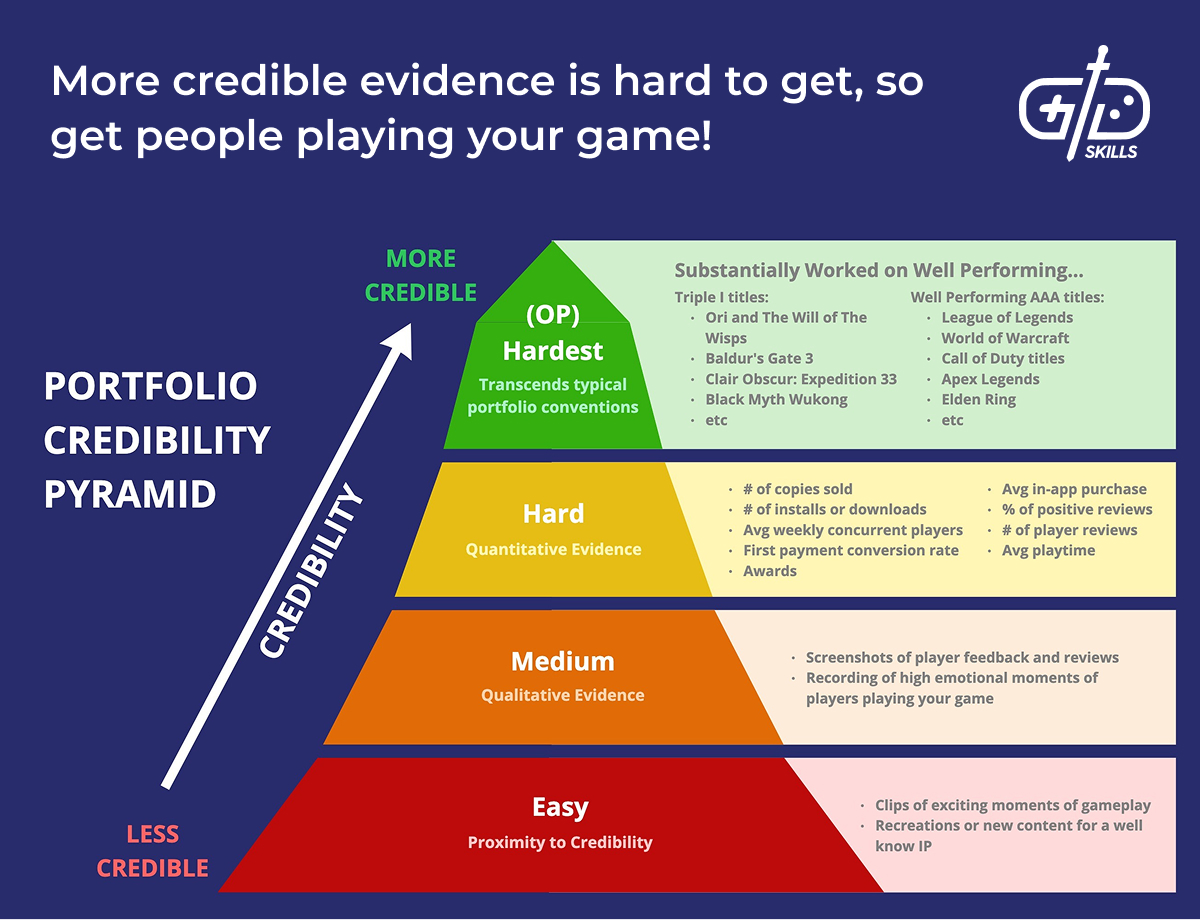

AAA experience speaks for itself. The job of a portfolio is to give the most credible evidence for the information on a resume. A resume is a series of assertions: the portfolio is the proof. Work on projects with big studios and popular games essentially speaks for itself. Designers don’t need an introduction to those games.

Examples of gameplay show credibility when there isn’t AAA experience on your resume. Visuals from the game serve three purposes: hooking the viewer into the portfolio, showing an ability to polish work, and showing that the skills on the resume translate into fun experiences. Starting a portfolio with a preview of the project from beginning to end makes the progress seem impressive. They’re prepared to read on knowing they’re going to find an answer to how a rough plan turned into a finished product. A systems designer doesn’t have the same luxury, but a preview of the results they got has a similar effect. The reader wants to know how they improved player retention by X% or achieved Y benchmark.

Live gameplay also shows you’re able to make fun, which is the real goal of a designer. The best gameplay includes examples of playtesters reacting: getting excited, just barely scoring a win, or having an intense moment of realization. Fun is hard to define, but like Potter Stewart the reader will know it when they see it. Sean Uslanian’s portfolio introduction shows footage of playtests and player responses: “Oh, that’s cool.” “I come down here, I get more vista: this is nice!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ptCKRjUrAwY

Our Funsmith Club discord server has regular live playtest sessions. The following video was put together from one such session, and it’s an effective way to show your project has the potential to create fun moments. Players are leaning forward in their seats, yelling, swearing, and celebrating their victories. While metrics and sales are the best proof of a designer’s skills, visual evidence like this is a close second.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jeTRtp_0ryg

