What is the three-act structure?

All stories must have a clear Beginning, Middle, and Ending, and the three-act structure is the easiest storytelling tool to separate your ideas into these three parts.

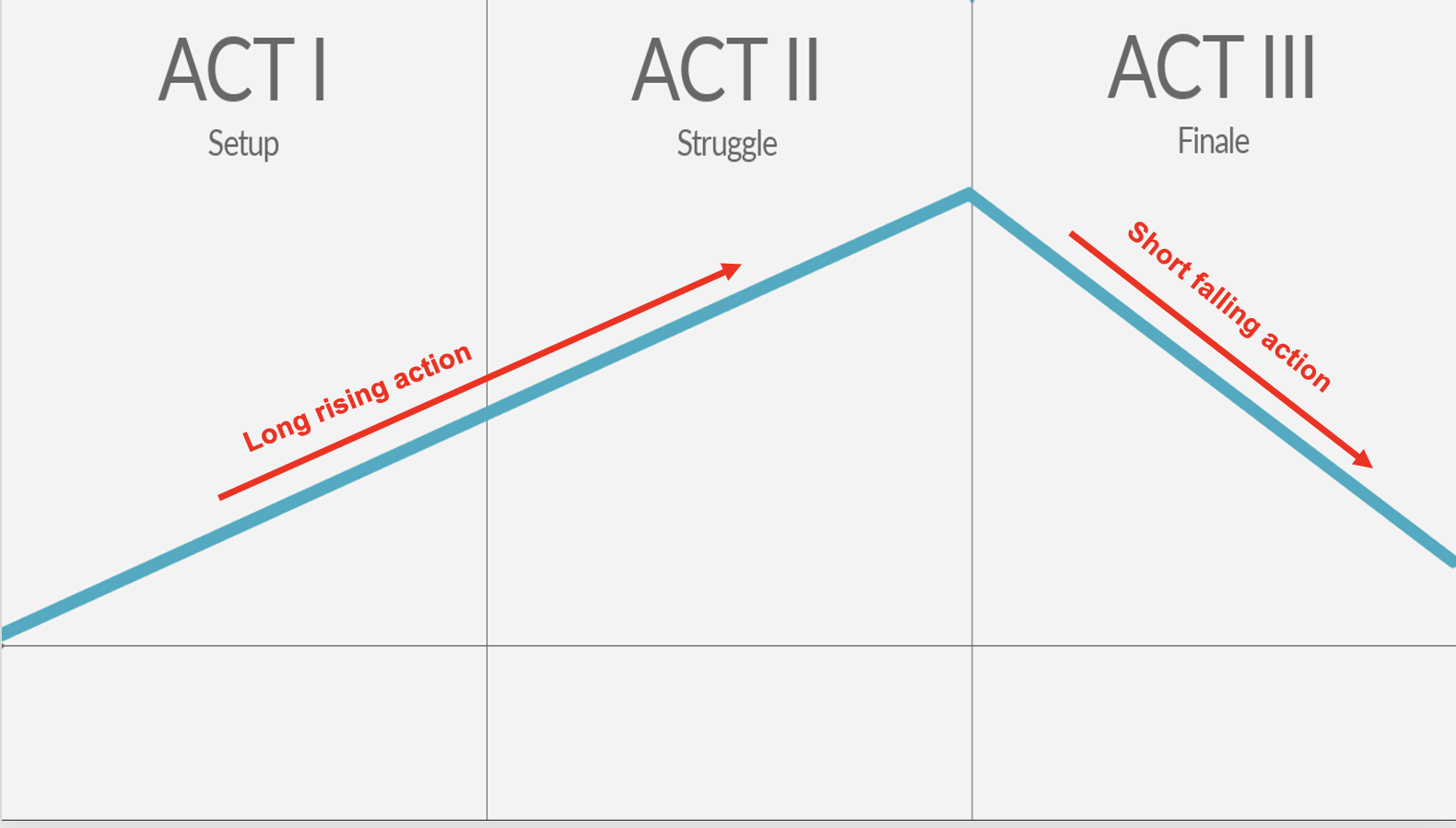

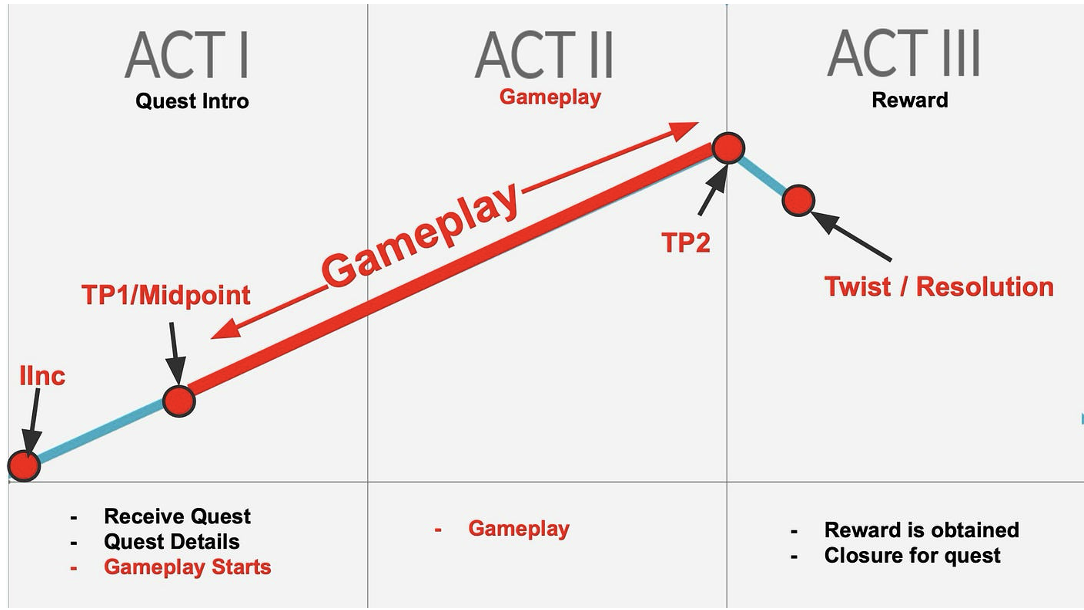

The three-act structure is a storytelling tool coined by screenwriter Syd Field in his book, Screenplay. His thesis is that most popular stories can reliably be broken down into the three parts outlined in this image:

The specifics of every story are different, but the three-act structure provides a framework that helps writers analyze others’ work and check that their own adheres to the most important audience expectations.

Generally, people want novel experiences packaged in familiar formats. Humans expect their overarching narratives to be presented in three distinct blocks.

The quasi-mystical numerological reasons for the supremacy of the number three across various cultures, religions, and art forms are best explored elsewhere. We’re here for the application to games.

The key takeaway:

Humans are programmed to expect narratives in three parts.