6. Iterate like a live ops team

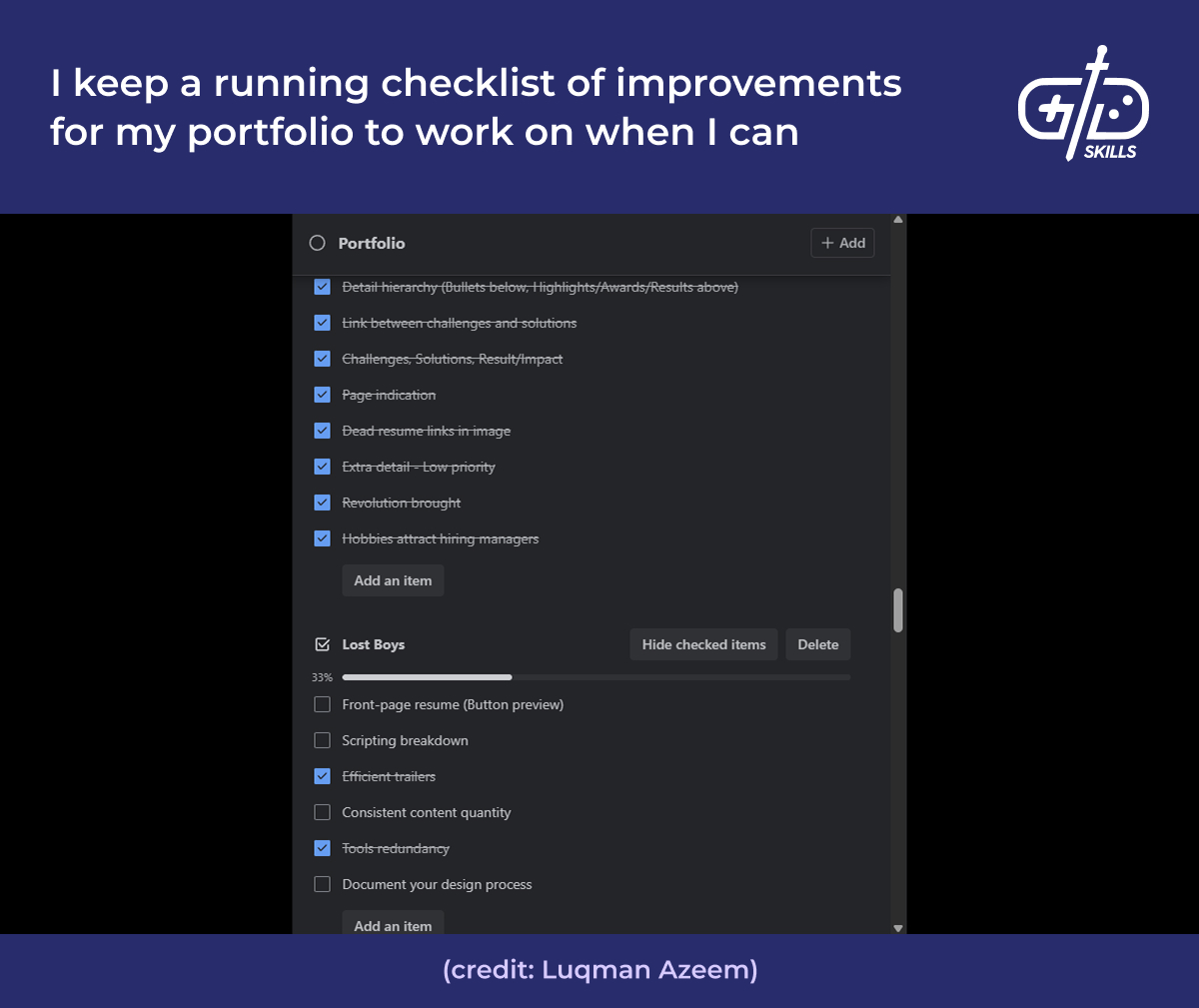

Iterate like a live ops team, which means iterating on the portfolio continuously. Update the portfolio continuously as you apply for jobs. Keeping a list of what to prioritize gets the portfolio to a workable state as fast as possible.

Keep a running checklist of what you intend to add to the portfolio. The portfolio isn’t ever going to be finished, so an organized list of what is essential and what is just nice to have keeps it focused. Apply to jobs, work on the most important items on the checklist, and then repeat. Don’t put off applying just because the portfolio is unfinished.

Document the process during each new project. Every new game is another opportunity to prepare a better example for the portfolio. In progress work is the best to showcase, so take screenshots of the work you’re doing, or diagrams you create. Keep the screenshots organized so you’re able to retrieve them later.

Replace older work with newer work as soon as it’s available. Publishing new pages on the portfolio immediately isn’t necessary if you’re worried about revealing information under NDA. Keeping the portfolio updated makes sure it reflects the most up to date skills. Dean Tate’s portfolio mentions his early work as a modder, but it isn’t emphasized like his later work.

7. Seek feedback for your portfolio

Seek feedback for your portfolio from professionals in the industry. Contacting designers you worked with on the projects is an effective way to get feedback and a reference. Online communities for game designers also have portfolio reviews for people who need to get their portfolio in front of fresh faces.

Experienced designers are the best source of feedback. Senior designers know what hiring managers look for, in such a niche field. Finding the right format for expressing your skills is difficult when there’s not a lot of help out there. The changes I noticed had the biggest effect on the number of interviews I got all came from experienced professionals. The disadvantage of approaching experienced devs is that their time is limited, and getting their feedback is rare.

Join a game dev Discord server to get in touch with a more accessible community. Our Funsmith Club server has regular portfolio reviews. There’s room for designers in and outside of our bootcamps to get feedback at any time on their work. Drop in anytime!