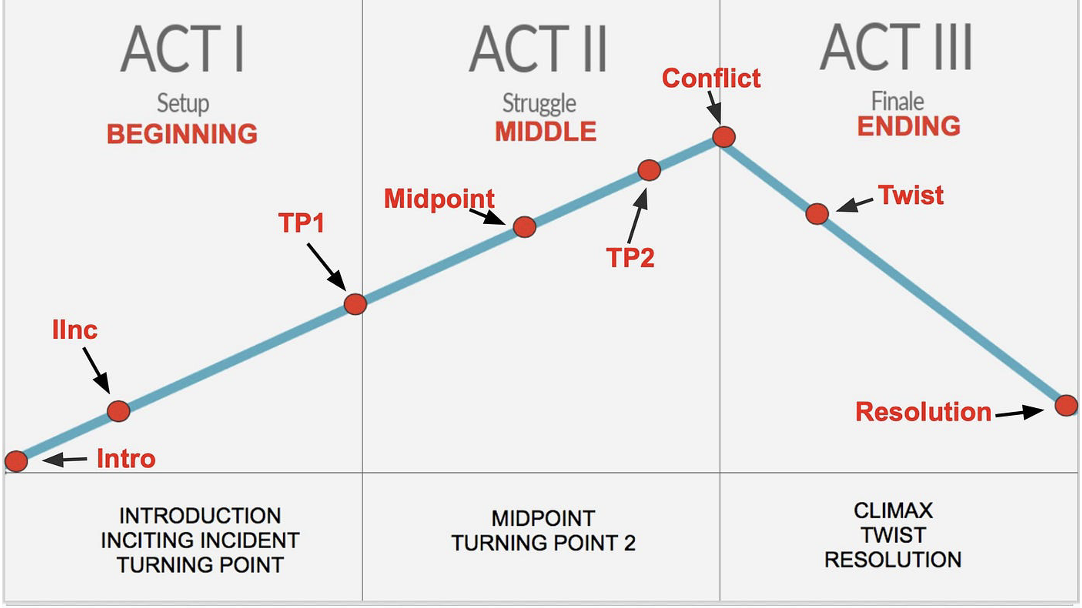

Let’s use the movie Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone to break down the three-act structure and its various plot points.

Act 1: Beginning (Setup)

- Intro: Where the protagonist is introduced in their everyday life. (Ex: Harry Potter living in his aunt and uncle’s house)

- Inciting Incident (IInc): This is where something happens to affect that “normal” life. (Ex: Harry Potter gets the letters from Hogwarts)

- Turning Point 1 (TP1): This is where we meet the world behind the curtain, where the normal world becomes mundane. (Ex: Harry begins to see the magical world that is Hogwarts)

*Note: This is also where secondary characters are introduced, which will deeply impact the protagonist’s journey. (Ex: Ron and Hermione)

Act 2: Middle (The Struggle)

- Midpoint: This is the point of no return for the protagonist; they have learned or seen too much and can’t return to their normal life anymore. (Ex: Harry learns that Voldemort killed his parents).

- Turning Point 2 (TP2): The second act culminates with Turning Point 2, where the hero’s attempt to thwart the antagonist fails and all seems lost. (Ex: Harry is attacked by Voldemort and almost dies.)

Act 3: Ending (Finale)

The Third Act is all about the final battle and its outcome. Defeated, half dead the hero learns their biggest lesson from their worst failure.

- Conflict: When the antagonist seems to win and the protagonist seems to lose. (Ex: Harry has lots of obstacles (library)/puzzles and conflicts to deal with at the start of the third act, like Snape/Quirrell/Voldemort.)

- Twist: The twist is just that: something you didn’t see coming. Now, I’d like to point out that this doesn’t have to be a shock or a WTF moment—it can be something as simple as the hero seeing the truth, coming up with a new strategy, realizing who the killer is, finding the mega weapon, etc…The twist is what enables them to turn a loss into a win. *Note: Not all stories have to have a twist, but if you do have one, it should appear here.

- Resolution: The protagonists return to their world but are forever changed in the resolution.

The following image plots these complexities along the three-part timeline. Take a moment to apply its framework to your favorite movie:

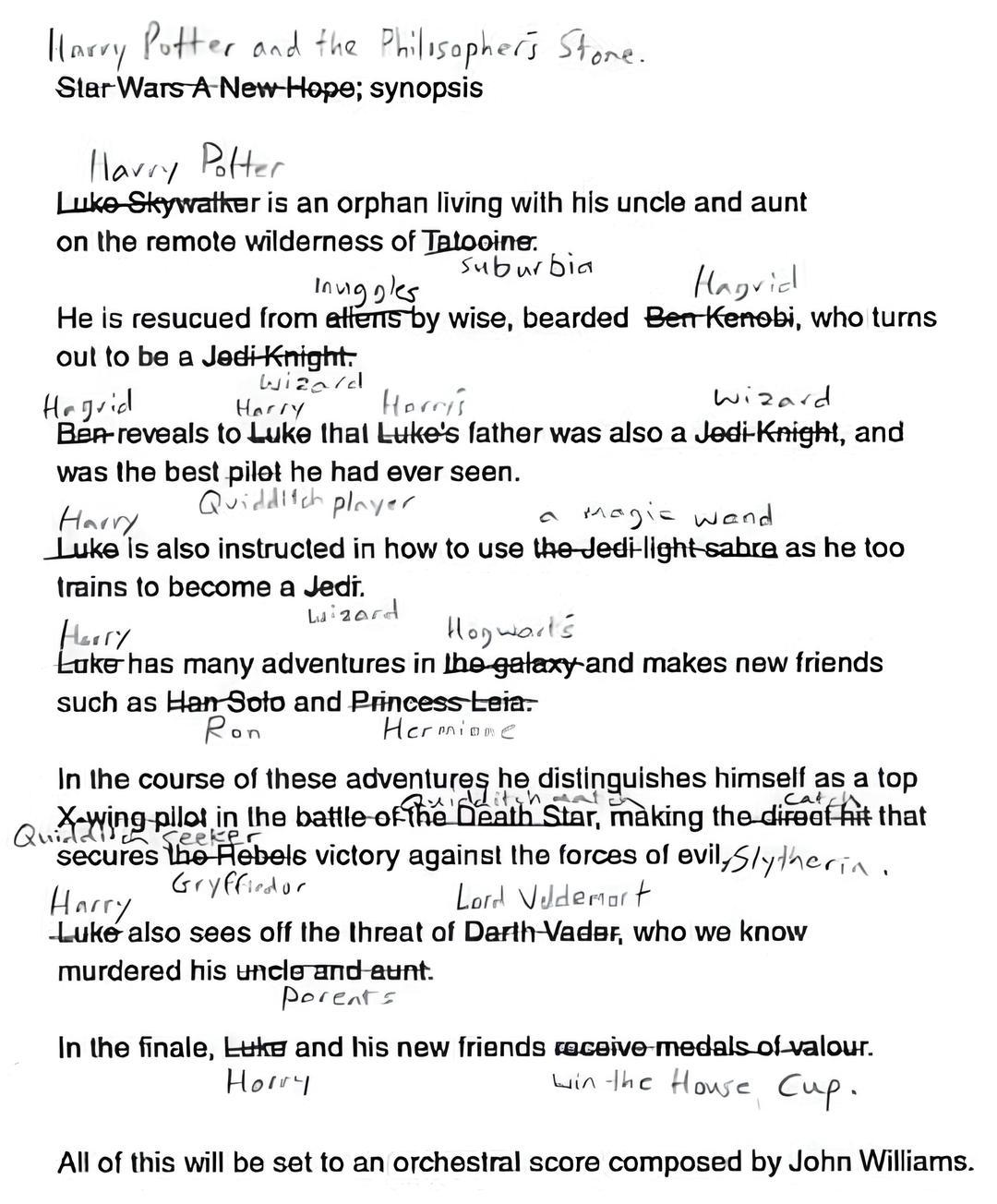

While the above analysis is all specific to Harry Potter, the extent to which the specifics are interchangeable is remarkable.

I’m not out to destroy anyone’s childhood here but there are striking similarities across most epic tales (an example is pictured below.) This was originally shared by the writer and broadcaster Stephen Fry.

While this analysis can be interpreted as sucking the magic out of fiction, writers must understand how the sausage is made—however unpleasant their time at the meat grinder is.

Once every generation (if we’re lucky) there’s a writer who both breaks the mold and has the talent to appeal to a mass audience. For the rest of us, let thousands of years of storytelling tradition do the heavy lifting:

Storytelling masters deliver their tales in three distinct cuts.

So, does the three-act structure work in video games?

The short answer is…kind of.

Let me explain.