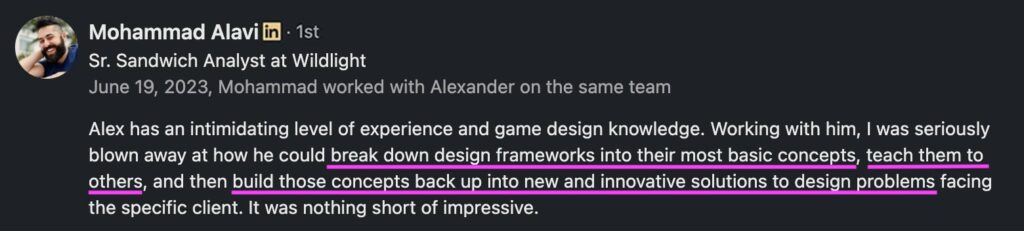

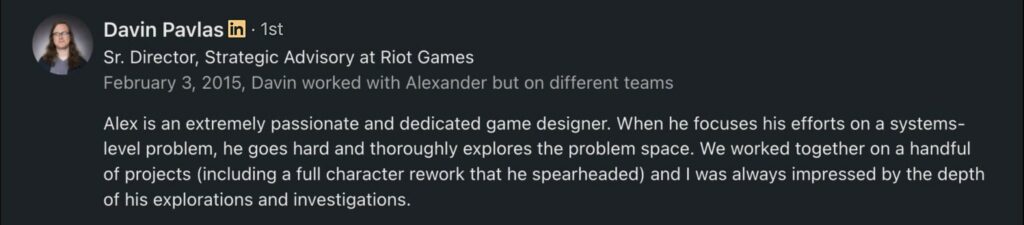

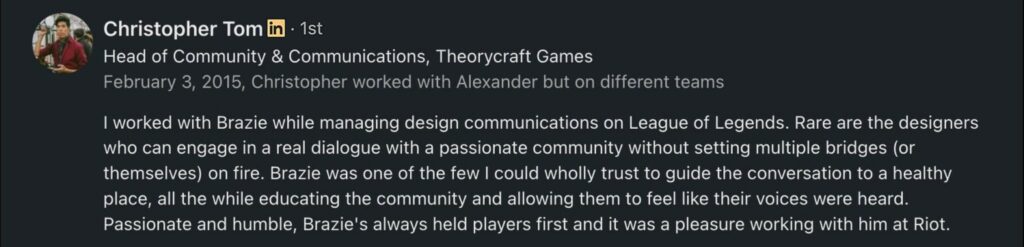

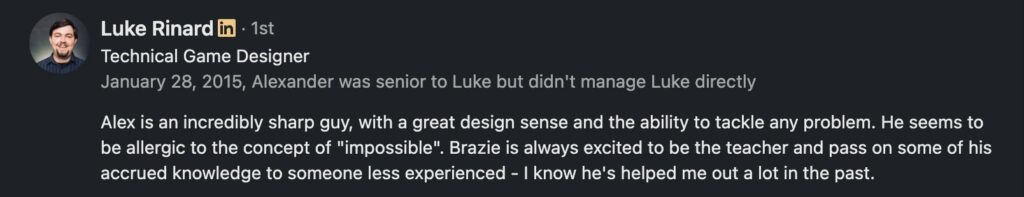

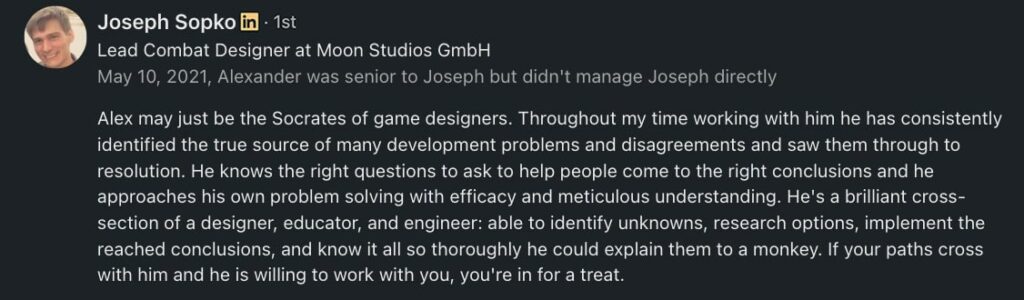

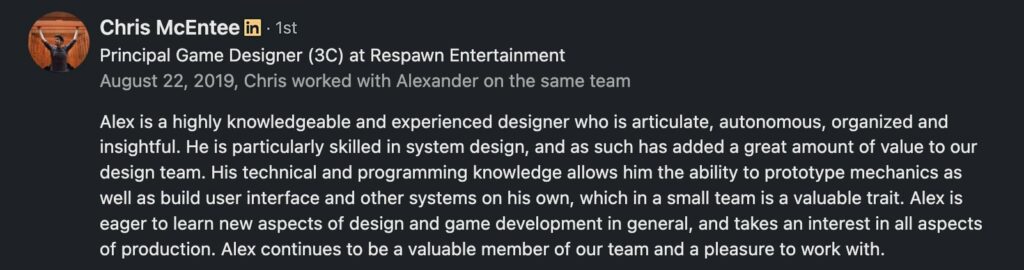

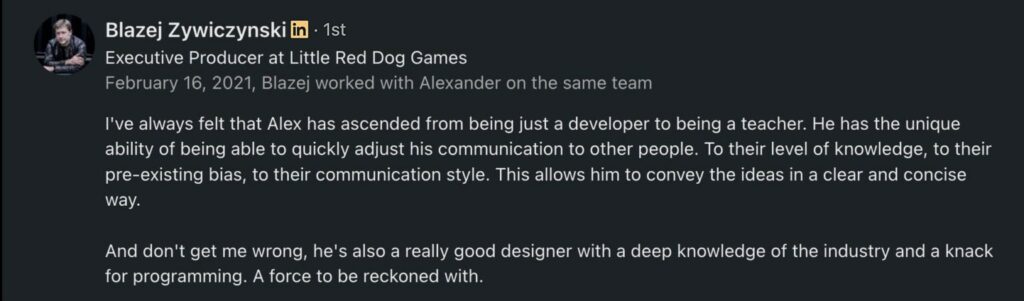

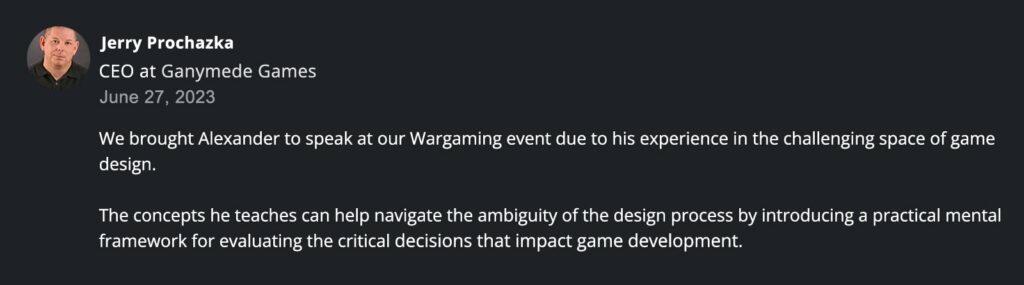

People you’ve already worked with are another avenue for feedback. Former co-workers are sometimes willing to write attestations to your work that make the portfolio even more effective at demonstrating your skills. Having co-workers that have your back and speak to your leadership show the strong communication skills employers are looking for.

Knowing when a portfolio is improving for the better is difficult. There is always feedback. Feedback past a certain point isn’t going to make the portfolio any more effective. They aren’t always the only difficulty behind getting a job either. Portfolios aren’t the only stumbling block either, especially if the odds are against you, like you’re in need of a visa. Under these circumstances, slow down when feedback starts to conflict with itself.

What are good examples of game design portfolios?

Good examples of game design portfolios are the websites by Larissa Mendes, Yuri Mainka, G. Falcon, and Nathalie Jankie, and David Burnham. The selection includes samples of work by gameplay designers, narrative designers, and level designers. Each one comes with an example from our GDS courses and from the industry at large.

Larissa Mendes built a narrative design project portfolio with our GDS template. The portfolio follows clear formatting. A reader interested in how she handles, say, storyboarding has an easy time finding it. The site has a navigation bar, headings, and she bolds key terms within paragraphs.

The portfolio demonstrates a diverse set of key skills: writing voice-over scripts, creating content research documents, and storyboarding key story sequences. Non-linear, branching story paths and localization are unique challenges in game design, and she clearly demonstrates both skills in her portfolio.

Yuri Mainka’s portfolio is an example of a narrative designer’s portfolio with a selection of projects, not just one detailed case study. A clear title at the top of the page makes clear to recruiters what position Mainka’s qualified for. Click on each project to get a direct link to the project, writing samples, and most importantly, the goals and contributions Yuri provided to the project. The page is worth visiting to look through the case studies in detail.

G. Falcon’s portfolio highlights her level design skills through an overview of her project from beginning to end. The level is a result of one of the workshops Nathan Kellman led here at GDS. The top of the portfolio gives a preview of the level at each stage of development, which directs the reader to read on and learn how the level got to its final form. The video at the top highlights each area as she discusses it, making the process easy to visualize.

G. Falcon shows an ability to iterate based on feedback and work with a team in addition to clear formatting. She includes video and written feedback from playtesters. The portfolio showcases the feedback alongside the changes she made to the level. The radical changes in the level’s final stage were a direct result of feedback. The encounter went from a flat plane to an area filled with scaffolding and cover that breaks sightlines.

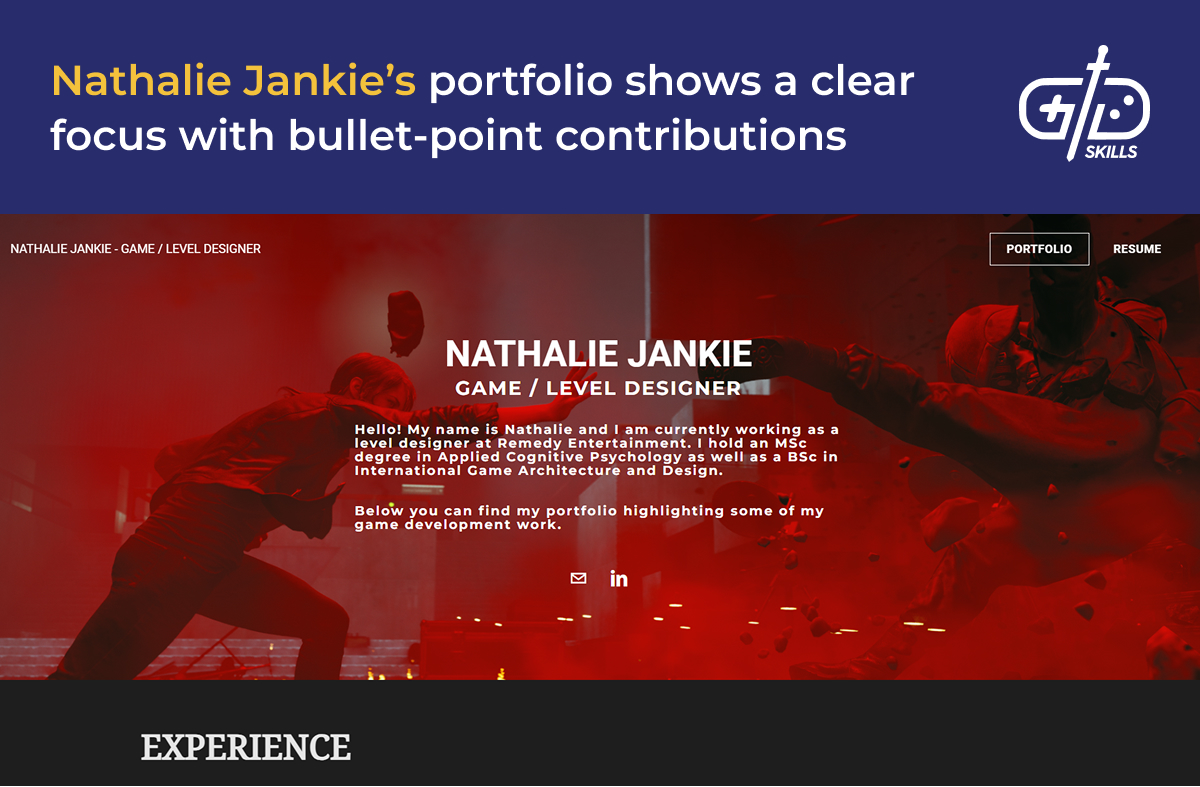

Nathalie Jankie is a level designer that demonstrates the role credibility plays in a portfolio. The most credible evidence is work on a popular title, and her work on Control speaks for itself. Her descriptions of her projects focus on general contributions and roles, not extensive deep dives. Nathalie Jankie lists her most important work first, leaving the student projects for further down in the portfolio.

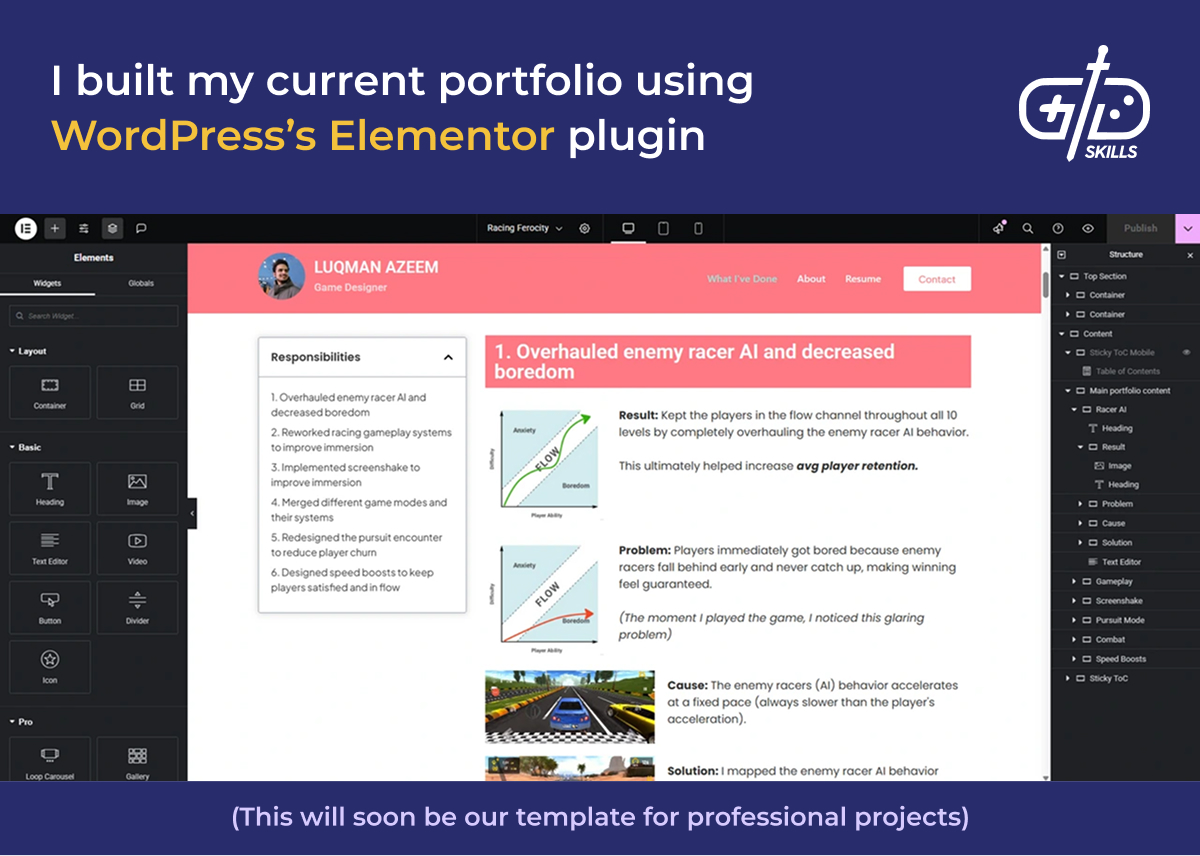

Gameplay design portfolios from our website show the properties of a clear, well-formatted game design showcase. David Burnham’s portfolio and my portfolio show what a gameplay or systems design portfolio with our template looks like. The page describing my work on Racing Ferocity and David Burnham’s page showcasing his work on Monkey Doo give detailed breakdowns. The responsibilities and contributions are clearly listed. A table of contents on the left side helps readers easily navigate the site. Each contribution isn’t just formatted well, but comes with extensive evidence for our work. Images, GIFs, and flowcharts show off the design process.

What are the common issues in a game design portfolio?

The common issues in a game design portfolio stem from not knowing what format to use. A portfolio is a coherent narrative that leads the viewer through proof of its creator’s skills. A portfolio that doesn’t have enough proof, isn’t clear, and doesn’t dive into the details isn’t going to be an effective tool.

A game design portfolio often runs into the following issues.

- Portfolio materials are under NDA

- Poor formatting that is hard to digest

- Unrelated visuals

- Not documenting and capturing visuals of the work during the design process

- Too shallow, doesn’t show design decisions nor process, which is essentially a glorified resume/CV

- Lack proof of work (visuals like images/GIFs/videos = proof)

Let’s start with the first item in the list, work under NDA. An essential project for the portfolio in some cases isn’t available for your portfolio. Build the portfolio page first and wait until release to publish. Creating the unpublished portfolio page still forces you to reflect on and present your contributions. Videos and GIFs of the final product are also perfectly acceptable once the game releases.