Movies and TV shows are very select highlight reels of their protagonists’ lives—every scene must develop a character or progress the plot. The same rule applies to novels. Anything that doesn’t develop a character, relationship, or the overarching plot is typically cut.

Video games are also a type of highlight reel of the main character’s life. However, because we have agency, direct control over the action, and a stake in the outcome—our perceptions of what constitutes a highlight change.

Think about it—how many people would continue to watch John Wick movies (referenced below) if Keanu spent forty-five minutes (real-time) modding his weapons the way a Fallout player might? We need more immediate dog revenge, cinematically speaking.

It’s not that the character in John Wick doesn’t service his weapons and install mods. It’s just that watching it in real-time isn’t compelling in cinema.

The montage technique exists for a reason. When filmmakers feature events in a real-time sequence, we find it jarring.

For example, Rowdy Roddy Piper’s famous (or infamous) incredibly long fight scene in John Carpenter’s 1988 They Live (lovingly recreated below) seems so incongruous because of our expectations for the medium.

The scene clocks in around six minutes but seems like an eternity in context (a good or bad thing, depending on your enthusiasm for pro wrestling). It simply doesn’t fit the cadence we’ve come to expect from a standard Hollywood three-act movie:

However, context is important. The same runtime of six minutes is a slightly shorter than average round of combat in Dungeons & Dragons or about two or three matches of Street Fighter 2.

In the cases of D&D and Street Fighter, the time doesn’t drag because of our expectations. Similarly, when we play games (especially open-world games, RTS, RPGs, etc), our agency over the action and investment in the ultimate outcome shifts our perception of time.

In these games, we can accept activities like collecting herbs, brewing potions, modding weapons, mining, crafting, and building that might seem tedious in other media or genres.

Admittedly, there are always cases where developers may overestimate how much real-world tedium is enlivened by gamification.

Many considered this six-minute box-moving shift down at the docks with Delin in Shenmue excessive:

(Searching for this video only reminded me of how immersive and revolutionary that game felt for its time, but it’s an infamous example!)

Because we’re active participants in games and often play them over weeks or months instead of a single sitting, they don’t need to set up and resolve all their conflicts at once.

A movie’s three-act structure may unfold over a single ninety-minute session. (Or longer, nowadays!)

While a game’s narrative design may have a similar overarching plot structure as a movie, the nature of the medium requires this narrative to stretch throughout the entire game.

However, a similar three-part structure is also applied to smaller chunks of gameplay so that players are taken on a recognizable journey during each play session.

Side quests are the best way to illustrate the three-act structure writing tool in video games:

Act 1 (Beginning): Introduction

- Inciting Incident: The inciting incident in video games is when you tap or press a button to interact with an NPC quest giver.

- Turning Point 1: This is where the player learns more details about the quest (what you must do; find/kill/return/steal/etc. and where it is).

- Mid Point: This is the point of no return (actually you can return if you want), the Quest Accept stage. *Note: Players can also decline the quest.

For example (warning—minor spoilers for a decade-old game!), in The Witcher 3’s side quest Carnal Sins, Act 1 begins with a messenger running into the Rosemary and Thyme with a message to say Dandelion’s friend, the poet Priscilla, has been attacked and lies ill at the hospital. This is the inciting incident.

The first turning point arrives in the hospital when Doctor von Gratz tells you Priscilla isn’t the first victim. He asks you to follow him to the morgue to learn more. Unsurprisingly, following the doctor leads to exploration and combat—gameplay begins.

Act 2 (Middle): Gameplay

- This is where 80% of the story comes in. *Note: This part of the story comes from the level designers, game designers, and game artists (but the narrative designer/game writer is part of those conversations as well).

- This is where the CONFLICT comes in as well. *Note: Conflict doesn’t have to be fighting; it can be pressure from the clock, harder obstacles, tougher puzzles, etc.

In the case of Carnal Sins, Act 2 begins when you arrive at the morgue and examine the body. After some investigative gameplay, you’re interrupted by other interested parties. There’s even a clue to the mystery in this interaction.