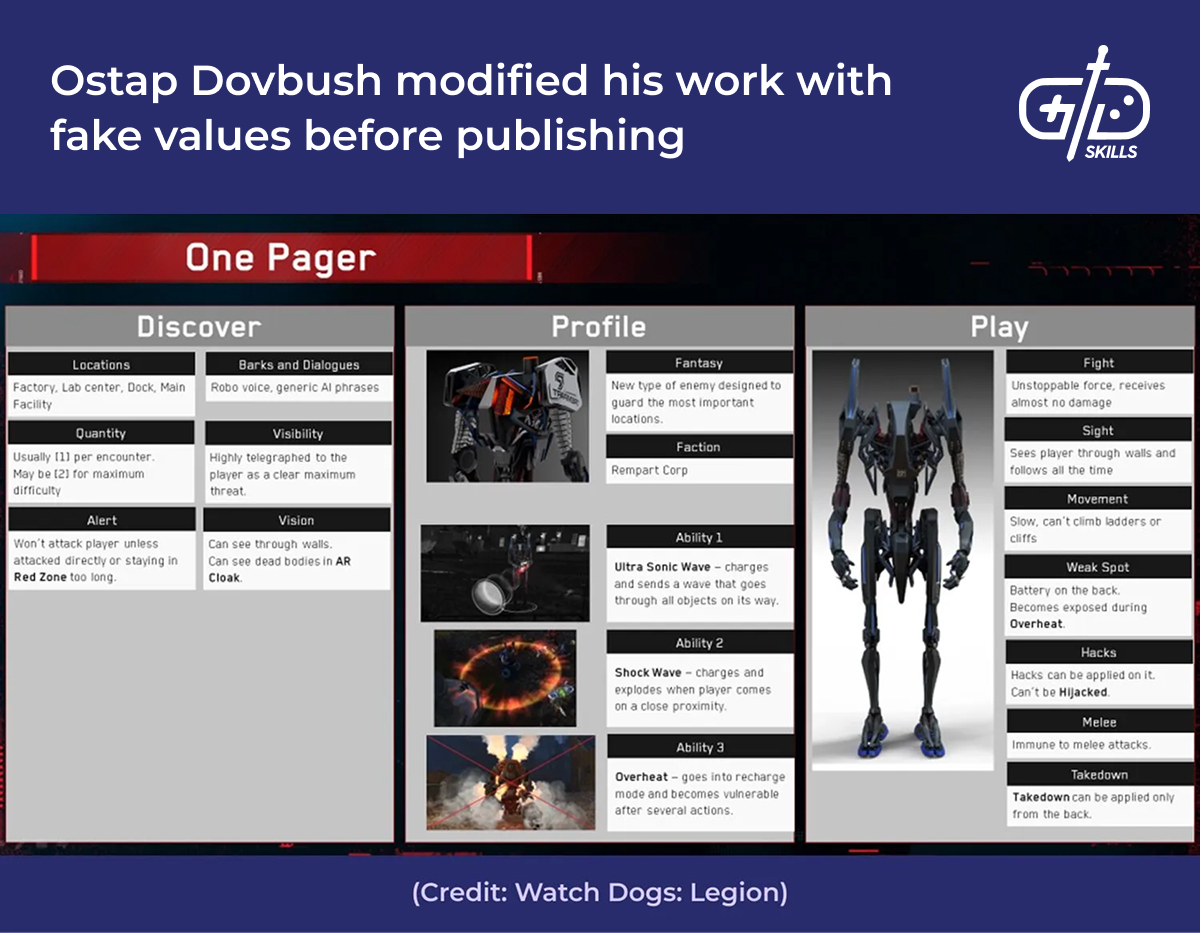

Screenshots of the editor, spreadsheets, and proprietary documents are a different matter. Contact your lead for specific guidance about what it’s possible to include in your portfolio. One option for including proprietary material is to modify it with fake data. Change up the numbers in the spreadsheet or editor so they don’t reflect the actual game. It could be an entirely new project that you rebuild your system in, with completely different assets.

Poor formatting is another issue with dire consequences but an easy fix. Headings and bullet points here and there makes a resume much easier to read. Going overboard is just as bad, though. A portfolio page filled with headings, bolded terms, italics, highlighting, and captions is just as intimidating as a wall of text.

Some of the formatting tools just mentioned draw readers’ attention more than others. Recruiters are going to pay attention first to headings and pictures, then bolded terms and body text. Make sure those headings and pictures communicate the most important information even if the reader didn’t see a word of the body. Great formatting like this isn’t as important as great content, but it’s much easier to achieve.

Visuals unrelated to the context are a common problem with new portfolios. Unrelated visuals don’t make efficient use of your portfolio’s precious space. A stylish portfolio filled with images is great, but it doesn’t do as much good as an uglier portfolio with only relevant visuals. They are the most important part for building your credibility as a designer. The images and videos show you’re able to document your work and deliver a product.

Several images make a portfolio pleasing to look at while still adding context. The following list describes visuals that make for a varied but clear portfolio.

- A video overview of the project at the top draws the reader in with something more digestible, one that relies on visuals and audio alone.

- An image gallery helps show step by step progress, or just present a lot of different images on one topic.

- A sliding bar for showing the same scene at different stages of development.

Failing to document the process during development is another key issue. The ideas and processes are fresh during development, but they get stale quickly. Keeping a journal or some kind of record makes it much easier to document challenges you overcame. Take screenshots and start building a portfolio page before you’re even done with the project to make sure there’s enough evidence of your work in there.

Another common issue is a portfolio that looks like a longer resume. A resume is too long when it runs into two issues. The first is that additional projects don’t add more context. Keep the portfolio focused to a list of the best, most representative work. The second is that the portfolio goes over every project in equal detail. David Shaver’s portfolio with a detailed breakdown of nearly every project works great for an experienced AAA designer. A new designer with such a long list is going to seem unfocused and have trouble communicating their strengths.

A similar issue is a lack of proof. Written context is crucial for a portfolio, but is only as credible as the supporting evidence. The portfolio is the primary source of credibility for a recruiter. Include images of the project at several stages. GIFs and videos show the gameplay directly to the reader, which doesn’t just boost credibility but clarity.

What is a good game design portfolio template?

A good game design portfolio template is the one available on our website. The WordPress templates are available to those who take our bootcamps, but read on for a quick look at the base template. There are tools available online for getting a starter portfolio going as well, if you want to practice first. WordPress, Webflow, Notion, and ArtStation are common options for starting yourself.

Game Design Skills provides a template via two of our bootcamps currently. The narrative design and level design bootcamps teach skills for building a project and turning them into portfolio pieces. The Narrative Bootcamp most recently was led by Kelly Bender, who has worked on over 30 published games. Nathan Kellman, a level designer who has worked on Diablo IV, taught our summer Level Design Bootcamp. Join up with our bootcamps to get help with building a portfolio tooled to your discipline!