The player is then presented with three leads they can investigate in any order. Learning the information from each is a mix of bribery, manipulation (using Axii in The Witcher’s universe), and the Batman: Arkham Asylum-inspired Witcher-sense investigation. The bulk of the gameplay is here.

Eventually, the player finds a note naming the next victim. Geralt is compelled to rush to the scene.

Act 3 (Ending): Climax and reward

- Turning Point 2 occurs here, at the climax of the conflict, and when the player returns for the reward. *Note: The climax of the gameplay can lead to a secondary conflict.

- Twist: If your story has a twist it occurs here at the end.

The second turning point in Carnal Sins hits when on arriving at the scene, the player realizes they’re too late but the killer is still present. In a fun twist, the guards mistake the player for the killer as you flee.

Once this situation is resolved, we learn the killer’s next victim. This leads the player to the climactic battle, but not before the twist revealing the killer is someone we’ve encountered already on the quest—a twist!

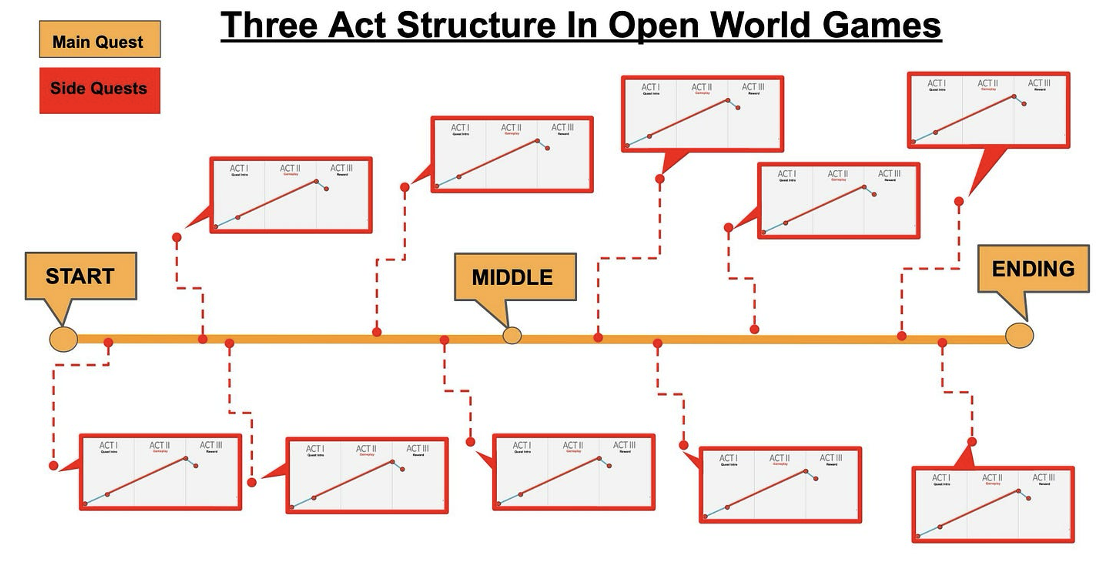

The three-act structure in the main quest storyline

The image below shows how the three-act structure could work throughout the main quest storyline and the side quests.

Note: Most AAA games are broken down into five acts rather than three. There’s still a discernible beginning, middle, and end, but each section has its own beginning, middle, and ending, broken down into “levels”, “mini-boss fights”, and “boss fights”.

Each level (or epic quest line) has a beginning, middle, and ending, but so does each side quest within each level, and every character story quest, daily quest, monthly quest, etc.

The challenge of effective writing is in making each quest contribute meaningfully to the whole, creating short-term payoffs that contribute to a broader narrative. (Just like how a singular comic book story has its own beginning, middle, and ending, but becomes part of a larger beginning, middle, and ending when compiled into a graphic novel.)

Open-world games often simply have too much content for a simple three-act narrative to work.