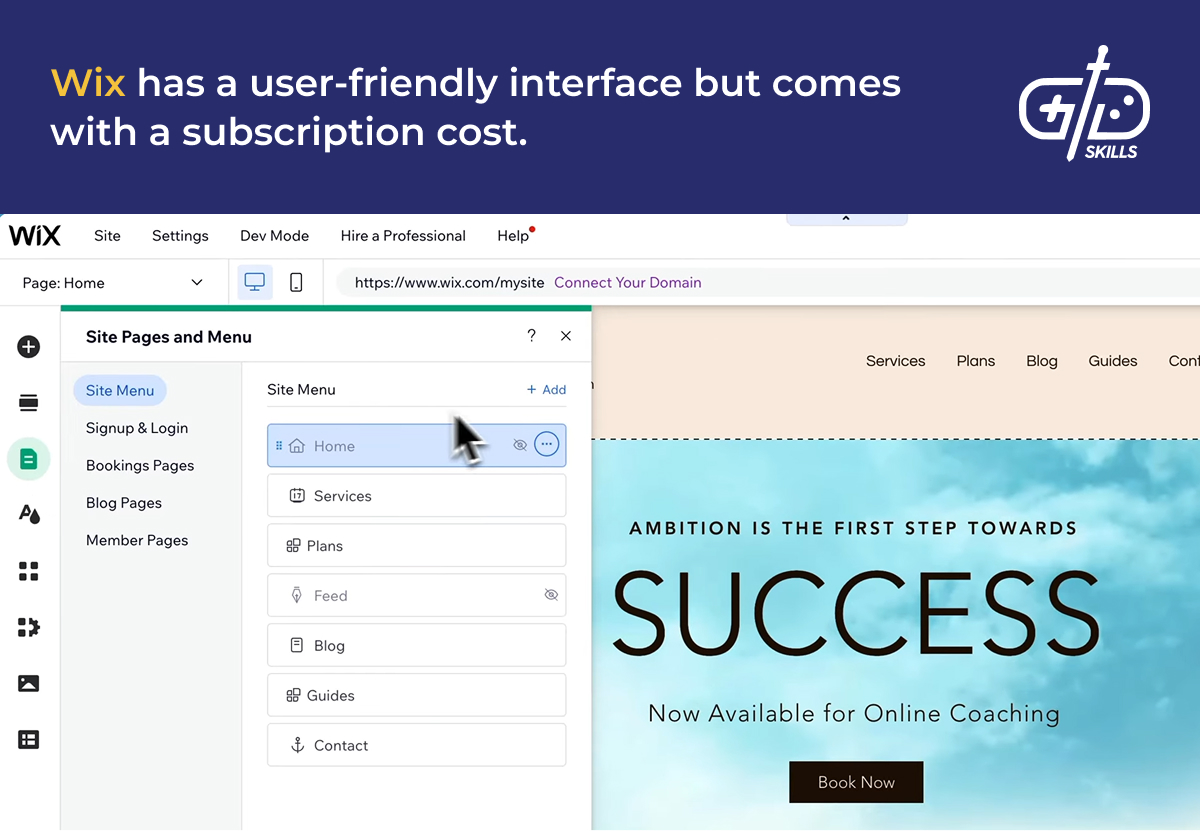

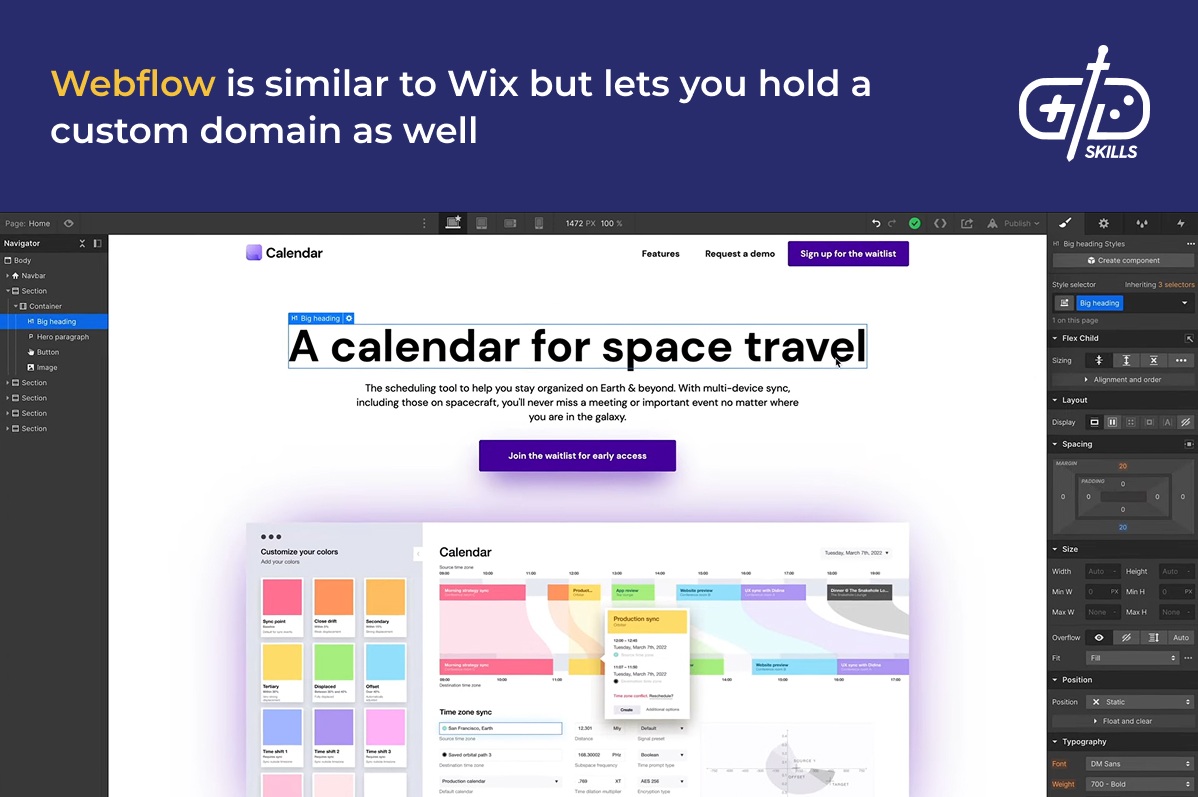

Online tools are another option for giving a portfolio a try on your own. No matter the tool, there’s a price for hosting a website, so keep that additional cost in mind. WordPress is a tried and true tool, but comes with a learning curve. Wix, Webflow, and Notion are other popular options for their ease of use. Artstation is built to show off art, so it’s another suitable place to start for building a design portfolio.

WordPress is the option I’ve used personally. WordPress lets the user build full websites, giving them a lot of control over the presentation of their work. The Elementor plugin we use is free, though pro features are locked behind a paywall. Buying a domain and hosting it are separate processes for WordPress, though, and don’t come built in like the other solutions. Hostinger and Kinsta are hosting services that have performed well for our portfolios in the past.

Wix works similarly to Elementor. Wix has a drag and drop interface for building full websites that is easier to use than the base WordPress tools. The editing and hosting service are packaged together with Wix, but the package comes at a fee.

Webflow is a similar web creation tool with the advantage that you get a custom domain. The base experience is much more user friendly than WordPress out of the gate. The service also handles software updates and maintenance. The downside is that the cost of webflow is higher than it is for WordPress and comparable to Wix for a single user.

Notion isn’t a web design site but is perfectly capable of providing a game design template. Notion is a general purpose tool: it’s useful for note taking, project management, and wikis. There isn’t a limit to what you use for the portfolio. I’ve seen seasoned professionals use Google Slides as well. Notion is an easier way to combine images and text without dealing with web hosting.

I started with ArtStation at the start of my career, even. ArtStation is a site built for artists, not designers. It’s a forum for working artists to post their work online. ArtStation has the lowest level of flexibility, but the simple format works well for beginner designers. Game design wasn’t as big a discipline when I started in Pakistan, so I began with an ArtStation page as my first portfolio. Just having a portfolio at all was enough to set me apart, as a candidate.

What should I include in a game design portfolio for college or university?

You shouldn’t include anything different in a game design portfolio for college, since they aren’t required for admission. Students finishing up college, on the other hand, are a different story. They’re entering the job market before they’ve even finished their last semester, so it’s already time to think about application materials. A hiring manager is going to consider the experience more crucial than the degree, so have a starter portfolio ready to go. Stick to similar principles as the other portfolios mentioned already.

Coming out of school with project experience is the ideal. Going through a design process with a team and playtesters shows an ability not just to implement designs but polish them. Getting feedback on the project from a teacher is another credibility boost to the portfolio, if the teacher has worked in the industry.

Students don’t always come away with group work on their resume, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have a chance. Student projects and even unfinished work that shows off your skills works for a student designer looking for their first job. Break down the projects in detail if you don’t have a lot of them, and look back to our templates and case studies for examples of what a breakdown looks like. Many smaller projects are worthwhile to include in the portfolio if you don’t have any large completed ones, but keep the portfolio organized. Multiple projects that show the same skill clutter it up.

Having the following items and skills coming out of a program makes for a solid head start.

- Resume

- LinkedIn profile

- Portfolio (starter portfolio with one or a few projects is fine)

- Team project experience

- Playtests and feedback on your projects

- Experience with a game engine/coding

6 Responses

Thank you so much for this this post on game design portfolio, …it came right on time!

Huge Xbox head here, who also doubles as a game programmer …seems like design portfolios are much more complicatd than game scripting portfolios.

I’m currently do web design and IOS app design looking to venture into game design. These are some great tips, I especially appreciate the portfolio website examples you shared.

It’s so good that experienced people share and give advices to motivated noobs 😛 Thank you, Alex! Please keep up the good mission ^_^

Trying!

Excellent content! Very informative.