As this image shows, they typically contain faction and companion quests that can run in tandem with the main plot until the player reaches a point of no return in the narrative:

These sidequest lines follow the three-act structure, both at the macro level—creating a rising sense of urgency with payoffs throughout the quest chain—and at the micro level, making sure each mission follows a familiar three-part arc.

The Witcher 3’s main quest provides a good example: Tracking down Ciri in Act 1 creates a compelling reason to explore three locations, each containing its own narrative beginning, middle, and end:

Act I

- In Ciri’s Footsteps – Velen

- In Ciri’s Footsteps – Novigrad

- In Ciri’s Footsteps – Skellige

Act II

- Uma’s Curse

Act III

- Wild Hunt

Acts 2 and 3 of The Wild Hunt are relatively lean, containing a single quest chain each for a total of five acts.

Of course, the beauty of the open-world experience is that some players’ time in the Pontar Valley is better summed up by this meme:

Another great example is Genshin Impact. In this case, the amount of content the game contains (and its audience demands) necessitates more than a single three-part structure can accommodate.

Genshin Impact contains:

- World Quests

- Region Quests (set within a specific region in the world)

- Story Quests (within the region)

- Commission Quests (themed within the region)

- NPC Quests (side quests) set within any region, town, or random area.

All of these are told in the three-act structure, but connected to a much larger storyline (a five-act one, in this case).

How to apply the three-act structure in games

TV series and video games share some narrative properties.

Both need to think about narrative structure across two vectors—how do we take the audience on a journey tonight and how do we take the audience on a journey over the coming weeks and months?

Great writing breaks rules when necessary, but consider the following as guiding principles that typically work in narrative-driven games for both individual missions and overarching quests:

Applying Act 1

Start with interaction: Because games are fundamentally an interactive medium, they don’t have as much time to play with prologues and first acts.

Think about it—how many games start you out in the thick of the action, teaching you the rudimentary controls as you deal with a minor crisis minutes into the game? There’s a reason for this.

Players hate being railroaded with unskippable cutscenes or sequences where their control is relinquished. (I know dyed-in-the-wool gamers who have never played Skyrim (referenced below) because of its fifteen-minute unskippable introduction.)

Start with action is a guiding principle for most genre fiction—it goes doubly so for a medium defined by interactivity.

Note: Some refine the “start with action” tip further to “hook the reader (or player) early”.

The hook could be action-based combat design, but it also could be puzzle-solving, resource management, or relationship development—the point is to write a reason for players to immediately engage with the game’s most compelling aspect.

Time for introductions: No matter the medium, the first act is the time to introduce the setting, conflict, and primary characters; it’s the main worldbuilding phase. (Assembling the team can stretch into Act 2 in team-based RPGs.)

After the first act, the player should understand the primary question that underpins the narrative:

- Can Geralt find Ciri and defeat the Wild Hunt?

- Can Link save Zelda and defeat Ganon?

- Can Shepard defeat Saren and save the Citadel?

- Can I get that goat to fly across four lanes of freeway?

(OK—maybe not the last one…)

Players should also become familiar with their primary gameplay options in Act 1. Refinement, modding, and personalization can all come in the second act, but the basics should be familiar by the end of Act 1.

Applying Act 2

Temperature rising: Act 2 is often where the bulk of the gameplay takes place, both within a single mission and across a main questline. This is where the challenge starts to ratchet up and the skills players have learned are tested.

The beginning of Act 2 often contains an “oh—this problem is bigger than we’d initially realized” moment.

You can think of countless examples where Act 1 culminates with the heroes dealing with what they believe is the problem. Once this issue is dealt with, it usually reveals a deeper, darker, more intense obstacle underneath.

An example is the 1979 classic, Alien (pictured below). While this case is specific to that movie, you can come up with countless other examples.

In this scene, the alien face-hugger has detached from Kane’s face, and the crew (and the audience) are lulled into a false sense of security. Their guard is down and everyone is enjoying a last meal before hypersleep—the perfect time to make them realize the adventure is only beginning!

Expand and compound: The weapons, characters, and conflicts discovered in Act 1 will get stale unless they develop.

Your connection to characters should deepen through shared experiences and dialogue. In CRPGs and squad-based games, you often continue to recruit party members well into Act 2, learning their backstories and motivations as you do.

Your sense of ownership over equipment and abilities should also increase as you modify and specialize. Even the main conflict should get its hooks deeper into you during this act as you explore how it affects the inhabitants of the game world.

Video games reach full speed in Act 2, both in terms of their gameplay design and narrative. The writing must ensure the stakes increase alongside the difficulty curve, working on the player’s emotions as the gameplay does on their reward system.

Applying Act 3

Point of no return: Act 3 begins when the player has assembled the team, mastered their skills, and refined their weapons and armor. (Or pumped everything into Charisma and lied, cheated, and bribed their way through.)

Great writing makes this delineation between acts clear and narratively coherent. To use the Mass Effect example, once Soveirgn is on the way to the Citadel and the Geth are on the station—it’s go time. The writing doesn’t allow for any other options.

Skill test: In many games, the big player skill test is a climactic battle with a big bad boss. Different genres use different tests, but the principle remains the same:

Use what you’ve learned at the upper limit of your skill threshold.

How satisfying this test feels comes down to both gameplay and writing. Think about it—when we watch combat sports (or any sports), the exact same content can be thrilling or dull depending on how much we’re emotionally invested.

When two athletes have a legitimate dispute that the audience understands, their contest is elevated beyond the punches, kicks, points, or goals.

Writers should view game narratives in a similar light—when the player gets to the big skill test in Act 3, has the writing done enough to…

A. Turn it into Ali vs Foreman 1 for all the marbles?

–or-

B. Does a lackluster narrative make it feel more like watching Jake Paul beat up retired Uber drivers half his size?

Here are 2 ways to get better at applying three-act structure in games

1. If you aim to get into professional game writing and narrative design:

Here is the 13-week live project-focused game writing bootcamp I intentionally designed for narrative designers and game writers aiming to get hired or junior professionals looking to upskill.

In this bootcamp, I’ll personally guide you to create industry-level, portfolio-ready projects using proven concepts and frameworks, including those covered in this guide.

As a member, you’ll also get

- Examples and demonstrations from AAA, AA, and mobile games I’ve shipped

- 7 guest instructors from various disciplines to share how they collaborate with game writers in real-world settings

- 1 adjunct instructor with AAA narrative design leadership experience to provide additional guidance

- A marketing specialist with 15 years of expertise to help turn your projects into a standout portfolio piece that gets interviews

- Small group to ensure focused, personalized attention for every participant

- Members-only free hosting, personalized subdomains, and proven templates to showcase your portfolio and retain the right attention

You can view the full bootcamp curriculum, instructors, and more details here.

2. If you’re just dabbling as a hobby:

In this case, you don’t need the bootcamp. Instead, the most practical way to learn about the three-act structure is to remain aware of it while consuming media.

When a story works for you, ask why. When you feel a particularly strong motivation to complete a quest, ask why.

Looking at media we love through the lens of the three-act structure teaches us the key components of good stories, and where they are best placed in a narrative.

Likewise, when a piece of fiction doesn’t work for you, investigate it:

- Has it adhered to the structure we come to expect from the particular medium?

- Has it set the audience up for the next act? Why/why not?

More three-act structure resources

- Syd Field’s Screenplay remains one of the most referenced books when it comes to writing for the three-act structure. A revised version is still in print, but there are also thousands of secondhand copies out there for peanuts.

- Joseph Campbell’s Hero With A Thousand Faces uses humanities myths and legends to distill a framework that exists within every epic tale. It’s particularly useful for video game writers given the medium’s typically epic scale.

- This video essay by writer K.M. Weiland explains the three-part structure in context in.